2023-28483. Endangered and Threatened Species; Designation of Critical Habitat for the Nassau Grouper

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 126

AGENCY:

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Commerce.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

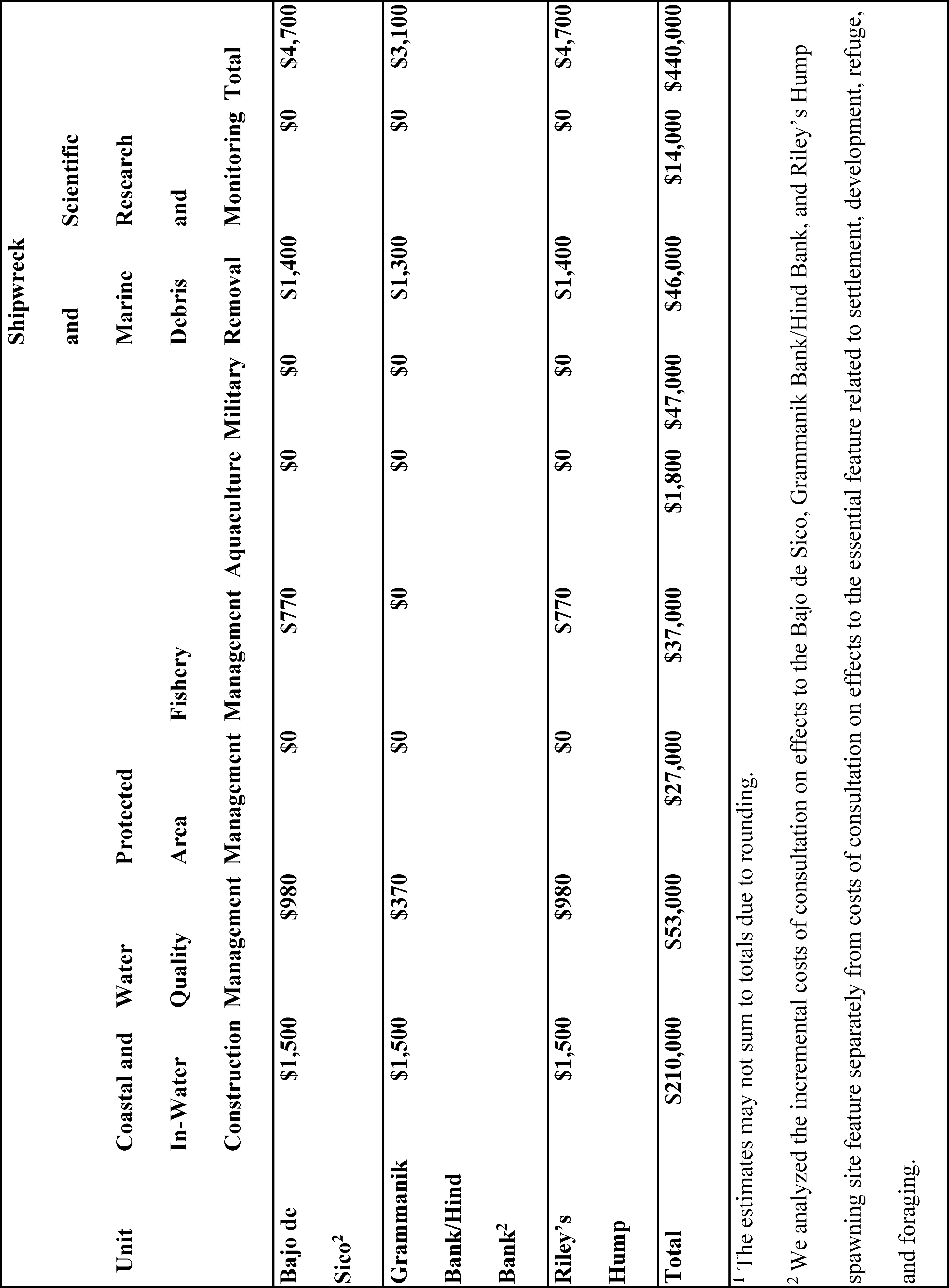

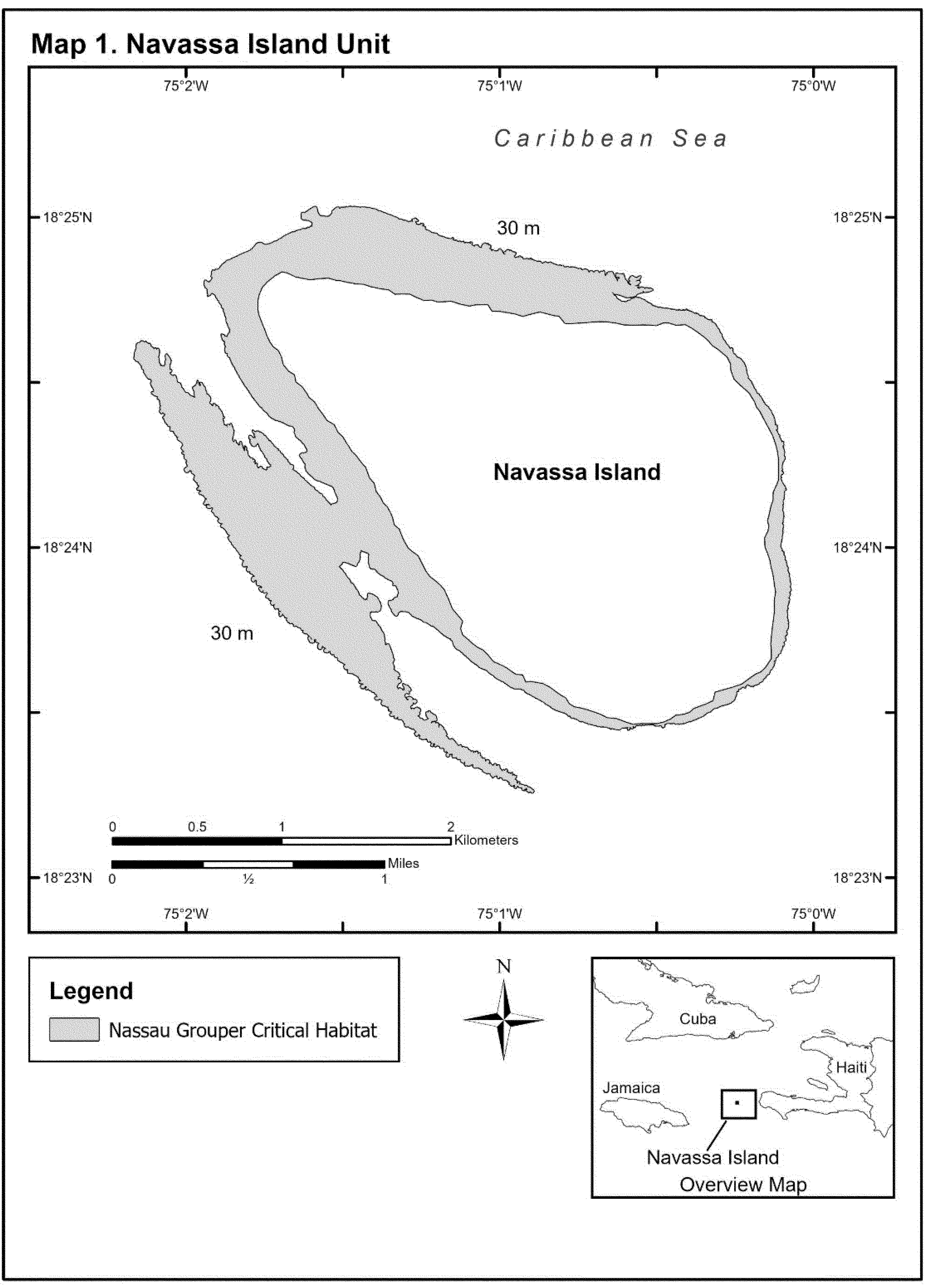

We, NMFS, designate critical habitat for the threatened Nassau grouper ( Epinephelus striatus) pursuant to section 4 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Specific areas designated as critical habitat contain approximately 2,384.67 sq. kilometers (km) (920.73 sq. miles) of aquatic habitat located in waters off the coasts of southeastern Florida, Puerto Rico, Navassa, and the United States Virgin Islands (USVI). We have considered positive and negative economic, national security, and other relevant impacts of the critical habitat designation, as well as all public comments that were received.

DATES:

This rule becomes effective February 1, 2024.

ADDRESSES:

The final rule, maps, Final Regulatory Flexibility Analysis, and Critical Habitat Report used in preparation of this final rule are available on the NMFS website at https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/endangered-species-conservation/critical-habitat. All comments and information received are available at http://www.regulations.gov. All documentation is also available upon request.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Orian Tzadik, NMFS Southeast Region, Orian.Tzadik@noaa.gov, 813–906–0353.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

In accordance with section 4(b)(2) of the ESA and our implementing regulations (50 CFR 424.12), this final rule is based on the best scientific data available concerning the range, biology, habitat, threats to the habitat, and conservation objectives for the Nassau grouper ( Epinephelus striatus). We have reviewed the available data and public comments received on the proposed rule. We used the best data available to identify: (1) features essential to the conservation of the species; (2) the specific areas within the occupied geographical areas that contain the physical essential feature that may require special management considerations or protection; (3) the Federal activities that may impact the critical habitat; and (4) the potential impacts of designating critical habitat for the species. This final rule is based on the biological information and the economic, national security, and other relevant impacts described in the Critical Habitat Report. This supporting document is available online (see ADDRESSES ) or upon request (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT ).

