2014-00624. Certification of Compliance With Meal Requirements for the National School Lunch Program Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Correction

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 2761

AGENCY:

Food and Nutrition Service, USDA.

ACTION:

Final rule; correction.

SUMMARY:

The Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), published a final rule in the Federal Register on January 3, 2014 (79 FR 325), concerning necessary changes made to the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) to conform to requirements contained in the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. This document corrects/replaces an appendix that was added at the end of the rule that offered a detailed Regulatory Impact Analysis. All other information in this rule remains unchanged.

DATES:

Effective date: This correction is effective March 2, 2014.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Julie Brewer, Chief, Policy and Program Development Branch, Child Nutrition Division, FNS, 3101 Park Center Drive, Alexandria, Virginia 22302.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Accordingly, the final rule (FR Doc. 2013-31433) published at 79 FR 325 on January 3, 2014 is corrected as follows:

1. On pages 330 through 340, correct Appendix A to read as follows:

Note:

The following appendix will not appear in the Code of Federal Regulations.

Appendix A—Regulatory Impact Analysis

Agency: Food and Nutrition Service.

Title: Certification of Compliance with Meal Requirements for the National School Lunch Program under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010.

Nature of Action: Final Rule.

Need for Action: Section 201 of the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 provides for a 6 cent per lunch performance-based reimbursement to SFAs that comply with the National School Lunch program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP) meal standards that took effect on July 1, 2012. This rule finalizes the interim rule's regulatory framework for establishing initial school food authority (SFA) compliance with the new meal standards and for monitoring ongoing compliance. In addition, the final rule makes minor changes to the interim rule that are intended to facilitate the certification of SFA compliance with the meal patterns.

Affected Parties: The programs affected by this rule are the NSLP and the SBP. The parties affected by this regulation are local school food authorities, State education agencies and the USDA.

Contents

I. Background

II. Need for Action

III. Key Provisions of the Interim Rule

IV. Key Provisions of the Final Rule

V. Addressing Comments on the Interim Rule and RIA

A. Concerns about State Administrative Costs

B. Concerns about Certification Costs

VI. Cost/Benefit Assessment

A. Final Rule

1. Benefits

2. Costs and Transfers

B. Updated Analysis of Interim Rule Effects

1. Methodology

2. Administrative costs

3. Uncertainties

4. Benefits

5. Transfers

VII. Alternatives

VIII. Accounting Statement

I. Background

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) is available to over 50 million children each school day; an average of 31.6 million children per day ate a reimbursable lunch in fiscal year (FY) 2012. Schools that participate in NSLP receive Federal reimbursement and USDA Foods (donated commodities) for meals that meet program requirements.

Sections 4 and 11 of the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (NSLA) govern the Federal reimbursement of school lunches. Reimbursement for school breakfasts is governed by Section 4(b) of the Child Nutrition Act. Reimbursement rates for both NSLP and SBP meals are adjusted annually for inflation under terms specified in Section 11 of the NSLA.

Federal reimbursement for program meals and the value of USDA Foods totaled $14.9 billion in FY 2012. Table 1 summarizes FNS projections of reimbursable meals served and the value of Federal reimbursements and USDA Foods through FY 2017.

The baseline for this analysis is the cost estimate published with the interim final rule.[1]

Start Printed Page 2762Table 1—Projected Number of Meals Served and Total Federal Program Costs 2

[In billions]

Fiscal year 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 NSLP: Lunches Served 5.3 5.4 5.4 5.4 5.5 Program Cost $12.3 $12.6 $12.7 $12.9 $13.0 SBP: Breakfasts Served 2.3 2.4 2.4 2.5 2.5 Program Cost $3.6 $3.8 $4.0 $4.1 $4.2 Table 2 provides additional detail on the components of the school year (SY) 2012-2013 Federal reimbursement rates for lunches and breakfasts that meet program requirements. The figures in Table 2 exclude the 6 cents for meals that comply with the new meal patterns.

Table 2—Federal Per-Meal Reimbursement and Minimum Value of USDA Foods, SY 2012-2013

Breakfast reimbursement Lunch reimbursement Minimum value of donated foods Section 4(b) of Child Nutrition Act Section 4 NSLA Section 11 NSLA Combined reimbursement, NSLA Sections 4 & 11 Additional Federal assistance for each NSLP lunch served Schools in “Severe Need” Schools not in “Severe Need” SFAs that serve fewer than 60% of lunches free or at reduced price SFAs that serve at least 60% of lunches free or at reduced price SFAs that serve fewer than 60% of lunches free or at reduced price SFAs that serve at least 60% of lunches free or at reduced price Contiguous States: Free $1.85 $1.55 $0.27 $0.29 $2.59 $2.86 $2.88 $0.2275 Reduced Price 1.55 1.25 0.27 0.29 2.19 2.46 2.48 0.2275 Paid 0.27 0.27 0.27 0.29 n.a. 0.27 0.29 0.2275 Alaska: Free 2.97 2.48 0.44 0.46 4.19 4.63 4.65 0.2275 Reduced Price 2.67 2.18 0.44 0.46 3.79 4.23 4.25 0.2275 Paid 0.41 0.41 0.44 0.46 n.a. 0.44 0.46 0.2275 Hawaii: Free 2.16 1.81 0.32 0.34 3.03 3.35 3.37 0.2275 Reduced Price 1.86 1.51 0.32 0.34 2.63 2.95 2.97 0.2275 Paid 0.31 0.31 0.32 0.34 n.a. 0.32 0.34 0.2275 II. Need for Action

Section 201 of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA) directs the USDA to issue regulations to update the NSLP and SBP meal patterns to align them with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). The Department published a proposed rule in January 2011.[3] A final rule was published on January 26, 2012.[4] The new standards took effect on July 1, 2012, the start of SY 2012-2013.

HHFKA Section 201 also provides for a 6 cent increase to the USDA reimbursement for lunches served on or after October 1, 2012 that meet the new meal standards. The interim rule provided the regulatory structure necessary to establish initial school food authority (SFA) compliance with the new meal standards and to monitor ongoing compliance. This final rule responds to concerns raised by comments given in response to the interim rule.

III. Key Provisions of the Interim Rule

The interim rule included provisions that govern initial certification of SFA compliance with the breakfast and lunch meal patterns that took effect on July 1, 2012, ongoing monitoring of compliance by State agencies, consequences for non-compliance, and administrative responsibilities of SFAs and State agencies. SFAs began receiving an additional 6 cents for each reimbursable lunch served on or after October 1, 2012 that was determined to comply with the new meal standards. Key provisions of the interim rule included:

- Defining compliance: SFAs must be compliant with breakfast and lunch meal pattern requirements to receive the performance-based 6 cent lunch reimbursement. All meal components must be present in appropriate quantities. The meals offered to students must also comply with sodium, calorie, saturated fat, and trans fat standards.

- Initial certification of SFA eligibility for performance-based lunch reimbursement: SFAs may be certified Start Printed Page 2763eligible for the performance-based lunch reimbursement in one of several ways. Procedures for submitting certification documentation will be developed by State agencies. Final certification decisions will also be made by State agencies. However, standards for certification and the materials used in the certification process will be developed by FNS and specified in guidance. The interim rule provided for the following certification methods:

i. Nutrient analysis: SFAs may submit to their State agency one week of each menu used by the SFA, along with the results of a nutrient analysis on each menu, and a menu worksheet.

ii. Practices and indicators documentation: SFAs may submit to their State agency responses to a series of questions on program operations, a week of each menu used by the SFA, and a menu worksheet.

iii. State agency reviews: SFAs may be certified in the process of a normal State agency administrative review. An SFA determined by the State agency to be compliant with all meal pattern and nutrient standards during an administrative review will be certified eligible for the performance-based lunch reimbursement.

