2013-25397. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for Vandenberg Monkeyflower

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 64840

AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Proposed rule.

SUMMARY:

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, propose to list Vandenberg monkeyflower as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act. If we finalize this rule as proposed, it would extend the Endangered Species Act's protections to this plant. The effect of this regulation will be to add Vandenberg monkeyflower to the List of Endangered and Threatened Plants under the Endangered Species Act.

DATES:

We will accept all comments received or postmarked on or before December 30, 2013. Comments submitted electronically using the Federal eRulemaking Portal (see ADDRESSES section below) must be received by 11:59 p.m. Eastern Time on the closing date. We must receive requests for public hearings, in writing, at the address shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT by December 13, 2013.

ADDRESSES:

You may submit comments by one of the following methods:

(1) Electronically: Go to the Federal eRulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov and search for FWS-R8-ES-2013-0078, which is the docket number for this rulemaking. Then, in the Search panel on the left side of the screen, under the Document Type heading, click on the Proposed Rules link to locate this document. You may submit a comment by clicking on “Comment Now!”

(2) By hard copy: Submit by U.S. mail or hand-delivery to: Public Comments Processing, Attn: FWS-R8-ES-2013-0078; Division of Policy and Directives Management; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, MS 2042-PDM; Arlington, VA 22203.

We request that you send comments only by the methods described above. We will post all information received on http://www.regulations.gov. This generally means that we will post any personal information you provide us (see the Information Requested section below for more information).

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Stephen P. Henry, Acting Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office, 2493 Portola Road, Suite B, Ventura, CA 93003; telephone 805-644-1766; facsimile 805-644-3958. If you use a telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD), call the Federal Information Relay Service (FIRS) at 800-877-8339.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. Under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531, et seq.) (Act), if a species is determined to be an endangered or threatened species throughout all or a significant portion of its range, we are required to promptly publish a proposal in the Federal Register and make a determination on our proposal within 1 year. Critical habitat shall be designated, to the maximum extent prudent and determinable, for any species determined to be an endangered or threatened species under the Act. Listing a species as an endangered or threatened species and designations and revisions of critical habitat can only be completed by issuing a rule.

This rule consists of a proposed rule to list Vandenberg monkeyflower (previously identified as a candidate for listing by the name Mimulus fremontii var. vandenbergensis, currently known as Diplacus vandenbergensis, and hereafter referred to as Vandenberg monkeyflower, with the exception of the Description and Taxonomy section below) as an endangered species. This plant occurs in nine locations exclusively on Burton Mesa, a distinct geographic region in Santa Barbara County, California.

The basis for our action. Under the Act, we can determine that a species is an endangered or threatened species based on any of five factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) Disease or predation; (D) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

We have determined Vandenberg monkeyflower faces threats under Factors A, D, and E. The greatest threat to Vandenberg monkeyflower is the presence and expansion of invasive, nonnative plants that are abundant on Burton Mesa, particularly occurring within or adjacent to all known occurrences of Vandenberg monkeyflower. Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat includes sandy openings (canopy gaps) within the dominant vegetation. Ground-disturbing activities (including wildfires) create additional open areas that are invaded by nonnative plants, which precludes establishment of Vandenberg monkeyflower. Furthermore, the availability of habitat for Vandenberg monkeyflower and its small overall population size may be affected by a suite of threats (including stochastic events such as wildfire and a changing climate) acting synergistically on the species. Based on the best available scientific and commercial information, we find that the species has a restricted range, faces ongoing and future threats across its range, and is in danger of extinction throughout all of its range.

We will seek peer review. We are seeking comments from knowledgeable individuals with scientific expertise to review our analysis of the best available science and application of that science and to provide any additional scientific information to improve this proposed rule. Because we will consider all comments and information received during the comment period, our final determination may differ from this proposal.

Information Requested

We intend that any final action resulting from this proposed rule will be based on the best scientific and commercial data available and be as accurate and as effective as possible. Therefore, we request comments or information from the public, other concerned governmental agencies, Native American tribes, the scientific community, industry, or any other interested parties concerning this proposed rule. We particularly seek comments concerning:

(1) The species' biology, range, and population trends, including:

(a) Habitat requirements for establishment, growth, and reproduction;

(b) Genetics and taxonomy;

(c) Historical and current range including distribution patterns;

(d) Historical and current population levels, and current and projected trends; and

(e) Past and ongoing conservation measures for the species, its habitat, or both.

(2) The factors that are the basis for making a listing determination for a species under section 4(a) of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533(a)), which are:Start Printed Page 64841

(a) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range;

(b) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

(c) Disease or predation;

(d) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or

(e) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

(3) Biological, commercial trade, or other relevant data concerning any threats (or lack thereof) to Vandenberg monkeyflower and regulations that may be addressing those threats.

(4) Additional information concerning the historical and current status, range, distribution, and population size of Vandenberg monkeyflower, including the locations of any additional occurrences of this species.

(5) Current or planned activities in the areas occupied by Vandenberg monkeyflower and possible impacts of these activities on this species and its habitat.

(6) Information on the projected and reasonably likely impacts of climate change on Vandenberg monkeyflower and its habitat.