Background

On June 29, 2016, we published a final rule that listed Nassau grouper as a threatened species (81 FR 42268). The listing rule identified fishing at spawning aggregations and inadequate law enforcement as the most serious threats to this species. No critical habitat was designated for the Nassau grouper at that time.

On October 17, 2022, NMFS proposed to designate critical habitat for Nassau grouper within U.S. jurisdictions throughout the range of the species. We requested public comment on the proposed designation and supporting reports during a 60-day comment period, which closed on December 15, 2022 (87 FR 62930). The essential features of the proposed Nassau grouper critical habitat consisted of (1) nearshore to offshore areas necessary for recruitment, development, and growth of Nassau grouper containing a variety of benthic types that provide cover from predators and habitat for prey, and (2) marine sites used for spawning and adjacent waters that support movement and staging associated with spawning. The final rule does not modify the definitions of these essential features but does identify several new areas containing these features. The proposed rule identified 19 specific areas, or units of critical habitat, in waters off the coasts of southeastern Florida, Puerto Rico, Navassa, and the USVI that contain the essential features. The area covered by the Naval Air Station Key West (NASKW) Integrated Natural Resource Management Plan (INRMP) was found to be ineligible for designation pursuant to section 4(a)(3)(B)(i) of the ESA due to the conservation benefits the INRMP affords the Nassau grouper. Pursuant to section 4(b)(2) of the ESA, no areas were proposed for exclusion from the designation on the basis of economic, national security, and other relevant impacts. We did not propose to designate any unoccupied critical habitat.

This final rule relies on the ESA section 4 implementing regulations that are currently in effect, which include provisions that were revised or added in 2019. As explained in the proposed critical habitat rule, on July 5, 2022, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California issued an order vacating the ESA section 4 implementing regulations that were revised or added to 50 CFR part 424 in 2019, which included changes made to the definition of physical or biological feature and the criteria for designating unoccupied critical habitat (“2019 regulations”; 84 FR 45020, August 27, 2019). In the proposed rule, we determined that the critical habitat determination and designation would be the same under the 50 CFR part 424 regulations as they existed before 2019 and under the regulations as revised by the 2019 rule. On September 21, 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit granted a temporary stay of the district court's July 5 order, and on November 14, 2022, the Northern District of California issued an order granting the government's request for voluntary remand without vacating the 2019 regulations. As a result, the 2019 regulations are once again in effect, and we are applying the 2019 regulations here. Following the remand of the 2019 regulations, on June 22, 2023, NMFS and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a proposed rule to revise the ESA section 4 implementing regulations (88 FR 40764). Thus, for purposes of this final rule, we also considered whether our analyses or conclusions would be any different under the regulations in effect prior to 2019 or under the recently proposed regulations (87 FR 62930). We have determined that while our analysis would differ in some respects, the conclusions ultimately reached and presented here would be the same under either set of regulations.

This final rule describes the critical habitat for Nassau grouper in waters off the coasts of Florida, and the U.S. Caribbean ( i.e., waters off the coasts of Navassa Island, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) and the basis for its designation. It summarizes relevant information regarding the biology and habitat use of Nassau grouper; the methods used to develop the critical habitat designation; a summary of, and responses to, public comments received; and the final critical habitat determination. The more detailed analyses that contributed to the conclusions presented in this final rule, including the analysis of areas eligible for designation, can be found in the Critical Habitat Report (NMFS, 2022) Start Printed Page 127 and the Nassau Grouper Biological Report (Hill and Sadovy de Mitcheson, 2013). These supporting documents are referenced throughout this final rule and are available for review (see ADDRESSES ).

Statutory and Regulatory Background for Critical Habitat Designations

Section 3(5)(A) of the ESA defines critical habitat as (i) the specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed, on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protection; and (ii) specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed, upon a determination by the Secretary of Commerce (Secretary) that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. (16 U.S.C. 1532(5)(A)). Conservation is defined in section 3(3) of the ESA as the use of all methods and procedures which are necessary to bring any endangered species or threatened species to the point at which the measures provided pursuant to this Act are no longer necessary (16 U.S.C.1532(3)). Section 3(5)(C) of the ESA provides that, except in those circumstances determined by the Secretary, critical habitat shall not include the entire geographical area which can be occupied by the threatened or endangered species. Our regulations provide that critical habitat shall not be designated within foreign countries or in other areas outside U.S. jurisdiction (50 CFR 424.12(g)).

Section 4(a)(3)(B)(i) of the ESA prohibits designating as critical habitat any lands or other geographical areas owned or controlled by the Department of Defense (DOD) or designated for its use that are subject to an INRMP prepared under section 101 of the Sikes Act (16 U.S.C. 670a) if the Secretary determines in writing that such plan provides a benefit to the species for which critical habitat is designated. Section 4(b)(2) of the ESA requires the Secretary to designate critical habitat for threatened and endangered species under the jurisdiction of the Secretary on the basis of the best scientific data available and after taking into consideration the economic impact, the impact on national security, and any other relevant impact of specifying any particular area as critical habitat. This section also grants the Secretary discretion to exclude any area from critical habitat if the Secretary determines the benefits of such exclusion outweigh the benefits of specifying such area as part of the critical habitat. However, the Secretary may not exclude areas if such exclusion will result in the extinction of the species (16 U.S.C. 1533(b)(2)).

Once critical habitat is designated, section 7(a)(2) of the ESA requires Federal agencies to ensure that actions they authorize, fund, or carry out are not likely to destroy or adversely modify that habitat (16 U.S.C. 1536(a)(2)). This requirement is in addition to the section 7(a)(2) requirement that Federal agencies ensure their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of ESA-listed species. Specifying the geographic area identified as critical habitat also facilitates implementation of section 7(a)(1) of the ESA by identifying areas where Federal agencies can focus their conservation programs and use their authorities to further the purposes of the ESA. See 16 U.S.C. 1536(a)(1). The ESA section 7 consultation requirements do not apply to citizens engaged in actions on private land that do not involve a Federal agency, for example if a private landowner is undertaking an action that does not require a Federal permit or is not federally funded. However, designating critical habitat can help focus the efforts of other, non-federal, conservation partners ( e.g., state and local governments, individuals, and non-governmental organizations).

Species Description

Nassau grouper, Epinephelus striatus (Bloch 1792), are long-lived, moderate-sized fish (family Epinephelidae) with large eyes and a robust body. Their coloration is generally buff, with distinguishing markings of five dark brown vertical bars, a large black saddle blotch on the caudal peduncle ( i.e., the tapered region behind the dorsal and anal fins where the caudal fin attaches to the body), and a row of black spots below and behind each eye. Juveniles exhibit a color pattern similar to adults ( e.g., Silva Lee, 1977). Individuals reach sexual maturity between 4 and 8 years (Sadovy and Colin, 1995; Sadovy and Eklund, 1999). Nassau grouper undergo shifts in habitat utilization as they mature: larvae settle in nearshore habitats and then as juveniles move to nearshore patch reefs (Eggleston, 1995), and eventually recruit to deeper waters and reef habitats (Sadovy and Eklund, 1999). As adults, individuals are sedentary except for when they aggregate to spawn—the timing of which appears to be linked to both lunar cycles and water temperature (Kobara et al., 2013). Maximum age has been estimated as 29 years, based on an ageing study using sagittal otoliths (Bush et al., 2006). Maximum size is about 122 cm total length (TL) and maximum weight is about 25 kg (Heemstra and Randall, 1993).

Natural History and Habitat Use

The Nassau grouper, like most large marine reef fishes, demonstrates a two-part life cycle with pelagic eggs and larvae but demersal juveniles and adults. It undergoes a series of shifts of both habitat and diet as it matures from larval to adult stage. Adults maintain resident home ranges (Randall, 1962 1963; Carter et al., 1994), but may undergo long migrations to spawning aggregation sites (Bolden, 2000). Reproduction is known to occur only during annual aggregations, in which large numbers of Nassau grouper, ranging from dozens to tens of thousands, collectively gather to spawn at predictable times and locations.

In the following sections, we describe the natural history of the Nassau grouper as it relates to habitat needs from the egg and larval stage to settlement into nearshore habitats followed by a progressive offshore movement with increasing size and maturation.

Egg and Larval Planktonic Stage

Fertilized eggs are pelagic, measure about 1 mm in diameter, and have a single oil droplet about 0.22 mm in diameter (Guitart-Manday and Juárez-Fernandez, 1966). Data from eggs produced in an aquarium (Guitart-Manday and Juarez-Fernandez, 1966) and artificially fertilized in the laboratory (Powell and Tucker, 1992; Colin, 1992) indicate that spherical, buoyant eggs hatch 23–40 hours following fertilization. Eggs of groupers that spawn at sea require a salinity of about 30 parts per thousand (ppt) or higher for maximum survivorship and for them to float (Tucker, 1999). Both buoyancy and survivorship decrease as salinity declines below optimum levels, resulting in less than 50% hatching rates at salinities of 24 ppt (Ellis et al., 1997).

The pelagic larvae begin feeding on zooplankton approximately 2–4 days after hatching (Tucker and Woodward, 1994). Newly hatched larvae in the laboratory measured 1.8 mm notochord length and were slightly curved around the yolk sac (Powell and Tucker, 1992). Nassau grouper larvae are rarely reported from offshore waters (Leis, 1987) and little is known of their movements or distribution. The pelagic larval period has been reported to range from 37 to 45 days based on otolith analysis of newly settled juveniles in the Bahamas (Colin et al., 1997) with a mean of 41.6 days calculated from net- Start Printed Page 128 caught samples (Colin, 1992; Colin et al., 1997). Collections of pelagic larvae were made 0.8 to 16 km off Lee Stocking Island, Bahamas, at 2 to 50 m depths and from tidal channels leading onto the Exuma Bank (Greenwood, 1991). Larvae were widely dispersed or distributed in patches of various sizes (Greenwood, 1991). Larvae collected 10 days after back-calculated probable spawning date measure 6–10 mm standard length (SL) and attain a maximum size of 30 mm SL (Shenker et al., 1993).