- Ongoing compliance: SFAs must be held compliant with meal pattern and nutrient standards at subsequent State administrative reviews to remain eligible for the performance-based lunch reimbursement.

- Consequences of non-compliance: SFAs that are determined non-compliant with meal pattern or nutrient standards, either through State review of the SFAs' initial certification materials, or in an initial or future State administrative review, will not be eligible (or will lose eligibility) for the performance-based lunch reimbursement. State agencies that find SFAs to be non-compliant with meal pattern or nutrient standards must provide technical assistance and encourage SFA corrective action and re-application for certification.

- State agency validation reviews: State agencies must perform on-site validation reviews of a 25 percent random sample of certified SFAs during SY 2012-2013. Each validation review can substitute for an administrative review that the State agency would otherwise have to perform during SY 2012-2013.

- Federal assistance to State agencies: HHFKA Section 201 provided $50 million in each of the fiscal years 2012 and 2013 to assist States with training, technical assistance, certification, and oversight. As provided by HHFKA, the preamble to the interim rule specified that $3 million would be retained for Federal administration and $47 million would be distributed to the States in each of these 2 years.

IV. Key Provisions of the Final Rule

This rule finalizes the provisions of the interim rule, including the procedures for performance-based certifications, required documentation and timeframes, validation reviews, compliance and administrative reviews, reporting and recordkeeping, and technical assistance, with a few revisions:

- This final rule amends the reporting requirement at 7 CFR 210.5(d)(2)(ii) to require that State agencies only include in their quarterly SFA performance-based certification report the total number of SFAs in the State and the names of certified SFAs. This represents a simplification of the reporting requirement from the interim rule. The change formalizes the simplification previously adopted by USDA and communicated to State agencies through Policy Memo SP 31-2012.

- This final rule at 7 CFR 210.7(d)(1) makes permanent a flexibility in requirements for weekly maximum grains and meat/meat alternates as originally outlined in Policy Memo SP 26-2013 and the flexibility for serving frozen fruit with added sugar as originally outlined in Policy Memo SP 20-2012. These changes make it easier for SFAs to meet the requirements of the school meals rule, which is a prerequisite for certification for the performance-based reimbursement.

V. Addressing Comments on the Interim Rule and RIA

The interim rule generated about 200 comments. As noted in the preamble to the final rule, most of the comments pertained to either the school meals rule (e.g., commented on the new meal patterns) or to statutory requirements as set forth in HHFKA (e.g., commented on whether 6 additional cents are sufficient to cover the costs of the new meal patterns). As this RIA does not address the school meals rule and as FNS has no discretion to change the statutory requirements of the rule, this RIA will not address those comments.

A. Concerns About State Administrative Costs

A few comments raised concerns about the cost of the States' quarterly reporting requirement on SFA certification. These comments viewed the reporting requirements as overly burdensome.

In response to these concerns, FNS decreased the amount of information required from States in the quarterly report, as noted above. This change decreases the estimated time it takes one State to prepare and submit a quarterly certification report from one hour under the interim rule to 15 minutes under this final rule. These reports will no longer be required once all SFAs have been certified to receive the performance-based reimbursement.

B. Concerns About Certification Costs

A few comments raised concerns about State or SFA administrative costs to comply with the certification process and with a lack of adequate guidance and training of State agency officials by FNS. Other comments indicated that small SFAs do not have the staff resources, computers, or computer skills necessary to develop compliant menus or to complete the certification process. Some comments questioned whether the additional administrative costs are worth the additional 6 cent reimbursement, and they raised concerns about SFAs' abilities to meet certification requirements in a timely manner.

As noted in the preamble, FNS is encouraged by the number of SFAs that have already completed the certification process successfully. In October 2013, State agencies reported that, as of the end of June 2013, approximately 80 percent of all SFAs participating in the NSLP had submitted certification documentation to their respective State agency for review and certification, with more expected by the end of the school year. In addition, 90 percent of all lunches served in May 2013 received the extra 6 cent reimbursement.

With regard to the training provided to State agencies by FNS, we note that FNS led in-person training sessions with every State agency to assist them with the task of helping SFAs navigate the certification process. FNS also developed webinars, spreadsheet tools, documentation, and other training resources to assist State agencies and SFAs. All of these resources remain available on the FNS Web site.[5] The spreadsheet tools, in particular, are intended to assist SFAs that may not have the time or resources to develop or purchase their own software.[6] FNS Start Printed Page 2764recognizes, however, that some SFAs may continue to have difficulty with the process despite these resources. FNS is committed to assisting those SFAs, and the State agency staff who are working with them, by answering additional questions on the certification process as we receive them. FNS also encourages the States to provide additional assistance to SFAs that have not yet submitted requests for certification.

The final rule does not, however, change the requirements in the certification process. Consequently, we also make no fundamental change in the RIA concerning the costs of certification, although we do provide updated estimates of the cost of the interim rule based on the most recent data available. Nevertheless, we note that the other major change between the interim and final rule (i.e., making permanent the flexibility for weekly maximum grains and meat/meat alternates as original outlined in Policy Memo SP 26-2013 and the flexibility for serving frozen fruit with added sugar as originally outlined in Policy Memo SP 20-2012) should make it easier for SFAs to comply with the school meals rule (a prerequisite to becoming certified), though this does not change the certification process itself. As discussed in the preamble and below in Section VI.A.1., we do not find that making permanent these flexibilities negatively impacts the nutritional profile of NSLP meals.

VI. Cost/Benefit Assessment

A. Final Rule

1. Benefits

The impact analysis for the interim rule [7] (and updated below) estimated that full compliance with the new meal patterns would increase SFA revenues by more than $300 million per year in the aggregate, as a result of increased transfers from the Federal government because of the performance-based reimbursement. Although this transfer from the Federal government to SFAs may be viewed as a transfer between members of society and not a direct benefit to society, the increased SFA revenues are expected to speed full SFA compliance with the new meal patterns, which likely offer a wide range of health benefits, as described in the final meal patterns rule.[8]

The changes contained in the final rule are expected to facilitate compliance with the meal patterns, allowing SFAs to take full advantage of the additional revenue that the interim final rule made available. Granting some flexibility on meat, grains, and frozen fruit is an effort by USDA to work with schools that are making serious efforts to comply with the rule's standards but are having some difficulty finding products that have been resized or reformulated specifically to meet the requirements of the rule. To the extent that a little flexibility at the margins encourages schools to plan menus that meet the new standards, students benefit from receiving meals that comply with the new standards rather than receiving meals that do not comply with the new standards.

The benefits to children who consume school meals that follow DGA recommendations are detailed in the impact analysis prepared for the final meal patterns rule.[9] As discussed in that document, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee emphasizes the importance of a diet consistent with DGA recommendations as a contributing factor to overall health and a reduced risk of chronic disease.[10]

The link between poor diets and health problems such as childhood obesity are a matter of particular policy concern given their significant social and economic costs. Obesity has become a major public health concern in the U.S., second only to physical activity among the top 10 leading health indicators in the United States Healthy People 2020 goals. According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008, 34 percent of the U.S. adult population is obese and an additional 34 percent are overweight.[11]

The trend towards obesity is also evident among children; 33 percent of U.S. children and adolescents are now considered overweight or obese,[12] with current childhood obesity rates four times higher in children ages 6 to 11 than they were in the early 1960s (19 vs. 4 percent), and three times higher (17 vs. 5 percent) for adolescents ages 12 to 19.[13] These increases are shared across all socio-economic classes, regions of the country, and have affected all major racial and ethnic groups.[14]

Excess body weight has long been demonstrated to have health, social, psychological, and economic consequences for affected adults.[15] Recent research has also demonstrated that excess body weight has negative impacts for obese and overweight children. Research focused specifically on the effects of obesity in children indicates that obese children feel they are less capable, both socially and athletically, less attractive, and less worthwhile than their non-obese counterparts.[16]

Further, there are direct economic costs due to childhood obesity; $237.6 million (in 2005 dollars) in inpatient costs,[17] and annual prescription drug, emergency room, and outpatient costs of $14.1 billion.[18]

Childhood obesity has also been linked to cardiovascular disease in children as well as in adults. Freeman, Dietz, Srinivasan, and Berenson found that “compared with other children, overweight children were 9.7 times as likely to have 2 [cardiovascular] risk factors and 43.5 times as likely to have 3 risk factors” (p. 1179) and concluded that “[b]ecause overweight is associated Start Printed Page 2765with various risk factors even among young children, it is possible that the successful prevention and treatment of obesity in childhood could reduce the adult incidence of cardiovascular disease” (p. 1175).[19] It is known that overweight children have a 70 percent chance of being obese or overweight as adults. However, the actual causes of obesity have proven elusive.[20] While the relationship between obesity and poor dietary choices cannot be explained by any one cause, there is general agreement that reducing total calorie intake is helpful in preventing or delaying the onset of excess weight gain.

