2013-31576. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for Chromolaena frustrata (Cape Sable Thoroughwort)

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 1552

AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

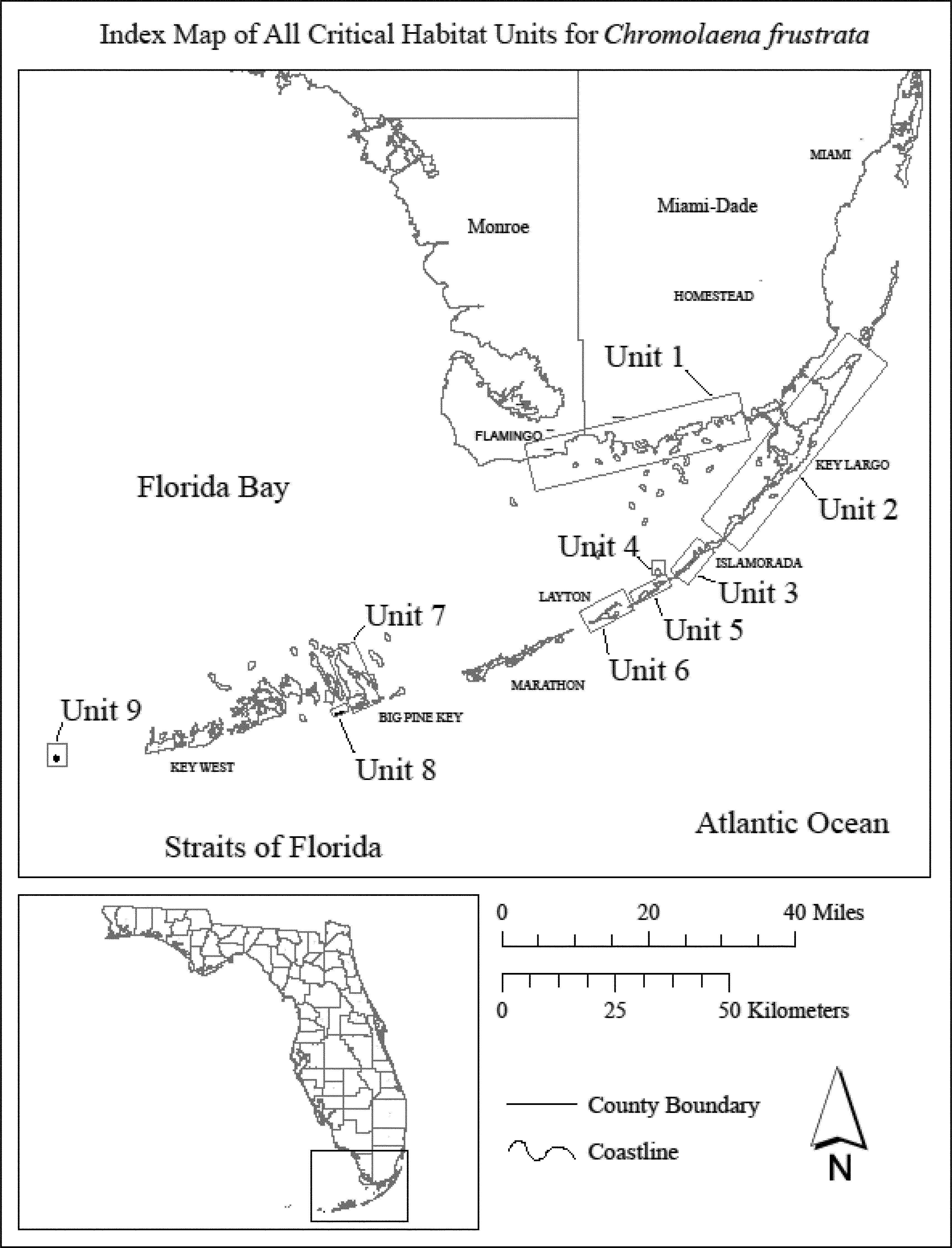

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), designate critical habitat for the Chromolaena frustrata (Cape Sable thoroughwort) under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). In total, approximately 10,968 acres (4,439 hectares) in Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties, Florida, fall within the boundaries of the critical habitat designation. The effect of this regulation is to designate critical habitat for this species under the Act for the conservation of the species.

DATES:

This rule is effective on February 7, 2014.

ADDRESSES:

This final rule is available on the Internet at http://www.regulations.gov and http://www.fws.gov/verobeach/. Comments and materials we received, as well as supporting documentation used in preparation of this rule, are available for public inspection at http://www.regulations.gov. All of the comments, materials, and documentation that we considered in this rulemaking are available by appointment, during normal business hours, at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, South Florida Ecological Services Office, 1339 20th Street, Vero Beach, FL 32960; by telephone 772-562-3909; or by facsimile 772-562-4288.

The coordinates, plot points, or both from which the maps are generated are included in the administrative record for this critical habitat designation and are available at http://www.regulations.gov,, Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2013-0029, and at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, South Florida Ecological Services Office at http://www.fws.gov/verobeach/ (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT). Any additional tools or supporting information that we developed for this critical habitat designation will also be available at the Fish and Wildlife Service Web site and Field Office set out above, and may also be included in the preamble of this rule and at http://www.regulations.gov.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Larry Williams, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, South Florida Ecological Services Office, 1339 20th Street, Vero Beach, FL 32960; telephone 772-562-3909; or facsimile 772-562-4288. If you use a use a telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD), call the Federal Information Relay Service (FIRS) at 800-877-8339.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. Under section 4(a)(3) of the Endangered Species Act (Act), when we determine that a species is endangered or threatened, we are required to designate critical habitat, to the maximum extent prudent and determinable. Designations of critical habitat can only be completed by issuing a rule.

We published our determination for Chromolaena frustrata as an endangered species on October 24, 2013 (78 FR 63796). On October 11, 2012 (77 FR 61836), we published in the Federal Register a proposed critical habitat designation for C. frustrata.

The areas we are designating in this rule constitute our current best assessment of the areas that meet the definition of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata. In total, we are designating approximately 10,968 acres (4,439 hectares), in nine units, as critical habitat for C. frustrata.

We have prepared an economic analysis of the designation of critical habitat. Section 4(b)(2) of the Act states that the Secretary shall designate critical habitat on the basis of the best scientific data, after taking into consideration the economic impact, national security impact, and any other relevant impact of specifying any particular areas as critical habitat. In accordance with section 4(b)(2) of the Act, we have prepared an analysis of the economic impacts of the critical habitat designation and related factors. We announced the availability of the draft economic analysis (DEA) in the Federal Register on July 8, 2013 (78 FR 40669), and sought comments from the public. We have incorporated the comments and have completed the final economic analysis (FEA) concurrently with this final designation.

Peer review and public comment. We sought comments from seven independent specialists to ensure that our designation is based on scientifically sound data, assumptions, and analyses. We obtained review from three knowledgeable individuals with scientific expertise to review our technical assumptions and analysis, and to determine whether or not we had used the best available information. These peer reviewers generally concurred with our methods and conclusions, and they provided additional information, clarifications, and suggestions to improve this final rule. Information we received from peer review is incorporated in this final designation. We considered all comments and information we received from the public during the comment periods.

Previous Federal Actions

On October 11, 2012, we published a proposed rule to list Chromolaena frustrata under the Act (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) and designate critical habitat for C. frustrata (77 FR 61836). All Federal actions related to protection under the Act for this species, prior to October 11, 2012, are outlined in the preamble to the proposed rule. On July 8, 2013 (78 FR 40669), we reopened the comment period on the proposed rule and announced the availability of the draft economic analysis for the proposed critical habitat designation.

Summary of Comments and Recommendations

We requested that the public submit written comments on the proposed designation of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata during two comment periods. The first comment period opened with the publication of the proposed rule on October 11, 2012, and closed on December 10, 2012 (77 FR 61836). The second comment period opened with the document published on July 8, 2013 (78 FR 40669), that made available and requested public comments on the draft economic analysis of the proposed critical habitat designation and that reopened the public comment period on the proposed listing and critical habitat designation. For that second comment period, we accepted public comments from July 8, 2013, through August 7, 2013 (78 FR 40669). We also contacted appropriate Federal, State, and local agencies; scientific organizations; and other interested parties and invited them to comment on the proposed rule and draft economic analysis during these comment periods. In addition, in October 2012, we published a total of six legal public notices on the proposed rule in the areas of south Florida affected by the designation. We did not receive any requests for a public hearing during either comment period.Start Printed Page 1553

The October 11, 2012, proposed rule contained both the proposed listing of Chromolaena frustrata, Consolea corallicola, and Harrisia aboriginum, as well as the proposed designation of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata. Therefore, we received combined comments from the public on both actions. However, in this final rule, we address only those comments that apply to the designation of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata. During the first comment period, we received one letter directly commenting on the proposed critical habitat designation for Chromolaena frustrata. During the second comment period, we received one letter commenting on the proposed critical habitat designation.

All substantive information provided during the comment periods specifically relating to the proposed critical habitat designation for Chromolaena frustrata is addressed in the following summary and incorporated into this final rule as appropriate.

Peer Reviewer Comments

In accordance with our peer review policy published on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34270), we solicited expert opinions from seven knowledgeable individuals with scientific expertise that included familiarity with the species, the geographic region in which the species occurs, and conservation biology principles. Of those, three reviewers were experts on Chromolaena frustrata. We received responses from six of the peer reviewers including the experts on C. frustrata.

We reviewed all comments we received from the peer reviewers for substantive issues and new information regarding critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata. The peer reviewers generally concurred with our methods and conclusions and provided additional information, clarifications, and suggestions to improve this final critical habitat rule. Two peer reviewer comments are addressed in the following summary and incorporated into this final rule as appropriate.

(1) Comment: One peer reviewer indicated that rockland hammock does not occur in the coastal area of Everglades National Park (ENP). Instead, the commenter indicated the habitat in ENP where Chromolaena frustrata occurs should be classified as coastal hardwood hammock.

Our Response: Unit 1 (ENP) includes the areas and habitats referred to by the peer reviewer. The Service misapplied the name rockland hammock to the coastal hardwood hammock habitat (sensu Rutchey et al. 2006, p. 21) present within this unit. While similar in overall vegetation structure and disturbance regime, coastal hardwood hammock differs from rockland hammock in that it develops on elevated marl ridges with a thin layer of organic matter, as opposed to exposed limestone. The plant species composition of coastal hardwood hammock also differs somewhat from rockland hammock. These clarifications have been incorporated in the “Habitat” and “Distribution and Range” sections; and the Physical or Biological Features and Primary Constituent Elements for Chromolaena frustrata sections of this final rule. No changes were made to the unit boundaries because of this change in classification of the habitat.

(2) Comment: One peer reviewer indicated that coastal berm does not occur within the critical habitat proposed in ENP.