Larval Settlement

After spending about 40 days in the plankton, in the Bahamas Nassau grouper larvae have been found to recruit from the oceanic environment into demersal, bank habitats through tidal channels (Colin, 1992). This recruitment process can be brief and intense, occurring in short pulses during highly limited periods (often several days) each year, and has been found to be associated with prevailing winds, currents, and lunar phase (Shenker et al., 1993). These late larvae/early juvenile Nassau grouper (18–30 mm total length (TL)) moved inshore from pelagic environments to shallower nursery habitats (Shenker et al., 1993).

Most of what is known about the earliest cryptic life stages is known from research in the Bahamas where recently settled Nassau grouper were found to be on average 32 mm TL when they recruit into the nearshore habitat and settle out of the plankton (Eggleston, 1995). Newly settled or post-settlement fish found by Eggleston (1995) ranged in size from 25–35 mm TL and were patchily distributed at 2–3 m depth in substrates characterized by numerous sponges and stony corals with some holes and ledges residing exclusively within coral clumps ( e.g., Porites spp.) covered by masses of macroalgae (primarily the red alga Laurencia spp.). Stony corals provided attachment sites for red algae since direct holdfast attachment was probably inhibited by heavy layers of coarse calcareous sand. This algal and coral matrix also supported high densities and a diverse group of xanthid crabs, hippolytid shrimp, bivalve, gastropods and other small potential prey items. In the USVI, Beets and Hixon (1994) observed groupers on a series of nearshore artificial reefs constructed of cement blocks with small and large openings and found the smallest Nassau groupers (30–80 mm TL) were closely associated with the substrate, usually in small burrows under the concrete blocks. Growth during this period was about 10 mm/month (Eggleston, 1995).

Juveniles

After settlement, Nassau grouper grow through three juvenile stages, defined by size, as they progressively move from nearshore areas adjacent to the coastline to shallow hardbottom areas and seagrass habitat. The size ranges for the three juvenile stages, which we discuss in more detail below, are approximations and are not always collected the same way between studies. Juvenile Nassau grouper reside within nearshore areas for about 1 to 2 years, where they are found associated with structure in both seagrass (Eggleston, 1995; Camp et al., 2013; Claydon and Kroetz, 2008; Claydon et al., 2009, 2010; Green, 2017) and hardbottom areas (Bardach, 1958; Beets and Hixon, 1994; Eggleston, 1995; Camp et al., 2013; Green, 2017). Juvenile Nassau grouper leave these refuges to forage and when they transition to new habitats (Eggleston, 1995; Eggleston et al., 1998).

Newly Settled (Post-Settlement) Juveniles (~2.5–5 cm TL)

Most of what is known about the earliest demersal life stages of Nassau grouper comes from a series of studies conducted from 1987–1994 near Lee Stocking Island in the Exuma Cays, Bahamas as reported by Eggleston (1995). These surveys and experiments in mangrove-lined lagoons and tidal creeks (1–4 m deep), seagrass beds, and sand or patch reef habitats helped identify the Nassau grouper's early life ontogenetic ( i.e., developmental) habitat changes. Benthic habitat of newly settled Nassau grouper (31.7 ± 2.9 mm TL (mean ± standard deviation), n=31) was described as exclusively within coral clumps ( e.g., Porites spp.) covered by masses of macroalgae (primarily the red alga Laurencia spp.). These macroalgal clumps were patchily distributed at 2 to 3 m depths in substrate characterized by numerous sponges and stony corals, with some holes and ledges. The stony corals (primarily Porites spp.) provided attachment sites for red algae; direct holdfast attachment to the coral by the red algae was probably inhibited by heavy layers of coarse calcareous sand and minor amounts of silt and detritus. The open lattice of the algal-covered coral clumps provided cover and prey and facilitated the movement of individuals within the interstices of the clumps (Eggleston 1995). Post-settlement Nassau grouper were either solitary or aggregated within isolated coral clumps. Density of the post-settlement fish was greatest in areas with both algal cover and physical structure (Eggleston, 1995). A concurrent survey of the adjacent seagrass beds found abundance of nearly settled Nassau grouper was substantially higher in Laurencia spp. Habitats than in neighboring seagrass (Eggleston, 1995).

Eggleston (1995) found the functional relationship between percent algal cover and post-settlement density of Nassau grouper was linear and positive compared to other habitat characteristics such as algal displacement volume, and the numbers of holes, ledges, and corals. Recently-settled Nassau grouper have also been collected from tilefish ( Malacanthus plumieri) rubble mounds, with as many as three fish together (Colin et al., 1997). They have been reported as associated with discarded queen conch ( Strombus gigas) shells and other debris within Thalassia beds (Claydon et al., 2009, 2010) in the Turks and Caicos Islands, although the exact fish sizes observed are not clear. Post-settlement survival in macroalgal habitats is higher than in seagrass beds, showing a likely adaptive advantage for the demonstrated habitat selection (Dahlgren and Eggleston, 2000). Nassau grouper remain in the shallow nearshore habitat for about 3 to 5 months following settlement and grow at about 10 mm/month (Randall, 1983; Eggleston, 1995).

Early Juveniles (~4.5–15 cm TL)

Band transects performed near Lee Stocking Island, Bahamas, 4–5 months after the settlement period (June 1991–93) showed that early juveniles (8.5 ± 11.7 cm TL, n=65) demonstrated a subtle change in microhabitat; 88 percent were solitary within or adjacent to algal-covered coral clumps (Eggleston, 1991). As the early juveniles grew, reef habitats, including solution holes and ledges, took on comparatively greater importance as habitats (Eggleston, 1991). Low habitat complexity was associated with increased predation rates and lowered the survival of recruits (Dahlgren and Eggleston, 2000).

Early juveniles in the Bahamas have a disproportionately high association with the macroalgae Laurencia spp.; whereas other microhabitats ( e.g., seagrass, corals) are used in proportion to their availability (Dahlgren and Eggleston, 2001). Reports from Mona Island, Puerto Rico (Aguilar-Perera et al., 2006) indicate that early juveniles (60–120 mm TL) were found at the edge of a seagrass patch, under rocks surrounded by seagrass, in a tire, and in a dissolution hole in shallow bedrock.

A conspicuous change in habitat occurs about 4–5 months post-settlement when Nassau grouper move Start Printed Page 129 from nearshore macroalgae habitat to adjacent patch reefs located within either seagrass or hardbottom areas, between the nearshore environment and the offshore reefs. In the Bahamas, early juvenile Nassau grouper (12–15 cm TL) exhibited an ontogenetic movement from macroalgal clumps to patch reef habitats in the late summer and early fall after settlement in the winter as demonstrated by a significant decrease in juvenile density within the macroalgal habitat and concomitant increase in the seagrass meadows (Eggleston, 1995). Similarly in the Turks and Caicos, 87 percent of early juvenile Nassau grouper (identified as less than 12 cm TL, n=181) were found in seagrass and 10 percent were found in rock or rubble habitat (Claydon and Kroetz, 2008). Within the Turks and Caicos seagrass habitat, 44 percent of the early juveniles were found in discarded conch shells and 33 percent were found along blowout ledges (Claydon and Kroetz, 2008). Individuals were rarely seen in open areas; instead they were usually seen in close proximity to a structure or sheltering within structure ( i.e., discarded conch shell or blowout ledge). Density of Nassau grouper (>12 cm TL) was found to increase when discarded conch shells were placed in seagrass habitat (Claydon et al., 2009), perhaps due to reduced mortality as the structure limited access of larger predators (Claydon et al,. 2010). On shallow constructed block reefs in the USVI, newly settled and early juveniles (3–8 cm TL) occupied small separate burrows beneath the reef while larger juveniles occupied holes in the reefs (Beets and Hixon, 1994).

Juvenile fish are vulnerable to predation (large fish, eels, other groupers and sharks) and utilize refuges to protect themselves (Beets and Hixon, 1994; Eggleston 1995; Claydon and Kroetz, 2008) and to forage for crustaceans using ambush predation techniques (Eggleston et al., 1998; Claydon and Kroetz, 2008). Juveniles often associate with refuges proportional to their body size (Beets and Hixon, 1994) and seek new shelter as they grow (Eggleston, 1995). Suitable refuges provide some protection from predation; however, juveniles may leave their refuges to forage for food and during ontogenetic shifts in habitat (Eggleston, 1995).

Late Juveniles (~15–50cm TL)

Camp et al. (2013) conducted a broad-scale survey in the shallow nearshore lagoons of Little Cayman and found Nassau grouper (12–26 cm TL) on hardbottom areas more frequently than other more available habitats (sand, seagrass and algae). Eighty-two percent of juvenile Nassau grouper (18.4 ± 3.4 cm TL, n=142) were found at depths from 1.0–2.3 m in hardbottom habitat that provided crevices, holes, ledges and other shelter, with 10–66 percent of the holes with grouper also containing one or more cleaning organisms ( i.e., banded coral shrimp; Elacatinus gobies; or bluehead wrasse, Thalasoma bifasciatum). A small percentage of Nassau grouper (3 percent) were found in other habitat sheltered in holes ( i.e., concrete blocks or conch shells). Overall, the vast majority of juvenile Nassau grouper were associated with some form of shelter, suggesting that shelter represents a primary determinant of microhabitat use (Camp et al., 2013).