There is some recent evidence that food standards are associated with an improvement in children's dietary quality:

- Taber, Chriqui, and Chaloupka compared calorie and nutrient intakes for California high school students—with food standards in place—to calorie and nutrient intakes for high school students in 14 States with no food standards.[21] They concluded that California high school students consumed fewer calories, less fat, and less sugar at school than students in other States. Their analysis “suggested that California students did not compensate for consuming less within school by consuming more elsewhere” (p. 455). The consumption of fewer calories in school `suggests that competitive standards “. . . may be a method of reducing adolescent weight gain” (p. 456).

- A study of competitive food policies in Connecticut concluded that “removing low nutrition items from schools decreased students' consumption with no compensatory increase at home.” [22]

- Similarly, researchers for Healthy Eating Research and Bridging the Gap found that “[t]he best evidence available indicates that policies on snack foods and beverages sold in school impact children's diets and their risk for obesity. Strong policies that prohibit or restrict the sale of unhealthy competitive foods and drinks in schools are associated with lower proportions of overweight or obese students, or lower rates of increase in student BMI.” [23]

Pew Health Group and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation researchers noted that the prevalence of children who are overweight or obese has more than tripled in the past three decades,[24] which is of particular concern because of the health problems associated with obesity. In particular, researchers found an increasing number of children are being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure. These researchers further observed that children with low socioeconomic status and black and Hispanic children are at a higher risk of experiencing one or more of these illnesses (pp. 39-40, 56). Their analysis also noted that: [T]here is a strong data link between diet and the risk for these chronic diseases. Given the relationship between childhood obesity, calorie consumption, and the development of chronic disease risk factors at a young age, this report proposes that a national policy could alter childhood and future chronic disease risk factors by reducing access to certain energy-dense foods in schools. To the extent that the national policy results in increases in students' total dietary intake of healthy foods and reductions in the intake of low-nutrient, energy-dense foods, it is likely to have a beneficial effect on the risk of these diseases. However, the magnitude of this effect would be proportional to the degree of change in students' total dietary intake, and this factor is uncertain (p. 68).

In summary, the most current, comprehensive, and systematic review of existing scientific research concluded that foods standards can have a positive impact on reducing the risk for obesity-related chronic diseases. Because the factors that contribute both to overall food consumption and to obesity are so complex, FNS has not been able to define a level of disease or cost reduction that is attributable to the changes in foods resulting from implementation of this rule. USDA is unaware of any comprehensive data allowing accurate predictions of the effect of increasing the flexibility in meeting certain dietary requirements by SFA's to certify compliance for the National program and subsequent changes in consumer choice and, especially among children.

Some researchers have suggested possible negative consequences of regulating nutrition content in school foods. They argue that not allowing access to low nutrient, high calorie snack foods in schools may result in overconsumption of those same foods outside the school setting (although as noted earlier, Taber, Chriqui, and Chaloupka concluded overcompensation was not evident among the California high school students in their sample).

The new meal patterns are intended not only to improve the quality of meals consumed at school, but to encourage healthy eating habits generally. Those goals of the meal patterns rule are furthered to the extent that this rule contributes to full compliance with the meal patterns by all SFAs.

The changes adopted in the final rule (summarized in Section IV) are intended to facilitate SFA compliance with the meal pattern requirements and reduce State agency reporting and recordkeeping burden. By making permanent the flexibility on weekly maximum servings of grains and meat/meat alternates, and by allowing frozen fruit with added sugar to credit toward the meal pattern requirement for fruit, the final rule will make it easier for some SFAs to plan menus that comply with the meal pattern requirements.[25]

The added flexibility on weekly maximum servings of grains and meat/meat alternates will benefit SFAs who may continue to rely on prepared foods or recipes that ensure compliance with daily and weekly minimum required quantities of servings of grains and meat/meat alternates but may exceed weekly maximum limits on servings of grains and meat/meat alternates in some weeks. However, because the meal patterns' weekly calorie requirements remain in place, the added flexibility on grains and meat/meat alternates is unlikely to have a significant effect on the overall quantity of food served, the Start Printed Page 2766cost of acquiring that food, or the nutritional profiles of the meals served.

Allowing frozen fruit with added sugar to credit toward the meal patterns' fruit requirement also provides SFAs greater flexibility in purchasing foods for use in the school meal programs. Permitting schools to make use of a wider range of currently available frozen fruit products may reduce the administrative costs of finding and acquiring compliant foods for use in the meal programs. But, like the grains and meat/meat alternate provision, because the calorie limits are still in place, allowing added sugar in frozen fruit products will not undermine the updated nutrition standards.[26]

It is important to emphasize that menus developed by SFAs that are certified eligible for the additional 6 cent reimbursement must meet all of the minimum food group requirements contained in the final school meals rule, whether or not those SFAs take advantage of the added flexibilities of this rule. In addition, all SFAs are held to the same maximum calorie standards contained in the final school meals rule. Those standards are not meal-based. Instead, SFA compliance with the food group standards is assessed by comparing the weighted average amounts served across all meals served per day or in an entire week. Children in SFAs that are certified compliant under the modified standards of this rule will be served meals that satisfy the same minimum requirements as meals served in SFAs that were certified compliant under the original terms of the final school meals rule. Even in the absence of the flexibility added by this rule, the amount of meat and grains served in individual meals will vary significantly from the weighted average minimum and maximum amounts required over the course of a day or week. The changes in this rule recognize that additional flexibility on the upper end of the required range for meat and grains allows SFAs to use products that were formulated prior to the final school meal rule standards and to satisfy student demand. This rule does not offer SFAs a way to reduce the minimum amounts served from any of the food groups emphasized by the final school meal rule. And because this rule does not modify the final school meal rule's maximum calorie requirements, the new flexibility is limited and does not weaken the school meal standards' focus on childhood obesity.[27]

The final school meal rule establishes a primarily food-based set of requirements; these are designed to comply with the recommendations of the DGAs regarding the consumption of a variety of foods from key food groups. The school meal rule sets just a handful of macronutrient standards (for calories, saturated fat, sodium, and trans fat). The changes contained in this rule require SFAs to serve meals that satisfy the same minimum requirements from each of the food groups identified in the final school meal rule without relaxing any of that rule's macronutrient standards. In short, this rule's additional flexibility, designed to make it marginally easier to meet compliance with the new meal standards.

Schools that adopt healthier food standards for their school lunch programs will improve the dietary intake for children at school and make it more likely that those students will have improved health outcomes. However, by allowing greater flexibility in meeting the school lunch dietary standards, it may be that some compliant SFAs relax their implementation of those guidelines somewhat.

