-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 92466

AGENCY:

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is finalizing federal Clean Water Act (CWA) water quality standards (WQS) for certain waters under the state of Maine's jurisdiction, including human health criteria (HHC) to protect the sustenance fishing designated use in waters in Indian lands and in waters subject to sustenance fishing rights under the Maine Implementing Act (MIA). EPA is promulgating these WQS to address various disapprovals of Maine's standards that EPA issued in February, March, and June 2015, and to address the Administrator's determination that Maine's HHC are not adequate to protect the designated use of sustenance fishing for certain waters.

DATES:

This final rule is effective on January 18, 2017. The incorporation by reference of certain publications listed in the rule is approved by the Director of the Federal Register as of January 18, 2017.

ADDRESSES:

EPA has established a docket for this action under Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2015-0804. All documents in the docket are listed on the http://www.regulations.gov Web site. Although listed in the index, some information is not publicly available, e.g., CBI or other information whose disclosure is restricted by statute. Certain other material, such as copyrighted material, is not placed on the Internet and will be publicly available only in hard copy form. Publicly available docket materials are available electronically through http://www.regulations.gov.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Jennifer Brundage, Office of Water, Standards and Health Protection Division (4305T), Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20460; telephone number: (202) 566-1265; email address: Brundage.jennifer@epa.gov.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

This final rule is organized as follows:

I. General Information

A. Does this action apply to me?

B. How did EPA develop this final rule?

II. Background and Summary

A. Statutory and Regulatory Background

B. Description of Final Rule

III. Summary of Major Comments Received and EPA's Response

A. Overview of Comments

B. Maine Indian Settlement Acts

C. Sustenance Fishing Designated Use

D. Human Health Criteria for Toxics for Waters in Indian Lands

E. Other Water Quality Standards

IV. Economic Analysis

A. Identifying Affected Entities

B. Method for Estimated Costs

C. Results

V. Statutory and Executive Order Reviews

A. Executive Order 12866 (Regulatory Planning and Review) and Executive Order 13563 (Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review)

B. Paperwork Reduction Act

C. Regulatory Flexibility Act

D. Unfunded Mandates Reform Act

F. Executive Order 13175 (Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments)

G. Executive Order 13045 (Protection of Children From Environmental Health and Safety Risks)

H. Executive Order 13211 (Actions That Significantly Affect Energy Supply, Distribution, or Use)

I. National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act of 1995

J. Executive Order 12898 (Federal Actions To Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations)

K. Congressional Review Act (CRA)

I. General Information

A. Does this action apply to me?

Entities such as industries, stormwater management districts, or publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) that discharge pollutants to waters of the United States in Maine could be indirectly affected by this rulemaking, because federal WQS promulgated by EPA are applicable to CWA regulatory programs, such as National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permitting. Citizens concerned with water quality in Maine, including members of the federally recognized Indian tribes in Maine, could also be interested in this rulemaking. Dischargers that could potentially be affected include the following:

Table 1—Dischargers Potentially Affected by This Rulemaking

Category Examples of potentially affected entities Industry Industries discharging pollutants to waters of the United States in Maine. Municipalities Publicly owned treatment works or other facilities discharging pollutants to waters of the United States in Maine. Stormwater Management Districts Entities responsible for managing stormwater runoff in the state of Maine. This table is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather provides a guide for readers regarding entities that could be indirectly affected by this action. Any parties or entities who depend upon or contribute to the quality of Maine's waters could be affected by this rule. To determine whether your facility or activities could be affected by this action, you should carefully examine this rule. If you have questions regarding the applicability of this action to a particular entity, consult Jennifer Brundage, whose contact information can be found in the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION section above.

B. How did EPA develop this final rule?

In developing this final rule, EPA carefully considered the public comments and feedback received from interested parties. EPA provided a 60-day public comment period after publishing the proposed rule in the Federal Register on April 20, 2016.[1] In addition, EPA held two virtual public hearings on June 7 and 9, 2016, to discuss the contents of the proposed rule and accept verbal public comments.

Over 100 organizations and individuals submitted comments on a range of issues. Some comments addressed issues beyond the scope of the rulemaking, and thus EPA did not consider them in finalizing this rule. In section III of this preamble, EPA discusses certain public comments so that the public is aware of the Agency's position. For a full response to these Start Printed Page 92467and all other comments, see EPA's Response to Comments (RTC) document in the official public docket.

II. Background and Summary

A. Statutory and Regulatory Background

1. Clean Water Act (CWA)

CWA section 101(a)(2) establishes as a national goal “water quality which provides for the protection and propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife, and recreation in and on the water, wherever attainable.” These are commonly referred to as the “fishable/swimmable” goals of the CWA. EPA interprets “fishable” uses to include, at a minimum, designated uses providing for the protection of aquatic communities and human health related to consumption of fish and shellfish.[2]

CWA section 303(c) (33 U.S.C. 1313(c)) directs states to adopt water quality standards (WQS) for waters under their jurisdiction subject to the CWA. CWA section 303(c)(2)(A) and EPA's implementing regulations at 40 CFR part 131 require, among other things, that a state's WQS specify appropriate designated uses of the waters, and water quality criteria to protect those uses that are based on sound scientific rationale. EPA's regulations at 40 CFR 131.11(a)(1) provide that such criteria “must be based on sound scientific rationale and must contain sufficient parameters or constituents to protect the designated use.” In addition, 40 CFR 131.10(b) provides that “[i]n designating uses of a waterbody and the appropriate criteria for those uses, the state shall take into consideration the water quality standards of downstream waters and ensure that its water quality standards provide for the attainment and maintenance of the water quality standards of downstream waters.”

States are required to review applicable WQS at least once every three years and, if appropriate, revise or adopt new standards (CWA section 303(c)(1)). Any new or revised WQS must be submitted to EPA for review, to determine whether it meets the CWA's requirements, and for approval or disapproval (CWA section 303(c)(2)(A) and (c)(3)). If EPA disapproves a state's new or revised WQS, the CWA provides the state ninety days to adopt a revised WQS that meets CWA requirements, and if it fails to do so, EPA shall promptly propose and then within ninety days promulgate such standard unless EPA approves a state replacement WQS first (CWA section 303(c)(3) and (c)(4)(A)). If the state adopts and EPA approves a state replacement WQS after EPA promulgates a standard, EPA then withdraws its promulgation. CWA section 303(c)(4)(B) authorizes the Administrator to determine, even in the absence of a state submission, that a new or revised standard is necessary to meet CWA requirements. Upon making such a determination, EPA shall promptly propose, and then within ninety days promulgate, any such new or revised standard unless prior to such promulgation, the state has adopted a revised or new WQS that EPA approves as being in accordance with the CWA.

Under CWA section 304(a), EPA periodically publishes water quality criteria recommendations for states to consider when adopting water quality criteria for particular pollutants to protect the CWA section 101(a)(2) goal uses. For example, in 2015, EPA updated its CWA section 304(a) recommended criteria for human health for 94 pollutants (the 2015 criteria update).[3] Where EPA has published recommended criteria, states should adopt water quality criteria based on EPA's CWA section 304(a) criteria, section 304(a) criteria modified to reflect site-specific conditions, or other scientifically defensible methods (40 CFR 131.11(b)(1)). CWA section 303(c)(2)(B) requires states to adopt numeric criteria for all toxic pollutants listed pursuant to CWA section 307(a)(1) for which EPA has published CWA section 304(a) criteria, as necessary to support the states' designated uses.

2. Maine Indian Settlement Acts

There are four federally recognized Indian tribes in Maine represented by five governing bodies. The Penobscot Nation and the Passamaquoddy Tribe have reservations and trust land holdings in central and coastal Maine. The Passamaquoddy Tribe has two governing bodies, one on the Pleasant Point Reservation and another on the Indian Township Reservation. The Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians and the Aroostook Band of Micmacs have trust lands farther north in the state. To simplify the discussion, EPA will refer to the Penobscot Nation and the Passamaquoddy Tribe together as the “Southern Tribes” and the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians and Aroostook Band of Micmacs as the “Northern Tribes.” EPA acknowledges that these are collective appellations the tribes themselves have not adopted, and the Agency uses them solely to simplify this discussion.

In 1980, Congress passed the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA) that resolved litigation in which the Southern Tribes asserted land claims to a large portion of the state of Maine. Public Law 96-420, 94 Stat. 1785. MICSA ratified a state statute passed in 1979, the Maine Implementing Act (MIA, 30 M.R.S. 6201, et seq.), which was designed to embody the agreement reached between the state and the Southern Tribes. In 1981, MIA was amended to include provisions for land to be taken into trust for the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, as provided for in MICSA. Public Law 96-420, 94 Stat. 1785 section 5(d)(1); 30 M.R.S. 6205-A. Since it is Congress that has plenary authority as to federally recognized Indian tribes, MIA's provisions concerning jurisdiction and the status of the tribes are effective as a result of, and consistent with, the Congressional ratification in MICSA.

In 1989, the Maine legislature passed the Micmac Settlement Act (MSA) to embody an agreement as to the status of the Aroostook Band of Micmacs. 30 M.R.S. 7201, et seq. In 1991, Congress passed the Aroostook Band of Micmacs Settlement Act (ABMSA), which ratified the MSA. Act of Nov. 26, 1991, Public Law 102-171, 105 Stat. 1143. One principal purpose of both statutes was to give the Micmacs the same settlement that had been provided to the Maliseets in MICSA. See ABMSA 2(a)(4) and (5). In 2007, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit confirmed that the Micmacs and Maliseets are subject to the same jurisdictional provisions in MICSA. Aroostook Band of Micmacs v. Ryan, 484 F.3d 41 (1st Cir. 2007). Where appropriate, this preamble discussion will refer to the combination of MICSA, MIA, ABMSA, and MSA as the “Indian settlement acts” or “settlement acts.”