As late juveniles, Nassau grouper may occupy seagrass habitats for food and protection from predators (Claydon and Kroetz, 2008); they forage for crustaceans in seagrass beds (Eggleston et al., 1998). In a survey of seagrass bays in the USVI, Green (2017) found that juvenile Nassau grouper (n=46, 6–30 cm TL) were more abundant in areas with taller canopy and less dense native seagrasses compared to higher density of the same seagrasses and low canopy height. Differences in abundance were attributed to the taller canopy providing better cover from predators (Beets and Hixon, 1994). Tall seagrass also increases hiding places for their prey (Eggleston, 1995), and the less dense seagrass habitats permit better movement by Nassau grouper to forage (Green, 2017).

Juvenile Nassau grouper also rely on hardbottom structure for refuge from predation and ambush of potential prey. Nassau grouper residing on patch reefs use short bursts of speed that allow them to ambush crabs located up to 7 m away from a patch reef and return to a reef within 5 seconds (D. Eggleston pers. comm. as cited in Eggleston et al., 1999). Suitable refuges provide cover for juvenile Nassau grouper with crevices, holes, and ledges proportionate to their body size (Beets and Hixon, 1994).

As juveniles grow, they move progressively to deeper banks and offshore reefs (Tucker et al., 1993; Colin et al. 1997). In Bermuda, Bardach (1958) noted that few small Nassau grouper (less than 4 inches or 10 cm TL) were found on outer reefs, and few mature fish were found on inshore reefs. The weights of mature individuals trapped in deep areas were about double that of Nassau grouper captured in the shallow areas. While there can be an overlap of adults and juveniles in hardbottom habitat areas, size segregation generally occurs by depth, with smaller fish typically occurring in shallow inshore waters (3 to 17 m), and larger individuals more commonly occurring on deeper (18 to 55 m), offshore banks (Bardach et al., 1958; Cervigón, 1966; Silva Lee, 1974; Radakov et al., 1975; Thompson and Munro, 1978).

Adults

Both male and female Nassau grouper typically mature between 40 and 45 cm SL (44 and 50 cm TL), with most individuals attaining sexual maturity by about 50 cm SL (55 cm TL) and about 4–5 years of age (see Table 1 and additional details in Hill and Sadovy de Mitcheson, 2013) and with most fish spawning by age 7+ years (Bush et al., 2006).

Adults are found near shallow, high-relief coral reefs and rocky bottoms to a depth of at least 90 m (Bannerot, 1984; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). Reports from fishing activities in the Leeward Islands show that although Nassau grouper were fished to 130 m, the greatest trap catches were from 52–60 m (Brownell and Rainey, 1971). In Venezuela, Nassau grouper were cited as common to 40 m in the Archipelago Los Roques (Cervigón, 1966). Nassau groupers tagged with depth sensors in Belize exhibited marked changes in depth at specific times throughout the year: 15–34 m from May through December, followed by movement to very deep areas averaging 72 m with a maximum of 255 m for a few months during spawning periods, then returning to depths of about 20 m in April (Starr et al., 2007).

Adults lead solitary lives outside of spawning periods and tend to be secretive, often seeking shelter in reef crevices, ledges, and caves; rarely venturing far from cover (Bardach, 1958; Starck and Davis, 1966; Bohlke and Chaplin, 1968; Smith, 1961, 1971; Carter, 1988, 1989). Although they tend to be solitary, individuals will crowd peacefully in caves or fish traps with some proclivity to re-enter fish traps resulting in multiple recaptures (Randall, 1962; Sadovy and Eklund, 1999; Bolden, 2001). Nassau grouper have the ability to home (Bardach et al., 1958; Bolden, 2000) and remain within a highly circumscribed area for extended periods (Randall, 1962 1963; Carter et al., 1994; Bolden, 2001). In the Florida Keys, adult Nassau grouper (n=12) were found more often in high- and moderate-relief habitats compared to low-relief reefs (Sluka et al., 1998). Habitat complexity has been found to influence home range size of adult Nassau grouper, with larger home ranges at less structurally-complex reefs (Bolden, 2001). Nassau grouper are Start Printed Page 130 diurnal or crepuscular in their movements (Collette and Talbot, 1972). Bolden (2001) investigated diel activity patterns via continuous acoustic telemetry and found Nassau groupers are more active diurnally and less active nocturnally, with activity peaks at 1000 and 2000 hours.

Importance of Shelter

For many reef fishes, access to multiple, high-quality habitats and microhabitats represents a critical factor determining settlement rates, post-settlement abundances, mortality rates, and growth rates, because suitably sized refuges provide protection from predators and access to appropriate food (Shulman, 1984; Hixon and Beets, 1989; Eggleston et al., 1997, 1998; Grover et al., 1998; Lindeman et al., 2000; Dahlgren and Eggleston, 2000, 2001; Dahlgren and Marr, 2004; Eggleston et al., 2004). Many reef fish and invertebrates use hardbottom areas located between the nearshore environment and the outer reefs as juveniles.

As Nassau grouper move from their nearshore settlement habitat, through hardbottom and seagrass mosaic habitats, to the offshore reefs they occupy as adults, shelter provides an essential life history function by reducing risk of predation and promoting successful ambush hunting. Availability of suitably sized shelters may be a key factor limiting successful settlement and survival for juvenile Nassau grouper and related species that settle and recruit to shallow, off-reef habitats (Hixon and Beets, 1989; Eggleston, 1995; Lindeman et al., 2000; Dahlgren and Eggleston, 2001). In addition, shelters of different sizes may govern the timing and success of ontogenetic movements to adult habitats (Caddy, 1986; Moran and Reaka, 1988; Eggleston, 1995). Camp et al. (2013) found juvenile Nassau grouper use shelters of varying sizes and degrees of complexity. Suitably-sized refuge from predators is expected to be a key characteristic supporting the survival and growth of juvenile Nassau grouper and other species, with access to food resources likely representing another key, and sometimes opposing, characteristic (Shulman, 1984; Hixon and Beets, 1989; Eggleston et al., 1997, 1998; Grover et al., 1998; Dahlgren and Eggleston, 2001). The transition to these new habitats, however, heightens predation risk if habitats are far apart (Sogard, 1997; Tupper and Boutilier, 1997; Almany and Webster, 2006) and there is minimal cover between them (Dahlgren and Eggleston, 2000; Caddy, 2008). Nassau grouper rely on shelter to safely move between these interconnected habitats. Benthic juvenile fish rely on complex structure to protect themselves from predation and the simplification of habitats can lead to declines in recruitment (Caddy, 2008). Stock replenishment is threatened by degradation of the habitats of successive life stages. Nassau grouper must often risk predation by crossing seascapes where cover connectivity is limited. Loss of cover therefore increases mortality, reduces foraging success, and affects other life-history activities.

Diet

In the planktonic stage, the yolk and oil in the egg sac nourish the early yolk-sac larva as it develops prior to hatching. The pelagic larvae begin feeding on zooplankton approximately 2–4 days after hatching when a small mouth develops (Tucker and Woodward, 1994). In the laboratory, grouper larvae eat small rotifers, copepods, and other zooplankton, including brine shrimp (Tucker and Woodward, 1994). Diet information for newly settled Nassau grouper is based on visual observations indicating that young fish (20.2–27.2 mm SL) feed on a variety of plankton, including pteropods, ostracods, amphipods, and copepods (Greenwood, 1991; Grover et al., 1998). Similarly, in the Bahamas, recently settled and post-settlement stage (25–35 mm TL) Nassau grouper living within the macroalgae and seagrass blades have a primarily invertebrate diet of xanthid crabs, hippolytid shrimp, bivalves, and gastropods (Eggleston, 1995).

More detailed diet information is available for juveniles and adults. Stomach contents of juvenile Nassau grouper (5–19 cm TL) collected from seagrass beds near Panama contained primarily porcellanid and xanthid crabs with minor amounts of fish (Heck and Weinstein, 1989). Four dominant prey were ingested by small (< 20 cm TL) Nassau grouper in the Bahamas: stomatopods, palaemonid shrimp, and spider and portunid crabs (Eggleston et al., 1998). Fish and spider crabs made up the bulk of the diet for both mid-size (20.0–29.9 cm TL) and large (>30 cm TL) Nassau grouper in opposite proportion: spider crabs dominated the diet of the mid-size fish, while fish were the most important prey for large Nassau grouper (Eggleston et al., 1998). Juveniles generally engulfed their prey whole (Eggleston et al. 1998). Smaller juveniles ate greater numbers of prey than larger grouper, but the individual prey items ingested by larger grouper weighed more (Eggleston et al., 1998). Similar ontogenetic changes in the Nassau grouper diet were reported by Randall (1965) and Eggleston et al. (1998) who analyzed stomach contents and determined that juveniles fed mostly on crustaceans, while adults foraged mainly on fishes.