Our Response: The Service incorrectly thought that coastal berm habitat was present in Unit 1 (ENP). ENP staff confirmed that this is not the case. We removed references to coastal berm in Unit 1 in the unit description.

Comments From States

The proposed designation of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata occurs only in the State of Florida. The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS), Florida Forest Service, an agency that administers a grant program for imperiled plant species in Florida, provided only peer review comments on the proposed rule. The FDACS, Division of Plant Industry, the agency responsible for permits for collecting or harvesting State-protected plants in Florida, was notified by Service staff of the reopening of the comment period and notice of availability of the economic analysis, and that Division provided official comments supporting the designation of critical habitat for the plant.

Public Comments

(3) Comment: One commenter indicated that critical habitat designation for Chromolaena frustrata should explicitly include both occupied and unoccupied habitat areas that will buffer this species from climate change, and the Service should explain how these areas will be sufficient to ensure the species' persistence in the face of ongoing sea-level rise.

Our Response: The sea-level rise projections discussed under Factor E (see the proposed listing rule, 77 FR 61836) suggest that much of the proposed critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata could be lost to sea-level rise by 2100 if high-end projections approaching 6.6 feet (ft) (2 meters (m)) become a reality. This critical habitat designation for C. frustrata includes both occupied and unoccupied habitat at the highest elevation areas available within the species' historical range in the Florida Keys, so as to provide suitable upland habitat for the longest possible time before these areas are lost to sea-level rise. The highest sea-level rise of 5.9 ft (1.8 m) forecast for this area based on inundation modeling indicates the higher elevation areas of Key Largo, Upper Matecumbe, and Lignumvitae Key will continue to support upland habitats to at least 2100. However, all other areas in the Florida Keys and areas that currently support C. frustrata in ENP may be lost to sea-level rise by 2100.

In the next 50 to 100 years, in order for Chromolaena frustrata to survive, reintroduction to suitable higher elevation sites outside of its historical range may be the only available option. However, the best available science is not able to project future locations of suitable habitat for C. frustrata on the Florida mainland, which will also be affected by sea-level rise within and outside the historical range of the plant. The range of sea-level rise projections coupled with the lack of models specific to the areas and habitats does not support identification of unoccupied areas of critical habitat for this species solely on the basis of the effects of climate change on the Florida mainland at this time.

(4) Comment: One commenter indicated there are ample precedent, legal authority, and conservation imperatives for the Service to identify and designate unoccupied inland habitat for the plant to buffer it from the effects of sea-level rise and increasing storm surge.

Our Response: As stated in the response to Comment 3, above, we agree that considerations should include whether unoccupied areas (including areas outside the historical range) are essential to the conservation of the species, including areas less vulnerable to sea-level rise and storm surge impacts in the future. We have endeavored to designate areas of habitat to serve these functions for Chromolaena frustrata, within the bounds of the best available science. We selected areas of higher elevation within suitable habitat on each of the Florida Keys within the species' historical range with the expectation that these areas will be less vulnerable to storm surge and will retain the physical and biological features that support Chromolaena frustrata for a longer duration than Start Printed Page 1554many of the sites where the species exists currently. However, the best available science is not able to project future locations of suitable habitat for the species on the Florida mainland. Therefore, we did not designate unoccupied critical habitat solely on the basis of the effects of climate change.

Summary of Changes From Proposed Rule

Based on information we received in comments regarding the habitats that support Chromolaena frustrata, we refined our description of the primary constituent elements to more accurately reflect the habitat needs of the species. Specifically, habitats in ENP previously identified as rockland hammock were reclassified as coastal hardwood hammock to account for the different substrate on which these communities develop and subtle differences in species composition. No adjustments to the unit boundaries were needed as a result of this change. A change, made throughout the final rule, was the clarification that plant species in each habitat community may be present, but are not limited to those native species listed in the vegetation description.

We corrected errors in the critical habitat unit acreage that were due to rounding errors. These rounding errors resulted in changes of no more than 1 to 3 ac (0 to 1 ha) in any given unit. We also corrected a calculation error in the acreage of Unit 1 (ENP). This error was due to a miscalculation of the unit size. In the proposed rule, we reported the area of Unit 1 as 3,768 ac (1,525 ha). In the final rule, we report the correct area, which is 6,166 ac (2,495 ha). The Service coordinated this change with ENP, who expressed no concern with the change, as their review focused on the mapped boundaries in the proposed rule, which correctly represented the proposed designated habitat. No adjustments to the unit boundaries were needed as a result of this change. This change does not affect the outcome of economic analysis for the proposed unit designations concerning the projection of incremental effects, as it is based on the consultation history in the mapped area, not the acres. The rounding error corrections and the unit 1 acreage correction results in the total acreage of designated critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata to be 10,968 ac (4,439 ha).

Summary of Biological Status for Chromolaena frustrata

For more information on Chromolaena frustrata' s taxonomy, life history, habitat, population descriptions, and factors affecting the species, refer to the proposed rule published in the Federal Register on October 11, 2012 (77 FR 61836).

We have evaluated the biological status of this species and threats affecting its continued existence. Our assessment, as summarized immediately below, is based upon the best available scientific and commercial data and the opinion of the species experts.

Chromolaena frustrata (Family: Asteraceae) is a perennial herbaceous plant. Mature plants are 5.9 to 9.8 inches (in) (15 to 25 centimeters (cm)) tall with erect stems. The blue to lavender flowers are borne in heads, usually in clusters of two to six. Flowers are produced mostly in the fall, though sometimes year round (Nesom 2006, pp. 544-545).

Taxonomy

Chromolaena frustrata was first reported by Chapman, from the Florida Keys in 1886, naming it Eupatorium heteroclinium (Chapman 1889, p. 626). Synonyms include Eupatorium frustratum B.L. Robinson and Osmia frustrata (B.L. Robinson) Small.

Climate

The climate of south Florida where Chromolaena frustrata occurs is classified as tropical savanna and is characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons, a monthly mean temperature above 64.4 degrees Fahrenheit (°F) (18 degrees Celsius (°C)) in every month of the year, and annual rainfall averaging 30 to 60 in (75 to 150 cm) (Gabler et al. 1994, p. 211).

Habitat

Chromolaena frustrata grows in open canopy habitats in coastal berms and coastal rock barrens, and in semi-open to closed canopy habitats, including buttonwood forests, coastal hardwood hammocks, and rockland hammocks. C. frustrata is often found in the shade of associated canopy and subcanopy plant species; these canopies buffer C. frustrata from full exposure to the sun (Bradley and Gann 1999, p. 37).

Detailed descriptions of coastal berm, coastal rock barren, rockland hammock, and buttonwood forest are presented in the proposed listing rule for Chromolaena frustrata, Consolea corallicola, and Harrisia aboriginum (77 FR 61836; October 11, 2012). Peer reviewers provided new information identifying coastal hardwood hammock as the community type supporting Chromolaena frustrata in ENP and identified associated species found in buttonwood forest in ENP. We include a full description of the coastal hardwood hammock and a revised description of the buttonwood forest communities below.

Coastal Hardwood Hammock

Coastal hardwood hammock that supports Chromolaena frustrata in ENP is a species-rich, tropical hardwood forest. Though similar to rockland hammock in most characteristics, coastal hardwood hammock develops on a substrate consisting of elevated marl ridges with a very thin organic layer (Sadle 2012a, pers. comm.). Marl is an unconsolidated sedimentary rock or soil consisting of clay and lime. The plant species composition of coastal hardwood hammocks also differs somewhat from that of rockland hammock. Typical tree and shrub species may include, but are not limited to, Capparis flexuosa (bayleaf capertree), Coccoloba diversifolia (pigeon plum), Piscidia piscipula (Jamaican dogwood), Sideroxylon foetidissimum (false mastic), Eugenia foetida (Spanish stopper), Swietenia mahagoni (West Indies mahogany), Ficus aurea (strangler fig), Sabal palmetto (cabbage palm), Eugenia axillaris (white stopper), Zanthoxylum fagara (wild lime), Sideroxylon celastrinum (saffron plum), and Colubrina arborescens (greenheart) (Rutchey et al. 2006, p. 21). Herbaceous species in coastal hardwood forest may include, but are not limited to, Acanthocereus tetragonus (barbed wire or triangle cactus), Alternanthera flavescens (yellow joyweed), Batis maritima (saltwort or turtleweed), Borrichia arborescens (tree seaside oxeye), Borrichia frutescens (bushy seaside oxeye), Caesalpinia bonduc (grey nicker), Capsicum annuum (bird pepper), Galactia striata (Florida hammock milkpea), Heliotropium angiospermum (scorpion's tail), Passiflora suberosa (corkystem passionflower), Rivina humilis (pigeonberry), Salicornia perennis (perennial glasswort), Sesuvium portulacastrum (seapurslane), and Suaeda linearis (sea blite). Ground cover is often limited in closed canopy areas and abundant in areas where canopy disturbance has occurred or where this community intergrades with buttonwood forest (Sadle 2012a, pers. comm.).

The sparsely vegetated edges or interior portions of rockland and coastal hardwood hammock where the canopy is open are the areas that have light levels sufficient to support Chromolaena frustrata. However, the dynamic nature of the habitat means that areas not currently open may become open in the future as a result of canopy disruption from hurricanes, Start Printed Page 1555while areas currently open may develop more dense canopy over time, eventually rendering that portion of the hammock unsuitable for C. frustrata.

Buttonwood Forest

Forests dominated by buttonwood often exist in upper tidal areas, especially where mangrove swamp transitions to rockland or coastal hardwood hammock. These buttonwood forests have canopy dominated by Conocarpus erectus (buttonwood) and often have an understory dominated by Borrichia frutescens, Lycium carolinianum (Christmasberry), and Limonium carolinianum (sea lavender) (Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) 2010d, p. 4). In ENP, the species most frequently observed in association with Chromolaena frustrata are Capparis flexuosa, Borrichia frutescens, Alternanthera flavescens, Rivina humilis, Sideroxylon celastrinum, Heliotropium angiospermum, Eugenia foetida, Batis maritima, Acanthocereus tetragonus, and Sesuvium portulacastrum (Sadle 2012a, pers. comm.).

Temperature, salinity, tidal fluctuation, substrate, and wave energy influence the size and extent of buttonwood forests (FNAI 2010e, p. 3). Buttonwood forests often grade into salt marsh, coastal berm, rockland hammock, coastal hardwood hammock, and coastal rock barren (FNAI 2010d, p. 5).

Distribution and Range

Chromolaena frustrata is endemic to the southern tip of Florida and the Florida Keys. It occurs within coastal berm, coastal rock barrens, coastal hardwood hammock, rockland hammock, and buttonwood forest habitat. The estimated rangewide population was 6,500 to 7,500 plants when the eight known populations were last surveyed (Bradley and Gann 2004, pp. 3-6; Sadle 2012a, pers. comm.; Duquesnel 2012, pers. comm.). Four of eight extant C. frustrata populations consist of fewer than 100 individuals. These populations may not be viable in the long term due to their small number of individuals.