USDA has not quantified what changes may result to the overall nutritional content of SFAs availing themselves of those flexibility provisions. There are relatively few SFAs (relative to the total number of SFAs complying with school lunch dietary guidelines) that would significantly change the dietary composition of their school lunch program one way or the other. Those two effects (described above) are offsetting and so the net effects of these changes on the benefits to school children are likely to be marginal relative to the overall benefits afforded by the dietary standards.

Because of the macronutrient requirement is not adjusted, any resulting changes to the nutritional quality of the NSLP and SBP meals served by SFAs are expected to marginal, and so there would likely be few changes to the benefits to children relative to the final school meal rule or to the interim rule on certification for the 6 cent reimbursement.

2. Costs and Transfers

The baseline for our estimate of the cost of the final rule is the estimate for the interim final rule, which we update below using the latest President's Budget projections and preliminary data on certifications for the performance-based reimbursement.

The provisions in the final rule will likely result in a small increase in cost to the Federal Government (as a result of a transfer of Federal funds in the form of additional performance-based reimbursements to a small number of schools receiving the performance-based reimbursement that might have otherwise not received it), though we expect this potential increase to fall within the cost range estimated for the interim final rule, as updated below.

The effect of the provisions in the final rule (i.e. increased flexibility on grains, meats, and frozen fruits with added sugar) is to reduce the costs of compliance for the small minority of SFAs that would otherwise not have been certified compliant with the new meal standards by the end of SY 2013-2014. The policy memos issued by FNS in September 2012 and February 2013 had already extended these provisions through the end of SY 2013-2014.

These provisions are essentially administrative efficiency measures that will reduce meal pattern compliance costs at the margin for some SFAs; the provisions are not expected to have a significant effect on food costs. Since these provisions are options (not requirements) [28] and because we have no data on how many schools might avail themselves of either of these options, we do not estimate those cost savings in this analysis.

Given the assumptions (explained in more detail elsewhere in this analysis) about a phased certification process for some SFAs, the estimated cost of Federal performance-based Start Printed Page 2767reimbursements (and the value of additional SFA revenue) is $1.54 billion through FY 2017 (1 percent less than the $1.55 billion estimated with full implementation).

To the extent that additional flexibilities are afforded to SFAs, this rule could result in marginally lower costs to SFAs relative to the interim final rule baseline. USDA has not quantified those changes as there are relatively few SFAs (relative to the total number of SFAs complying with school lunch dietary guidelines) that would significantly change the dietary composition of their school lunch program one way or the other.

The added flexibility on weekly maximum servings of grains and meat/meat alternates could benefit SFAs who may continue to rely on prepared foods or recipes that ensure compliance with daily and weekly minimum quantities but may exceed weekly maximums in some weeks. That provision may reduce the administrative costs of meal planning for some SFAs, and may reduce the costs associated with modifying recipes or finding new prepared foods in the market with slightly different formulations than products currently purchased.

Because the flexibility on grains, meat/meat alternates, and frozen fruit had previously been extended by FNS through SY 2013-2014, the effect of these provisions on the initial certification of SFAs for the performance-based reimbursement is expected to be very small. Administrative data on certifications approved or pending through May 2013 indicate that only a small minority of SFAs are likely to remain uncertified by the end of SY 2013-2014. For those SFAs, these provisions may help reduce the costs of certification after that time.[29] For all other SFAs, these provisions will make it marginally easier to maintain compliance with daily and weekly meal pattern requirements, a necessary condition for continued receipt of the performance-based reimbursement. We expect these provisions to generate a small but uncertain cost savings for SFAs through a small reduction in SFA compliance costs.

The rule also finalizes the change in State agency quarterly reporting requirement on SFA certification. That change, previously adopted through Policy Memo SP-31-2012, reduces quarterly State agency reporting burden to an estimated 15 minutes per quarter per State agency.[30] The last change, contained in the preamble to the final rule, will eliminate the requirement that State agencies submit quarterly reports on SFA certification for the performance-based rate increase once all SFAs have been certified. The administrative savings from this provision is minimal.[31]

B. Updated Analysis of Interim Rule Effects

The analysis provided below updates a similar analysis prepared for the interim rule impact analysis.[32] We update the figures here using data on actual SFA certifications that were not available when the interim rule was published in April 2012, as well as new financial and participation projections provided in the 2014 President's Budget. The data collected since April 2012 allows for a more precise estimate of SFA certifications and receipt of performance-based reimbursements in FY 2013 and projections for fiscal years 2014 through 2017. This analysis is presented for the information of those interested in the effects of the rule on SFAs, State agencies and USDA. It provides estimates of the economic impact of the rule overall, not just the incremental effects of the final rule.