As adults, Nassau grouper are unspecialized-ambush-suction predators (Randall, 1965; Thompson and Munro, 1978) that lie under shelter, wait for prey, and then quickly expand their gill covers to create a current to engulf prey by suction (Thompson and Munro, 1978; Carter, 1986) and swallow their prey whole (Werner, 1974, 1977). Numerous studies describe adult Nassau groupers as piscivores, with their diet dominated by reef fishes: parrotfish (Scaridae), wrasses (Labridae), damselfishes (Pomacentridae), squirrelfishes (Holocentridae), snappers (Lutjanidae), groupers (Epinephelidae) and grunts (Haemulidae) (Randall and Brock, 1960; Randall, 1965, 1967; Parrish, 1987; Carter et al, 1994; Eggleston et al., 1998). The propensity for adult Nassau grouper to consume primarily fish (Randall, 1965; Eggleston et al., 1998) may be due to increased visual perception and swimming-burst speed with increasing body size ( e.g., Kao et al., 1985; Ryer, 1988). Large Nassau grouper are probably foraging on reef-fish prey that are either associated with a reef (Eggleston et al., 1997) or adjacent seagrass meadows. In general, groupers have been characterized from gut content studies as generalist opportunistic carnivores that forage throughout the day (Randall, 1965, 1967; Goldman and Talbot, 1976; Parrish, 1987), and perhaps being more active near dawn and dusk (Parrish, 1987; Carter et al., 1994). Comparison of Nassau grouper stomach contents from natural and artificial reefs were found to be generally similar (Eggleston et al., 1999). While Smith and Tyler (1972) classified Nassau grouper as nocturnally active residents, Randall (1967) investigated Nassau grouper gut contents and determined that although feeding can take place around the clock, most fresh food is found in stomachs collected in the early morning and at dusk. Silva Lee (1974) reported Nassau grouper with empty stomachs throughout daylight hours.

Spawning

The most recognized Nassau grouper habitats are the sites where adult males and females assemble briefly at predictable times during winter full moons for the sole purpose of reproduction. These spawning aggregation sites are occupied by Nassau grouper during winter full moon Start Printed Page 131 periods, from about November and extending to May (USVI) (Nemeth et al., 2006). Aggregations consist of hundreds, thousands, or, historically, tens of thousands of individuals. Some aggregations have consistently formed at the same locations for 90 years or more (see references in Hill and Sadovy de Mitcheson 2013). All known reproductive activity for Nassau grouper occurs in aggregations; pair spawning has not been observed. About 50 spawning aggregation sites have been recorded, mostly from insular areas in the Bahamas, Belize, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Turks and Caicos, and the USVI; however, Nassau grouper may no longer form spawning aggregations at many of these sites (Figure 10 in Hill and Sadovy de Mitcheson, 2013). While both the size and number of spawning aggregations has diminished, spawning is still occurring in some locations (NMFS, 2013).

Spawning aggregation sites typically occur near the edge of insular platforms in a wide (6–50 m) depth range, as close as 350 m to the shore, and close to a drop-off into deep water. These sites are characteristically small, highly circumscribed areas, measuring several hundred meters in diameter, with a diversity of bottom types, including soft corals, sponges, stony coral outcrops, and sandy depressions (Craig, 1966; Smith 1990; Beets and Friedlander, 1992; Colin, 1992; Aguilar-Perera, 1994). Adults are known to travel hundreds of kilometers (Bolden, 2000) to gather at specific spawning aggregation sites. While aggregated, the Nassau grouper are extremely vulnerable to overfishing (Sadovy de Mitcheson et al., 2008).

It is not known how Nassau grouper select and locate aggregation sites or why they aggregate to spawn. Variables that are considered to influence spawning site suitability include geomorphological characteristics of the seabed, hydrodynamics including current speed and prevailing direction of flow to disperse eggs and larvae, seawater temperature, and proximity to suitable benthic habitats for settlement (Kobara and Heyman, 2008). The link between spawning sites and settlement sites is not well understood. The geomorphology of spawning sites has led researchers to assume that offshore transport was a desirable property of selected sites. However, currents in the vicinity of aggregation sites do not necessarily favor offshore egg transport, leaving open the possibility that some stocks are at least partially self-recruiting. Additional research is needed to understand these spatial dynamics.

The biological cues known to be associated with Nassau grouper spawning include photoperiod ( i.e., length of day), water temperature, and lunar phase (Colin, 1992). The timing and synchronization of spawning may be to accommodate immigration of widely dispersed adults, facilitate egg dispersal, or reduce predation on adults or eggs.

Movement

“Spawning runs,” or movements of adult Nassau grouper from coral reefs to spawning aggregation sites, were first described in Cuba in 1884 by Vilaro Diaz, and later by Guitart-Manday and Juarez-Fernandez (1966). Nassau grouper migrate to aggregation sites in groups numbering between 25 and 500, moving parallel to the coast or along shelf edges or inshore reefs (Colin, 1992; Carter et al., 1994; Aguilar-Perera and Aguilar-Davila, 1996; Nemeth et al., 2009). Distance traveled by Nassau grouper to aggregation sites is highly variable; some fish move only a few kilometers, while others move up to several hundred kilometers (Colin, 1992; Carter et al., 1994; Bolden, 2000). Observations suggest that individuals may return to their original home reef following spawning (Semmens et al., 2007).

Larger fish are more likely to return to aggregation sites and spawn in successive months than smaller fish (Semmens et al., 2007). Nassau grouper have been shown to have high site fidelity to an aggregation site, with 80 percent of tagged Nassau grouper returning to the same aggregation site, Bajo de Sico, each year over the 2014–2016 tracking period in Puerto Rico (Tuohy et al., 2016). The area occupied during spawning by Nassau grouper is smaller at Bajo de Sico compared to Grammanik Bank off St. Thomas. Acoustic detections of tagged Nassau grouper revealed a southwesterly movement from the Puerto Rican shelf to the Bajo de Sico in a narrow corridor (Tuohy et al., 2017).

Spawning Activity and Behavior

Spawning occurs for up to 1.5 hours around sunset for several days (Whaylen et al., 2007). All spawning events have been recorded within 20 minutes of sunset, with most within 10 minutes of sunset (Colin, 1992). At spawning aggregation sites, Nassau grouper tend to mill around for a day or two in a “staging area” adjacent to the core area where spawning activity later occurs (Colin, 1992; Kadison et al., 2010; Nemeth, 2012). Courtship is indicated by two behaviors that occur late in the afternoon: “following” and “circling” (Colin, 1992). The aggregation then moves into deeper water shortly before spawning (Colin, 1992; Tucker et al., 1993; Carter et al., 1994). Progression from courtship to spawning may depend on aggregation size, but generally fish move up in the water column, with an increasing number of the fish exhibiting the bicolor phase ( i.e. when spawning animals change to solid dark and white colors, temporarily losing their characteristic stripes) (Colin, 1992; Carter et al., 1994). Following the release of sperm and eggs, there is a rapid return of the spawning individuals to the bottom.

Repeated spawning occurs at the same site for up to three consecutive months generally around the full moon or between the full and new moons (Smith, 1971; Colin, 1992; Tucker et al., 1993; Aguilar-Perera, 1994; Carter et al., 1994; Tucker and Woodward, 1994). Examination of female reproductive tissue suggests multiple spawning events across several days at a single aggregation (Smith, 1972). A video recording shows a single female in repeated spawning rushes during a single night, repeatedly releasing eggs (Colin, 1992).

Spawning Aggregations in U.S. Waters

The best available information suggests that spawning in U.S. waters occurs at three sites: Bajo de Sico in waters off the coast of Puerto Rico (Scharer et al., 2012), Grammanik Bank in waters off the coast of the USVI (Nemeth et al., 2006), and Riley's Hump within the Tortugas South Ecological Reserve in Florida (Locascio and Burton 2015; J. McCawley, Pers. comm., December 9, 2022). These three sites are all at least partially protected under existing fishery regulations, as discussed below. For all three sites, it is unclear whether they are reconstituted ( i.e., reestablished after depletion) or novel spawning sites. Nassau grouper spawning has been positively confirmed at Bajo de Sico (Scharer et al. 2012; Scharer et al. 2017; Tuohy et al. 2017) and Grammanik Bank (Nemeth et al. 2006; Nemeth et al. 2009; Nemeth et al. 2023). At Riley's Hump, visual and acoustic evidence suggests that spawning is occurring there (Locascio and Burton 2015; J. McCawley, Pers. comm., December 9, 2022). A spawning aggregation site historically existed on the eastern tip of Lang Bank, USVI that was extirpated in the early 1980s; however, we have insufficient information regarding its continued existence or its current value to Nassau grouper spawning. Start Printed Page 132

Bajo de Sico

Bajo de Sico, in waters off the coast of Puerto Rico, is a submerged offshore seamount located in the Mona Passage off the insular platform of western Puerto Rico approximately 29 km west of Mayaguez (Scharer-Umpierre et al., 2014). Reef bathymetry is characterized by a ridge of highly rugose rock promontories ranging in depths from 25 to 45 m, which rise from a mostly flat, gradually sloping shelf that extends to 100 m deep. Below this depth, the shelf ends in a vertical wall that reaches depths of 200–300 m to the southeast and over 1,000 m to the north (Tuohy et al., 2015). Most of the shallow (<180 m depth) areas of this 11 km2 seamount are located in the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Bajo de Sico is considered a mesophotic coral ecosystem due to the range of depths and coral/algae development. Where water depths are less than 50 m, this area is characterized by a reef top, vertical reef wall and rock promontories, colonized hardbottom with sand channels, uncolonized gravel, and substantial areas of rhodolith reef habitat (Garcia-Sais et al., 2007).

In 1996, NMFS approved a 3-month seasonal fishing closure (December 1 through February 28) in Federal waters at Bajo de Sico to protect spawning aggregations of red hind (61 FR 64485, December 5, 1996); the closure also partially protects Nassau grouper spawning aggregations (Scharer et al., 2012). During the closure period, all fishing was prohibited (61 FR 64485). A later rule prohibited the use of bottom-tending gear, including traps, pots, gillnets, trammel nets, and bottom longlines, in Bajo de Sico year-round (70 FR 62073, October 28, 2005). In 2010, NMFS approved a modification to the Bajo de Sico seasonal closure, extending the closure period to 6-months (October 1 through March 31), altering the restriction to prohibit fishing for and possessing Caribbean reef fish in or from Federal waters at Bajo de Sico during the closure period, and prohibiting anchoring by fishing vessels year-round in the area (75 FR 67247, November 2, 2010). The 2010 rule is still in place.