Chromolaena frustrata was historically known from Monroe County, both on the Florida mainland and the Florida Keys, and in Miami-Dade County along Florida Bay in ENP (Bradley and Gann 1999, p. 36). In the Florida Keys, C. frustrata was observed historically on Big Pine Key, Boca Grande Key, Fiesta Key, Key Largo, Key West, Knight's Key, Lignumvitae Key, Long Key, Upper Matecumbe Key, and Lower Matecumbe Key (Bradley and Gann 1999, p. 36; Bradley and Gann 2004, pp. 4-7). Chromolaena frustrata has been extirpated from half of the islands where it occurred in the Florida Keys, but appears to occupy its historical distribution in ENP. Although remaining C. frustrata populations occur mostly within public conservation lands, threats to the species from a wide array of natural and anthropogenic sources still remain. Habitat loss and modification, recreation impacts, and competition from nonnative plant species still exist in all remaining populations. Additionally, much of the species' habitat is projected to be lost to sea-level rise over the next century.

In ENP, 11 Chromolaena frustrata subpopulations supporting approximately 1,600 to 2,600 plants occur in buttonwood forests and coastal hardwood hammocks from the Coastal Prairie Trail near the southern tip of Cape Sable to Madeira Bay (Sadle 2007 and 2012b, pers. comm.).

In the Florida Keys, Chromolaena frustrata is now known only from Upper Matecumbe Key, Lower Matecumbe Key, Lignumvitae Key, Long Key, Big Munson Island, and Boca Grande Key (Bradley and Gann 2004, pp. 3-4). It no longer exists on Key Largo, Big Pine Key, Fiesta Key, Knight's Key, or Key West (Bradley and Gann 2004, pp. 4-6).

Reproductive Biology and Genetics

The reproductive biology and genetics of Chromolaena frustrata have received little study. Fresh C. frustrata seeds show a germination rate of 65 percent, but germination rates decrease to 27 percent after the seeds are subjected to freezing, suggesting that long-term seed storage may present difficulties (Kennedy et al. 2012, pp. 40, 50-51). While there have been no studies on the reproductive biology of C. frustrata, we can draw some generalizations from other species of Chromolaena, which reproduce sexually. New plants originate from seeds. Pollinators are likely to be generalists, such as butterflies, bees, flies, and beetles. Seed dispersal is largely by wind (Lakshmi et al. 2011, p. 1).

Population Demographics

Chromolaena frustrata is relatively a short-lived plant; therefore it must successfully reproduce more often than a long-lived species to maintain populations. C. frustrata populations are demographically unstable, experiencing sudden steep declines due to the effects of hurricanes and storm surges. However, the species appears to be able to rebound at affected sites within a few years (Bradley 2009, pers. comm.). The large population observed at Big Munson Island in 2003 likely resulted from thinning of the rockland hammock canopy caused by Hurricane Georges in 1998 (Bradley and Gann 2004, p. 4). Populations that are subject to wide demographic fluctuations are generally more vulnerable to random extinction events and negative consequences arising from small populations, such as genetic bottlenecks.

Critical Habitat

Background

Critical habitat is defined in section 3 of the Act as:

(1) The specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed in accordance with the Act, on which are found those physical or biological features

(a) Essential to the conservation of the species, and

(b) Which may require special management considerations or protection; and

(2) Specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed, upon a determination that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species.

Conservation, as defined under section 3 of the Act, means to use and the use of all methods and procedures that are necessary to bring an endangered or threatened species to the point at which the measures provided pursuant to the Act are no longer necessary. Such methods and procedures include, but are not limited to, all activities associated with scientific resources management such as research, census, law enforcement, habitat acquisition and maintenance, propagation, live trapping, and transplantation, and, in the extraordinary case where population pressures within a given ecosystem cannot be otherwise relieved, may include regulated taking.

Critical habitat receives protection under section 7 of the Act through the requirement that Federal agencies ensure, in consultation with the Service, that any action they authorize, fund, or carry out is not likely to result in the destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat. The designation of critical habitat does not affect land ownership or establish a refuge, wilderness, reserve, preserve, or other conservation area. Such designation does not allow the government or public to access private lands. Such designation does not require implementation of restoration, recovery, or enhancement measures by non-Start Printed Page 1556Federal landowners. Where a landowner requests Federal agency funding or authorization for an action that may affect a listed species or critical habitat, the consultation requirements of section 7(a)(2) of the Act would apply, but even in the event of a destruction or adverse modification finding, the obligation of the Federal action agency and the landowner is not to restore or recover the species, but to implement reasonable and prudent alternatives to avoid destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat.

Under the first prong of the Act's definition of critical habitat, areas within the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it was listed are included in a critical habitat designation if they contain physical or biological features (1) which are essential to the conservation of the species and (2) which may require special management considerations or protection. For these areas, critical habitat designations identify, to the extent known using the best scientific and commercial data available, those physical or biological features that are essential to the conservation of the species (such as space, food, cover, and protected habitat). In identifying those physical or biological features within an area, we focus on the principal biological or physical constituent elements (primary constituent elements such as roost sites, nesting grounds, seasonal wetlands, water quality, tide, soil type) that are essential to the conservation of the species. Primary constituent elements are those specific elements of the physical or biological features that provide for a species' life-history processes and are essential to the conservation of the species.

Under the second prong of the Act's definition of critical habitat, we can designate critical habitat in areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed, upon a determination that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. For example, an area currently occupied by the species but that was not occupied at the time of listing may be essential to the conservation of the species and may be included in the critical habitat designation. We designate critical habitat in areas outside the geographical area occupied by a species only when a designation limited to its range would be inadequate to ensure the conservation of the species.

Section 4 of the Act requires that we designate critical habitat on the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available. Further, our Policy on Information Standards Under the Endangered Species Act (published in the Federal Register on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34271)), the Information Quality Act (section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2001 (Pub. L. 106-554; H.R. 5658)), and our associated Information Quality Guidelines provide criteria, establish procedures, and provide guidance to ensure that our decisions are based on the best scientific data available. They require our biologists, to the extent consistent with the Act and with the use of the best scientific data available, to use primary and original sources of information as the basis for recommendations to designate critical habitat.

When we are determining which areas should be designated as critical habitat, our primary source of information is generally the information developed during the listing process for the species. Additional information sources may include the recovery plan for the species, articles in peer-reviewed journals, conservation plans developed by States and counties, scientific status surveys and studies, biological assessments, other unpublished materials, or experts' opinions or personal knowledge.

Habitat is dynamic, and species may move from one area to another over time. We recognize that critical habitat designated at a particular point in time may not include all of the habitat areas that we may later determine are necessary for the recovery of the species. For these reasons, a critical habitat designation does not signal that habitat outside the designated area is unimportant or may not be needed for recovery of the species. Areas that are important to the conservation of the species, both inside and outside the critical habitat designation, will continue to be subject to: (1) Conservation actions implemented under section 7(a)(1) of the Act, (2) regulatory protections afforded by the requirement in section 7(a)(2) of the Act for Federal agencies to insure their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species, and (3) section 9 of the Act's prohibitions on taking any individual of the species, including taking caused by actions that affect habitat. Federally funded or permitted projects affecting listed species outside their designated critical habitat areas may still result in jeopardy findings in some cases. These protections and conservation tools will continue to contribute to recovery of this species. Similarly, critical habitat designations made on the basis of the best available information at the time of designation will not control the direction and substance of future recovery plans, habitat conservation plans (HCPs), or other species conservation planning efforts if new information available at the time of these planning efforts calls for a different outcome.

Physical or Biological Features

In accordance with section 3(5)(A)(i) and 4(b)(1)(A) of the Act and regulations at 50 CFR 424.12, in determining which areas within the geographical area occupied by the species at the time of listing to designate as critical habitat, we consider the physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species and which may require special management considerations or protection. These include, but are not limited to:

(1) Space for individual and population growth and for normal behavior;

(2) Food, water, air, light, minerals, or other nutritional or physiological requirements;

(3) Cover or shelter;

(4) Sites for breeding, reproduction, or rearing (or development) of offspring; and

(5) Habitats that are protected from disturbance or are representative of the historical, geographical, and ecological distributions of a species.

We derived the specific physical or biological features essential for Chromolaena frustrata from studies of this species' habitat, ecology, and life history as described in the Critical Habitat section of the proposed rule to designate critical habitat published in the Federal Register on October 11, 2012 (77 FR 61836), and in the information presented below. We have determined that physical or biological features presented below are required for the conservation of C. frustrata. One change to these features in this final determination from the proposed rule is a result of the peer review process: coastal hardwood hammock has been added to the plant communities known for C. frustrata because it describes the plant community more accurately in ENP (Sadle 2012a, pers. comm.). We also include new information about reproductive patterns in the genus Chromolaena.

Space for Individual and Population Growth

Plant Community and Competitive Ability. Chromolaena frustrata occurs in communities classified as coastal berms, coastal rock barrens, buttonwood forests, coastal hardwood hammocks, and rockland hammocks restricted to tropical south Florida and the Florida Start Printed Page 1557Keys. These communities and their associated native plant species are provided in the Status Assessment for Chromolaena frustrata, Consolea corallicola, and Harrisia aboriginum section of the proposed rule (77 FR 61836) and the newly added information on coastal hardwood hammocks and buttonwood forests in this final rule. Therefore, we identify upland habitats consisting of coastal berms, coastal rock barrens, buttonwood forests, coastal hardwood hammocks, and rockland hammocks restricted to tropical south Florida and the Florida Keys to be a physical or biological feature for Chromolaena frustrata.

Food, Water, Air, Light, Minerals, or Other Nutritional or Physiological Requirements

Climate (temperature and precipitation). The climate of south Florida where Chromolaena frustrata occurs is characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons, a monthly mean temperature above 64.4 °F (18 °C) in every month of the year, and annual rainfall averaging 30 to 60 in (75 to 150 cm) (Gabler et al. 1994, p. 211). Freezes can occur in the winter months, but are very infrequent at this latitude in Florida.

Soils. Substrates supporting Chromolaena frustrata for anchoring or nutrient absorption vary depending on the habitat and location and include marl (an unconsolidated sedimentary rock or soil consisting of clay and lime) (Sadle 2008 and 2012a, pers. comm.); soils consisting of covering limestone; exposed bare limestone rock or with a thin layer of leaf litter or highly organic soil (Bradley and Gann 1999, p. 37; FNAI 2010d, p. 1); or loose sediment formed by a mixture of coarse sand, shell fragments, pieces of coralline algae, and other coastal debris (FNAI 2010a, p. 1). The natural process giving rise to coastal rock barren is not known, but as it occurs on sites where the thin layer of organic soil over limestone bedrock is missing, coastal rock barren may have formed by soil erosion following destruction of the plant cover by fire or storm surge (FNAI 2010c, p. 2). Therefore, we identify substrates derived from calcareous sand, limestone, or marl that provide anchoring and nutritional requirements to be a physical or biological feature for Chromolaena frustrata.