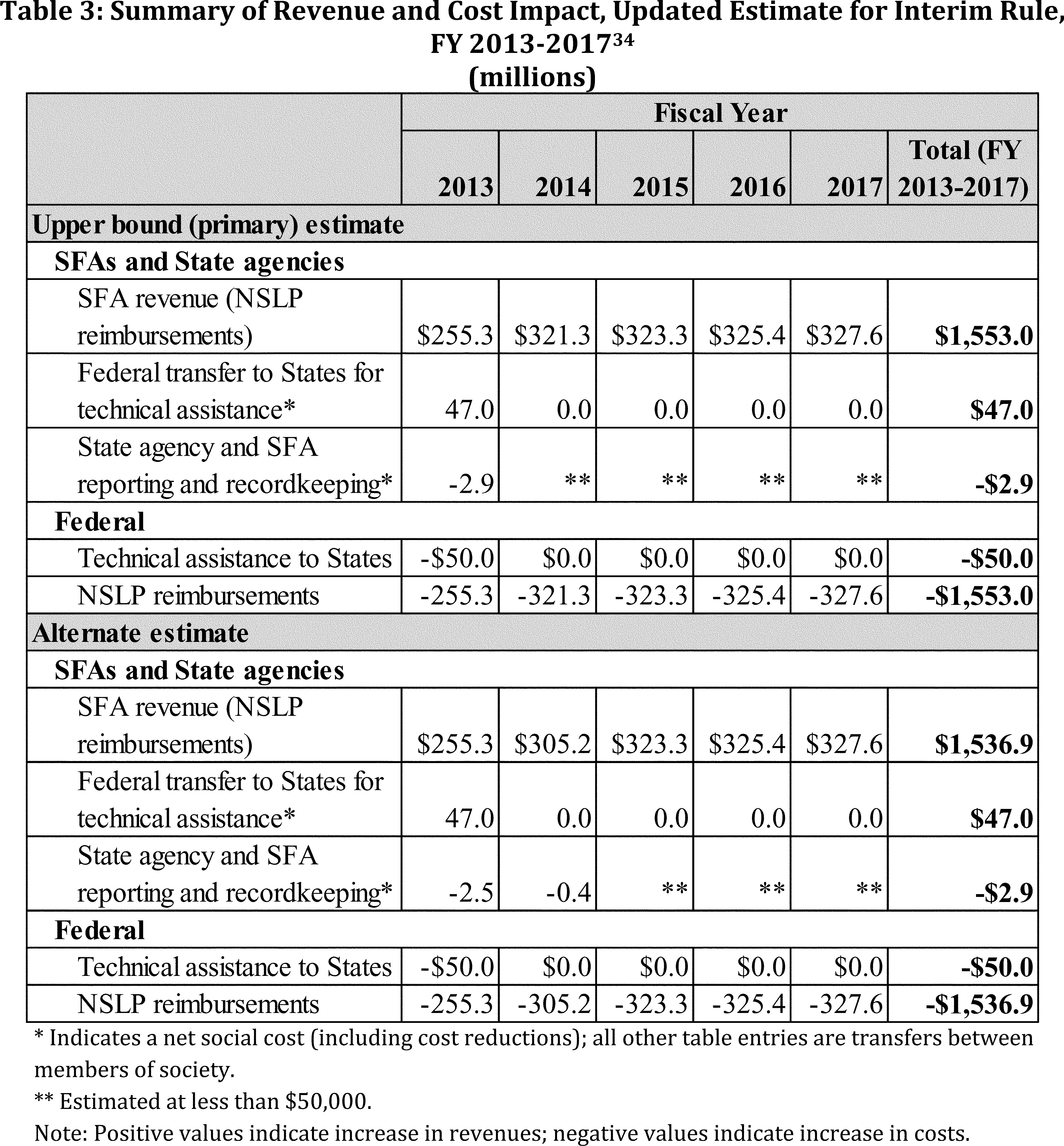

In Table 3, two estimates are provided in recognition of the uncertainty of how quickly SFAs will be determined compliant with the new meal standards and, therefore, how soon they will be eligible for the performance-based rate increase. Data available as of October 2013 shows that 73% of meals served in FY2013 have been certified for the performance-based reimbursement as of July 2013, with 90% of meals served in May 2013 certified as of July 2013. Given the rate of retroactive certification of SFAs and meals, our upper bound (and also primary) estimate assumes that all SFAs will be certified by the end of FY 2013 and that 80% of the lunches served in FY 2013 will eventually be certified to receive the additional 6 cent reimbursement.

As of October 2013, administrative data that indicate that 80 percent of SFAs had been certified or had submitted certification documentation to their respective State agency for review and certification by the end of June 2013. It assumes that the remaining 20 percent of SFAs will be certified (or certified retroactively) in the remaining months of the fiscal year. Administrative data also indicate that 90 percent of meals served in May 2013 qualified for the extra 6 cent reimbursement, and that many SFAs are being certified retroactively as the processing of applications and approval of certification requests catch up with SFAs' documented compliance with the new meal patterns.[33]

Our alternate scenario relies on administrative data on certifications through the first several months of SY 2012-2013 to estimate the revenues and costs of a phased implementation that assumes full compliance during FY 2014. For both estimates, we assume that 80% of the meals served in FY 2013 will qualify for the additional 6 cent reimbursement; in the alternate estimate, we assume 95% of meals will qualify in FY 2014, and 100% will qualify in FY 2015 and beyond. In addition, in this second scenario we assume that roughly 90 percent of SFAs will be found compliant by the end of FY 2013, or certified compliant retroactively to the start of FY 2014. We further assume that the remaining 10% of SFAs will be certified sometime during FY 2014, and that 95% of FY 2014 lunch reimbursements will include the performance-based 6 cents. We assume that 100 percent of SFAs (and, consequently, 100 percent of meals) will be certified to receive the performance-based reimbursement in FY 2015 and beyond.

Start Printed Page 27681. Methodology

The estimated increase in the Federal cost of NSLP reimbursements is a straightforward calculation of the number of meals that are certified in compliance with the new meal standards times 6 cents (adjusted for inflation). This approach applies the additional 6 cents to USDA's baseline projection of lunches. The 6 cents is subject to the same inflation adjustment applied to the Section 4 and Section 11 components of the lunch reimbursement, rounded down to the nearest cent.[35] The interim rule inflates the 6 cents separately from the Section 4 or Section 11 rates. Given our projected increase in the CPI Food Away from Home, we estimate that the 6 cents will remain unchanged through FY 2017.[36]

Full Implementation by October 1, 2013

If all SFAs are certified for the performance-based 6 cent lunch rate increase as of October 1, 2013 (as assumed in the primary estimate), then the Federal cost and SFA revenue increase from FY 2013 through FY 2017 Start Printed Page 2769would total about $1.55 billion. This upper bound estimate (our primary estimate) assumes full compliance with the new breakfast and lunch meal patterns' food group and nutrient requirements by the start of (or retroactive to the start of) SY 2013-2014.

The added revenue will be distributed across SFAs in proportion to the number of reimbursable lunches served. Because students eligible for free or reduced-price meals participate in the school meals programs at higher rates than other students, revenue per enrolled student will tend to be higher in SFAs with the greatest percentage of free and reduced-price certified students. However, eligibility for free or reduced price meals is not the only factor that impacts student participation in the NSLP. Other factors that vary by SFA include the distribution of students by grade level, prices charged for paid lunches, availability of offer vs. serve (in elementary and middle schools), the variety of entrees offered, and school geography.[37]

The data available do not allow us to account for each of those variables here. Instead we estimate in Table 4 the distribution of revenue across SFAs under the assumption that revenue is proportional to enrollment.[38]

Start Printed Page 2770Phased Implementation Within 2 Years

As we note above, State agencies reported in October 2013 that more than 80 percent of all SFAs participating in the NSLP had submitted certification documentation to their respective State agency for review and certification by the end of June 2013, and that 90 percent of meals qualified for the higher reimbursement in May. Administrative data also show that many SFAs are being certified retroactively as the processing of applications and approval of certification requests catch up with SFAs' documented compliance with the new meal patterns. Consequently, we feel comfortable assuming for this alternate analysis that roughly 90 percent of SFAs will be found compliant by the end of FY 2013, or certified compliant retroactively to the start of FY 2014.

We further assume that the remaining 10% of SFAs will be certified sometime during FY 2014, and that 95% of FY 2014 lunch reimbursements will include the performance-based 6 cents. We assume that 100 percent of SFAs Start Printed Page 2771(and, consequently, 100 percent of meals) will be certified to receive the performance-based reimbursement in FY 2015 and beyond.

Given these assumptions about a phased certification process for some SFAs, the estimated cost of Federal performance-based reimbursements (and the value of additional SFA revenue) is $1.54 billion through FY 2017 (1 percent less than the $1.55 billion estimated with full, immediate implementation).

2. Administrative Costs

Our updated estimate of administrative costs differs only slightly from the estimate published with the interim final rule.[40] The only change is a slight shifting in when certification expenses were incurred (or are estimated to be incurred), based on administrative data on certifications received after publication of the interim rule, as well as accounting for additional wage inflation.

As most SFAs submitted documentary materials in FY 2012 or FY 2013, most of the cost of this administrative burden was realized in those years, and we note that FY 2012 has been excluded from this formal cost analysis. States reported 23.4 percent of SFAs were certified to receive the performance-based reimbursement for October 2012 and therefore incurred certification costs in FY 2012. For purposes of our primary analysis, we assume that the remaining 76.6 percent did so by the end of FY 2013 (as described above, we currently only have data through June 2013).

Based on this updated information on when certifications occurred, we estimate in our primary estimate that State agency and SFA administrative costs associated with the rule totaled $3.7 million across FY 2012 and FY 2013 if all SFAs were determined compliant with the new meal standards based on an initial submission of SFA documentation. $2.9 million of these costs were realized in FY 2013 and are therefore included in the tables above. The ongoing burden created by reporting and recordkeeping requirements are not expected to be appreciably higher than they were before the implementation of the interim rule.

Under our alternate scenario, we assume that an additional 66.6 percent of SFAs submitted documentation by the end of FY 2013 and that the remaining 10 percent of SFAs did not submit applications to their State agencies in FY 2013.[41] For this estimate, we assume that these SFAs will take the steps necessary to reach compliance in FY 2014, and will submit documentation to their State agencies in that fiscal year, so those certification costs for both the States and remaining SFAs are realized in FY 2014.

Administrative costs will be similar, but will be spread over two years under our alternate scenario of less than 100 percent SFA compliance with the new standards by the start of SY 2013-2014. The cost of preparing and processing initial certification claims in FY 2012 and FY 2013 by 90 percent of SFAs will equal $3.4 million, of which $2.5 million was realized in FY 2013. The cost of submitting and processing the remaining claims will equal $0.4 million in FY 2014.