In February 2012, a Nassau grouper spawning aggregation was identified at Bajo de Sico when at least 60 individuals were observed via video and audio recordings exhibiting reproductive behaviors (Scharer et al., 2012). While actual spawning was not observed on the 2012 video recordings, all four Nassau grouper spawning coloration patterns and phases (Smith, 1972; Colin, 1992; Archer et al., 2012) were observed, including the bi-color phase associated with peak spawning activity (Scharer et al., 2012). Subsequent diver surveys conducted from January 25 to April 5, 2016, indicated between 5–107 individuals at the site, with the greatest number occurring in February (Scharer et al., 2017). The highest detection rate of tagged Nassau grouper (n=29) occurred in February and March, with other detections in January and April, all peaking following the full moon (Scharer et al., 2017). The depth range (40 to 155 m) being used by Nassau grouper at the Bajo de Sico exceeds other locations (Scharer et al., 2017).

Grammanik Bank, USVI

Grammanik Bank, USVI is located approximately 4 km east of the Hind Bank Marine Conservation District (MCD), on the southern edge of the Puerto Rican Shelf. Grammanik Bank is a narrow deep coral reef bank (35–40 m) about 1.69 km long and 100 m wide at the widest point located on the shelf edge about 14 miles south of St. Thomas. It is bordered to the north by extensive mesophotic reef and to the south by a steep drop-off and a deep Agaricea reef at 200–220 ft (60–70 m) (Nemeth et al., 2006; Scharer et al., 2012). The benthic habitat is primarily composed of a mesophotic reef at depths between 30–60 m, which includes a combination of Montastrea and Orbicella coral and hardbottom interspersed with gorgonians and sponges (Smith et al., 2008). Corals are present on Grammanik Bank at depths between 35 and 40 m and the coral bank is bordered to the east and west by shallower (25 to 30 m) hardbottom ridges along the shelf edge, which is sparsely colonized by corals, gorgonians, and sponges (Nemeth et al., 2006). When Hind Bank MCD was established in 1999 as the first no-take fishery reserve in the USVI to protect coral reef resources, reef fish stocks, including red hind ( E. guttatus), and their habitats (64 FR 60132, November 4, 1999), fishing pressure is thought to have moved to the adjacent Grammanik Bank (Nemeth et al., 2006). Fishing is prohibited for all species at Hind Bank MCD year-round. At Grammanik Bank, all fishing for species other than highly migratory species is prohibited from February 1 to April 30 of each year. The initial intent of the spatial closure was to protect yellowfin grouper ( Mycteroperca venenosa) when they aggregate to spawn (70 FR 62073, October 28, 2005; Scharer et al., 2012), but this closure has also proven beneficial for the protection of spawning aggregations of tiger grouper ( M. venenosa), yellowmouth grouper ( M. interstitialis), cubera snapper ( Lutjanus cyanopterus) and Nassau grouper (Nemeth et al. 2006).

Approximately 100 Nassau grouper were observed aggregating at the Grammanik Bank in 2004 between January and March (Nemeth et al., 2006). This discovery marked the first documented appearance of a Nassau grouper spawning aggregation site within U.S. waters since the mid-1970s (Kadison et al., 2009); however, commercial fishers were quick to target this new aggregation site and began to harvest both yellowfin ( Mycteroperca venenosa) and Nassau groupers (Nemeth et al., 2006). In 2005, NMFS approved a measure developed by the Caribbean Fisheries Management Council (70 FR 62073, October 10, 2005) that closed the Grammanik Bank to fishing for all species, with an exception for highly migratory species, from February 1 through April 30 each year. Diver surveys and collection of fish in traps recorded 668 Nassau grouper at Grammanik Bank between 2004 and 2009 (Kadison et al., 2010). The fish were of reproductive size and condition and arrived on and around the full moon in February, March, and April and then departed 10 to 12 days after the full moon. The number of Nassau grouper observed in diver visual surveys suggests that Nassau grouper spawning biomass has increased at the aggregation site from a maximum abundance of 30 individuals sighted per day in 2005, to 100 per day in 2009 (Kadison et al., 2009). By 2013, a maximum abundance of 214 individuals was recorded per day (Scharer-Umpierre et al., 2014). Since then the maximum number of Nassau grouper counted per day during spawning periods has continued to increase, reaching over 500 in 2020, 750 in February 2021, and at least 800 in January 2022 (R. S. Nemeth, unpublished data).

The behavior of Nassau grouper in the aggregation has also changed dramatically in the past few years. From 2004 to 2019, Nassau grouper were found aggregating in small groups of 10, 20, or maybe as high as 40 individuals, resting close to the bottom among the coral heads. Nassau grouper were also observed to swim down the slope to 60 to 80 m, presumably to spawn, to an extensive Agaricia larmarki reef that Nassau grouper also use for shelter (R. S. Nemeth, unpublished data). These deep movements were later verified with acoustic telemetry data, and Nassau grouper were suspected of spawning near this deep reef area. Since 2020, Nassau grouper have been observed in groups of 100 to 300 fish Start Printed Page 133 aggregated 5 to 10 m above the bottom. On January 24, 2022 (7 days after full moon), researchers captured the first ever observation of Nassau grouper spawning at the Grammanik Bank at 17:40 and a second spawning rush at 18:10 (R.S. Nemeth, pers. comm., February 13, 2022). Spawning occurred well above the bottom in 30 to 40 m depth. Vocalization by Nassau grouper has suggested that abundance and spawning of Nassau grouper peaked at Grammanik Bank after the full moons in January through May (Rowell et al., 2013).

Nemeth et al. (2009) first reported synchronous movement of Nassau grouper during the spawning period between Hind Bank MCD and Grammanik Bank using acoustic telemetry. Both Nassau and yellowfin groupers primarily used two of three deep (50 m) parallel linear reefs that link Grammanik Bank with the Hind Bank MCD and lie in an east-west orientation parallel to the shelf edge. The linear reef about 300 to 500 m north of the shelf edge was used mostly by Nassau grouper. Acoustic telemetry and bioacoustic recordings were later integrated by Rowell et al. (2015) to identify a synchronized pathway taken by pre- and post -spawning Nassau grouper to the Grammanik Bank spawning site from the nearby Hind Bank MCD. While not every Nassau grouper was found to use this spawning route, the majority (64 percent) of the tagged fish followed this specific route on a regular or often daily basis during the week when spawning was occurring at Grammanik Bank. Because 56 percent of the tagged Nassau grouper (n=10) traversed between Hind Bank MCD and Grammanik Bank during spawning, it was suggested by Nemeth et al. (2009) and by Nemeth et al. (2023), that the boundary of the Grammanik Bank fishing closure area be expanded to the south, north, and west to protect the moving fish.

It remains unknown whether the increasing abundance at the Nassau grouper aggregation at Grammanik Bank is a result of: (1) Remnant adults from the nearby overfished aggregation site (the historical Grouper Bank, now located within the Hind Bank Marine Conservation District) shifting spawning locations to the Grammanik Bank, a distance of about 5 km; (2) Larvae dispersed from distant spawning aggregations elsewhere in the Eastern Caribbean that have settled on the St. Thomas/St. John shelf, matured, and migrated to the Grammanik Bank spawning site; or (3) Self-recruitment by local reproduction from the remnant population. Each of these recovery scenarios is supported by various researchers who have observed these same phenomena in separate locations. The first scenario is supported by Heppel et al. (2013), who found that Nassau grouper visit multiple aggregation sites during the spawning season, yet all fish aggregate and spawn at a single location. The second scenario is supported by Jackson et al. (2014), who found strong genetic mixing of Nassau grouper populations among the Lesser and Greater Antilles, including Turks and Caicos. Bernard et al. (2015) also found that external recruitment is an important driver of the Grammanik Bank spawning aggregation recovery. The third scenario relies on self-recruitment, a popular strategy of recruitment among marine species.