Hydrology. The species requires coastal berms and coastal rock barrens habitats that occur above the daily tidal range, but are subject to flooding by seawater during extreme tides and storm surge. Rockland hammock and coastal hardwood hammock occur on high ground that does not regularly flood, but they are often dependent upon a high water table to keep humidity levels high, and they can be inundated during storm surges (FNAI 2010d, p. 1). Therefore, we identify habitats inundated by storm surge or tidal events at a frequency needed to limit plant species competition while not creating too high of a saline condition to be a physical or biological feature for Chromolaena frustrata.

Cover or Shelter

Chromolaena frustrata occurs in open canopy and semi-open to closed canopy habitats and thrives in areas of moderate sun exposure (Bradley and Gann 1999, p. 37). The amount and frequency of such microsites varies by habitat type and time elapsed since the last disturbance. In rockland and coastal hardwood hammocks, suitable microsites will often be found near the hammock edge where the canopy is most open. However, the species has been observed to spread into the hammocks when canopy cover is reduced by hurricane damage to canopy trees. More open communities (e.g., coastal berm, buttonwood, and salt marsh ecotone) provide more abundant and temporally consistent suitable habitat than communities capable of establishing a dense canopy (e.g., rockland and coastal hardwood hammock). Therefore, we identify habitats that have a vegetation composition and structure that allows for adequate sunlight and space for individual growth and population expansion to be a physical or biological feature for Chromolaena frustrata.

Sites for Breeding, Reproduction, or Rearing (or Development) of Offspring

While there have been no studies on the reproductive biology of Chromolaena frustrata, we can draw some generalizations from other species of Chromolaena, which reproduce sexually. Pollinators are likely to be generalists, such as butterflies, bees, flies, and beetles. New plants originate from seeds and seeds dispersal is largely by wind (Lakshmi et al. 2011, p. 1).

The sparsely vegetated edges or interior portions opened by canopy disruption are the areas of rockland and coastal hardwood hammock that have light levels sufficient to support Chromolaena frustrata. However, the dynamic nature of the habitat means that areas not currently open may become open in the future as a result of canopy disruption from hurricanes, while areas currently open may develop more dense canopy over time, eventually rendering that portion of the hammock unsuitable for C. frustrata. Therefore, we identify habitats that have disturbance regimes, including hurricanes, and infrequent inundation events that saturate the substrate and maintain the habitat suitability to be physical or biological features for Chromolaena frustrata.

Habitats Protected From Disturbance or Representative of the Historical, Geographic, and Ecological Distributions of the Species

Chromolaena frustrata continues to occur in habitats that are protected from human-generated disturbances and are representative of the species' historical, geographical, and ecological distribution although its range has been reduced. The species is still found in all of its representative plant communities: rock barrens, coastal berms, buttonwood forest, coastal hardwood hammocks, and rockland hammocks. In addition, representative communities are located on Federal, State, local, and private conservation lands that implement conservation measures benefitting the species. The species requires habitat of sufficient size and connectivity that can support species growth, distribution and population expansion.

Primary Constituent Elements for Chromolaena frustrata

Under the Act and its implementing regulations, we are required to identify the physical or biological features essential to the conservation of Chromolaena frustrata in areas occupied at the time of listing, focusing on the features' primary constituent elements (PCEs). Primary constituent elements are those specific elements of the physical or biological features that provide for a species' life-history processes and are essential to the conservation of the species.

Based on our current knowledge of the physical or biological features and habitat characteristics required to sustain the species' life-history processes, we determine that the PCEs specific to Chromolaena frustrata are:

(1) Areas of upland habitats consisting of coastal berm, coastal rock barren, coastal hardwood hammock, rockland hammocks, and buttonwood forest.

(a) Coastal berm habitat that contains:

(i) Open to semi-open canopy, subcanopy, and understory; and

(ii) Substrate of coarse, calcareous, storm-deposited sediment.

(b) Coastal rock barren (Keys cactus barren, Keys tidal rock barren) habitat that contains:

(i) Open to semi-open canopy and understory; and

(ii) Limestone rock substrate.Start Printed Page 1558

(c) Coastal hardwood hammock habitat occurring in Everglades National Park that contains:

(i) Canopy gaps and edges with an open to semi-open canopy, subcanopy, and understory; and

(ii) Substrate of marl covered with a thin layer of highly organic soil.

(d) Rockland hammock habitat that contains:

(i) Canopy gaps and edges with an open to semi-open canopy, subcanopy, and understory; and

(ii) Substrate with a thin layer of highly organic soil, marl, humus, or leaf litter on top of the underlying limestone.

(e) Buttonwood forest habitat that contains:

(i) Open to semi-open canopy and understory; and

(ii) Substrate with calcareous marl muds, calcareous sands, or limestone rock.

(2) Plant communities of predominately native vegetation with either no invasive, nonnative species or with low enough quantities of nonnative, invasive plant species to have minimal effect on the survival of Chromolaena frustrata.

(3) A disturbance regime, due to the effects of strong winds or saltwater inundation from storm surge or infrequent tidal inundation, that creates canopy openings in coastal berm, coastal rock barren, coastal hardwood hammock, rockland hammocks, and buttonwood forest.

(4) Habitats that are connected and of sufficient area to sustain viable populations in coastal berm, coastal rock barren, coastal hardwood hammock, rockland hammocks, and buttonwood forest.

Special Management Considerations or Protections

When designating critical habitat, we assess whether the specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species at the time of listing contain features that are essential to the conservation of the species and which may require special management considerations or protection.

Special management considerations or protection are necessary throughout the critical habitat areas to avoid further degradation or destruction of the habitat that contains those features essential for the conservation of the species. The primary threats to the physical or biological features that Chromolaena frustrata depends on include: (1) Habitat destruction and modification by development; (2) competition with nonnative, invasive plant species that changes the habitat composition and structure; (3) wildfire that destroys habitat; (4) hurricanes and storm surge, if too frequent or severe destroy or modify habitat making it unsuitable; and (5) sea-level rise that changes the habitat to a more saline environment. Some of these threats can be addressed by special management considerations or protection while others (e.g., sea-level rise, hurricanes) are beyond the control of landowners and managers. However, while landowners or land managers may not be able to control all the threats, they may be able to address the results of the threats to the habitats.

Management activities that could ameliorate these threats include the monitoring and minimizing recreational activities impacts, nonnative species control, and protection from development. Precautions are needed to avoid the inadvertent trampling of Chromolaena frustrata in the course of management activities and public use. Development of recreation facilities or programs should avoid impacting these habitats directly or indirectly. Ditching and filling should be avoided because they alter the hydrology and species composition of these habitats. Sites that have shown increasing encroachment of woody species over time may require efforts to maintain the open nature of the habitat, which favors these species. Nonnative species control programs are needed to reduce competition and prevent habitat degradation. The reduction of these threats will require the implementation of special management actions within each of the critical habitat areas identified in this rule. All critical habitat requires active management to address the ongoing threats listed.

In summary, we find that each of the areas we are designating as critical habitat contain features essential to the conservation of Chromolaena frustrata that may require special management considerations or protection to ensure conservation of the species. These special management considerations and protections are required to preserve and maintain the essential features provided to C. frustrata by the ecosystems upon which it depends. A more detailed discussion of these threats is presented in the proposed rule under “Summary of Factors Affecting the Species” (77 FR 61836; October 11, 2012).

Criteria Used To Identify Critical Habitat

As required by section 4(b)(2) of the Act, we used the best scientific data available to designate critical habitat. In accordance with the Act and our implementing regulations at 50 CFR 424.12(b) we review available information pertaining to the habitat requirements of the species and identify occupied areas at the time of listing that contain the features essential to the conservation of the species. If after identifying currently occupied areas, we determine that those areas are inadequate to ensure conservation of the species, in accordance with the Act and our implementing regulations at 50 CFR 424.12(e), we then consider whether designating additional areas—outside those currently occupied—are essential for the conservation of the species. In this rule, we are designating critical habitat in areas within the geographical area occupied by the species at the time of listing in 2013. We also are designating specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time of listing that were historically occupied, because we have determined that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. Sources of data for this analysis included the following:

(1) Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) population records and ArcGIS geographic information system (GIS) software to spatially depict the location and extent of documented populations of Chromolaena frustrata (FNAI 2012, pp. 1-17);

(2) Reports prepared by botanists with the Institute for Regional Conservation (IRC), National Park Service (NPS), and Florida Department Environmental Protection (FDEP). Some of these were funded by the Service, others were requested or volunteered by biologists with the NPS or FDEP;

(3) Historical records found in reports and associated voucher specimens housed at herbaria, all of which are also referenced in the above mentioned reports from the IRC and FNAI;

(4) Digitally produced habitat maps provided by NPS and Monroe County; and

(5) Aerial images of Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties. The presence of PCEs was determined through the use of GIS spatial data depicting the current habitat status. This habitat data for the Florida Keys were developed by Monroe County from 2006 aerial images, and ground conditions for many areas were checked in 2009. Habitat data for ENP were provided by the NPS. The areas that contain PCEs follow predictable landscape patterns and have a recognizable signature in the aerial photographs.

Four of the eight extant Chromolaena frustrata populations consist of fewer than 100 individuals; two others have fewer than 250 individuals. Small populations such as these populations that have limited distributions, are Start Printed Page 1559vulnerable to relatively minor environmental disturbances (Given 1994, pp. 66-76; Frankham 2005, pp. 135-136), and are subject to the loss of genetic diversity from genetic drift, the random loss of genes, and inbreeding (Ellstrand and Elam 1993, pp. 217-237; Leimu et al. 2006, pp. 942-952). Plant populations with lowered genetic diversity are more prone to local extinction (Barrett and Kohn 1991, pp. 4, 28). Smaller plant populations generally have lower genetic diversity, and lower genetic diversity may in turn lead to even smaller populations by decreasing the species' ability to adapt, thereby increasing the probability of population extinction (Newman and Pilson 1997, p. 360; Palstra and Ruzzante 2008, pp. 3428-3447). Because of the risks associated with small populations or limited distributions, the recovery of many rare plant species includes the creation of new sites or reintroductions to ameliorate these effects.

The current distribution of the Chromolaena frustrata is much reduced from its historical distribution. We anticipate that recovery will require continued protection of existing populations and habitat, as well as establishing populations in additional locations that more closely approximate its historical distribution in order to ensure there is adequate number of C. frustrata stable populations and that these populations occur over a wide geographic area within the species' historical range. This will help to ensure that catastrophic events, such as hurricanes or wildfire, would not simultaneously affect all known populations.