3. EPA's Disapprovals of Portions of Maine's Water Quality Standards

On February 2, March 16, and June 5, 2015, EPA disapproved a number of Maine's new and revised WQS. These decision letters are available in the docket for this rulemaking. They were prompted by an ongoing lawsuit Start Printed Page 92468initiated by Maine against EPA.[4] As discussed in the preamble to the proposed rule (see 81 FR 23239, 23241-23242), some of the disapprovals applied only to waters in Indian lands in Maine, while others applied to waters throughout the state or to waters in the state outside of Indian lands.[5] EPA concluded that the disapproved WQS did not adequately protect designated uses related to the protection of human health and/or aquatic life.[6] EPA requested the state to revise its WQS to address the issues identified in the disapprovals. The statutory 90-day timeframe provided to the state to revise its WQS has passed with respect to all of the disapproved WQS. EPA is required by the CWA to promptly propose and then, within 90 days of proposal, to promulgate federal standards unless, in the meantime, the state adopts and EPA approves state replacement WQS that address EPA's disapproval. The state has not adopted WQS revisions to address the disapprovals. Having published the proposed rule on April 20, 2016, EPA is today finalizing the rule. With the exception of minor revisions to several human health criteria as noted in section II.B.1.a and two small changes discussed in section II.B.2, EPA's final rule is identical to the proposed rule.

4. Scope of Action

a. Scope of Promulgation Related to Disapprovals

To address the disapprovals discussed in section II.A.3, EPA is promulgating human health criteria (HHC) for toxic pollutants and six other WQS that apply only to waters in Indian lands; two WQS for all waters in Maine including waters in Indian lands; and one WQS for waters in Maine outside of Indian lands. For the purpose of this rulemaking, “waters in Indian lands” are those waters in the tribes' reservations and trust lands as provided for in the settlement acts.

b. Scope of Promulgation Related to the Administrator's Determination

On April 20, 2016, EPA made a CWA section 303(c)(4)(B) determination that, for any waters in Maine where there is a sustenance fishing designated use and Maine's existing HHC are in effect, new or revised HHC for the protection of human health in Maine are necessary to meet the requirements of the CWA. EPA proposed (see 81 FR 23239, 23242-23243), and is now finalizing, HHC for toxic pollutants, in accordance with the CWA section 303(c)(4)(B) determination, for the following waters: (1) Waters in Indian lands in the event that a court determines that EPA's disapprovals of HHC for such waters were unauthorized and that Maine's existing HHC are in effect; [7] and (2) waters where there is a sustenance fishing designated use outside of waters in Indian lands.[8]

5. Applicability of Water Quality Standards

These water quality standards apply to the categories of waters for CWA purposes, as described in II.B below. Although EPA is finalizing WQS to address the standards that it disapproved or for which it has made a determination, Maine continues to have the option to adopt and submit to EPA new or revised WQS that remedy the issues identified in the disapprovals and determination, consistent with CWA section 303(c) and EPA's implementing regulations at 40 CFR part 131.

Some commenters urged EPA to finalize its rule without any further delay. Conversely, the state noted that EPA should give it additional time to adopt and submit its own WQS to address EPA's disapprovals. EPA acknowledges the perspectives of all of these commenters. EPA agrees that there is a compelling need to finalize the WQS, particularly in waters in Indian lands in Maine. For many pollutants, there are no criteria in effect for CWA purposes in waters in Indian lands, including most human health criteria, and it is important to remedy this gap in protection without further delay where possible. Further, the tribes have repeatedly expressed their desire for, and the importance of, their right to a sustenance fishing way of life, reserved for them under the settlement acts, to be protected. EPA, as a federal government agency, is taking action to protect that right, consistent with the settlement acts and CWA, as described further below.

EPA also agrees that the CWA is intended to protect the Nation's waters through a system of cooperative federalism, with states having the primary responsibility of establishing protective WQS for waters under their jurisdiction. However, Maine is challenging EPA's disapproval of the Start Printed Page 92469HHC for waters in Indian lands in federal court, and it commented adversely on EPA's proposed HHC, pH, bacteria, and tidal temperature criteria for waters in Indian lands. Consequently, EPA has no assurance that Maine will develop WQS that EPA can approve as scientifically defensible and protective of Maine's designated uses.

Having considered these comments, EPA, in keeping with its statutory obligation to promulgate WQS within 90 days after proposing them and the need for these WQS to meet the requirements of the CWA, is finalizing the WQS.

In the April 20, 2016, Federal Register notice, EPA proposed that if Maine adopted and submitted WQS that meet CWA requirements after EPA finalized its proposed rule, they would become effective for CWA purposes upon EPA approval and EPA's corresponding promulgated WQS would no longer apply. No commenters supported this proposal. Two commenters objected to it, and one asked that EPA specify that WQS adopted by the state would have to be at least as stringent as the federally proposed WQS for EPA to approve and make the state WQS effective for CWA purposes.

Upon consideration of comments received on its proposed rule, EPA decided not to finalize the above proposed approach. Consistent with 40 CFR 131.21(c), EPA's federally promulgated WQS are and will be applicable for purposes of the CWA until EPA withdraws those federally promulgated WQS. EPA would undertake a rulemaking to withdraw the federal WQS if and when Maine adopts and EPA approves corresponding WQS that meet the requirements of section 303(c) of the CWA and EPA's implementing regulations at 40 CFR part 131.

B. Description of Final Rule

1. Final WQS for Waters in Indian Lands in Maine and for Waters outside of Indian Lands in Maine Where the Sustenance Fishing Designated Use Established by 30 M.R.S. 6207(4) and (9) Applies

a. Human Health Criteria for Toxic Pollutants

After consideration of all comments received on EPA's proposed rule, EPA is finalizing the proposed criteria for 96 toxic pollutants in this rule applicable to waters in Indian lands.[9] Table 2 provides the criteria for each pollutant as well as the HHC inputs used to derive each one. These criteria also apply to any waters that are covered by the determination referenced in section II.A.4.

Start Printed Page 92470Start Printed Page 92472Table 2—Final HHC and Key Parameters Used in Their Derivation