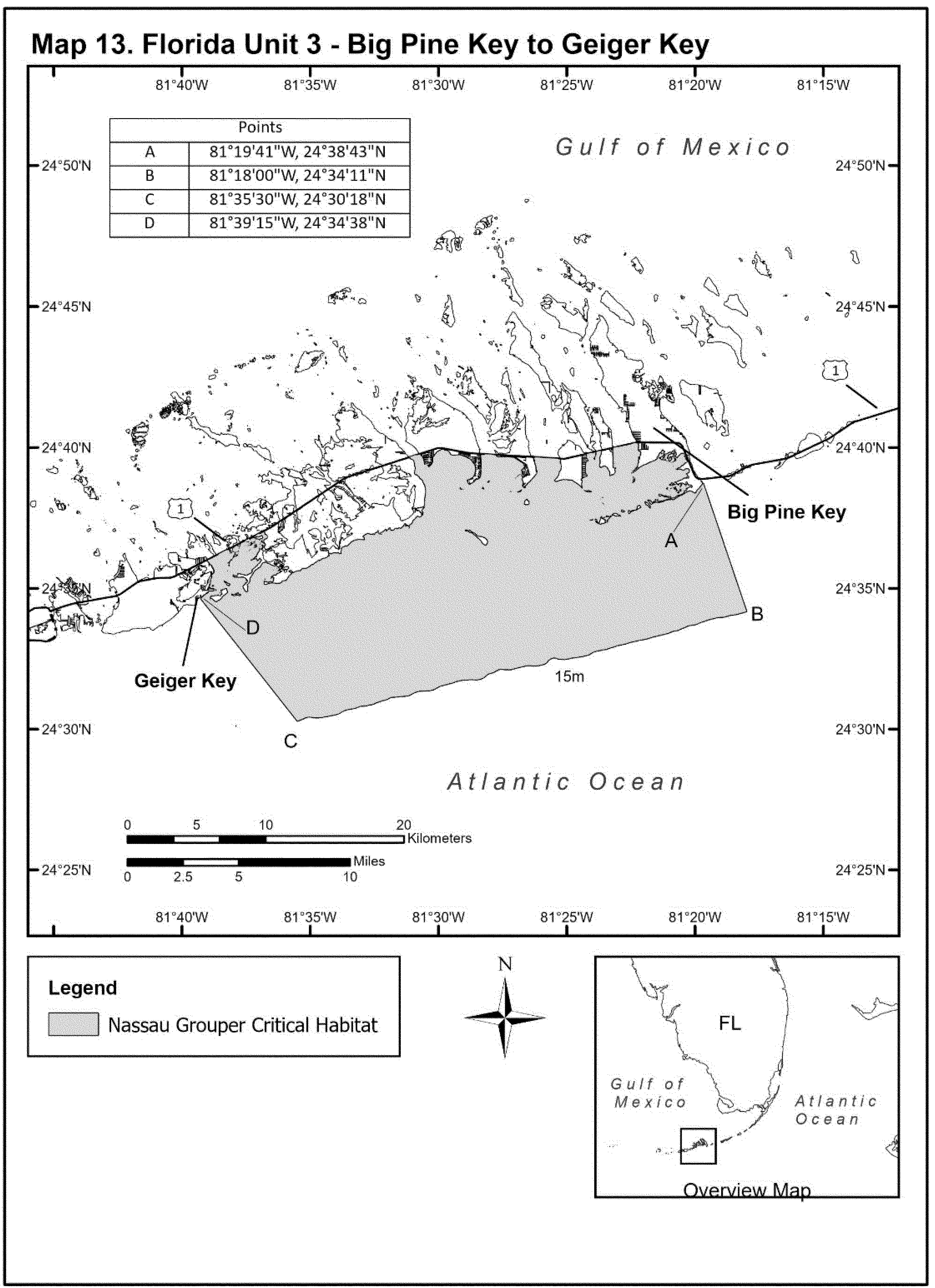

Riley's Hump, Florida

Riley's Hump, Florida, is located approximately 16 km to the southwest of the Dry Tortugas National Park and is within the boundaries of the Tortugas South Ecological Reserve. The larger area of the Dry Tortugas—which encompasses the Dry Tortugas National Park, the Tortugas Bank, the Tortugas South Ecological Reserve, and the Tortugas North Ecological Reserve—includes a series of carbonate banks and sand shoals located southwest of the Florida continental margin. Riley's Hump is one of these carbonate banks, separated from the Tortugas Bank to the north by a deep trough, which is filled with thick sedimentary deposits. The bank crests at about 30 m, and has a 20 m escarpment at the shelf break on the south side of the bank (Mallinson et al., 2003). While coral cover on Riley's Hump is relatively low, fish diversity is high and is characterized by species that are rare in other locations (Dahlgreen et al., 2001).

Riley's Hump is located within the boundaries of the Tortugas South Ecological Reserve, which has been closed to fishing since 2001, when both the North and South Ecological Reserves were established, adjacent to the Dry Tortugas National Park. The Tortugas South Ecological Reserve hosts several known annual spawning aggregations, including aggregations of mutton snapper, and likely black grouper, red grouper, red hind, and Nassau grouper (Locascio and Burton, 2015). The location and depth of Riley's Hump make it particularly difficult to conduct annual monitoring projects. However, visual surveys have documented higher densities of Nassau groupers at Riley's Hump than anywhere in Florida, and are estimated at roughly 1 adult per 0.04 acres (D. Morley, Pers. comm., September 6, 2023). Some observations have included individuals displaying colorations and producing sounds associated with spawning (Locascio and Burton, 2015, J. Locascio, Pers. comm., September 6, 2023).

The mechanism behind the spawning aggregation at Riley's Hump remains unclear. The southern Florida reef tract is near the northern extent of the range of Nassau grouper, and the species is extremely rare in this location. However, historical accounts suggest that the species was once more common in the area; this aggregation could be a remnant of a depleted historical aggregation, or a new aggregation that is being formed by individuals which have settled and matured in the area.

Summary of Changes From the Proposed Critical Habitat Designation

We evaluated the comments and new information received from the public during the public comment period. Based on our consideration of these comments and the best scientific information available (as noted below in the Summary of Comments and Responses section), we made the following substantive changes to the final rule:

1. Based on new information received during the public comment period, coupled with additional local ecological knowledge and baseline ecological studies we obtained following publication of the proposed rule, and as described above (see Natural History and Habitat Use), Riley's Hump, Florida, is considered a third spawning aggregation area in U.S. waters, and we are including this area in the critical habitat designation. To reflect this change in the critical habitat designation, we added the following textual description of the Riley's Hump spawning unit to read as follows: Spawning Site Unit 3—Riley's Hump—All waters encompassing Riley's Hump located southwest of the Dry Tortugas out to the 35 m isobath on the north, west, and east side of the hump and out to the 50 m isobath on the south side of the hump. See comment 10 and our response to the comment for further explanation of this change.

2. We extended the offshore boundary of Puerto Rico Unit 1 out to the 50 m isobaths off the islands of Mona and Monito and modified the associated description to read as follows: Puerto Rico Unit 1—Isla de Mona and Monito—All waters surrounding the islands of Mona and Monito from the shoreline to the 50 m isobaths. This change was driven by years of monitoring data and scientific observations we received during the public comment period from an Start Printed Page 134 internationally-recognized researcher, whose work includes in-depth studies of habitat use by Nassau grouper at these locations. Comment 8 and our response to the comment provides further explanation of this change.

3. We extended the offshore boundary for Puerto Rico Unit 2 out to the 50 m isobaths off the island of Desecheo and revised the associated textual description to read as follows: Puerto Rico Unit 2—Desecheo Island—All waters surrounding the island of Desecheo from the shoreline to the 50 m isobath. This change was driven by years of monitoring data and scientific observations we received from the same researcher regarding this specific habitat unit. See comment 8 and our response to the comment for a more detailed explanation of this change.

We updated the maps of Puerto Rico Units 1 and 2 to reflect the extension of these units' boundaries and have included a new map of Spawning Site Unit 3—Riley's Hump. As a result of these changes, the total area encompassed by this final designation has increased by 32.4 sq. km (12.51 sq. miles), compared to the proposed designation.

Other Changes

In addition to substantive changes in the final rule described above, we also made clarifying changes to the final rule, and to the Critical Habitat Report, in response to public comments and new information. Specifically, the economic values are updated and detailed in both the final rule and the Critical Habitat Report. We considered whether the extended boundaries for Puerto Rico Units 1 and 2 and the addition of Spawning Site Unit 3—Riley's Hump would alter the number and nature of ESA section 7 consultations included in the analysis and whether any additional economic, national security, other relevant impacts that were not previously considered could be identified. We confirmed that no additional section 7 consultations relevant to the expansion of Puerto Rico Units 1 and 2 or the addition of Spawning Site Unit 3—Riley's Hump are expected or should be incorporated into the economic analysis, and we received no additional information regarding future planned or expected federal activities within these areas. Therefore, we project no additional economic impacts as a result of these changes. Further, the added areas are already located within reserve areas and are not used for military purposes. For this reason, the newly added areas pose no impacts to national security. No other relevant impacts were identified as a result of these changes in the specific areas of the critical habitat. Therefore, while the specific areas under consideration changed slightly to include an additional 32.4 sq. km (12.51 sq. miles), no changes were made to the conclusions of our ESA section 4(b)(2) analysis.

Summary of Public Comments and Responses

We solicited comments on the proposed rule and the supporting Critical Habitat Report during a 60-day comment period (87 FR 62930, October 17, 2022). To facilitate public participation, the proposed rule was made available on our website and comments were accepted via both standard mail and through the Federal eRulemaking portal, https://www.regulations.gov.

We received 18 comments; of these, 16 comments were generally supportive of the proposed rule. One comment opposed the proposed designation, but it provided no rationale or additional information to controvert our analysis or conclusions. Another comment was not relevant to the subject of Nassau grouper critical habitat and was likely submitted to the wrong comment docket. All public comments are posted on the Federal eRulemaking Portal (docket number: NOAA–NMFS–2022–0073). We reviewed and fully considered all relevant public comments and significant new information received in developing the final critical habitat designation. Where appropriate, we have combined similar comments from multiple commenters and addressed them together.

General Comments in Support of the Proposed Rule

Comment 1: The majority (89 percent) of the comments we received were supportive of the proposed rule and did not include substantive content or suggest any changes to the proposed critical habitat designations. Many of these comments noted that critical habitat designation is a crucial aspect of population recovery while also noting benefits to the surrounding ecosystem. Other comments pointed to the decline in habitat quality throughout the range of the Nassau grouper and the consequent need to preserve and protect habitat that is deemed critical to the species. Many of the comments also acknowledged human-induced reduction of the species via overfishing, specifically at spawning aggregation sites.

Response: We appreciate these comments. We look forward to working with stakeholders throughout the range of the Nassau grouper to promote the recovery of the species, and acknowledge that the critical habitat designation is one step in that process. As described in the final listing determination (81 FR42268), we concur that overfishing, particularly at spawning aggregations, is the primary threat to the species.

Comments on Need for Special Management Considerations or Protection

Comment 2: One commenter requested that we expand the Need for special management considerations or protection section.