Areas Occupied at the Time of Listing

For the purpose of designating critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata, we defined the geographical area currently occupied by the species as required by section 3(5)(A)(i) of the Act. The occupied critical habitat units were delineated around documented extant populations. These units include the mapped extent of the population that contain one or more of the elements of the physical or biological features. We considered the following when identifying occupied areas of critical habitat:

(1) Space to allow for the successional nature of the occupied habitats (i.e., gain and loss of areas with sufficient light availability due to disturbance of the tree canopy driven by natural events such as inundation and hurricanes), and habitat transition or loss due to sea-level rise. In ENP, the distribution of Chromolaena frustrata is across a larger area than at any other single location. In the Florida Keys, the same criteria were used, but the size of the units is limited by the size of individual islands.

(2) Some areas will require special management to maintain connectivity of occupied habitat to allow for population expansion and connection with other populations. Isolation of populations can result in localized extinctions.

(3) Some areas will require special management to be able to support a higher density of the plant within the occupied space. These areas generally are habitats where some of the primary constituent elements have been lost through natural or human causes. These areas would help to off-set the anticipated loss and degradation of habitat occurring or expected from the effects of climate change (such as sea-level rise) or due to development.

After following the above criteria, we determined that occupied areas were not sufficient for the conservation of the species for the following reasons: (1) Restoring the species to its historical range and reducing its vulnerability to stochastic events such as hurricanes and storm surge requires reintroduction to areas where it occurred in the past but has since been extirpated; (2) providing increased connectivity for populations and areas for small populations to expand requires currently unoccupied habitat; and (3) reintroduction or assisted migration to reduce the vulnerability of the species to sea-level rise and storm surge requires higher elevation sites that currently are unoccupied by Chromolaena frustrata. Therefore, we looked to unoccupied areas that may be essential for the conservation of the species.

Areas Outside the Geographic Area Occupied at the Time of Listing

When designating critical habitat, we consider future recovery efforts and conservation of the species. Realizing that the current occupied habitat is not enough for the conservation and recovery of Chromolaena frustrata, we used habitat and historical occurrence data to identify unoccupied habitat essential for the conservation of the species as described below.

The unoccupied areas are essential for the conservation of the species because they:

(1) Represent the historical range of Chromolaena frustrata. C. frustrata has been extirpated from several locations where it was previously recorded. Of those areas found in reports, we are designating critical habitat only where there are well documented historical occurrences (i.e., Big Pine Key and Key Largo (Bradley and Gann 2004, pp. 4-6)). These areas still retain some or all the elements of the physical or biological features. Areas such as Fiesta Key and Knight's Key, which once supported populations of C. frustrata but no longer contain any PCEs and cannot be restored, are not included.

(2) Provide areas of sufficient size to support ecosystem processes for populations of Chromolaena frustrata. These areas are essential for the conservation of the species because they will provide areas for population expansion and growth. Large contiguous parcels of habitat are more likely to be resilient to ecological processes of disturbance and succession, and support viable populations of C. frustrata. The unoccupied areas selected were at least 30 ac (12.1 ha) or greater in size.

The amount and distribution of designated critical habitat will allow Chromoleana frustrata to:

(1) Maintain its existing distribution;

(2) Expand its distribution into historically occupied areas (needed to offset habitat loss and fragmentation);

(3) Use habitat depending on habitat availability (respond to changing nature of coastal habitat including occurring sea-level rise) and support genetic diversity;

(4) Increase the size of each population to a level where the threats of genetic, demographic, and normal environmental uncertainties are diminished; and

(5) Maintain its ability to withstand local or unit level environmental fluctuations or catastrophes.

When determining critical habitat boundaries within this final rule, we made every effort to avoid including developed areas such as lands covered by buildings, pavement, and other structures because such lands lack physical or biological features for Chromolaena frustrata. The scale of the maps we prepared under the parameters for publication within the Code of Federal Regulations may not reflect the exclusion of such developed lands. Any such lands inadvertently left inside critical habitat boundaries shown on the maps of this final rule have been excluded by text in the rule and are not designated as critical habitat. Therefore, a Federal action involving these lands will not trigger section 7 consultation with respect to critical habitat and the requirement of no adverse modification unless the specific action would affect the physical or biological features in the adjacent critical habitat.

The critical habitat designation is defined by the map or maps, as modified by any accompanying regulatory text, presented at the end of Start Printed Page 1560this document in the Regulation Promulgation section. We include more detailed information on the boundaries of the critical habitat designation in the preamble of this document. We will make the coordinates or plot points or both on which each map is based available to the public on http://www.regulations.gov at Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2013-0029, on our Internet site at http://www.fws.gov/verobeach/,, and at the field office responsible for the designation (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT, above).

Final Critical Habitat Designation

We are designating nine units as critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata. The critical habitat areas described below constitute our best assessment at this time of areas that meet the definition of critical habitat for C. frustrata. The nine units are: (1) Everglades National Park (ENP); (2) Key Largo; (3) Upper Matecumbe Key; (4) Lignumvitae Key; (5) Lower Matecumbe Key; (6) Long Key; (7) Big Pine Key; (8) Big Munson Island; and (9) Boca Grande Key. Land ownership within the critical habitat consists of Federal (70 percent), State (23 percent), and private and other (6 percent). Table 1 summarizes these units.

TABLE 1—Chromolaena frustrata Critical Habitat Units

Unit No. Unit Name Ownership Percent Acres Hectares Occupied 1 Everglades National Park Federal 100 6,166 2,495 yes. Total 100 6,166 2,495 2 Key Largo Federal 23 804 325 no. State 63 2,170 878 Private 13 457 185 Total 100 3,431 1,388 3 Upper Matecumbe Key State 34 24 10 yes. Private 66 45 18 Total 100 69 28 4 Lignumvitae Key State 100 180 73 yes. Total 100 180 73 5 Lower Matecumbe Key State 49 22 9 yes. Private 51 22 9 Total 100 44 18 6 Long Key State 73 151 61 yes. Private 27 57 23 Total 100 208 84 7 Big Pine Key Federal 88 686 278 no. Private 12 94 38 Total 100 780 316 8 Big Munson Island Private 100 28 11 yes. Total 100 28 11 9 Boca Grande Key Federal 100 62 25 yes. Total 100 62 25 Total All Units Federal 70 7,718 3,123 State 23 2,547 1,031 Private and Other 6 703 284 All 10,968 4,439 Note: Area sizes may not sum due to rounding. We present brief descriptions of all units, and reasons why they meet the definition of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata, below.

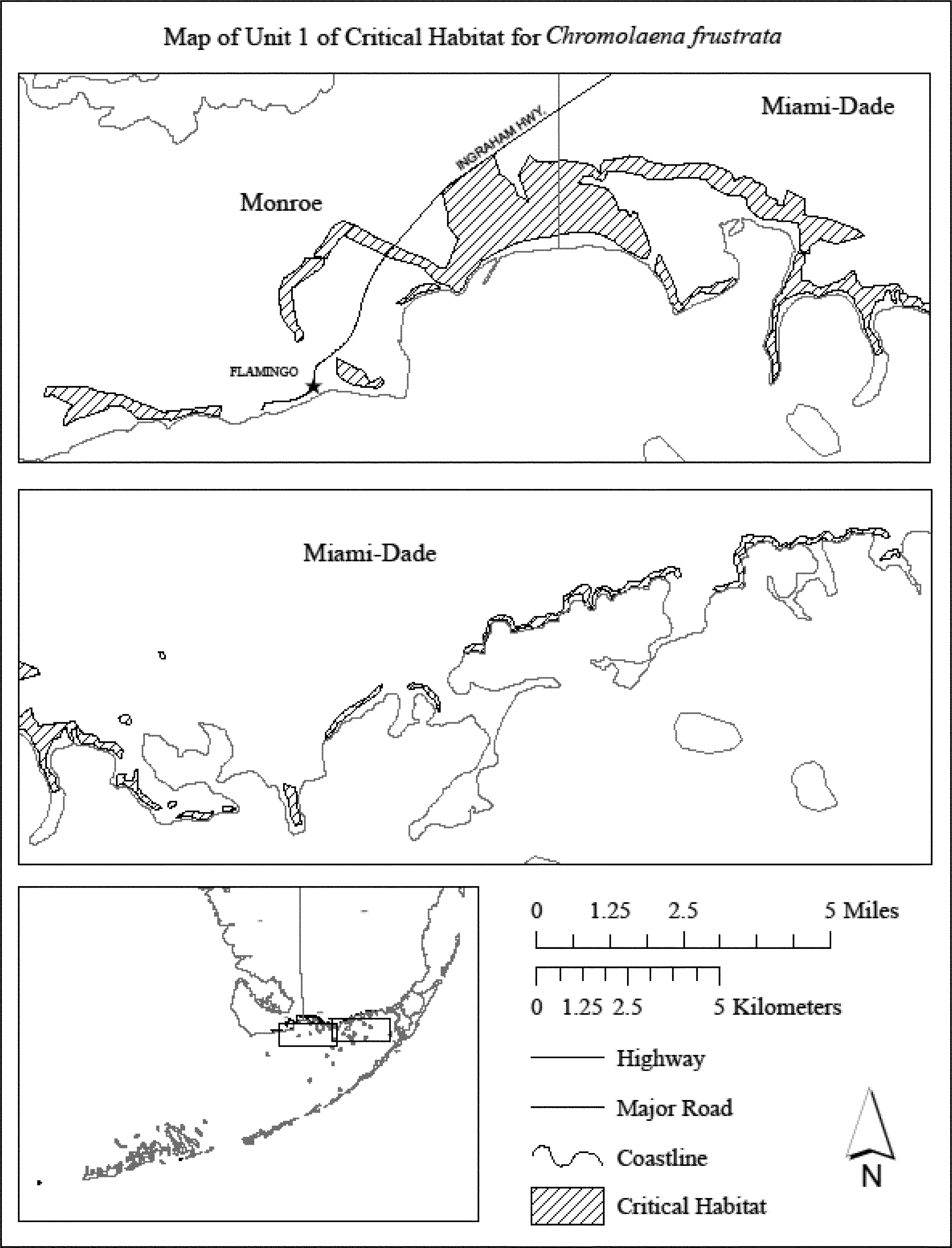

Unit 1: Everglades National Park, Monroe County and Miami-Dade County

Unit 1 consists of a total of 6,166 ac (2,495 ha) in Monroe and Miami-Dade Counties. This unit is composed entirely of lands in Federal ownership, 100 percent of which are located within the Everglades National Park along the southern coast of Florida from Cape Sable to Trout Cove, located between the mean high water line to approximately 2.5 mi (4.02 km) inland. This unit is currently occupied and contains all the physical or biological features required by the species. The unit contains coastal hardwood hammock and buttonwood forest primary constituent elements. The physical or biological features in this unit may require special management considerations or protection to address threats of nonnative plant species and sea-level rise. The National Park Service conducts nonnative species control and monitors Chromolaena frustrata occurrences in ENP.