Chemical name CAS No. Cancer slope factor, CSF (per mg/kg·d) Relative source contribution RSC (-) Reference dose, RfD (mg/kg·d) Bioaccumu- lation factor for trophic level 2 (L/kg tissue) Bioaccumu- lation factor for trophic level 3 (L/kg tissue) Bioaccumu- lation factor for trophic level 4 (L/kg tissue) Bioconcen- tration factor (L/kg tissue) e Water & organisms (µg/L) Organisms only (µg/L) 1 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane 79-34-5 0.2 5.7 7.4 8.4 0.09 0.2 2 1,1,2-Trichloroethane 79-00-5 0.057 6.0 7.8 8.9 0.31 0.66 3 1,1-Dichloroethylene 75-35-4 0.20 0.05 2.0 2.4 2.6 300 1000 4 1,2,4,5-Tetrachlorobenzene 95-94-3 0.20 0.0003 17,000 2,900 1,500 0.002 0.002 5 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene 120-82-1 0.029 2,800 1,500 430 0.0056 0.0056 6 1,2-Dichlorobenzene 95-50-1 0.20 0.3 52 71 82 200 300 7 1,2-Dichloropropane 78-87-5 0.036 2.9 3.5 3.9 2.3 8 1,2-Diphenylhydrazine 122-66-7 0.8 18 24 27 0.01 0.02 9 1,2-Trans-Dichloroethylene 156-60-5 0.20 0.02 3.3 4.2 4.7 90 300 10 1,3-Dichlorobenzene 541-73-1 0.20 0.002 31 120 190 1 1 11 1,3-Dichloropropene 542-75-6 0.122 2.3 2.7 3.0 0.21 0.87 12 1,4-Dichlorobenzene 106-46-7 0.20 0.07 28 66 84 70 13 2,4,5-Trichlorophenol 95-95-4 0.20 0.1 100 140 160 40 40 14 2,4,6-Trichlorophenol 88-06-2 0.011 94 130 150 0.20 0.21 15 2,4-Dichlorophenol 120-83-2 0.20 0.003 31 42 48 4 4 16 2,4-Dimethylphenol 105-67-9 0.20 0.02 4.8 6.2 7.0 80 200 17 2,4-Dinitrophenol 51-28-5 0.20 0.002 a 4.4 a 4.4 a 4.4 9 30 18 2,4-Dinitrotoluene 121-14-2 0.667 2.8 3.5 3.9 0.036 0.13 19 2-Chloronaphthalene 91-58-7 0.80 0.08 150 210 240 90 90 20 2-Chlorophenol 95-57-8 0.20 0.005 3.8 4.8 5.4 20 60 21 2-Methyl-4,6-Dinitrophenol 534-52-1 0.20 0.0003 6.8 8.9 10 1 2 22 3,3′-Dichlorobenzidine 91-94-1 0.45 44 60 69 0.0096 0.011 23 4,4′-DDD 72-54-8 0.24 33,000 140,000 240,000 9.3E-06 9.3E-06 24 4,4′-DDE 72-55-9 0.167 270,000 1,100,000 3,100,000 1.3E-06 1.3E-06 25 4,4'-DDT 50-29-3 0.34 35,000 240,000 1,100,000 2.2E-06 2.2E-06 26 Acenaphthene 83-32-9 0.20 0.06 a 510 a 510 a 510 6 7 27 Acrolein 107-02-8 0.20 0.0005 1.0 1.0 1.0 3 28 Aldrin 309-00-2 17 18,000 310,000 650,000 5.8E-08 5.8E-08 29 alpha-BHC 319-84-6 6.3 1,700 1,400 1,500 2.9E-05 2.9E-05 30 alpha-Endosulfan 959-98-8 0.20 0.006 130 180 200 2 2 31 Anthracene 120-12-7 0.20 0.3 a 610 a 610 a 610 30 30 32 Antimony 7440-36-0 0.40 0.0004 1 5 40 33 Benzene 71-43-2 b 0.055 3.6 4.5 5.0 0.40 1.2 34 Benzo (a) Anthracene 56-55-3 0.73 a 3,900 a 3,900 a 3,900 9.8E-05 9.8E-05 35 Benzo (a) Pyrene 50-32-8 7.3 a 3,900 a 3,900 a 3,900 9.8E-06 9.8E-06 36 Benzo (b) Fluoranthene 205-99-2 0.73 a 3,900 a 3,900 a 3,900 9.8E-05 9.8E-05 37 Benzo (k) Fluoranthene 207-08-9 0.073 a 3,900 a 3,900 a 3,900 0.00098 0.00098 38 beta-BHC 319-85-7 1.8 110 160 180 0.0010 0.0011 39 beta-Endosulfan 33213-65-9 0.20 0.006 80 110 130 3 3 40 Bis(2-Chloro-1-Methylethyl) Ether 108-60-1 0.20 0.04 6.7 8.8 10 100 300 41 Bis(2-Chloroethyl) Ether 111-44-4 1.1 1.4 1.6 1.7 0.026 0.16 42 Bis(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate 117-81-7 0.014 a 710 a 710 a 710 0.028 0.028 43 Bromoform 75-25-2 0.0045 5.8 7.5 8.5 4.0 8.7 44 Butylbenzyl Phthalate 85-68-7 0.0019 a 19,000 a 19,000 a 19,000 0.0077 0.0077 45 Carbon Tetrachloride 56-23-5 0.07 9.3 12 14 0.2 0.3 46 Chlordane 57-74-9 0.35 5,300 44,000 60,000 2.4E-05 2.4E-05 47 Chlorobenzene 108-90-7 0.20 0.02 14 19 22 40 60 48 Chlorodibromomethane 124-48-1 0.040 3.7 4.8 5.3 1.5 49 Chrysene 218-01-9 0.0073 a 3,900 a 3,900 a 3,900 0.0098 50 Cyanide 57-12-5 0.20 0.0006 1 4 30 51 Dibenzo (a,h) Anthracene 53-70-3 7.3 a 3,900 a 3,900 a 3,900 9.8E-06 9.8E-06 52 Dichlorobromomethane 75-27-4 0.034 3.4 4.3 4.8 2.0 53 Dieldrin 60-57-1 16 14,000 210,000 410,000 9.3E-08 9.3E-08 54 Diethyl Phthalate 84-66-2 0.20 0.8 a 920 a 920 a 920 50 50 55 Dimethyl Phthalate 131-11-3 0.20 10 a 4,000 a 4,000 a 4,000 100 100 56 Di-n-Butyl Phthalate 84-74-2 0.20 0.1 a 2,900 a 2,900 a 2,900 2 2 57 Dinitrophenols 25550-58-7 0.20 0.002 1.51 10 70 58 Endosulfan Sulfate 1031-07-8 0.20 0.006 88 120 140 3 3 59 Endrin 72-20-8 0.80 0.0003 4,600 36,000 46,000 0.002 0.002 Start Printed Page 92471 60 Endrin Aldehyde 7421-93-4 0.80 0.0003 440 920 850 0.09 0.09 61 Ethylbenzene 100-41-4 0.20 0.022 100 140 160 8.9 9.5 62 Fluoranthene 206-44-0 0.20 0.04 a 1,500 a 1,500 a 1,500 1 1 63 Fluorene 86-73-7 0.20 0.04 230 450 710 5 5 64 gamma-BHC (Lindane) 58-89-9 0.50 0.0047 1,200 2,400 2,500 0.33 65 Heptachlor 76-44-8 4.1 12,000 180,000 330,000 4.4E-07 4.4E-07 66 Heptachlor Epoxide 1024-57-3 5.5 4,000 28,000 35,000 2.4E-06 2.4E-06 67 Hexachlorobenzene 118-74-1 1.02 18,000 46,000 90,000 5.9E-06 5.9E-06 68 Hexachlorobutadiene 87-68-3 0.04 23,000 2,800 1,100 0.0007 0.0007 69 Hexachlorocyclohexane-Technical 608-73-1 1.8 160 220 250 0.00073 0.00076 70 Hexachlorocyclopentadiene 77-47-4 0.20 0.006 620 1,500 1,300 0.3 0.3 71 Hexachloroethane 67-72-1 0.04 1,200 280 600 0.01 0.01 72 Indeno (1,2,3-cd) Pyrene 193-39-5 0.73 a 3,900 a 3,900 a 3,900 9.8E-05 9.8E-05 73 Isophorone 78-59-1 0.00095 1.9 2.2 2.4 28 140 74 Methoxychlor 72-43-5 0.80 2E-05 1,400 4,800 4,400 0.001 75 Methylene Chloride 75-09-2 0.002 1.4 1.5 1.6 90 76 Methylmercury 22967-92-6 2.70E-05 0.0001 c 0.02 (mg/kg) 77 Nickel 7440-02-0 0.20 0.02 47 20 20 78 Nitrobenzene 98-95-3 0.20 0.002 2.3 2.8 3.1 10 40 79 Nitrosamines 43.46 0.20 0.00075 0.032 80 N-Nitrosodibutylamine 924-16-3 5.43 3.38 0.00438 0.0152 81 N-Nitrosodiethylamine 55-18-5 43.46 0.20 0.00075 0.032 82 N-Nitrosodimethylamine 62-75-9 51 0.026 0.00065 0.21 83 N-Nitrosodi-n-propylamine 621-64-7 7.0 1.13 0.0042 0.035 84 N-Nitrosodiphenylamine 86-30-6 0.0049 136 0.40 0.42 85 N-Nitrosopyrrolidine 930-55-2 2.13 0.055 2.4 86 Pentachlorobenzene 608-93-5 0.20 0.0008 3,500 4,500 10,000 0.008 0.008 87 Pentachlorophenol 87-86-5 0.4 44 290 520 0.003 0.003 88 Phenol 108-95-2 0.20 0.6 1.5 1.7 1.9 3,000 20,000 89 Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) 1336-36-3 2 31,200 d 4E-06 d 4E-06 90 Pyrene 129-00-0 0.20 0.03 a 860 a 860 a 860 2 2 91 Selenium 7782-49-2 0.20 0.005 4.8 20 60 92 Toluene 108-88-3 0.20 0.0097 11 15 17 24 39 93 Toxaphene 8001-35-2 1.1 1,700 6,600 6,300 5.3E-05 5.3E-05 94 Trichloroethylene 79-01-6 0.05 8.7 12 13 0.3 0.5 95 Vinyl Chloride 75-01-4 1.5 1.4 1.6 1.7 0.019 0.12 96 Zinc 7440-66-6 0.20 0.3 47 300 400 a This bioaccumulation factor was estimated from laboratory-measured bioconcentration factors; EPA multiplied this bioaccumulation factor by the overall fish consumption rate of 286 g/day to calculate the human health criteria. b EPA's CWA section 304(a) HHC for benzene use a CSF range of 0.015 to 0.055 per mg/kg-day. EPA used the higher end of the CSF range (0.055 per mg/kg-day) to derive the final benzene criteria. c This criterion is expressed as the fish tissue concentration of methylmercury (mg methylmercury/kg fish) and applies equally to fresh and marine waters. See Water Quality Criterion for the Protection of Human Health: Methylmercury (EPA-823-R-01-001, January 3, 2001) for how this value is calculated using the criterion equation in EPA's 2000 Methodology rearranged to solve for a protective concentration in fish tissue rather than in water. d This criterion applies to total PCBs (i.e., the sum of all congener or isomer or homolog or Aroclor analyses). e EPA multiplied this bioconcentration factor by the overall fish consumption rate of 286 g/day to calculate the human health criteria. i. Sustenance Fishing Designated Use and Tribal Target Population

In its February 2015 decision, EPA concluded that MICSA granted the state authority to set WQS in waters in Indian lands. EPA also concluded that in assessing whether the state's WQS were approvable for waters in Indian lands, EPA must effectuate the CWA requirement that WQS must protect applicable designated uses and be based on sound science in consideration of the fundamental purpose for which land was set aside for the tribes under the Indian settlement acts in Maine. EPA found that those settlement acts provide for land to be set aside as a permanent land base for the Indian tribes in Maine, in order for the tribes to be able to continue their unique cultural practices, including the ability to exercise sustenance fishing practices. Accordingly, EPA interpreted the state's “fishing” designated use, as applied to waters in Indian lands, to mean “sustenance fishing” and approved it as such. EPA also approved a specific sustenance fishing right reserved in MIA sections 6207(4) and (9) as a designated use for all inland waters of the Southern Tribes' reservations. Against this backdrop, EPA approved or disapproved all of Maine's HHC for toxic pollutants as applied to waters in Indian lands after evaluating whether they satisfied CWA requirements.