Response: The commenter did not provide any additional detail as to what aspect of the section needed further expansion or explain why the commenter thought our analysis was insufficient. In response to this comment, we reviewed our discussion and explanation of how the identified physical and biological features essential to the conservation of Nassau grouper meet the “may require special management considerations or protections” aspect of the statutory definition of “critical habitat.” As described in the proposed rule (87 FR 62930), we found that the essential feature components that support settlement, development, refuge, and foraging (essential feature 1, components a through d) are particularly susceptible to impacts from human activity because of the relatively shallow water depth range where these features occur as well as their proximity to the coast. As a result, these features may be directly and indirectly impacted by activities such as coastal and in-water construction, dredging and disposal activities, beach nourishment, stormwater run-off, wastewater and sewage outflow discharges, point and non-point source pollutant discharges, fishing activities, and anthropogenically-induced climate change. The spawning aggregation sites essential feature (essential feature 2) is affected by activities that may make the sites unsuitable for reproductive activity, such as activities that inhibit fish movement to and from the sites or within the sites during the period the fish are expected to spawn, or create conditions that deter the fish from selecting the site for reproduction. Further, because the spawning aggregation sites are so discrete and rare and the species' reproduction depends on their use of aggregation sites, the species is highly vulnerable at these locations and loss of an aggregation site could lead to significant population impacts. By identifying and discussing Start Printed Page 135 these various sources and types of impacts on the essential features of the critical habitat we provide sufficient demonstration that the essential features meet the “may require special management or protections” prong of the definition of critical habitat. We note that we are not obligated to identify all possible management concerns or protections that may be relevant, nor does the ESA require that we do so. However, in response to this comment, we note that activities that inhibit fish movement to and from spawning sites or create conditions that deter the fish from selecting the site for reproduction by altering the essential features described in this rule, might include the placement of in-water barriers, direct physical destruction of benthic habitats both at the site and within migratory corridors, and pollution ( e.g., chemical or noise) that renders the site less biologically suitable.

Comments on Economic Analysis

Comment 3: One commenter asked whether private landowners were contacted regarding the economic impact of the proposed critical habitat designation.

Response: Private landowners as well as all other stakeholders were given an opportunity to provide comments during the 60-day public comment period on the proposed rule. In addition, a thorough economic analysis was conducted as an integral part of the critical habitat proposed rule (81 FR 42268, October 17, 2022). All publicly available resources were used to identify economic impacts that would result from the designation of critical habitat. As explained in the economic analysis, the only types of activities for which private landowners might incur costs stemming from the critical habitat are those related to in-water and coastal construction ( e.g., docks, boat ramps, marina). Further, the economic analysis concludes that the designation would not result in the need for changes to such projects beyond those already required due to existing (“baseline”) regulations, such as the presence of the ESA-listed Nassau grouper and corals and existing designated critical habitat for seven species of listed corals. The only incremental costs potentially incurred by private landowners are the administrative costs of addressing effects to Nassau grouper critical habitat through informal and formal section 7 consultations, and most of these costs would be borne by the responsible federal action agency ( e.g., U.S. Army Corps of Engineers). Due to the presence of ESA-listed species and designated critical habitat for other species, these section 7 consultations would occur absent the designation of critical habitat for Nassau grouper. The analysis projects that fewer than two section 7 formal consultations and fewer than 80 informal consultations on construction-related projects would consider effects to Nassau grouper critical habitat over the next 10 years. This equates to less than 0.2 formal consultations and fewer than eight informal consultations per year. Based on the best available information, third party administrative section 7 costs directly attributable to Nassau grouper critical habitat would be approximately $510 per informal consultation (2022 dollars). It is highly unlikely that these costs would deter a private landowner from completing a construction project. As there would be no incremental costs to or restrictions placed on private landowners conducting activities that do not involve a federal agency, there is no basis for concluding there would be any loss in property values or impact on the scope or volume of non-federally regulated activities.

Comments on Exclusion of Managed Areas

Comment 4: One commenter asked why managed areas, as defined in the proposed rule, are not considered for critical habitat designation. A separate commenter referred to the proposed treatment of navigation channels as managed areas and requested that NMFS include navigation channels and their immediate surroundings within the critical habitat designation. This commenter also stated that federal activities that adversely affect critical habitat should be mitigated under ESA section 7 and not excluded from critical habitat designation.

Response: The proposed rule specified that an area would not be included in critical habitat if it is a managed area where the substrate is continually disturbed by planned management activities authorized by local, state, or Federal governmental entities at the time of critical habitat designation and will continue to be disturbed by such management. Examples of managed areas included dredged navigation channels, shipping basins, vessel berths, and active anchorages. Due to the ongoing use and maintenance of these managed areas and the persistent disturbance of the bottom, the areas are poor habitat with little to no ability to support the long-term conservation of Nassau grouper. Therefore, we did not include managed areas within the proposed critical habitat designation. We also explained in the proposed rule that channel dredging may result in sedimentation impacts beyond the actual channel edge, and to the extent these impacts are persistent, they are expected to recur whenever the channel is dredged and are of such a level that the areas in question are currently unsuitable to support the essential features of critical habitat. As a result, we consider such areas as part of the managed areas that are not included in the final designation. We note that ESA section 7 consultations on actions that propose new or modified navigation channels will consider impacts to the essential features of Nassau grouper critical habitat outside of pre-existing managed areas.

Comments on Predation Threats to the Species

Comment 5: One commenter questioned why impacts from invasive lionfish were not included in the critical habitat proposed rule and provided a reference that observed Nassau grouper in direct competition with the red lionfish in high quality habitats, as well as predation by lionfish on juvenile Nassau grouper.

Response: The final listing determination for Nassau grouper (81 FR42268; June 29, 2016) considered the factors for listing as outlined in section 4(a)(1). One of these factors (factor C) identifies predation as a potential basis for listing a species. Based on the extinction risk analysis and supporting documentation in the biological report, it was determined that Nassau grouper is at a “very low risk” of extinction due to predation. Any additional threats from invasive species could be considered under risk factor E ( i.e., other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence), however, competition with invasive lionfish was not considered as a threat to the existence of the species, nor were any other invasive species considered as direct threats to the existence of Nassau grouper. Nassau grouper occupy a niche as a large-bodied predator within coral reef fish communities throughout its range. As an integral part of the fish community, they are subjected to competition with a variety of other species, including the red lionfish ( Pterois volitans), but we have no information to undermine our previous conclusion that Nassau grouper is at low risk of extinction due to predation. Additionally, there is no indication that red lionfish alter the essential features of the critical habitat designation. We reviewed and considered the comment, as well as the referenced paper, and did not find a basis to alter the areas designated as critical habitat, nor the Start Printed Page 136 essential features of critical habitat, as a result. The referenced paper specifically mentions that red lionfish do not prey on Nassau grouper, and therefore that effect was considered negligible.

Comments on the Essential Features

Comment 6: One commenter requested that the phrase “close proximity” in the description of the recruitment and developmental habitat essential feature be expanded upon in the final rule to increase public and federal agency awareness. The commenter also provided a copy of a peer-reviewed publication (Blincow et al., 2020) that could be used to inform movement and range estimates.

Response: In our description of the essential features, we proposed to describe the intermediate hardbottom and seagrass areas in “close proximity” to the nearshore shallow subtidal marine nursery areas, and the offshore linear and patch reefs in “close proximity” to intermediate hardbottom and seagrass areas. We use the term “close proximity” to account for the high variability in habitat configurations, oceanographic conditions, and the movement patterns of individual Nassau grouper, which also vary across developmental stages, rather than prescribe a particular distance. We find that this term allows us to appropriately describe and include habitat components that are needed and accessible to maturing individual groupers as they recruit and progress to successive developmental stages and the bottom types that support each stage of development and to exclude areas that may have the prescribed bottom characteristics, but which are isolated from areas that support other developmental stages. As per the regulations for designating critical habitat (50 CFR 424.12) the description outlined above is the appropriate level of specificity for the essential feature based on the available information for this species.

The peer-reviewed publication (Blincow et al., 2020) referenced by the commenter demonstrates a clear variability in depth use by Nassau grouper depending on the condition of the individual ( i.e., the relative health of the individual), but does not attempt to quantify the extent of daily movements. In addition, the referenced publication discusses movement patterns of Nassau grouper adults and does not include the juveniles that were discussed in the recruitment and developmental habitat essential feature. We therefore have retained the term “close proximity” in the description of the recruitment and development habitat essential feature as appropriate to prioritize the proximity of progressive ontogenetic habitats rather than the range movements of individual adults.

Comments on Critical Habitat Units

Comment 7: One commenter suggested that Florida Unit 1 be expanded farther north, while Florida Units 3 and 4 be expanded to include areas off of Boca Chica and Key West.

Response: The commenter did not provide any new supporting evidence as to why the Florida units should be expanded beyond a slightly different interpretation of the same maps that we considered. The areas identified as critical habitat include the benthic types listed in the recruitment and developmental habitat essential feature, as determined by an analysis of the best available benthic maps, and the areas suggested by the commenter do not include the necessary features. Specifically, the areas included in Florida Units 1, 3, and 4 comprise hard bottom habitat with a mosaic of benthic habitats including pavement, seagrass, and carbonate sand and rubble. The areas adjacent to these units that are suggested by the commenter do not include the benthic types we specified for this essential feature, as the sites had clear breaks of contiguous habitats ( e.g., seagrass, colonized hardbottom) that were discontinued at the specified critical habitat boundaries and are therefore not designated as critical habitat.

Comment 8: One commenter requested the expansion of the critical habitat designations around the oceanic islands of Desecheo, Mona, and Monito, off the west coast of Puerto Rico, to include all platform areas up to the 50 m (164 ft) depth contour. They provided peer-reviewed scientific literature to support the assertion that the unique characteristics of these islands require special consideration with regards to habitat use by Nassau grouper.