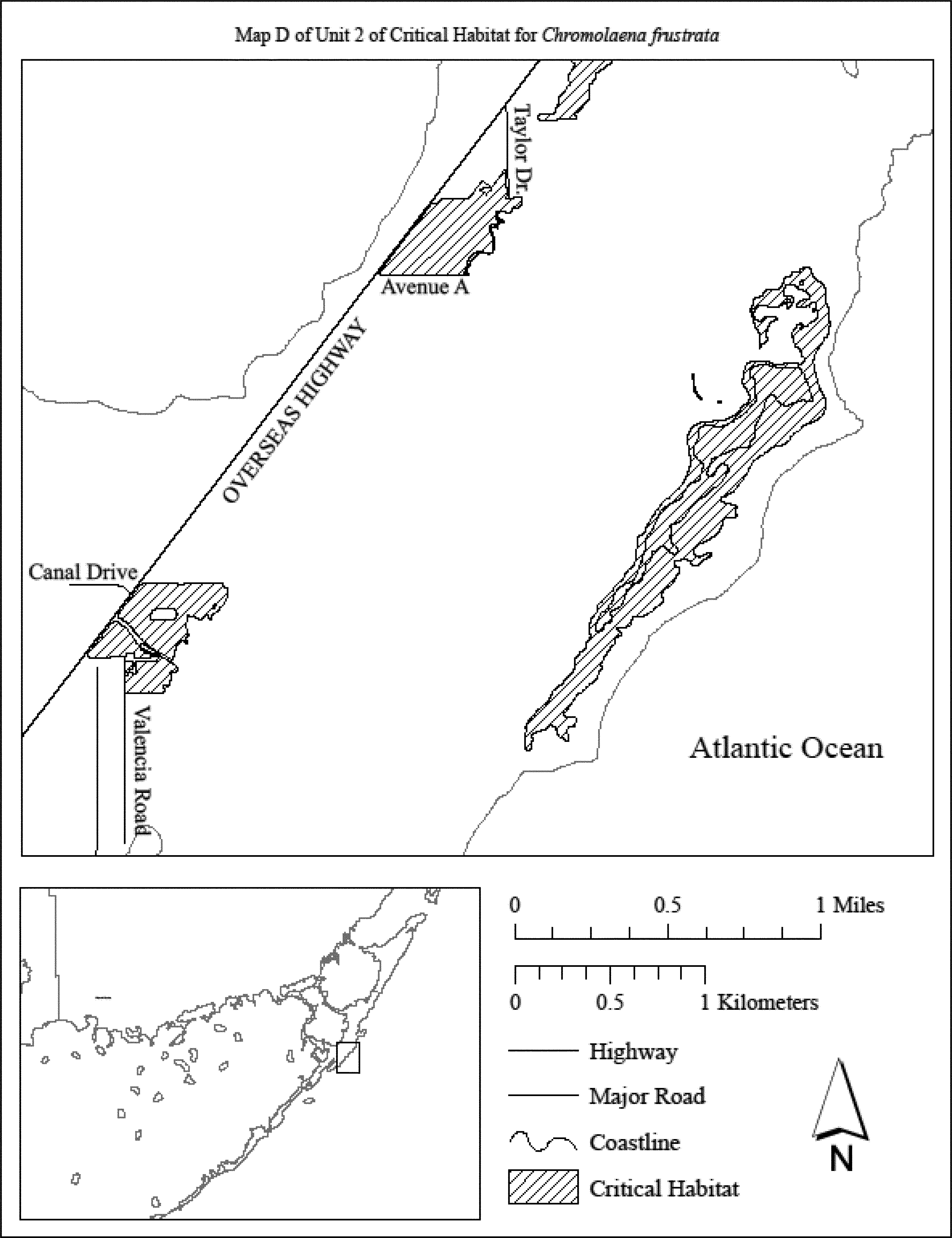

Unit 2: Key Largo, Monroe County

Unit 2 consists of a total of 3,431 ac (1,388 ha) in Monroe County. This unit is composed of Federal lands within Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) (804 ac (325 ha)); State lands within Dagny Johnson Botanical State Park, John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, and the Florida Keys Wildlife and Environmental Area (2,170 ac (878 ha)); and parcels in private ownership (457 ac (185 ha)).

This unit extends from near the northern tip of Key Largo, along the length of Key Largo, beginning at the south shore of Ocean Reef Harbor near South Marina Drive and the intersection of County Road (CR) 905 and Clubhouse Road on the west side of CR 905, and between CR 905 and Old State Road 905, then extending to the shoreline south of South Harbor Drive. The unit then continues on both sides of CR 905 through the Crocodile Lake NWR, Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park, and John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park. The unit then terminates near the junction of U.S. 1 and CR 905 and Garden Cove Drive. The unit resumes on the east side of U.S. 1 from South Andros Road to Key Largo Elementary School; then from intersection of Taylor Drive and Pamela Start Printed Page 1561Street to Avenue A; then from Sound Drive to the intersection of Old Road and Valencia Road; then resumes on the east side of U.S. 1 from Hibiscus Lane and Ocean Drive. The unit continues south near the Port Largo Airport from Poisonwood Road to Bo Peep Boulevard. The unit resumes on the west side of U.S. 1 from the intersection of South Drive and Meridian Avenue to Casa Court Drive. The unit then continues on the west side of U.S. 1 from the point on the coast directly west of Peace Avenue south to Caribbean Avenue. The unit also includes a portion of El Radabob Key.

This unit is not currently occupied but is essential for the conservation of the species because it serves to protect habitat needed to recover the species, reestablish wild populations within the historical range of the species, and maintain populations throughout the historical distribution of the species in the Florida Keys. It also provides area for recovery in the case of stochastic events that otherwise would eliminate the species from the one or more locations it is presently found. The Service conducts nonnative species control efforts at Crocodile Lake NWR, and FDACS conducts nonnative species control efforts at Dagny Johnson Botanical State Park, John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, and the Florida Keys Wildlife and Environmental Area.

Unit 3: Upper Matecumbe Key, Monroe County

Unit 3 consists of a total of 69 ac (28 ha) in Monroe County. This unit is composed of State lands within Lignumvitae Key State Botanical Park, Indian Key Historical State Park (24 ac (10 ha)); City of Islamorada lands within the Key Tree Cactus Preserve and Green Turtle Hammock Park and parcels in private ownership (45 ac (18 ha)).

This unit extends from Matecumbe Avenue south to Seashore Avenue along either side of U.S. 1. The unit then continues along the west side of U.S. 1, including the Green Turtle Hammock Park and a nature preserve owned by the City of Islamorada; straddles U.S. 1 in the vicinity of Indian Key Historical Park; and continues for 0.5 mi (0.8 km) to near the southern tip of Key Largo on the west side of U.S. 1. This unit is currently occupied and contains all the physical or biological features essential for the conservation of the species. It contains the primary constituent elements of coastal berm, coastal rock barren, and rockland hammock.

The physical or biological features in this unit may require special management considerations or protection to address threats of small population size, nonnative species, and sea-level rise. FDACS conducts nonnative species control efforts in Lignumvitae Key State Botanical Park and Indian Key Historical State Park.

Unit 4: Lignumvitae Key, Monroe County

Unit 4 consists of a total of 180 ac (73 ha) in Monroe County. This unit is composed entirely of lands in State ownership, 100 percent of which are located within the Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park (LKBSP) on Lignumvitae Key in the Florida Keys. This unit includes the entire upland area of Lignumvitae Key.

This unit is currently occupied and contains all the physical or biological features essential for the conservation of the species. This unit includes all the primary constituent of rockland hammock and buttonwood forest habitat that occur within LKBSP on Lignumvitae Key. The physical or biological features in this unit may require special management considerations or protection to address threats of small population size, nonnative species, and sea-level rise. FDACS conducts nonnative species control efforts at LKBSP.

Unit 5: Lower Matecumbe Key, Monroe County

Unit 5 consists of a total of 44 ac (18 ha) in Monroe County. The unit is composed of State lands within Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park and parcels owned by the Florida Department of Transportation (22 ac (9 ha)); and parcels in private ownership (22 ac (9 ha)). This unit extends from the east side of U.S. 1 from 0.14 mi (0.2 km) from the north edge of Lower Matecumbe Key, situated across U.S. 1 from Davis Lane and Tiki Lane. The unit continues on either side of U.S. 1 approximately 0.4 mi (0.6 km) from the north edge of Lower Matecumbe Key for approximately 0.6 mi (0.9 km).

This unit is currently occupied and contains all the physical or biological features essential for the conservation of the species. The physical or biological features in this unit may require special management considerations or protection to address threats of small population size, nonnative species, and sea-level rise. FDACS conducts nonnative species control efforts at Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park.