EPA determined that the tribal populations must be treated as the general target population in waters in Indian lands. EPA disapproved many of Maine's HHC for toxic pollutants based on EPA's conclusion that they do not adequately protect the health of tribal sustenance fishers in waters in Indian lands. EPA concluded that the disapproved HHC did not support the designated use of sustenance fishing in such waters because they were not based on the higher, unsuppressed fish consumption rates that reflect the tribes' sustenance fishing practices. Accordingly, EPA proposed, and is now finalizing, HHC that EPA has determined will protect the sustenance fishing designated use, based on sound science and consistent with the CWA and EPA regulations and policy.

ii. General Recommended Approach for Deriving HHC

HHC for toxic pollutants are designed to minimize the risk of adverse cancer and non-cancer effects occurring from lifetime exposure to pollutants through the ingestion of drinking water and consumption of fish/shellfish obtained from inland and nearshore waters. EPA's practice is to establish CWA section 304(a) HHC for the combined activities of drinking water and consuming fish/shellfish obtained from inland and nearshore waters, and separate CWA section 304(a) HHC for consuming only fish/shellfish originating from inland and nearshore waters. The latter criteria apply in cases where the designated uses of a waterbody include supporting fish/shellfish for human consumption but not drinking water supply sources (e.g., in non-potable estuarine waters).

The criteria are based on two types of biological endpoints: (1) Carcinogenicity and (2) systemic toxicity (i.e., all adverse effects other than cancer). EPA takes an integrated approach and considers both cancer and non-cancer effects when deriving HHC. Where sufficient data are available, EPA derives criteria using both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic toxicity endpoints and recommends the lower value. HHC for carcinogenic effects are typically calculated using the following input parameters: Cancer slope factor, excess lifetime cancer risk level, body weight, drinking water intake rate, fish consumption rate(s), and bioaccumulation factor(s). HHC for noncarcinogenic and nonlinear carcinogenic effects are typically calculated using reference dose, relative source contribution (RSC), body weight, drinking water intake rate, fish consumption rate(s) and bioaccumulation factor(s). EPA selects a mixture of high-end and central (mean) tendency inputs to the equation in order to derive recommended criteria that “afford an overall level of protection targeted at the high end of the general population (i.e., the target population or the criteria-basis population).” [10]

EPA received comments supporting and opposing specific input parameters EPA used to derive the proposed HHC. The specific input parameters used are explained in the following paragraphs.

iii. Maine-Specific HHC Inputs

I. Cancer Risk Level. As set forth in EPA's 2000 Methodology for Deriving Ambient Water Quality Criteria for the Protection of Human Health (the “2000 Methodology”), EPA calculates its CWA section 304(a) HHC at concentrations corresponding to a 10−[6] cancer risk level (CRL), meaning that if exposure were to occur as set forth in the CWA section 304(a) methodology at the prescribed concentration over the course of one's lifetime, then the risk of developing cancer from the exposure as described would be a one in a million increment above the background risk of developing cancer from all other exposures.[11]

In this rule, EPA derived the final HHC for carcinogens using a 10−[6] CRL, consistent with EPA's 2000 Methodology and with Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) Rule Chapter 584, which specifies that water quality criteria for carcinogens must be based on a 10−[6] CRL, and which EPA approved for waters in Indian lands on February 2, 2015.[12] The HHC provide the tribes engaged in sustenance fishing in waters in Indian lands in Maine with an equivalent level of cancer risk protection (i.e., 10−6) as is afforded to the general population in Maine outside of waters in Indian lands.

EPA received comments in favor of using the proposed 10−6 CRL level as well as recommendations for higher and lower CRLs. Responses to those comments are summarized in section III.D.5.

II. Cancer Slope Factor and Reference Dose. For noncarcinogenic toxicological effects, EPA uses a chronic-duration oral reference dose (RfD) to derive HHC. An RfD is an estimate (with uncertainty spanning perhaps an order of magnitude) of a daily oral exposure of an individual to a substance that is likely to be without an appreciable risk of deleterious effects during a lifetime. For carcinogenic toxicological effects, EPA uses an oral cancer slope factor (CSF) to derive HHC. The oral CSF is an upper bound, approximating a 95% confidence limit, on the increased cancer risk from a lifetime oral exposure to a stressor.

EPA did not receive any comments on the pollutant-specific RfDs or CSFs used in the derivation of the proposed criteria, which were based on EPA's National Recommended Water Quality Criteria.[13] EPA has used the same values to derive the final HHC.

III. Body Weight. The final HHC were calculated using the proposed body weight of 80 kilograms (kg), consistent with the default body weight used in EPA's most recent National Start Printed Page 92473Recommended Water Quality Criteria.[14] This body weight is the average weight of a U.S. adult age 21 and older, based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (“NHANES”) data from 1999 to 2006.[15] EPA received one comment regarding body weight, which requested that EPA use a body weight of 70 kg. However, the commenter did not present a sound scientific rationale to support the use of a different body weight. See Topic 6 of the RTC document for a more detailed response.

IV. Drinking water intake. The final HHC were calculated using the proposed drinking water intake rate of 2.4 liters per day (L/day), consistent with the default drinking water intake rate used in EPA's most recent National Recommended Water Quality Criteria.[16] This rate represents the per capita estimate of combined direct and indirect community water ingestion at the 90th percentile for adults ages 21 and older.[17] EPA did not receive any comments regarding the proposed drinking water intake rate.

V. Bioaccumulation Factors (BAFs) and Bioconcentration Factors (BCFs). The final HHC were calculated using the proposed pollutant-specific BAFs or BCFs, consistent with the factors used in EPA's most recent National Recommended Water Quality Criteria.[18] These factors are used to relate aqueous pollutant concentrations to predicted pollutant concentrations in the edible portions of ingested species. EPA did not receive any comments regarding specific proposed BAFs or BCFs.

VI. Fish Consumption Rate (FCR). In finalizing the HHC, EPA used the proposed FCR of 286 g/day to represent present day sustenance level fish consumption for waters in Indian lands. This FCR supports the designated use of sustenance fishing. EPA selected this consumption rate based on information contained in an historical/anthropological study, entitled the Wabanaki Cultural Lifeways Exposure Scenario [19] (“Wabanaki Study”), which was completed in 2009. EPA also consulted with the tribes in Maine about the Wabanaki Study and their sustenance fishing uses of the waters in Indian lands. There has been no contemporary local survey of current fish consumption that documents fish consumption rates for sustenance fishing in the waters in Indian lands in Maine. In the absence of such information, EPA concluded that the Wabanaki Study contains the best currently available estimate for contemporary tribal sustenance level fish consumption for waters where the sustenance fishing designated use applies.

EPA received many comments that agreed and some that disagreed with EPA's selection of the proposed FCR of 286 g/day. Responses to those comments can be found in section III.D of this preamble and, in further detail, in Topic 3 of the RTC document.

VII. Relative Source Contribution (RSC). For pollutants that exhibit a threshold of exposure before deleterious effects occur, as is the case for noncarcinogens and nonlinear carcinogens, EPA applied a RSC to account for other potential human exposures to the pollutant.[20] Other sources of exposure might include, but are not limited to, exposure to a particular pollutant from non-fish food consumption (e.g., consumption of fruits, vegetables, grains, meats, or poultry), dermal exposure, and inhalation exposure. For substances for which the toxicity endpoint is carcinogenicity based on a linear low-dose extrapolation, only the exposures from drinking water and fish ingestion are reflected in HHC; no other potential sources of exposure to pollutants or other potential exposure pathways have been considered in developing HHC.[21] In these situations, HHC are derived with respect to the incremental lifetime cancer risk posed by the presence of a substance in water, rather than an individual's total risk from all sources of exposure.

As in the proposed HHC, for the pollutants included in EPA's 2015 criteria update, EPA used the same RSCs in the final HHC as were used in the criteria update. Also as in the proposed HHC, for pollutants where EPA did not update the section 304(a) HHC in 2015, EPA used a default RSC of 0.20 to derive the final HHC except for antimony, for which EPA used an RSC of 0.40 consistent with the RSC value used the last time the Agency updated this criterion. EPA did not receive any comments on specific RSCs used in the derivation of the proposed criteria.

2. Final WQS for Waters in Indian Lands in Maine

a. Bacteria Criteria

i. Recreational Bacteria Criteria

EPA is finalizing the proposed year-round recreational bacteria criteria for Class AA, A, B, C, GPA, SA, SB and SC waters in Indian lands. The magnitude criteria are expressed in terms of Escherichia coli colony forming units per 100 milliliters (cfu/100 ml) for fresh waters and Enterococcus spp. colony forming units per 100 milliliters (cfu/100 ml) for marine waters and are based on EPA's 2012 Recreational Water Quality Criteria (RWQC) recommendations.[22]

Several comments supported EPA's proposed rule and the year round applicability of the criteria. Maine DEP objected to EPA's inclusion of wildlife sources in the scope of the bacteria criteria and requested that the criteria not be applicable from October 1-May 14, similar to Maine's disapproved criteria. For the reasons discussed in section III.E.2., EPA has determined that, based on best available information, it is necessary to include wildlife sources in the scope of the criteria, and to apply the criteria year round, in order to protect human health and the designated use of recreation in and on the water.

ii. Shellfishing Bacteria Criteria

EPA's final bacteria rule for Class SA shellfish harvesting areas for waters in Start Printed Page 92474Indian lands differs slightly from the proposed numeric total coliform bacteria criteria, as a result of comments from the state. Maine DEP requested EPA to express the criteria in terms of fecal coliform bacteria rather than total coliform bacteria, noting that the National Shellfish Sanitation Program (NSSP) allows the use of either indicator, that Maine DEP sets permit limits on fecal coliform bacteria rather than total coliform, and that Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR) uses fecal coliform bacteria as its indicator parameter when making shellfish area opening/closure decisions. Maine DMR requested EPA not to specify a specific numeric standard but rather to promulgate the same narrative criterion that applies to Class SB and SC waters. For those classes of waters, Maine's WQS provide that instream bacteria levels may not exceed the criteria recommended under the NSSP.