(7) Information related to our interpretation and analysis of the best scientific and commercial data and our proposed status determination for the species.

Please include sufficient information with your submission (such as scientific journal articles or other publications) to allow us to verify any scientific or commercial information you include.

Please note that submissions merely stating support for or opposition to the action under consideration without providing supporting information may not meet the standard of information required by section 4(b)(1)(A) of the Act, which requires that determinations as to whether any species is an endangered or threatened species must be made “solely on the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available.”

You may submit your comments and materials concerning this proposed rule by one of the methods listed in ADDRESSES. We request that you send comments only by the methods described in ADDRESSES.

If you submit information via http://www.regulations.gov,, your entire submission—including any personal identifying information—will be posted on the Web site. If your submission is made via a hardcopy that includes personal identifying information, you may request at the top of your document that we withhold this information from public review. However, we cannot guarantee that we will be able to do so. We will post all hardcopy submissions on http://www.regulations.gov. Please include sufficient information with your comments to allow us to verify any scientific or commercial information you include.

Comments and materials we receive, as well as supporting documentation we used in preparing this proposed rule, will be available for public inspection at http://www.regulations.gov,, or by appointment during normal business hours at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ventura Field Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT).

Previous Federal Actions

We first identified Vandenberg monkeyflower as a candidate species in a notice of review published in the Federal Register on November 10, 2010 (75 FR 69222). Vandenberg monkeyflower was given a listing priority number of 3, which denotes a subspecies [or variety] facing an imminent threat of high magnitude. Notices of review reconfirming its candidate status were also published in the Federal Register on October 26, 2011 (76 FR 66370), and November 21, 2012 (77 FR 69994). Candidate taxa are plants and animals for which the Service has sufficient information on their biological status and threats to propose them as endangered or threatened under the Act, but for which development of a proposed listing regulation is precluded by other higher priority listing activities. We may identify a taxon as a candidate for listing after we conduct an evaluation of its status on our own initiative, or after we make a positive finding on a petition to list a species. No petitions seeking the listing of Vandenberg monkeyflower have been submitted nor have other Federal reviews been conducted for Vandenberg monkeyflower.

On May 10, 2011, we filed a multiyear work plan as part of a proposed settlement agreement with Wild Earth Guardians and others in a consolidated case in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. On September 9, 2011, the court accepted our agreement with plaintiffs in Endangered Species Act Section 4 Deadline Litig., Misc. Action No. 10-377 (EGS), MDL Docket No. 2165 (D. DC) (known as the “MDL case”) on a schedule to publish proposed rules or not-warranted findings for the 251 species designated as candidates in 2010 no later than September 30, 2016. We are submitting this proposed rule in compliance with the MDL settlement agreement.

Elsewhere in today's Federal Register, we propose to designate critical habitat for Vandenberg monkeyflower under the Act.

Status Assessment for Vandenberg Monkeyflower

Background

It is our intent to discuss below only those topics directly relevant to the listing of Vandenberg monkeyflower as endangered in this section of the proposed rule.

Description and Taxonomy

Vandenberg monkeyflower is a small, annual herbaceous plant that grows from 0.5 to 10 inches (in) (1.2 to 25.4 centimeters (cm)) tall. The stems are glandular and usually green with purplish tinting. Leaves are obovate (narrowly elliptic) and reach 1.2 in (3 cm) in length. Plants produce a single flower or plants are branched producing multiple flowers. The tubular yellow flowers are bilaterally symmetrical, with the distal ends of the petals forming a unique structure that is likened to a face; hence the common name monkeyflower. Seed capsules are ovoid and reach 0.5 in (1.3 cm) in length. The capsule splits open longitudinally from the tip to release approximately 20 to 100 seeds.

Vandenberg monkeyflower was first described as Mimulus fremontii (Benth.) A. Gray var. vandenbergensis D.M. Thompson (Thompson 2005, p. 134) as a member of the Scrophulariaceae (figwort family). This is the name and family placement we have previously followed. Molecular systematics studies examining members of the Scrophulariaceae, including Mimulus, determined that this genus and a few others constituted a separate monophyletic group warranting recognition at the family rank as Phrymaceae (Beardsley and Olmstead 2002, pp. 1193-1101; Olmstead 2002, p. 18). Placement of Mimulus in the family Phrymaceae is recognized by species experts, is used in the recent flora of California (Thompson 2012, pp. 988-998), and will be treated as such in the upcoming volume of the Flora of North America.

In 2012, Barker et al. (2012) recognized a redefined genus Diplacus that includes 46 taxa previously segregated as Mimulus, including Vandenberg monkeyflower as Diplacus vandenbergensis (D.M. Thompson) Nesom (Barker et al. 2012, p. 29). The citation in Barker et al. (2012, p. 29) attributes the nomenclatural combination at the species rank to Nesom in Phytoneuron 2012-47: 2, which was published electronically on the same day as Barker et al. (2012). The Start Printed Page 64842current citation for Vandenberg monkeyflower is at the species rank as Diplacus vandenbergensis (D.M. Thompson) G.L. Nesom. This combination is accepted by species and genus experts and will be used in the upcoming treatment in the Flora of North America. Accordingly, we will use the correct name (Diplacus vandenbergensis) and family attribution (Phrymaceae) throughout this and subsequent documents.