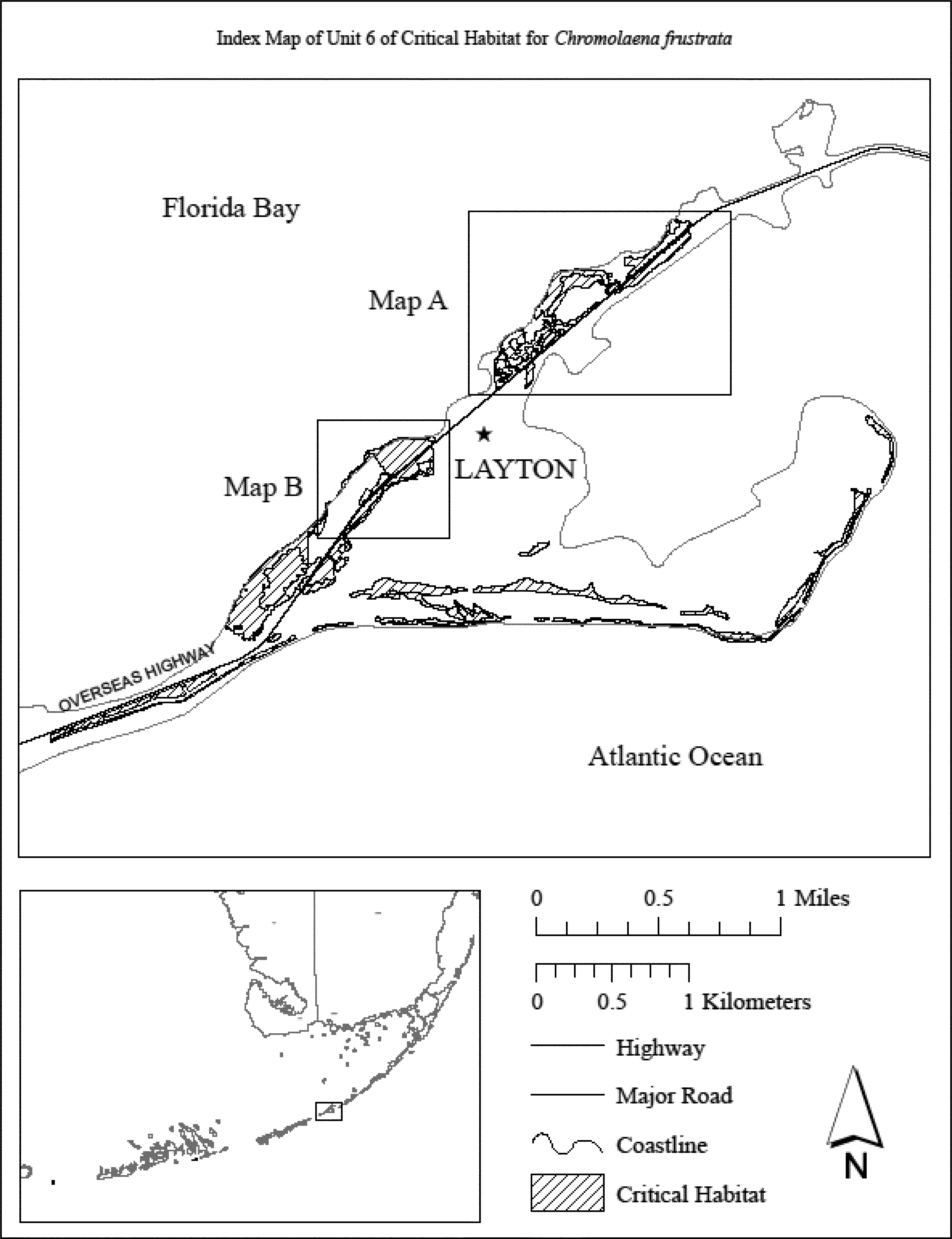

Unit 6: Long Key, Monroe County

Unit 6 consists of a total of 208 ac (84 ha) in Monroe County. This unit is composed of State lands within Long Key State Park (151 ac (61 ha)) and parcels in private ownership (57 ac (23 ha)). The unit extends from the southwestern tip of Long Key along the island's west and south shores.

The unit is currently occupied and contains all the physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species. It contains the PCEs of coastal berm, coastal rock barren, rockland hammock, and buttonwood forest. The physical or biological features in this unit may require special management considerations or protection to address threats of development, small population size, nonnative species, and sea-level rise. FDACS conducts nonnative species control efforts at Long Key State Park.