The NSSP is the federal/state cooperative program recognized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference (ISSC) for the sanitary control of shellfish produced and sold for human consumption.

EPA agrees that the NSSP allows for the use of either fecal coliform bacteria or total coliform bacteria as the indicator organism to protect shellfish harvesting. The current NSSP recommendations [23] for those organisms are consistent with EPA's national recommended water quality criteria.[24] The NSSP recommendations for fecal coliform standards and sampling protocols are set forth in Section II. Model Ordinance Chapter IV. Growing Areas .02 Microbial Standards (pages 51-54). The NSSP recommendations for total coliform standards and sampling protocols are set forth in Section IV, Guidance Documents Chapter II. Growing Areas .01 Total Coliform Standards (pages 216-219). Both sets of recommendations apply to various types of shellfish growing areas including remote status, areas affected by point source pollution, and areas affected by nonpoint source pollution.

In light of the state's concerns and suggestions, EPA's final rule contains a narrative criterion similar to Maine's approved criterion for Class SB and SC waters. The final rule provides “The numbers of total coliform bacteria or other specified indicator organisms in samples representative of the waters in shellfish harvesting areas may not exceed the criteria recommended under the National Shellfish Sanitation Program, United States Food and Drug Administration as set forth in the Guide for the Control of Molluscan Shellfish, 2015 Revision.” EPA has added a specific reference to the date of the NSSP recommendations because there are legal constraints on incorporating future recommendations by reference. The NSSP 2015 recommendations are available online at: http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/FederalStateFoodPrograms/ucm2006754.htm. The recommendations are also included in the docket for this rulemaking, which is available both online at regulations.gov and in person at the EPA Docket Center Reading Room, William Jefferson Clinton West Building, Room 3334, 1301 Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20004, and (202) 566-1744. Finally, the 2015 NSSP recommendations are obtainable from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Shellfish and Aquaculture Policy Branch, 5100 Paint Branch Parkway (HFS-325), College Park, MD 20740.

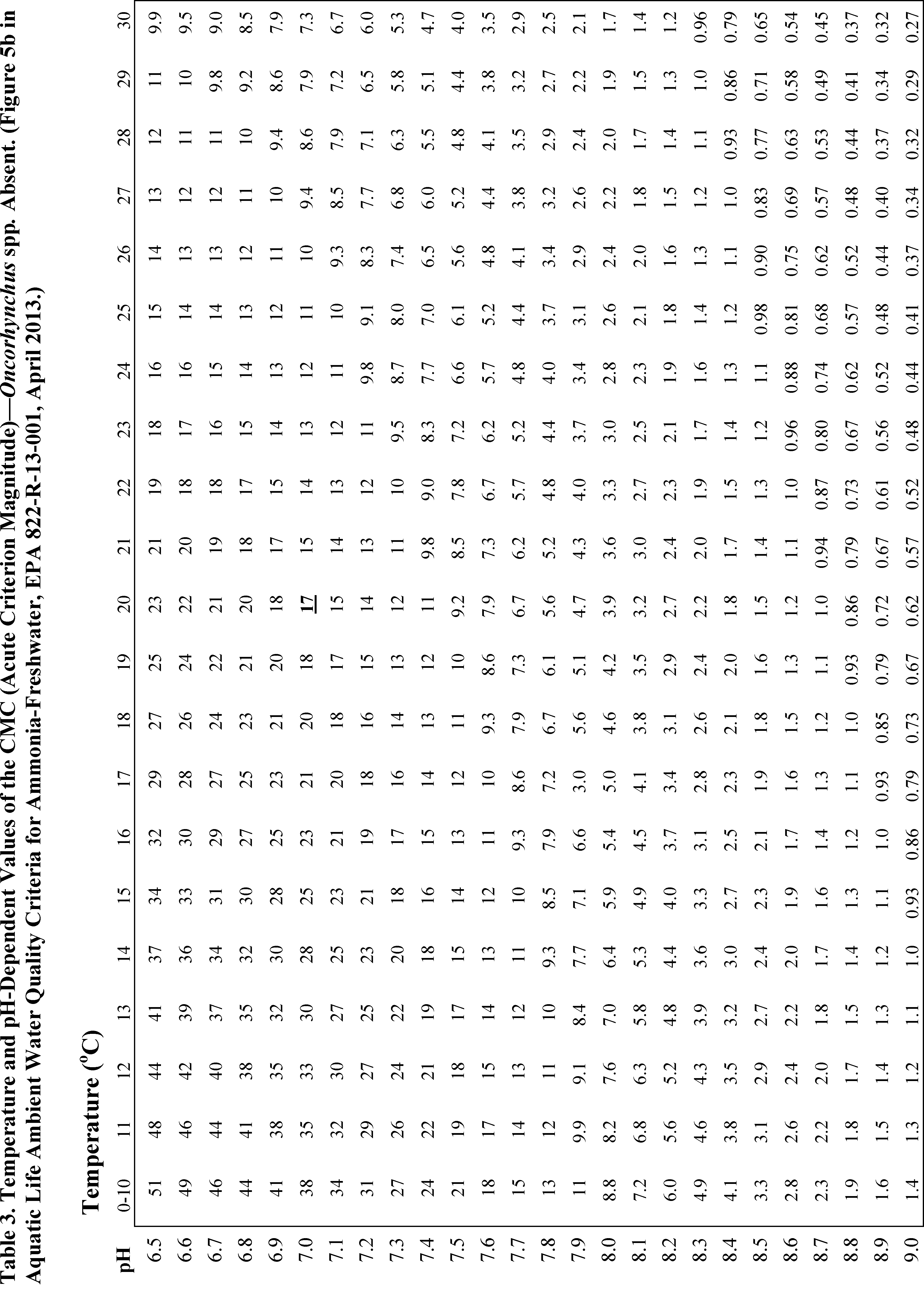

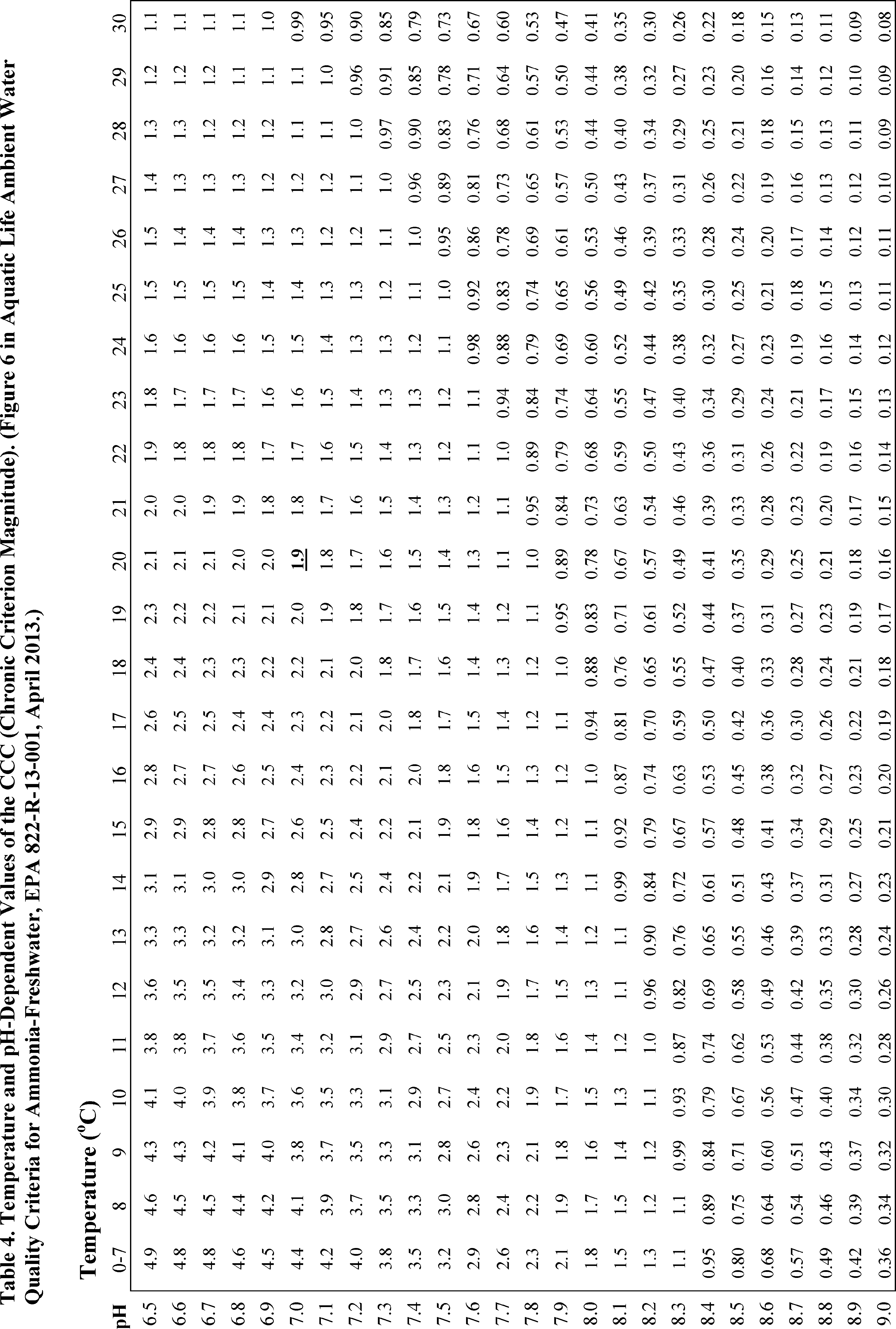

b. Ammonia Criteria for Fresh Waters

EPA is finalizing the proposed ammonia criteria for fresh waters in Indian lands to protect aquatic life. The criteria are based on EPA's 2013 updated CWA section 304(a) recommended ammonia criteria.[25] They are expressed as functions of temperature and pH, so the applicable criteria vary by waterbody, depending on the temperature and pH of those waters. EPA received several comments in support of the proposed ammonia criteria, and received no comments requesting changes.