Life History

The life history of Vandenberg monkeyflower has not been thoroughly studied, but certain characteristics appear similar to other small annual herbs. Vandenberg monkeyflower is shallow-rooted (Thompson 2005, p.131; Consortium of California Herbaria (Consortium 2010)) and has seeds that germinate during winter rains, typically between November and February (Thompson 2005, p. 23), which is similar to other small annual species that grow in sandy openings in chaparral and are adapted to the Mediterranean climate zone of California. For instance, Lessingia glandulifera (lessingia) is an annual herb that grows in sandy openings in chaparral, is shallow-rooted, and is commonly associated with Vandenberg monkeyflower (Davis and Mooney 1985, p. 528). Rooting depth is positively related to above-ground size, with annuals having the smallest above-ground size and rooting depth in the soil (Schenk and Jackson 2002, pp. 484-485).

Vandenberg monkeyflower is sensitive to annual levels of rainfall (Thompson 2005, p. 23), and, therefore, germination of resident seed banks may be low or nonexistent in unfavorable years, with little or no visible aboveground expression of the species. Many annual monkeyflower species, including Vandenberg monkeyflower, need early rainfall along with continued rains in late winter or early spring for a substantial number of seeds to germinate, and do not respond well when only later rainfall is available (Thompson 2005, p. 23; Fraga in litt. 2012). Vandenberg monkeyflower flowers mostly from late March through June with fruits maturing from late April through July (Thompson 2005, p. 130).

Seed banks develop when a plant produces more viable seeds than germinate in any given year. Seed banks contribute to the long-term persistence of a species by sustaining them through periods when conditions are not conducive to adequately germinate, reproduce, and replenish the seed bank (such as when there is not sufficient rainfall for plants to germinate, grow, and produce enough seeds to maintain the population at the same size from year to year) (Rees and Long 1992, entire; Adams et al. 2005, pp. 432-434; Satterthwaite et al. 2007, entire). The annual differences in the numbers and location of aboveground plants indicate the presence of a seed bank.

The reproductive biology of Vandenberg monkeyflower has not been specifically studied; however, it is likely similar to closely related Diplacus species that occur in similar habitats. In general, annual species of Diplacus are self-compatible (able to be fertilized by its own pollen) but are also visited by a wide array of pollinators, which results in a mixed mating system that utilizes both self-fertilization and cross-fertilization (Sutherland and Vickery 1988, p. 334; Leclerc-Potvin and Ritland 1994, pp. 201-204; Fraga in litt. 2012). The large size of the flower relative to the size of the plant suggests that Vandenberg monkeyflower is allocating significant resources into attracting pollinators; therefore, this species is thought to typically breed through outcrossing, and is dependent on pollinators to achieve seed production (Fraga in litt. 2012).

Species of Diplacus are predominantly bee-pollinated, although the genus also includes species that are pollinated by hummingbirds, hawk moths (Sphingidae), beeflies (Bombyliidae), and other flies (order Diptera) (Wu et al. 2008, p. 224). Species of bees that have been observed to visit flowers of Vandenberg monkeyflower include sweat bees (Dufourea versatilis rubriventris), miner bees (Perdita nitens, Caliopsis [Nomadopsis] fracta and C. Nomadopsis trifolii), mason bees (Hoplitis product bernardina), and leaf-cutter bees (Anthidium collectum, Chelostoma cockerelli, C. minutum, C. phaceliae, Chelostomopsis rubifloris, and Ashmeadiella timberlakei timberlakei) (Krombein et al. 1979, pp. 1863-2030; Bugguide 2012; The Xerces Society 2012). Additionally, Inouye (in litt. 2012) observed that small solitary bees were the most common pollinators on three other species of small annual monkeyflower species from dry and mesic habitats (D. androsaceus, D. angustatus, and D. douglasii); and Fraga (in litt. 2012) has observed halictid bees (Halictidae) on other small monkeyflower species.

Seeds of Vandenberg monkeyflower are small and light in weight, dispersing primarily by gravity and also by water and wind over relatively short distances (Thompson 2005, p. 130; Fraga in litt. 2012). The small size of the seed makes it likely that short-distance dispersal could also be facilitated by ants, as has been noted for other small-seeded plant taxa (Cain et al. 1998, pp. 328-330). Given that the Burton Mesa area is subject to occasional high winds (see discussion in Climate section below), long-distance dispersal likely occurs during these wind events. Wind dispersal results in a random dispersal of seeds, some of which fall into suitable habitat and some do not.

Geographic Setting

Vandenberg monkeyflower occurs only at low elevations and close to the coast in a distinct region in western Santa Barbara County known as Burton Mesa (Wilken and Wardlaw 2010, p. 2). Burton Mesa is a physiographic region situated between the Purisima Hills to the north and the Santa Ynez River to the south. The topography of Burton Mesa comprises a low, flat-topped series of hills averaging 400 feet (ft) (133 meters (m)) in elevation (Ferren et al. 1984, p. 3; Dibblee 1988). Level upland expanses from 328 to 394 ft (100 to 120 m) above sea level are dissected by streams that have formed wide valleys with short steep slopes (Davis 1987, p. 318). Underlying this region is the Burton Mesa dune sheet, which extends from Shuman Canyon on Vandenberg Air Force Base (AFB) in the north, roughly southeast along the southern slopes of the Purisima Hills and eastward to a point approximately 22 mi (35 km) from the present shoreline in the Santa Ynez River Valley (Cooper 1967, pp. 89-91; Hunt 1993, pp. 8-9).