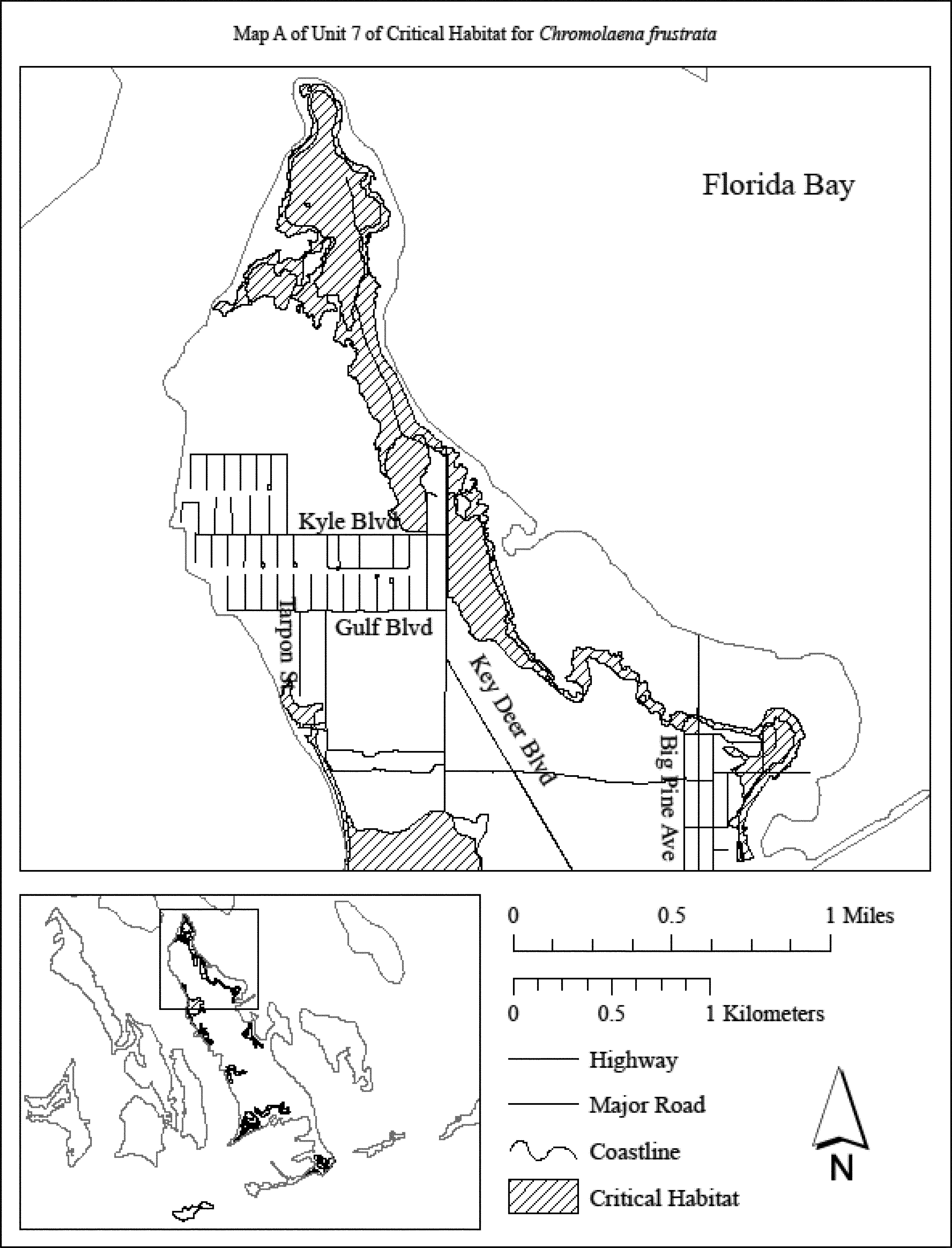

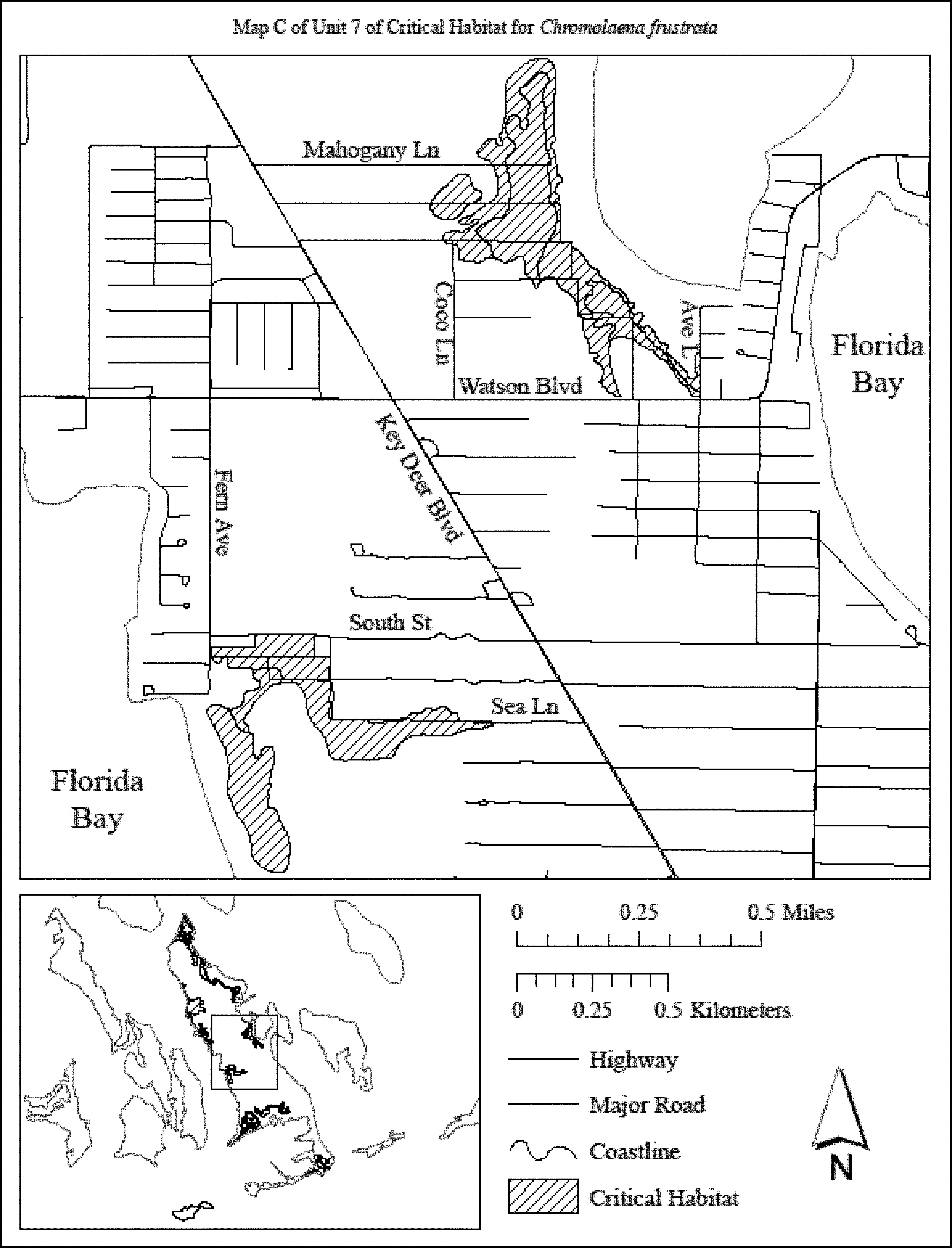

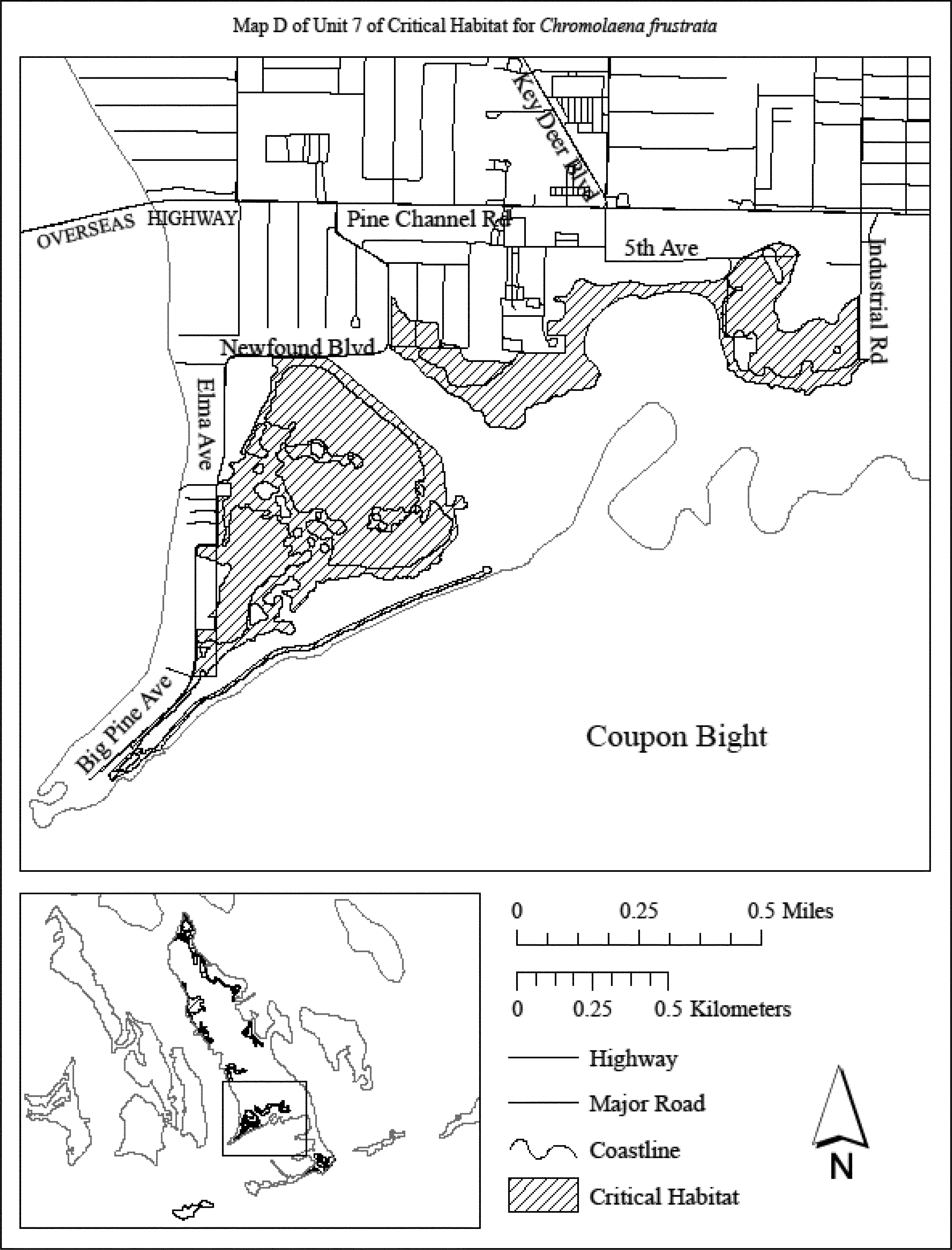

Unit 7: Big Pine Key, Monroe County

Unit 7 consists of a total of 780 ac (316 ha) in Monroe County. This unit is composed of Federal land within the National Key Deer Refuge (NKDR) (686 ac (278 ha)) and parcels in private ownership (94 ac (38 ha)). This unit extends from near the northern tip of Big Pine Key along the eastern shore to the vicinity of Hellenga Drive and Watson Road; from Gulf Boulevard south to West Shore Drive; extending from the southwest tip of Big Pine Key, bordered by Big Pine Avenue and Elma Avenues on the east, Coral and Yacht Club Road, and U.S. 1 on the north, and Industrial Avenue on the east; along Long Beach Drive; and from the southeastern tip of Big Pine Key to Avenue A.

This unit is not currently occupied but is essential for the conservation of the species because it serves to protect habitat needed to recover the species, reestablish wild populations within the historical range of the species, and maintain populations throughout the historical distribution of the species in the Florida Keys. It also provides area for recovery in the case of stochastic events that otherwise hold the potential to eliminate the species from the one or more locations where it is presently found. The Service conducts nonnative species control at the National Key Deer Refuge.

Unit 8: Big Munson Island, Monroe County

Unit 8 consists of a total of 28 ac (11 ha) in Monroe County. This unit is composed entirely of lands in private ownership, owned by the Boy Scouts of America. This unit is occupied and contains all the physical or biological features essential for the conservation of the species. It includes all the PCEs of coastal berm, rockland hammock, and buttonwood forest habitat that occur on Big Munson Island.Start Printed Page 1562

The physical or biological features in this unit may require special management considerations or protection to address threats of development, recreation, nonnative species, and sea-level rise. No conservation actions are known.

Unit 9: Boca Grande Key, Monroe County

Unit 9 consists of a total of 62 ac (25 ha) in Monroe County. This unit is composed entirely of lands in Federal ownership, 100 percent of which is located within the Key West National Wildlife Refuge. This unit is occupied and contains all the physical or biological features essential for the conservation of the species. This unit includes all the primary constituent elements of coastal berm, rockland hammock, and buttonwood forest habitat on the island, comprising the entirety of Boca Grande Key.

The physical or biological features in this unit may require special management considerations or protection to address threats of small population size, nonnative species, and sea-level rise. The Service conducts nonnative species control at the Key West Refuge.

Unit 9 of the critical habitat units for Chromolaena frustrata is currently designated as critical habitat under the Act for the wintering piping plover (Charadrius melodus, 50 CFR 17.95(b)), and Units 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are designated for the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus, 50 CFR 17.95(c)).

Effects of Critical Habitat Designation

Section 7 Consultation

Section 7(a)(2) of the Act requires Federal agencies, including the Service, to ensure that any action they fund, authorize, or carry out is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered species or threatened species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitat of such species. In addition, section 7(a)(4) of the Act requires Federal agencies to confer with the Service on any agency action which is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any species proposed to be listed under the Act or result in the destruction or adverse modification of proposed critical habitat.

Decisions by the 5th and 9th Circuit Courts of Appeals have invalidated our regulatory definition of “destruction or adverse modification” (50 CFR 402.02) (see Gifford Pinchot Task Force v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 378 F. 3d 1059 (9th Cir. 2004) and Sierra Club v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service et al., 245 F.3d 434 (5th Cir. 2001)), and we do not rely on this regulatory definition when analyzing whether an action is likely to destroy or adversely modify critical habitat. Under the provisions of the Act, we determine destruction or adverse modification on the basis of whether, with implementation of the proposed Federal action, the affected critical habitat would continue to serve its intended conservation role for the species.

If a Federal action may affect a listed species or its critical habitat, the responsible Federal agency (action agency) must enter into consultation with us. Examples of actions that are subject to the section 7 consultation process are actions on State, tribal, local, or private lands that require a Federal permit (such as a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers under section 404 of the Clean Water Act (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.) or a permit from the Service under section 10 of the Act) or that involve some other Federal action (such as funding from the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Aviation Administration, or the Federal Emergency Management Agency). Federal actions not affecting listed species or critical habitat, and actions on State, tribal, local, or private lands that are not federally funded or authorized, do not require section 7 consultation.

As a result of section 7 consultation, we document compliance with the requirements of section 7(a)(2) through our issuance of:

(1) A concurrence letter for Federal actions that may affect, but are not likely to adversely affect, listed species or critical habitat; or

(2) A biological opinion for Federal actions that may affect and are likely to adversely affect, listed species or critical habitat.

When we issue a biological opinion concluding that a project is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of a listed species and/or destroy or adversely modify critical habitat, we provide reasonable and prudent alternatives to the project, if any are identifiable, that would avoid the likelihood of jeopardy and/or destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat. We define “reasonable and prudent alternatives” (at 50 CFR 402.02) as alternative actions identified during consultation that:

(1) Can be implemented in a manner consistent with the intended purpose of the action,

(2) Can be implemented consistent with the scope of the Federal agency's legal authority and jurisdiction,

(3) Are economically and technologically feasible, and

(4) Would, in the Director's opinion, avoid the likelihood of jeopardizing the continued existence of the listed species and/or avoid the likelihood of destroying or adversely modifying critical habitat.

Reasonable and prudent alternatives can vary from slight project modifications to extensive redesign or relocation of the project. Costs associated with implementing a reasonable and prudent alternative are similarly variable.

Regulations at 50 CFR 402.16 require Federal agencies to reinitiate consultation on previously reviewed actions in instances where we have listed a new species or subsequently designated critical habitat that may be affected and the Federal agency has retained discretionary involvement or control over the action (or the agency's discretionary involvement or control is authorized by law). Consequently, Federal agencies sometimes may need to request reinitiation of consultation with us on actions for which formal consultation has been completed, if those actions with discretionary involvement or control may affect subsequently listed species or designated critical habitat.

Application of the “Adverse Modification” Standard

The key factor related to the adverse modification determination is whether, with implementation of the proposed Federal action, the affected critical habitat would continue to serve its intended conservation role for the species. Activities that may destroy or adversely modify critical habitat are those that alter the physical or biological features to an extent that appreciably reduces the conservation value of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata. As discussed above, the role of critical habitat is to support life-history needs of the species and provide for the conservation of the species.

Section 4(b)(8) of the Act requires us to briefly evaluate and describe, in any proposed or final regulation that designates critical habitat, activities involving a Federal action that may destroy or adversely modify such habitat, or that may be affected by such designation.

Activities that may affect critical habitat, when carried out, funded, or authorized by a Federal agency, should result in consultation for Chromolaena frustrata. These activities include, but are not limited to:

(1) Actions that would significantly alter the hydrology or substrate, such as Start Printed Page 1563ditching or filling. Such activities may include, but are not limited to, road construction or maintenance, and residential, commercial, or recreational development.

(2) Actions that would significantly alter vegetation structure or composition, such as clearing vegetation for construction of residences, facilities, trails, and roads.

(3) Actions that would introduce nonnative species that would significantly alter vegetation structure or composition. Such activities may include, but are not limited to, residential and commercial development, and road construction.

Exemptions

Application of Section 4(a)(3) of the Act

Section 4(a)(3)(B)(i) of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533(a)(3)(B)(i)) provides that: “The Secretary shall not designate as critical habitat any lands or other geographic areas owned or controlled by the Department of Defense, or designated for its use, that are subject to an integrated natural resources management plan (INRMP) prepared under section 101 of the Sikes Act (16 U.S.C. 670a), if the Secretary determines in writing that such plan provides a benefit to the species for which critical habitat is proposed for designation.” There are no Department of Defense lands with a completed INRMP within the proposed critical habitat designation. Therefore, we are not exempting any lands from this final designation of critical habitat for Chromolaena frustrata pursuant to section 4(a)(3)(B)(i) of the Act.

Exclusions

Application of Section 4(b)(2) of the Act

Section 4(b)(2) of the Act states that the Secretary shall designate and make revisions to critical habitat on the basis of the best available scientific data after taking into consideration the economic impact, national security impact, and any other relevant impact of specifying any particular area as critical habitat. The Secretary may exclude an area from critical habitat if she determines that the benefits of such exclusion outweigh the benefits of specifying such area as part of the critical habitat, unless she determines, based on the best scientific data available, that the failure to designate such area as critical habitat will result in the extinction of the species. In making that determination, the statute on its face, as well as the legislative history, is clear that the Secretary has broad discretion regarding which factor(s) to use and how much weight to give to any factor.