c. pH Criterion for Fresh Waters

EPA is finalizing the proposed pH criterion of 6.5 to 8.5 to protect aquatic life in fresh waters in Indian lands. The criterion is based on EPA's 1986 national recommended criterion.[26] EPA received comments from the state and one industry, both requesting that Maine's pH criterion of 6.0-8.5 be retained. However, EPA does not agree that 6.0 adequately protects aquatic life and notes in particular that pH values of 6.0 and lower have been shown to be detrimental to sensitive aquatic life, such as developing Atlantic salmon eggs and smolts.[27 28 29] See Topic 11 of the RTC document for more detailed responses to comments.

d. Temperature Criteria for Tidal Waters

EPA is finalizing the proposed temperature criteria for tidal waters in Indian lands. The criteria will assure protection of the indigenous marine community characteristic of the intertidal zone at Pleasant Point in Passamaquoddy Bay, and are consistent with EPA's CWA section 304(a) recommended criteria for tidal waters.[30] They include a maximum summer weekly average temperature and a maximum weekly average temperature rise over reference site baseline conditions.

Maine DEP commented with concerns about the difficulty of finding reference sites to determine baseline temperatures and a question about whether there should be a baseline established for each season. EPA is confident that reference sites will not be difficult to identify, and there is no need to establish separate baselines outside the defined summer season. See Topic 12 of the RTC document for a more detailed response.

e. Natural Conditions Provisions

EPA is finalizing the proposed rule for waters in Indian lands that stated that Maine's natural conditions provisions in 38 M.R.S. 420(2.A) and 464(4.C) do not apply to water quality criteria intended to protect public health. EPA received several comments in support of the proposed rule, and received no comments requesting changes.

f. Mixing Zone Policy

EPA is finalizing the proposed mixing zone policy for waters in Indian lands with one small change to the Start Printed Page 92475prohibition of mixing zones for bioaccumulative pollutants. Specifically, in order to avoid confusion over what is meant by “bioaccumulative pollutants” for the purpose of this rule, EPA has added a parenthetical definition which specifies that bioaccumulative pollutants are those “chemicals for which the bioconcentration factors (BCF) or bioaccumulation factors (BAF) are greater than 1,000.” This definition is based on EPA's definition of bioaccumulation for chemical substances found at 64 FR 60194 (November 4, 1999).

EPA received several comments in support of the mixing zone policy. One of those commenters added that a total ban on mixing zones would be preferable. Two commenters asserted that EPA does not have the legal authority or the scientific basis to ban mixing zones for bioaccumulative pollutants outside the Great Lakes. EPA disagrees, for the reasons discussed in section III.E.1 of this preamble. One commenter raised comments about thermal mixing zones specific to its facility, and EPA's response to those comments are contained in the RTC document at Topic 9.

3. Final WQS for All Waters in Maine

a. Dissolved Oxygen for Class A Waters

EPA is finalizing the proposed dissolved oxygen criteria for all Class A waters in Maine. The rule provides that dissolved oxygen shall not be less than 7 ppm (7 mg/L) or 75% of saturation, whichever is higher, year-round. For the period from October 1 through May 14, in fish spawning areas, the 7-day mean dissolved oxygen concentration shall not be less than 9.5 ppm (9.5 mg/L), and the 1-day minimum dissolved oxygen concentration shall not be less than 8 ppm (8.0 mg/L). EPA received several comments in support of the proposed criteria, and received no comments requesting changes.

b. Waiver or Modification of WQS

EPA is finalizing the proposed rule stating that 38 M.R.S. 363-D, which allows waivers of state law in the event of an oil spill, does not apply to state or federal WQS applicable to waters in Maine, including designated uses, criteria to protect designated uses, and antidegradation requirements. EPA received several comments in support of the proposed rule, and received no comments requesting changes.

4. Final WQS for Waters in Maine Outside of Indian Lands

a. Phenol HHC for Consumption of Water Plus Organisms

EPA is finalizing the proposed phenol HHC for consumption of water plus organisms of 4000 μg/L, for waters in Maine outside of Indian lands. The criterion is consistent with EPA's June 2015 national criteria recommendation,[31] except that EPA used Maine's default fish consumption rate for the general population of 32.4 g/day, consistent with DEP Rule Chapter 584.[32] EPA received several comments in support of the proposed rule, and received no comments requesting changes.

III. Summary of Major Comments Received and EPA's Response

A. Overview of Comments

EPA received 104 total comments, 100 of which are unique comments. The vast majority of the comments were general statements of support for EPA's proposed rule from private citizens, including tribal members. Tribes and others provided substantive comments that also were generally supportive regarding the importance of protecting the designated use of sustenance fishing, identifying tribes as the target population, and using a 286 g/day fish consumption rate.

EPA also received comments critical of the proposal, principally from the Maine Attorney General and DEP, a single discharger and a coalition of dischargers, and two trade organizations. The focus of the remainder of this section III identifies and responds to the major adverse comments. Additionally, a comprehensive RTC document addressing all comments received is included in the docket for this rulemaking.

B. Maine Indian Settlement Acts

Before providing a more detailed discussion of the rationale relating to each element of EPA's analysis supporting this promulgation, the Agency first addresses a general complaint made by several commenters that EPA has developed a complex rationale for its disapproval of Maine's HHC and corresponding promulgation.

EPA acknowledges that there are several steps in the Agency's analysis of how Maine's WQS must protect the uses of the waters in Indian lands, including application of the Agency's expert scientific and policy judgment. The basic concepts are as follows:

- The Indian settlement acts provide for the Indian tribes to fish for their individual sustenance in waters in Indian lands and effectively establish a sustenance fishing designated use cognizable under the CWA for such waters.

- The CWA and EPA's regulations mandate that water quality criteria must protect designated uses of waters provided for in state law. Designated uses are use goals of a water, whether or not they are being attained.

- When analyzing how water quality criteria protect a designated use, an agency must focus on the population that is exercising that use, and must assess the full extent of that use's goal, where data are available.

The relevant explanatory details for each step of this rationale are presented below. But the underlying structure of the analysis is straightforward and appropriate under and consistent with applicable law.

Another general comment EPA received was that the agency's approach “would impermissibly give tribes in Maine an enhanced status and greater rights with respect to water quality than the rest of Maine's population.” Comments of Janet T. Mills, Maine Attorney General, (page 2). EPA explains below why the analysis EPA presented in its February 2015 decision and the proposal for this action is not only permissible, but also mandated by the CWA as informed by the Indian settlement acts. But as a general matter EPA disagrees that this action is impermissible because it accords the tribes in Maine “greater rights” or somehow derogates the water quality protection provided to the rest of Maine's population.

EPA is addressing the particular sustenance fishing use provided for these tribes under Maine law and ratified by Congress. Because that use is confirmed in provisions in the settlement acts that pertain specifically and uniquely to the Indian tribes in Maine, EPA's analysis of the use and the protection of that use must necessarily focus on how the settlement acts intend for the tribes to be able to use the waters at issue here. However, Maine's claim that EPA is providing tribes in Maine “greater rights” than the general population is incorrect. In this action, EPA is not granting “rights” to anyone. Rather, EPA is simply promulgating Start Printed Page 92476WQS in accordance with the requirements of the CWA—i.e., identifying the designated use for waters in Indian lands, and establishing criteria to protect the target population exercising that use. As explained above, in light of the Indian settlement acts, the designated use is sustenance fishing, the tribes are the target population, and EPA has selected the appropriate FCR of that target population. This approach, together with EPA's selection of 10−6 CRL, is consistent with Maine's approach to protecting the target population in Maine waters outside of Indian lands. EPA's rule provides a comparable level of protection for the target population (sustenance fishers) for the waters in Indian lands that Maine provides to the target population for its fishing designated use (recreational fishers) that applies to waters outside Indian lands.[33] Further, the resulting HHC that EPA is promulgating in this rule protect both non-tribal members and tribal members in Maine. The great majority of the waters subject to the HHC are rivers and streams that are shared in common with non-Indians in the state or that flow into or out of waters outside Indian lands. It is not just the members of the Indian tribes in Maine who will benefit from EPA's action today.

One striking aspect of the comments EPA received on its proposal is that every individual who commented supported EPA's proposed action, including many non-Indians. Nearly all of the comments were individualized expressions of support, ranging from a profound recognition of the need to honor commitments made to the tribes in the Indian settlement acts to an acknowledgement that everyone in Maine benefits from improved water quality. It is notable that the record for this action shows that individuals in Maine who commented did not express concern that the tribes are being accorded a special status or that this action will in any way disadvantage the rest of Maine's population.

As described in section II.B.1, EPA previously approved MIA sections 6207(4) and (9) as an explicit designated use for the inland waters of the reservations of the Southern Tribes and interpreted and approved Maine's designated use of “fishing” for all waters in Indian lands to mean “sustenance fishing.” Several commenters challenged EPA's conclusion that the Indian settlement acts in Maine have the effect of establishing a designated use that includes sustenance fishing. This section explains how the Indian settlement acts provide for the Indian tribes in Maine to fish for their sustenance, and responds to arguments that this conclusion violates the settlement acts. Section III.C explains how EPA, under the CWA, interprets those provisions of state law as a sustenance fishing designated use which must be protected by the WQS applicable to the waters where that use applies.