Climate

Burton Mesa experiences a Mediterranean climate, with mild, moist winters and moderately warm, rainless summers. The region is strongly influenced by the prevailing westerly transoceanic air currents. Late afternoon and early evening are often characterized by onshore breezes or winds during most of the year, but winds are strongest and persistent in late spring and early summer. A marine layer or fog characterizes this coastal region and is heaviest during late spring and early summer mornings. Frost is also a regular occurrence in winter, especially in low-lying areas (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 39).

Habitat

Burton Mesa supports a mosaic of several native vegetation types, including maritime chaparral, maritime chaparral mixed with coastal scrub, oak woodland, and small patches of native grasslands (Wilken and Wardlaw 2010, Start Printed Page 64843p. 2). The maritime chaparral on Burton Mesa is referred to as Burton Mesa chaparral (Odion et al. 1992, pp. 5-6; Sawyer et al. 2009, p. 376), and is dominated by evergreen shrubs and scattered multi-trunked Quercus agrifolia (coast live oak) that form open stands to almost impenetrable thickets over large areas of Burton Mesa, with heights reaching up to 13 ft (4 m) (Gevirtz et al. 2007, pp. 95-96). The dominant endemic species of Burton Mesa chaparral include Ceanothus (Ceanothus impressus var. impressus (Santa Barbara ceanothus) and C. cuneatus var. fascicularis (Lompoc ceanothus)) and Arctostaphylos (Arctostaphylos purissima (Purisima manzanita) and A. rudis (shagbark manzanita)), along with the more widespread Adenostoma fasciculatum (chamise), Heteromeles arbutifolia (toyon), Cercocarpus betuloides (birchleaf mountain mahogany), Salvia mellifera (black sage), and Rhamnus californica (California coffeeberry).

Coast live oak is an important dominant in many places on Burton Mesa, attaining 40 to 70 percent crown cover in older undisturbed patches of habitat. Ericameria ericoides (mock heather), with its wind-dispersed seeds, is most often observed at trail edges in dense chaparral, but appears in greater numbers in large open areas and coastal scrub (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 96). Annual grassland and coastal sage scrub characterized by mock heather, Artemisia californica (California sagebrush), and Baccharis pilularis (coyote brush) occur on formerly cleared sites and on xeric (dry) slopes. Some poorly drained upland sites in the central and western portions of Burton Mesa form seasonal wetlands characterized by native perennial grasses such as Elymus glaucus (blue wildrye) and vernal pool species including Eryngium armatum (coastal button-celery) (Davis et al. 1988, p. 172). The vegetation transitions to coastal sage scrub habitat as it nears the ocean and into other terrestrial habitats east of Purisima Canyon on the eastern side of La Purisima Mission State Historic Park (SHP) (Gevirtz et al. 2005, p. 86). The edaphic (soil) variable with the greatest effect on vegetation composition is the depth of soil overlying the bedrock or subsoil pan (Davis et al. 1988, p. 188). Soils on Burton Mesa become very shallow toward the north and west, and chaparral shrubs decrease in height and density with decreasing soil depth (Odion et al. 1992, p. 6).

Vandenberg monkeyflower does not grow beneath the canopy of shrubs or oaks, but rather in the sandy openings (canopy gaps) that occur in-between shrubs. Sandy openings have been noted for their high abundance and diversity of annual and perennial herbaceous species, compared to those found in the understory of the shrub canopy (Hickson 1987, Davis et al. 1989; Keeley et al. 1981; Horton and Kraebel 1955). Vandenberg monkeyflower is currently known to occur within sandy openings at nine extant locations; one additional location is potentially extirpated (see Distribution of Vandenberg Monkeyflower below). Because portions of Burton Mesa are inaccessible and difficult to survey, Vandenberg monkeyflower has the potential to occur in areas where it has not yet been observed within sandy openings. However, not all sandy openings within the shrub canopy appear to be currently suitable for Vandenberg monkeyflower because some of the sandy openings consist of sands that structurally seem more consolidated and currently do not support this species (Rutherford in litt. 2012). To date, all of the extant occurrences of Vandenberg monkeyflower are within sandy openings where the structure of the sands appears loose (Rutherford in litt. 2012).