Due to inflation, SFAs and State agencies that submit or process documentation in FY 2014 will face slightly higher labor costs than those that submitted documentation in prior fiscal years, though this cost increase is too small to appear in our tables at the level of detail presented.

3. Uncertainties

The most significant unknown in this analysis is the length of time it will take all SFAs to reach full compliance. Our primary revenue and cost estimate developed in the previous section assumes full compliance by October 2013.[42] Our alternate estimate assumes that 10 percent of SFAs are certified compliant with the rule sometime in FY 2014.

Because the economic effects are essentially proportionate to the level of SFA compliance, the effects of more or less optimistic scenarios can be estimated by scaling the effects of our alternate scenario upward or downward by the assumed rates of initial and future year compliance.

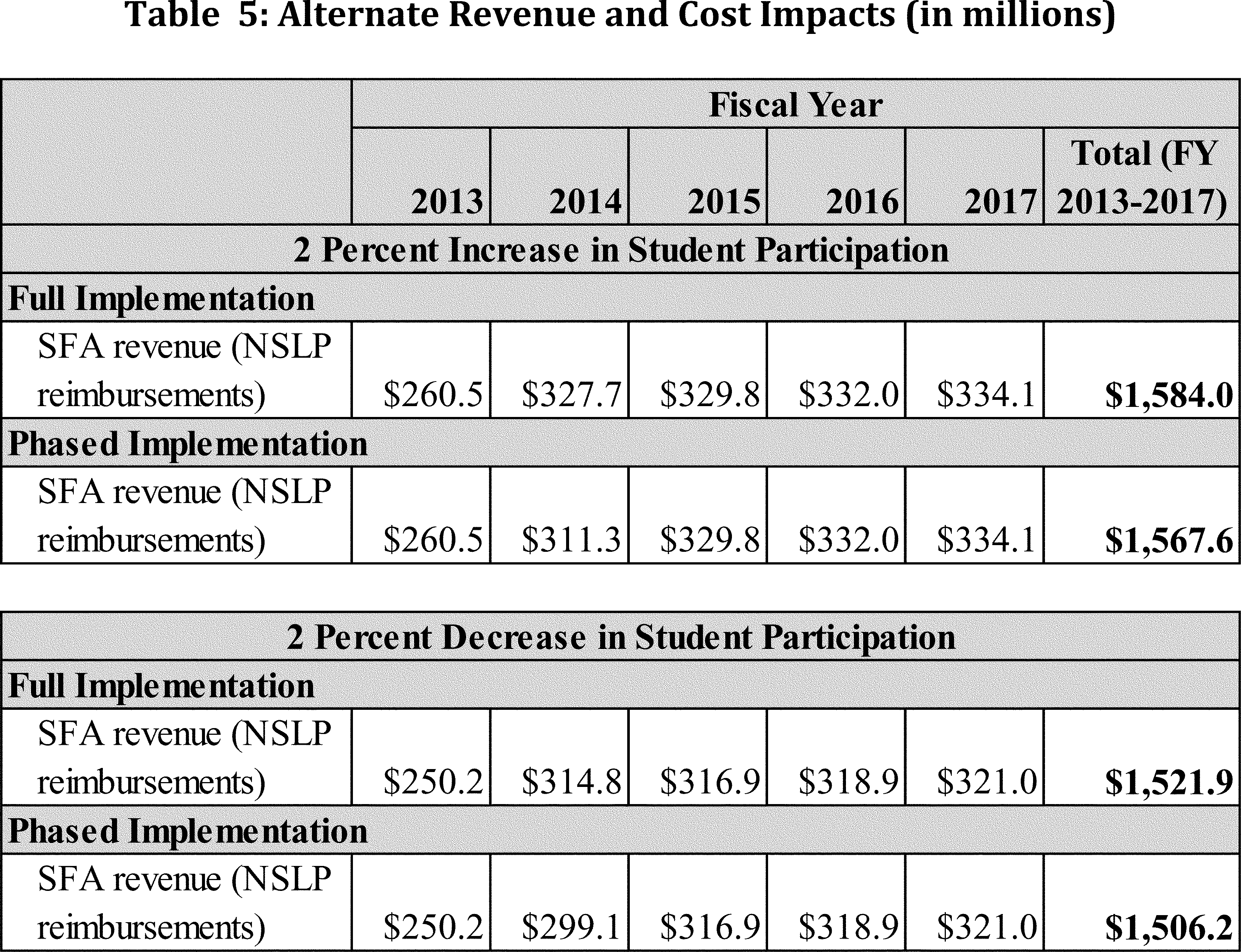

Another important unknown is the student response to the introduction of new meal patterns. Although the introduction of healthier meals may attract new participants to the school meals program, the replacement or reformulation of some favorite foods on current school menus may depress participation, at least initially. As we did in the impact analysis for the school meal patterns rule, we provide alternate estimates given a 2 percent increase and a 2 percent decrease in student participation. The estimates shown here are simply 2 percent higher (or lower) than our estimates in Table 3. That is, we estimate the effect of changes in student participation on the value of the performance-based rate increase alone.

Changes in participation would also affect the current Section 4 and Section 11 reimbursements and student payments for paid and reduced price lunches. Because those effects are not a consequence of the 6 cent rate increase, but rather a consequence to the change in the content of the meals served, we exclude them from Table 5.

Table 5 does not show the effects on administrative costs (reporting and recordkeeping by State agencies and SFAs, and the technical assistance funds transferred by the Federal government to the States). Those are unchanged from Table 3.

Start Printed Page 27724. Benefits

The benefits to children who consume school meals that follow DGA recommendations is detailed in the impact analysis prepared for the final meal patterns rule.[43] As discussed in that document, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee emphasizes the importance of a diet consistent with DGA recommendations as a contributing factor to overall health and a reduced risk of chronic disease.[44] The new meal patterns are intended not only to improve the quality of meals consumed at school, but to encourage healthy eating habits generally. Those goals of the meal patterns rule are furthered by the funding made available by this final rule.

5. Transfers

The interim rule will result in a transfer from the Federal government to SFAs of as much as $1.55 billion through FY 2017 to implement the new breakfast and lunch meal patterns that took effect on July 1, 2012. The Federal cost is fully offset by an identical benefit to SFAs and State agencies.

The interim rule generates significant additional revenue for SFAs that partially offset the additional food and labor costs to implement the improved meal standards more fully aligned with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. For example, USDA previously estimated that the improved meal standards would cost an additional $1,220.2 million in FY 2015 (the first year in which the new standards are fully implemented).[45] The rule will generate $323.3 million in additional SFA revenue in the same fiscal year, helping school districts cover about 26% of this additional cost. USDA has also estimated that the paid lunch pricing and non-program food revenue provisions of HHFKA sections 205 and 206 will generate $7.5 billion in revenue for SFAs through FY 2015.[46] In the aggregate, therefore, these provisions provide a net gain in SFA revenue that exceeds the estimated cost of serving school meals that follow the Dietary Guidelines.

VII. Alternatives

The substantive differences between the interim and final rules are:

1. Decreasing the amount of information required in the States' quarterly certification reports and clarifying that the reports need not be submitted once all SFAs are certified for the performance-based reimbursement; and

2. Making permanent the increased flexibility for SFAs regarding weekly maximum grains and meat/meat alternates and the serving of frozen fruit with added sugar.

These changes all decrease the administrative and/or compliance burden on States and SFAs and/or increase the flexibility for SFAs in serving lunches and breakfasts that comply with the school meal patterns, thereby decreasing costs to States and SFAs. The primary alternative considered in the course of developing the final rule was not to make these changes.

We do not provide a separate cost estimate for this “doing nothing” alternative because the decrease in burden associated with the shorter quarterly reports for States is small [47] (less than $50,000 per year) and because Start Printed Page 2773the additional transfers possibly attributable to the increase in flexibility to SFAs are likely within the cost estimate range published with the interim rule [48] and updated above.