As explained in more detail in the RTC document, MICSA, MIA, ABMSA, and MSA include different provisions governing sustenance practices, including fishing, depending on the type of Indian lands involved. In the reservations of the Southern Tribes, MIA explicitly reserves to the tribes the right to fish for their individual sustenance.[34] In the trust lands of the Southern Tribes, MIA provides a regulatory framework that requires consideration of “the needs or desires of the tribes to establish fishery practices for the sustenance of the tribes,” among other factors.[35] Congress clearly intended the Northern Tribes to be able to sustain their culture on their trust lands, consistent with Maine law, which amply accommodates a sustenance fishing diet.[36] Therefore, each of these provisions under the settlement acts in its own way is designed to establish a land base for these tribes where they may practice their sustenance lifeways. Indeed, EPA received an opinion from the Solicitor of the United States Department of the Interior (DOI), which analyzed the settlement acts and concluded that the tribes in Maine “have fishing rights connected to the lands set aside for them under federal and state statutes.” [37]

In its February 2015 decision, EPA analyzed how the settlement acts include extensive provisions to confirm and expand the tribes' land base. The legislative record makes it clear that a key purpose behind that land base is to preserve the tribes' culture and support their sustenance practices. MICSA section 5 establishes a trust fund to allow the Southern Tribes and the Maliseets to acquire land to be put into trust. In addition, the Southern Tribes' reservations are confirmed as part of their land base.[38] MICSA combines with MIA sections 6205 and 6205-A to establish a framework for taking land into trust for those three Tribes, and laying out clear ground rules governing any future alienation of that land and the Southern Tribes' reservations. Sections 4(a) and 5 of the ABMSA and section 7204 of the state MSA accomplish essentially the same result for the Micmacs, consistent with the purpose of those statutes to put that tribe in the same position as the Maliseets.

EPA has concluded that one of the overarching purposes of the establishment of this land base for the tribes in Maine was to ensure their continued opportunity to engage in their unique cultural practices to maintain their existence as a traditional culture. An important part of the tribes' traditional culture is their sustenance lifeways. The legislative history for MICSA makes it clear that one critical purpose for assembling the land base for the tribes in Maine was to preserve their culture. The Historical Background in the Senate Report for MICSA opens with the observation that “All three Tribes [Penobscot, Passamaquoddy and Maliseet] are riverine in their land-ownership orientation.” [39] Congress also specifically noted that one purpose of MICSA was to avoid acculturation of the tribes in Maine:

Nothing in the settlement provides for acculturation, nor is it the intent of Congress to disturb the cultural integrity of the Indian people of Maine. To the contrary, the Settlement offers protections against this result being imposed by outside entities by providing for tribal governments which are separate and apart from the towns and cities of the State of Maine and which control all such internal matters. The Settlement also clearly establishes that the Tribes in Maine will continue to be eligible for all federal Indian cultural programs.[40]

As both the Penobscot and Maliseet extensively documented in their comments on this action, their culture relies heavily on sustenance practices, including sustenance fishing. So if a purpose of MICSA is to avoid acculturation and protect the tribes' continued political and cultural existence on their land base, then a key purpose of that land base is to support those sustenance practices.

Several comments dispute that the settlement acts are intended to provide for the tribes' sustenance lifeways, and assert instead that their key purpose was to subject the tribes to the jurisdictional Start Printed Page 92477authority of the state and treat tribal members identically to all citizens in the state. These comments do not dispute the evidence EPA relied on in February 2015 to find that Congress intended to support the continuation of the tribes' traditional culture. Rather, the commenters argue that the overriding purpose of the settlement acts was to impose state law, including state environmental law, on the tribes, which the commenters believe the state could do without regard to the settlement act provisions for sustenance fishing. These assertions reflect an overly narrow interpretation of the settlement acts, and EPA, with a supporting opinion from DOI, has concluded that the settlement acts both provide for the tribes' sustenance lifeways and subject the tribal lands to state environmental regulation. Those two purposes are not inconsistent, but rather support each other. It would be inconsistent for the state to codify provisions for tribal sustenance fishing in one state law, which was congressionally ratified, and then in another state law subject that practice to environmental conditions that render it unsafe.

EPA disagrees with the comment that promulgation of the HHC violates the jurisdictional arrangement in MICSA and MIA. The assertion appears to be that the grant of jurisdiction to the state in the territories of the Indian tribes in Maine means that the tribes must always be subject to the same environmental standards as any other person in Maine. As EPA made clear in its February 2015 decision, the Agency agrees that MICSA grants the state the authority to set WQS in Indian territories. Making that finding, however, does not then lead to the conclusion that the state has unbounded authority to set WQS without regard to the factual circumstances and legal framework that apply to the tribes under both the CWA and the Indian settlement acts. No state has authority or jurisdiction to adopt WQS that do not comply with the requirements of the CWA. The state, like EPA and the tribes, is bound to honor the provisions of the Indian settlement acts. Here, the CWA, as informed by and applied in light of the requirements of the settlement acts, requires that WQS addressing fish consumption in these waters adequately protect the sustenance fishing use applicable to the waters. Because this use applies only to particular waters that pertain to the tribes, the WQS designed to protect the use will necessarily differ from WQS applicable to other waters generally in the state. This result does not violate the grant of jurisdiction to the state. Rather, the state retains the authority to administer the WQS program throughout the state, subject to the same basic requirements to protect designated uses of the waters as are applicable to all states.

EPA also disagrees that promulgation of the HHC violates the so-called savings clauses in MICSA, Pub. L. 96-420, 94 Stat. 1785 sections 6(h) and 16(b), which block the application of federal law in Maine to the extent that law “accords or relates to a special status or right of or to any Indian” or is “for the benefit of Indians” and “would affect or preempt” the application of state law. EPA has consistently been clear that this action does not treat tribes in Maine in a similar manner as a state (TAS) or in any way authorize any tribe in Maine to implement tribal WQS under the federal CWA. Therefore, arguments about whether MICSA blocks the tribes from applying to EPA for TAS under CWA section 518(e) are outside the scope of, and entirely irrelevant to, EPA's promulgation of federal WQS.

Additionally, EPA disagrees that its disapproval of certain WQS in tribal waters and this promulgation will “affect or preempt the application of the laws of the State of Maine” using a federal law that accords a special status to Indians within the meaning of MICSA section 6(h) or a federal law “for the benefit of Indians” within the meaning of section 16(b). With this promulgation, EPA is developing WQS consistent with the requirements of the CWA as applied to the legal framework and factual circumstances created by the Indian settlement acts. EPA here is acting under CWA section 303, which was not adopted “for the benefit of Indians,” but rather sets up a system of cooperative federalism typical of federal environmental statutes, where states are given the lead in establishing environmental requirements for areas under their jurisdiction, but within bounds defined by the CWA and subject to federal oversight. In this case, the Indian settlement acts provide for the tribes to fish for their sustenance in waters in or adjacent to territories set aside for them, which has the effect of establishing a sustenance fishing use in those waters. Because that sustenance fishing use applies in those waters, CWA section 303 requires Maine and EPA to ensure that use is protected. It cannot be the case that the savings clauses in MICSA are intended to block implementation of the Indian settlement acts or MICSA itself.

In the RTC document, EPA addresses in detail the distinctions contained in the Indian settlement acts for the Maine tribes and comments received by EPA on this point. In short, the settlement acts clearly codify a tribal right of sustenance fishing for inland, anadromous, and catadromous fish in the inland waters of the Penobscot Nation's and Passamaquoddy's reservations.[41] EPA approved this right, contained in state law, as an explicit designated use. The Southern Tribes also have trust lands, to which the explicit sustenance fishing right in section 6207 of MIA does not apply, but which are covered by a regulatory regime under MIA that specifically provides for the Southern Tribes to exercise their sustenance fishing practices. The statutory framework for the Northern Tribes' trust lands provides for more direct state regulation of those tribes' fishing practices. Nevertheless, as confirmed by an opinion from the U.S. Department of the Interior,[42] the Northern Tribes' trust lands include sustenance fishing rights appurtenant to those land acquisitions, subject to state regulation. Accordingly, EPA appropriately approved the “fishing” designated use as “sustenance fishing” for all waters in Indian lands.

Tribal representatives and members commented that EPA's promulgation of HHC is consistent with EPA's trust responsibility to the Indian tribes in Maine, and some suggested that EPA's trust relationship with the tribes compels EPA to take this action. Conversely, one commenter argued that this action is not authorized because the federal government has no obligation under the trust responsibility to take this action, and the Indian settlement acts create no specific trust obligation to protect the tribes' ability to fish for their sustenance. These comments raise questions about the nature and extent of the federal trust responsibility to the Indian tribes in Maine and the extent to which the trust is related to this action. EPA agrees that this action is consistent with the United States' general trust responsibility to the tribes in Maine. EPA also agrees that the trust relationship does not create an independent enforceable mandate or specific trust requirement beyond the Agency's obligation to comply with the legal requirements generally applicable to this situation under federal law, in this case the CWA as applied to the circumstances of the tribes in Maine under the settlement acts.Start Printed Page 92478

Consulting with affected tribes before taking an action that affects their interests is one of the cornerstones of the general trust relationship with tribes. EPA has fulfilled this responsibility to the tribes in Maine. EPA has consulted extensively with the tribes to understand their interests in this matter. EPA has also carefully weighed input from the tribes, as it has all the comments the Agency received on this action.