The amount of Vandenberg monkeyflower suitable habitat currently available has changed over time. Prior to 1938, approximately 23,550 ac (9,350 ha) of maritime chaparral was present on Burton Mesa (Hickson 1987, p. 34). For the purposes of this analysis, we determined in 2012 that approximately 10,057 ac (4,070 ha) of maritime chaparral habitat remain on Burton Mesa, which represents a loss of 53 percent of the original upland habitat (Figure 1; Service 2012a, unpublished data). We then estimated the amount of Burton Mesa considered as sandy openings where Vandenberg monkeyflower could potentially occur. Based on inspection of color imagery (National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) 2009) of areas within Burton Mesa where this species occurs, we used the range of image pixel values among 20 point locations to define bare ground while all other pixel values defined vegetated areas. We calculated the total area encompassed by bare ground and vegetation by multiplying the number of bare ground and vegetated pixels by 1 square meter (the ground resolution of a pixel in the NAIP data). Roads, buried pipeline rights-of-way, and building footprints were removed to estimate the percent of Burton Mesa that currently comprise sandy openings.

Start Printed Page 64844Results indicate up to approximately 20 percent of the total area of remaining Burton Mesa chaparral comprises sandy openings, which is a high estimate because this may include areas of bare ground that are not sandy openings suitable for Vandenberg monkeyflower, such as walking trails (Service 2012b, unpublished data). The percentage Start Printed Page 64845would likely change over time depending on whether chaparral stands continue to age and increase in canopy cover, or are burned to temporarily increase the amount of sandy openings. Additionally, the location of sandy openings on Burton Mesa would likely shift over time because individual shrubs continue to mature and increase in cover or die, creating temporary gaps in the shrub canopy.

The structure of Burton Mesa chaparral comprises a mosaic of vegetation patches interspersed with sandy openings that varies from place to place. Within a given substrate, the chaparral composition is a reflection of stand age or shrub canopy cover, disturbance history (whether the area was cleared in the past or nonnative species were planted), history of wildfire, and distance from the coast (Davis et al. 1988, p. 188; Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 97). Although the sandy openings that Vandenberg monkeyflower occupies are only a small percent of the total amount of Burton Mesa chaparral habitat, because the sandy openings and vegetation form a mosaic vegetation community that structurally may vary over time, it is impossible to separate out the sandy openings from the rest of the Burton Mesa chaparral vegetation. Therefore, for the purposes of this rule, we consider suitable Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat to consist of Burton Mesa chaparral, which would include the sandy openings and the dominant vegetation that characterize this vegetation community.

Other low-growing native annual species that often co-occur with Vandenberg monkeyflower in sandy openings include: Mucronea californica (California spineflower); Castillleja exserta (purple owl's clover); Logfia filaginoides (California filago); Lessingia glandulifera (lessingia); Layia glandulosa (white tidy tips); Chaenactis glabriuscula (pincushion); and Plantago erecta (plantain). Frequently co-occurring herbaceous native perennial species include Horkelia cuneata (horkelia) and Croton californicus (croton) (Meyer in litt. 2010a). Nonnative annual and perennial species are also known to occur in Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat. Nonnative annual species include (but are not limited to) Bromus diandrus (ripgut brome) and Hypochaeris glabra (smooth cat's-ear) (Meyer in litt. 2010a). Nonnative perennial species include: Ehrharta calycina (South African perennial veldt grass (veldt grass)), Carpobrotus edulis (iceplant), Brassica tournefortii (Sahara mustard), and Cortaderia jubata (pampas grass).

Land Ownership

The western portion of Burton Mesa is Federal land within Vandenberg AFB (Davis et al. 1988, p. 170). Vandenberg AFB contains approximately 99,000 acres (ac) (40,064 hectares (ha)); approximately 8,114 ac (3,284 ha) is maritime chaparral mixed with coastal sage scrub, veldt grass, pampas grass, herbs, and coast live oak on Burton Mesa within Base boundaries (Air Force 2011c, Appendix A—Figure 5-3; Lum in litt. 2012d). Vandenberg AFB is managed by the U.S. Air Force.

To the east of Vandenberg AFB, the State of California received 5,078 ac (2,055 ha) from Union Oil Company in 1990 as part of a settlement of two antitrust lawsuits (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 2). The land acquired by the State formed the Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve (Reserve) and encompasses most of the maritime chaparral that occurs to the east of Vandenberg AFB (Odion et al. 1992, p. 6). The western boundary of the Reserve abuts the eastern boundary of Vandenberg AFB and is delineated by a 100-ft (30-m) wide fuel break (a gap in vegetation designed to act as a barrier to slow progress of a potential wildfire). Additional lands have since been added to the Reserve since 1990, bringing its total acreage to 5,186 ac (2,099 ha) (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 3). The Reserve contains five management units (Vandenberg, Santa Lucia, Purisima Hills, Encina, and La Purisima) and is situated on the eastern Burton Mesa and foothills of the Purisima Hills (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 7). The Reserve is managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). CDFW was formerly California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG), and because historic documents prior to 2013 use this old name, the abbreviations CDFG and CDFW will both be used interchangeably for references cited throughout the remainder of this document.

Residential communities such as Vandenberg Village, Clubhouse Estates, Mesa Oaks, and Mission Hills fragment (divide into small noncontiguous pieces) the Reserve and other non-Federal lands on Burton Mesa. The southern portion of the mesa and beyond the southern boundary of the Reserve comprises agricultural lands as well as land owned by the Department of Justice (which houses the U.S. Bureau of Prisons Federal Penitentiary Complex at Lompoc (Lompoc Penitentiary)). The jagged northern perimeter of Burton Mesa is adjacent to an active oil field operated by Plains Exploration and Production Company (PXP).