VIII. Accounting Statement

As required by OMB Circular A-4 (available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/regulatory_matters_pdf/a-4.pdf), we have prepared an accounting statement showing the annualized estimates of benefits, costs and transfers associated with the provisions of this final rule.

The figures in the accounting statement are the estimated discounted, annualized costs and transfers of the rule. The figures are computed from the nominal 5-year estimates developed above and summarized in Table 3. The accounting statement contains figures computed with 7 percent and 3 percent discount rates for both our upper bound (primary) estimate and our alternate estimate.

Note that we only provide an accounting statement for the final rule, not for the interim rule (as the interim rule was the baseline for our cost analysis for the final rule). As noted in the above analysis, any possible changes in costs or transfers attributed to the final rule are small and are likely within the cost estimate range published with the interim rule and updated above.

Illustration of Computation

The annualized value of this discounted cost stream over FY 2013-2017 is computed with the following formula, where PV is the discounted present value of the cost stream, i is the discount rate (e.g., 7 percent), and n is the number of years (5): [49]

Start SignatureEstimate Year dollar Discount rate % Period covered Benefits Qualitative: Compared with the interim rule, the final rule makes permanent the increased flexibility for SFAs regarding weekly maximum grains and meat/meat alternates and the serving of frozen fruit with added sugar. If the greater flexibility leads to more SFA participation in the reimbursable school meals program, then students' health may improve. Costs Annualized Monetized ($millions/year) n.a. 2013 7 FY 2013-2017. n.a. 2013 3 As discussed in Section V.A., the reduction in administrative costs to State agencies as a result of the reduced quarterly reporting requirement on SFA compliance is already in the range estimated for our baseline. The reduction in burden for State agencies who will no longer have to submit quarterly reports on SFA compliance once all SFAs have been certified is minimal. The final rule may also slightly reduce the costs of complying with the meal patterns for some SFAs, and reduce the costs of maintaining compliance by others. This reduction in SFA cost is not estimated, and likely lies within our range of alternate estimates for the interim rule. Transfers Annualized Monetized ($millions/year) n.a. 2013 7 FY 2013-2017. n.a. 2013 3 The changes in the final rule that are designed to facilitate compliance with the new meal patterns are expected to increase slightly the number of SFAs that are certified by their State agencies to receive the additional 6 cents per reimbursable lunch. This increased transfer from the Federal government to SFAs will be realized after the end of SY 2013-2014 (primarily in FY 2014 and beyond) when the grains, meat/meat alternate, and frozen fruit provisions contained in FNS policy memos would have expired in the absence of the rule. This possible, small increase in Federal transfers to SFAs also likely lies within our range of alternate estimates for the interim rule. End Signature End Supplemental InformationDated: January 9, 2014.

Audrey Rowe,

Administrator, Food and Nutrition Service.

Footnotes

1. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 82 pp. 25024-25036.

Back to Citation2. USDA projections of reimbursable lunches and breakfasts served, and total NSLP and SBP program costs, prepared for the FY 2014 President's Budget. NSLP program cost includes entitlement commodity assistance, but is not adjusted for the projected additional amount necessary to bring total commodity assistance up to 12 percent of the combined value of the Section 4 and 11 reimbursements as required by NSLA section 6(e) (42 U.S.C. 1755(e)). Note that the estimate for the cost of NSLP as given in on p. 175 of the 2014 President's budget appendix does not include estimated entitlement commodity assistance, unlike Table 1. In addition, although the USDA projections in the FY 2014 President's Budget included the cost of the extra 6 cents per meal (and assumed that all meals served would be eligible for the extra 6 cents per meal), the projections presented here do not include the value of the 6 cents—instead, program costs are presented as if no meals receive the 6 cents reimbursement, to provide a basis for comparison for the rest of the estimates in this RIA. The projected number of meals has changed from the estimated projections in the interim rule on account of updated projections provided in the 2014 President's Budget.

Back to Citation3. Federal Register, Vol. 76, No. 9, pp. 2494-2570.

Back to Citation4. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 17, pp. 4088-4167.

Back to Citation5. See http://www.fns.usda.gov/outreach/webinars/child_nutrition.htm and http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Governance/Legislation/certificationofcompliance.htm.

Back to Citation6. Some comments indicated that the FNS-developed spreadsheet tools were difficult to work with. While FNS will not be changing the tool at this time, FNS has conducted several in-person trainings and webinars to assist State agencies and SFA having difficulties using the tools. Additionally, the FNS Web site lists other commercially available tools that SFAs may find more appropriate or helpful.

Back to Citation7. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 82, pp. 25024-25036.

Back to Citation8. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 17, pp. 4088-4167.

Back to Citation9. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 17, pp. 4088-4167.

Back to Citation10. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, p. B1-2. (http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-DGACReport.htm).

Back to Citation11. C.L. Ogden and M.D. Carroll (2010), “Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Extreme Obesity among Adults: United States, Trends 1960-1962 through 2007-2008,” National Center for Health Statistics, June 2010, available online at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf.

Back to Citation12. M.A. Beydoun and Y. Wang (2011), “Socio-demographic disparities in distribution shifts over time in various adiposity measures among American children and adolescents: What changes in prevalence rates could not reveal,” International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 6:21-35, available online at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3005993/.

Back to Citation13. Institute of Medicine (2007), Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity: How do we Measure Up? Committee on Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity, edited by J.P. Koplan, C.T. Liverman, V.I. Kraak, and S.L. Wisham, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 24.

Back to Citation14. S.J. Olshansky, D.J. Passaro, R.C. Hershow, J. Layden, B.A. Carnes, J. Brody, L. Hayflick, R.N. Butler, D.B. Allison, and D.S. Ludwig (2005). “A Potential Decline in Life Expectancy in the United States in the 21st Century,” The New England Journal of Medicine, 352:1138-1145.

Back to Citation15. J. Guthrie, C. Newman, and K. Ralston (2009), “USDA School Meal Programs Face New Challenges,” Choices: The Magazine of Food, Farm, and Resource Issues, 24 (available online at http://www.choicesmagazine.org/magazine/print.php?article=83); and Y. Wang, M.A. Beydoun, L. Liang, B. Cabellero and S.K. Kumanyika (2008), “Will all Americans Become Overweight or Obese? Estimating the Progression and Cost of the US Obesity Epidemic,” Obesity, 16:2323-2330.

Back to Citation16. A. Riazi, S. Shakoor, I. Dundas, C. Eiser, and S.A. McKenzie (2010), “Health-related quality of life in a clinical sample of obese children and adolescents,” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8:134-139.

Back to Citation17. L. Trasande, Y. Liu, G. Fryer, and M. Weitzman (2009), “Trends: Effects of Childhood Obesity on Hospital Care and Costs, 1999-2005,” Health Affairs, 28:w751-w760.

Back to Citation18. J. Cawley (2010), “The Economics of Childhood Obesity,” Health Affairs, 29:364-371, available online at http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/29/3/364.full.pdf.

Back to Citation19. D.S. Freeman, W.H. Dietz, S.R. Srinivasan, and G.S. Berenson (1999), “The Relation of Overweight to Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Children and Adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart Study,” Pediatrics, 103:1175-1182.

Back to Citation20. ASPE, Health & Human Services (No Date), “Childhood Obesity,” Assistant Secretary for Planning and valuation, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, available online at http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/child_obesity.

Back to Citation21. D.R. Taber, J.F. Chriqui, and F.J. Chaloupka (2012), “Differences in Nutrient Intake Associated With State Laws Regarding Fat, Sugar, and Caloric Content of Competitive Foods,” Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine, 166:452-458.