EPA does not agree that the substance of this action is compelled or authorized by the federal trust relationship with the tribes in Maine independent of generally applicable federal law. This action is anchored in two sets of legal requirements: First, the Indian settlement acts, which reserve the tribes' ability to engage in sustenance fishing; second, the CWA, which requires that this use must be protected. The trust responsibility does not enhance or augment these legal requirements, and EPA is not relying on the trust responsibility as a separate legal basis for this action. The Indian settlement acts created a legal framework with respect to these tribes that triggered an analysis under the CWA about how to protect the sustenance fishing use provided for under the settlement acts. This analysis necessarily involves application of EPA's WQS regulations, guidance, and science to yield a result that is specific to these tribes, but each step of the analysis is founded in generally applicable requirements under the CWA, not an independent specific trust mandate.

C. Sustenance Fishing Designated Use

Several commenters challenged EPA's approval, in its February 2015 Decision, of sections 6207(4) and (9) of the MIA as a designated use of sustenance fishing applicable to inland waters of the Southern Tribes' reservations. Several commenters also argued that EPA had no authority to approve Maine's “fishing” designated use with the interpretation that it means “sustenance fishing” for waters in Indian lands. Related to both approvals, the commenters argued that Maine had never adopted a designated use of “sustenance fishing,” thus EPA could not approve such a use, and that EPA did not follow procedures required under the CWA in approving any “sustenance fishing” designated use. EPA disagrees, as discussed in sections III.C.1 and 2.

1. EPA's Approval of Certain Provisions in MIA as a Designated Use of Sustenance Fishing in Reservation Waters.

State laws can operate as WQS when they affect, create or provide for, among other things, a use in particular waters, even when the state has not specifically identified that law as a WQS.[43] EPA has the authority and duty to review and approve or disapprove such a state law as a WQS for CWA purposes, even if the state has not submitted the law to EPA for approval.[44] Indeed, EPA has previously identified and disapproved a Maine law as a “de facto” WQS despite the fact that Maine did not label or present it as such.[45]

The MIA is binding law in the state, and sections 6207(4) and (9) in that law clearly establish a right of sustenance fishing in the inland reservation waters of the Southern Tribes. See Topic 3 of the RTC document for a more detailed discussion. In other words, the state law provides for a particular use in particular waters. It was therefore appropriate for EPA to recognize that state law as a water quality standard, and more specifically, as a designated use. EPA's approval of these MIA provisions as a designated use of sustenance fishing does not create a new federal designated use of tribal “sustenance fishing,” but rather gives effect to a WQS in state law for CWA purposes in the same manner as other state WQS. Furthermore, contrary to commenters' assertions, EPA did not fail to abide by any required procedures before approving the MIA provisions as a designated use. They were a “new” WQS for the purpose of EPA review, because EPA had never previously acted on them. When EPA acts on any state's new or revised WQS, there are no procedures necessary for EPA to undertake prior to approval.[46] The Maine state legislature, which has the authority to adopt designated uses, held extensive hearings reviewing the provisions of the MIA, including those regarding sustenance fishing.

2. EPA's Interpretation and Approval of Maine's “Fishing” Designated Use To Include Sustenance Fishing.

In addition to approving certain provisions of MIA as a designated use in the Southern Tribes' inland reservation waters, EPA also interpreted and approved Maine's designated use of “fishing” to mean “sustenance fishing” for all waters in Indian lands. EPA disagrees with comments that claim that EPA had no authority to do so because EPA had previously approved that use for all waters in Maine without such an interpretation. While EPA approved the “fishing” designated use in 1986 for other state waters, prior to its February 2015 decision, EPA had not approved any of the state's WQS, including the “fishing” designated use, as being applicable to waters in Indian lands.

Under basic principles of federal Indian law, states generally lack civil regulatory jurisdiction within Indian country as defined in 18 U.S.C. 1151.[47] Thus, EPA cannot presume a state has authority to establish WQS or otherwise regulate in Indian country. Instead, a state must demonstrate its jurisdiction, and EPA must determine that the state has made the requisite demonstration and has authority, before a state can implement a program in Indian country. Accordingly, EPA cannot approve a state WQS for a water in Indian lands if it has not first determined that the state has authority to do so.

EPA first determined on February 2, 2015, that Maine has authority to establish WQS for waters in Indian lands. Consistent with the principle articulated above, it is EPA's position that all WQS approvals that occurred prior to this date were limited to state Start Printed Page 92479waters outside of waters in Indian lands. With regard to the “fishing” designated use, Maine submitted revisions to its water quality standards program now codified at 38 M.R.S. section 464-470, to EPA in 1986. This submittal included Maine's designated use of “fishing” for all surface waters in the state. On July 16, 1986, EPA approved most of the revised WQS, including the designated uses for surface waters, without explicit mention of the “fishing” designated use or of the standards' applicability to waters in Indian lands. Maine did not expressly assert its authority to establish WQS in Indian waters until its 2009 WQS submittal, and EPA did not expressly determine that Maine has such authority until February 2015. Therefore, EPA did not approve Maine's designated use of “fishing” to apply in Indian waters in 1986, and EPA's approval of that use for other waters in Maine at that time was not applicable to Indian waters in Maine.

EPA acknowledges the comment that, prior to February 2015, EPA had not previously taken the position that Maine's designated use of “fishing” included a designated use of “sustenance fishing.” As explained herein, it was not until February 2, 2015, that EPA determined that Maine's WQS were applicable to waters in Indian lands, so it was not until then that EPA reviewed Maine's “fishing” designated use for those waters and concluded that, in light of the settlement acts, it must include sustenance fishing as applied to waters in Indian lands.

EPA disagrees with comments that asserted that EPA could not approve the “fishing” designated use as meaning “sustenance fishing” for waters in Indian lands unless EPA first made a determination under CWA section 303(c)(4)(B) that the “fishing” designated use was inconsistent with the CWA. Because EPA had not previously approved the “fishing” designated use for waters in Indian lands, EPA had the duty and authority to act on that use in its February 2015 decision, and was not required to make a determination under CWA section 303(c)(4)(B) before it could interpret and approve the use for waters in Indian lands. Additionally, because the term “fishing” is ambiguous in Maine's WQS, even if EPA had previously approved it for all waters in the state, it is reasonable for EPA to explicitly interpret the use to include sustenance fishing for the waters in Indian lands in light of the Indian settlement acts.[48] This is consistent with EPA's recent actions and positions regarding tribal fishing rights and water quality standards in the State of Washington.[49]

In acting on the “fishing” designated use for waters in Indian lands for the first time, it was reasonable and appropriate for EPA to explicitly interpret and approve the use to include sustenance fishing for the waters in Indian lands. This interpretation harmonized two applicable laws: The provision for sustenance fishing contained in the Indian settlement acts, as explained above in section III.B, and the CWA. Indeed, where an action required of EPA under the CWA implicates another federal statute, such as MICSA, EPA must harmonize the two statutes to the extent possible.[50] This is consistent with circumstances where federal Indian laws are implicated and the Indian canons of statutory construction apply.[51] Because the Indian settlement acts provide for sustenance fishing in waters in Indian lands, and EPA has authority to reasonably interpret state WQS when taking action on them, EPA necessarily interpreted the “fishing” use as “sustenance fishing” for these waters, lest its CWA approval action contradict and, as a practical matter, effectively limit or abrogate the Indian settlement acts (a power that would be beyond EPA's authority).[52] Accordingly, EPA's interpretation of Maine's “fishing” designated use reasonably and appropriately harmonized the intersecting provisions of the CWA and the Indian settlement acts.

Finally, one commenter argued that the settlement acts' provisions for sustenance fishing are merely exceptions to otherwise applicable creel limits and have no implications for the WQS that apply to the waters where the tribes are meant to fish. EPA does not agree with this narrow interpretation of the relationship between the provisions for tribal sustenance practices on the one hand and water quality on the other. Fundamentally, the tribes' ability to take fish for their sustenance under the settlement acts would be rendered meaningless if it were not supported under the CWA by water quality sufficient to ensure that tribal members can safely eat the fish for their own sustenance.

When Congress identifies and provides for a particular purpose or use of specific Indian lands, it is reasonable and supported by precedent for an agency to consider whether its actions have an impact on a tribe's exercise of that purpose or use and to ensure through exercise of its authorities that its actions protect that purpose or use. For example, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals recently determined that the right of tribes in the State of Washington to fish for their subsistence in their “usual and accustomed” places necessarily included the right to an adequate supply of fish, despite the absence of any explicit language in the applicable treaties to that effect.[53] Specifically, the Court held that “the Tribes' right of access to their usual and accustomed fishing places would be worthless without harvestable fish.” [54] Similarly, it would defeat the purpose of MIA, MICSA, MSA, and ABMSA for the Start Printed Page 92480tribes in Maine to be deprived of the ability to safely consume fish from their waters at sustenance levels. Consistent with this case law, the Department of the Interior provided EPA with a legal opinion which concludes that “fundamental, long-standing tenets of federal Indian law support the interpretation of tribal fishing rights to include the right to sufficient water quality to effectuate the fishing right.” [55] If EPA were to ignore the impact that water quality, and specifically water quality standards under the CWA, could have on the tribes' ability to safely engage in their sustenance fishing practices on their lands, the Agency would be contradicting the clear purpose for which Congress ratified the settlement acts in Maine and provided for the establishment of Indian lands in the state. Therefore, it is incumbent upon EPA when applying the requirements of the CWA to harmonize those requirements with this Congressional purpose.

D. Human Health Criteria for Toxics for Waters in Indian Lands

1. Target Population