To the east of the Reserve, La Purisima Mission State Historic Park (SHP) contains 980 ac (397 ha) (California State Parks 1991, p. 9) and is separated from the Reserve by the residential communities of Mesa Oaks and Mission Hills. La Purisima Mission SHP also abuts the southern boundary of the La Purisima Management Unit of the Reserve. California State Parks manages La Purisima Mission SHP.

Distribution of Vandenberg Monkeyflower

For the purposes of this rule, we define the following terms to refer to individuals of Vandenberg monkeyflower and where they occur. We use the term “occurrence” (consistent with the definition for “element occurrence” used by the California Natural Diversity Data Base (CNDDB)) to be a grouping of plants (individuals) within 0.25 mi (0.4 km) proximity (CNDDB 2010). There may be one or more discrete groupings of plants (individuals) within a single occurrence. We use the term “location” to refer only to a particular site, area, or region, as in “at that location,” with no relation to an assemblage of plants (e.g., polygon, occurrence, population).

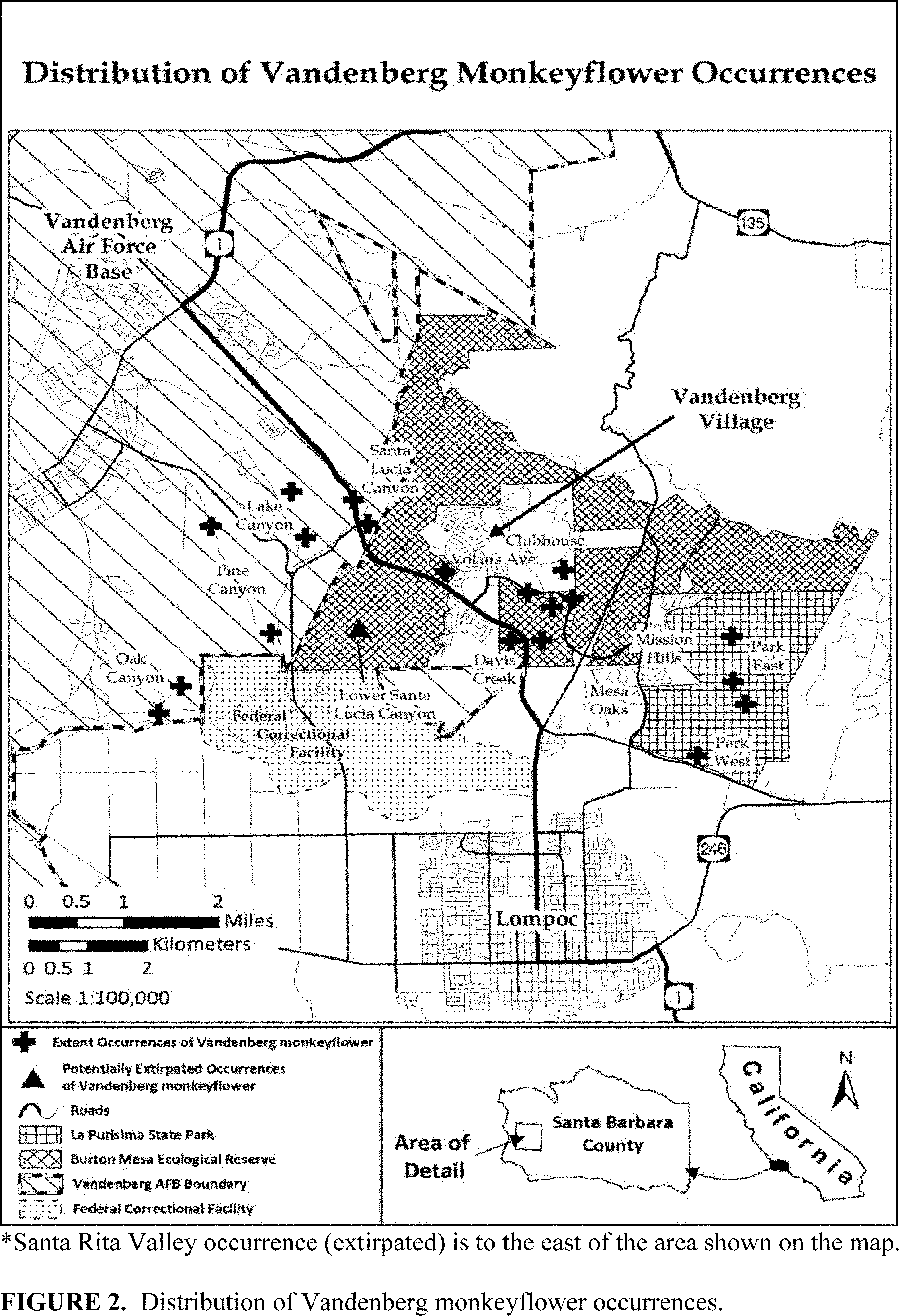

We generally describe the area on Burton Mesa where Vandenberg monkeyflower currently occurs as a crescent-shaped area approximately 7 mi (10.7 km) long by 2 mi (3.0 km) wide. All extant individuals of Vandenberg monkeyflower are located within this area (Consortium) 2010), almost exclusively occurring on thin layers of aeolian- (wind-) deposited sands between approximately 100 and 400 ft (30 to 122 m) in elevation (Wilken and Wardlaw 2010, p. 2). We based the description of suitable habitat on viewing U.S. Geological Survey maps and Google Earth©, and looking at how the occurrences of Vandenberg monkeyflower were spread across the landscape. We did not analyze biological factors such as vegetation or soil type when describing this general area where the species occurs. A discussion of where Vandenberg monkeyflower has been historically observed and where it is currently known to occur follows below. Additionally, Figure 2 includes the known distribution of Vandenberg monkeyflower across its range based on the most recent survey data; Table 1 lists the names of the occurrences, land ownership, and status of each known and historical occurrence.

Start Printed Page 64846Historical Locations

We are aware of historical herbarium collections of Vandenberg monkeyflower from two locations; one of these (Santa Rita Valley) no longer supports habitat for this species (Consortium 2010), and we consider it to be extirpated. The second collection was made from Lower Pine Canyon; although plants have not been relocated at lower Pine Canyon, we consider this collection to be a part of the Pine Canyon occurrence, which is extant. In addition to these two collections, an Start Printed Page 64847historical occurrence of Vandenberg monkeyflower was observed, but not collected, from Lower Santa Lucia Canyon; we consider it to be potentially extirpated. Additional detail on the occurrence of Vandenberg monkeyflower at these three historical locations is provided below.

The first historical collection of Vandenberg monkeyflower was made in 1931 from the Santa Ynez Valley approximately 5 mi (8 km) west of Buellton along State Highway 246 and east of La Purisima (Consortium 2010; Santa Barbara Botanic Garden (SBBG) 2005). This site was surveyed multiple times in 2006 (Wilken and Wardlaw 2010, Appendix 2); however, no Vandenberg monkeyflower were seen. At some point prior to 1931, seed from Burton Mesa may have blown downwind to this location, but it appears that Vandenberg monkeyflower has been extirpated at this location because no suitable habitat remains due to agricultural conversion (including vineyards and berries (Elvin 2009, pers. obs.) and heavily grazed pastureland (Wilken and Wardlaw 2010, Appendix 2). Therefore, we consider the occurrence of Vandenberg monkeyflower to be extirpated from this location.