Back to Citation22. M.B. Schwartz, S.A. Novak, and S.S. Fiore (2009), “The Impact of Removing Snacks of Low Nutritional Value from Middle Schools,” Health Education & Behavior, 36:999-1011, p. 999.

Back to Citation23. Healthy Eating Research and Bridging the Gap (2012), “Influence of Competitive Food and Beverage Policies on Children's Diets and Childhood Obesity,” p. 3, available online at http://www.healthyeatingresearch.org/images/stories/her_research_briefs/Competitive_Foods_Issue_Brief_HER_BTG_7-2012.pdf.

Back to Citation24. Pew Health Group and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2012), Heath Impact Assessment: National Nutrition Standards for Snack and a la Carte Foods and Beverages Sold in Schools, available online at http://www.pewhealth.org/uploadedFiles/PHG/Content_Level_Pages/Reports/KS%20HIA_FULL%20Report%20062212_WEB%20FINAL-v2.pdf.

Back to Citation25. As explained in this section and in the preamble to the rule, making permanent this flexibility does not compromise the nutritional profile of school meals. IOM's recommendations were to serve food in minimum amounts subject to maximum calorie limits; the additional flexibility allowed by these provisions is still subject to the maximum calorie limits for school meals.

Back to Citation26. We note that, in SY 2009-2010, frozen fruit accounted for only 17% of the fruit used by U.S. schools. See p. 83 of USDA/FNS, School Food Purchase Study III (2012), available online at http://www.fns.usda.gov/Ora/menu/Published/CNP/FILES/SFSPIII_Final.pdf.

Back to Citation27. The final rule's flexibility on sugar contained in frozen fruit is also constrained by the retention of the interim rule's calorie restrictions. Because the interim rule already allowed for added sugar in canned fruit, the final rule's modification of the frozen fruit standard is primarily a means to widen the selection of processed fruit available to SFAs under nutrient standards that are comparable to the standards already allowed under the interim rule for other processed fruit. In the absence of the final rule provision on frozen fruit with added sugar, SFAs remained free to serve canned fruit in light syrup rather fresh or processed fruit without added sugar.

Back to Citation28. In general, we assume that optional provisions do not increase costs. We make this assumption because SFAs, State agencies, or other affected parties that now have additional options will choose to take advantage of the option if it is advantageous (i.e. cost-saving, more efficient, less burdensome, etc.) for them to do so; if it is not advantageous for them to do so, they do not have to implement the option, and therefore, their costs would not change from our baseline. For these reasons, providing additional options will almost certainly lower costs and/or increase benefits for at least some subset of affected parties and will not increase costs for any party without providing at least offsetting benefits—though we do not attempt to quantify these savings, efficiencies, and benefits, due to the speculative nature of such an estimate.

Back to Citation29. As we note above, approximately 80 percent of SFAs had submitted documentation to their respective State agencies for review and certification as of June 2013. Administrative data also show that many SFAs are being certified retroactively as the processing of applications and approval of certification requests catch up with SFAs' documented compliance with the new meal patterns. With or without the changes contained in the final rule, State agency technical assistance will likely concentrate on this subset of uncertified SFAs during SY 2013-2014. Those efforts are likely to substantially reduce the number of non-certified SFAs by the end of SY 2013-2014. It is that remaining subset of SFAs that may benefit most from the permanent extension of the grains, meat/meat alternate, and frozen fruit policy changes contained in the final rule.

Back to Citation30. Estimate developed for Paperwork Reduction Act reporting and contained in the preamble to the rule. Because this change was already adopted by USDA through a policy memo, the reduction in burden for State agencies is part of our baseline, and the formalization of that policy by the final rule does not further reduce State agency reporting costs.

Back to Citation31. Although the relative burden decrease of 75% seems substantial, the absolute burden decrease (as measured in the dollar value of State agency staff time) is only about $4,000 per year across the entire United States.

Back to Citation32. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 82, pp. 25024-25036.

Back to Citation33. I.e., the number of meals certified for the performance-based reimbursement in the early months of the school year increases with each additional month of administrative data reported by the States.

Back to Citation34. We note that the estimates in this table are largely consistent with the estimates published with the interim rule; the main differences are caused by (1) the exclusion of FY 2012 and the inclusion of FY 2017 in the above table, and (2) a small downward revision in the estimated number of lunches served in future Fiscal Years, resulting in an decrease in estimated Federal transfers to SFAs for reimbursable lunches. We also note that the 2014 President's Budget likely overstates the final number of lunches that will be served in FY 2013, but we use the 2014 President's Budget as our basis of analysis for consistency's sake, both for internal consistency and consistency with past estimates.

Back to Citation35. The fractional cents are not lost; they are added back to the base rate before applying the next year's inflation adjustment.

Back to Citation36. The CPI Food Away From Home Index is the factor specified by NSLA Section 11 to adjust the reimbursement rates for school lunch and breakfast. Our projected values for this index are those prepared by OMB for use in the 2014 President's Budget.

Back to Citation37. School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Stdy-III, Vol. 2, Table IV.2, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. for U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, 2007, available online at http://www.fns.usda.gov/ora/MENU/Published/CNP/cnp.htm.

Back to Citation38. Table 4 is based on SY 2009-2010 data for public local educational agencies (LEAs) from the Common Core of Data, U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/.

Back to Citation39. The distribution of States by Census region was taken from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/us_regdiv.pdf. The territories included here are Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

The urbanicity categories are U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics “urban-centric local codes.” “City” is any territory, regardless of size, that is inside an urbanized area and inside a principal city. “Suburb” is any territory, regardless of size, inside an urbanized area but outside a principal city. “Town” is a territory of any size inside an urban cluster but outside an urbanized area. “Rural” is a Census-defined rural territory outside both an urbanized area and an urban cluster. These definitions are contained in documentation for the SY 2009-2010 Common Core of Data, http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/.

Percent of enrollment certified for free or reduced-price meals is also an NCES Common Core of Data variable.

Back to Citation40. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 82, pp. 25024-25036.

Back to Citation41. Our alternate estimate of Federal reimbursements in Section V.B. assumes that 90 percent of SFAs will be certified compliant by the start of FY 2014, or retroactively back to the start of FY 2014. That allows for the possibility that fewer than 90 percent of SFAs will submit applications for certification before the end of FY 2013. For the sake of simplicity, we assume in the alternative administrative cost section of this analysis that 90 percent of applications for certification are submitted before the end of FY 2013.

Back to Citation42. Note that, even though this RIA was most recently revised in October 2013, data were only available through June 2013.

Back to Citation43. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 17 pp. 4088-4167.

Back to Citation44. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, p. B1-2. (http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-DGACReport.htm).

Back to Citation45. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 17 pp. 4088-4167.

Back to Citation46. USDA estimate contained in the regulatory impact analysis for the interim rule, “National School Lunch Program: School Food account Revenue Amendments Related to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010.” Federal Register Vol. 76, No. 117, pp. 35301-35318.

Back to Citation47. Furthermore, we do not estimate any Federal administrative savings as a result of the shorter quarterly reports.

Back to Citation48. Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 82 pp. 25024-25036.

Back to Citation49. The Excel formula for this is PMT (rate, # periods, PV, 0, 1)

Back to Citation

Document Information

- Published:

- 01/16/2014

- Department:

- Food and Nutrition Service

- Entry Type:

- Rule

- Action:

- Final rule; correction.

- Document Number:

- 2014-00624

- Pages:

- 2761-2773 (13 pages)

- Docket Numbers:

- FNS-2011-0025

- RINs:

- 0584-AE15: Certification of Compliance With Meal Requirements for the National School Lunch Program Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010

- RIN Links:

- https://www.federalregister.gov/regulations/0584-AE15/certification-of-compliance-with-meal-requirements-for-the-national-school-lunch-program-under-the-h

- PDF File:

- 2014-00624.pdf

- CFR: (1)

- 7 CFR 210