The second historical collection of Vandenberg monkeyflower was made in 1960 near lower Pine Canyon (part of the existing Pine Canyon occurrence) on the eastern edge of Vandenberg AFB (Jepson Herbarium 2006; Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 2006). Vandenberg monkeyflower had not been documented since it was collected there in 1960; however, it was observed in 2010 and 2012 up-canyon from this historical location (Lum in litt. 2012a, Rutherford in litt. 2012) where suitable habitat remains. (See further discussion of Pine Canyon in Current Locations section below). The description of the location of this historical occurrence is not precise enough to determine that the location is distinct from, and not part of, the location where an extant occurrence was observed in 2010 and 2012 in upper Pine Canyon (See Occurrences Located on Vandenberg AFB section below). Therefore, we consider the historical occurrence of Vandenberg monkeyflower to be part of the extant Pine Canyon occurrence.

The third historical location of Vandenberg monkeyflower was observed, but not collected, in 1985 in the southwestern portion of the Vandenberg Management Unit on the Reserve (Hickson in litt. 2007). Although no collection was made, we have a high confidence in the accuracy of the observation (known as the Lower Santa Lucia Canyon occurrence; Figure 2) because it was made during the course of a vegetation study for a master's thesis (Hickson in litt. 2007). The location had not been searched for the species between 1985 and 2011; in 2012 (a low rainfall year), CDFW staff (Meyer) conducted a cursory survey and was unable to relocate the species (Meyer in litt. 2012c). Because it has been approximately 30 years (albeit with little survey effort between 1985 and 2011) since it was last observed, and suitable habitat remains but is overcrowded with invasive, nonnative plants (see Factor A—Invasive, Nonnative Plants), we consider the occurrence of Vandenberg monkeyflower at this historical location to be potentially extirpated.

Current Status of Vandenberg Monkeyflower

Because we do not have a wealth of survey data over multiple years to analyze a trend in the long-term persistence of Vandenberg monkeyflower, we consider it most appropriate to use suitable habitat trends as a surrogate for the species' trend. Thus, an increase or decrease in the amount of suitable habitat likely results in a respective increase or decrease in the Vandenberg monkeyflower population.

Surveys for Vandenberg monkeyflower have occurred across this species' range on Burton Mesa during recent years, although the level of effort and precision of the surveys varied between the different biologists who conducted surveys. In 2006, the first year that a concerted effort was made to survey most of the known locations, approximately 2,700 individuals were observed during surveys throughout the known range of the species (Ballard 2006; Wilken and Wardlaw 2010, pp. 2-3, Appendices 1, 2). In 2010, the Air Force observed approximately 5,200 individuals during surveys conducted on 376 ac (152 ha) within Vandenberg AFB (Air Force 2012).

In other years, individuals and agencies (including Air Force, CDFW, and our biologists) have conducted opportunistic surveys of specific sites where this species occurs, but rangewide surveys have not been conducted since 2006. Ballard (in litt. 2009) searched for Vandenberg monkeyflower in areas between extant occurrences and on the periphery of the plant's known distribution but found no plants. Additionally, the species has not been observed in some areas with sandy openings that appear to be suitable habitat (Ballard in litt. 2009). These areas: (1) Appear slightly degraded, even though many species commonly associated with Vandenberg monkeyflower were often abundant; (2) contain small pockets of sandy openings, but the sands did not appear to contain a loose enough structure to support Vandenberg monkeyflower; or (3) harbor a dominant amount of invasive, nonnative plants within sandy openings. The ability for Vandenberg monkeyflower to grow in sandy openings may depend upon the stand age and disturbance history of the location, as well as edaphic factors (Davis et al. 1988, p. 188), along with the amount of rainfall, size of the seed bank, and competition with invasive, nonnative plants.

The following sections provide a description of nine specific locations (which contain all extant occurrences identified in Figure 2) where Vandenberg monkeyflower is known to occur, hereby referred to as nine occurrences. All known occurrences are on the following lands: Vandenberg AFB (four occurrences), Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve (three occurrences), and La Purisima Mission SHP (two occurrences) (See Figure 2; Table 1).

Table 1—Vandenberg Monkeyflower Locations, Land Ownership, and Current Status

Vandenberg monkeyflower locations Land ownership Current status Current Locations 1. Oak Canyon Vandenberg AFB Extant. 2. Pine Canyon (includes historical location in lower Pine Canyon) Vandenberg AFB Extant. 3. Lake Canyon Vandenberg AFB Extant. 4. Santa Lucia Canyon Vandenberg AFB Extant. 5. Volans Avenue Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve Extant. Start Printed Page 64848 6. Clubhouse Estates Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve and Private lands Extant. 7. Davis Creek Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve Extant. 8. La Purisima West La Purisima Mission State Historic Park Extant. 9. La Purisima East La Purisima Mission State Historic Park Extant. Historical Locations Santa Rita Valley Private lands Extirpated. Lower Santa Lucia Canyon Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve Potentially Extirpated. Occurrences Located on Vandenberg AFB

There are four locations on Vandenberg AFB that are known to support occurrences of Vandenberg monkeyflower. We refer to these four locations as the Oak, Pine, Lake, and Santa Lucia Canyons occurrences.

(1) Oak Canyon. Vandenberg monkeyflower was reported as common in the late 1980s or early 1990s (Odion in litt. 2006) at the mouth of Oak Canyon on the eastern edge of the Base. Four individuals were found in 2006 (Ventura Fish and Wildlife Herbarium (VFWO) 2013). Although no plants were found in 2010 or 2012 (Air Force 2012, p. 1; Lum in litt. 2012b; Rutherford in litt. 2012), as discussed above in the Background—Life History section, we consider the species to be extant at this location because it has only been 7 years since individuals were last seen, and it is likely that a residual seed bank is still present.

(2) Pine Canyon. Approximately 365 individuals were present in multiple scattered occurrences in upper Pine Canyon in 2010 (Lum in litt. 2012b), and approximately 100 individuals were observed in 2012 (Rutherford in litt. 2012).

(3) Lake Canyon. This occurrence contains the greatest number of individuals throughout this species' range and accounts for most of the individuals on Vandenberg AFB. Approximately 1,500 individuals were observed in 2006 and 1,000 individuals in 2007 (Elvin in litt. 2009; VFWO 2013). The most recent surveys in Lake Canyon occurred in 2010 and documented approximately 4,817 individuals (Lum in litt. 2012b), although these surveys likely included a larger portion of the canyon than surveys conducted in 2006 and 2007. Even though surveys have not occurred at this location since 2010, plants were also observed at several sites in Lake Canyon in 2012. Therefore, we consider the species to be extant at this location (Rutherford in litt. 2012). A seed bank is likely present.

(4) Santa Lucia Canyon. This canyon is located on the eastern edge of Vandenberg AFB at the junction of Santa Lucia and Lakes Canyons and abuts the Reserve that lies to the east. Approximately 25 individuals were observed in 2006 (Ballard 2006), and 1 individual was observed in 2010 (Lum in litt. 2012b). Although surveys have not occurred at this location since 2010, we consider the species to be extant at this location because it has only been 3 years since the species was last seen, and it is likely that a residual seed bank is still present.

Occurrences Located on Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve

Vandenberg monkeyflower occurs or partially occurs (i.e., part of the occurrence is on the Reserve and part of the occurrence is off the Reserve) at three locations within the Reserve. We refer to these locations as the Volans Avenue, Clubhouse Estates, and Davis Creek occurrences.

(5) Volans Avenue. Individuals of Vandenberg monkeyflower have been observed in the Santa Lucia Management Unit of the Reserve immediately west of Volans Avenue, between a portion of Vandenberg Village and California State Highway 1. The Santa Lucia Management Unit abuts the eastern boundary of Vandenberg AFB. Five plants were observed in 2003, and one plant was observed in 2007 (Meyer in litt. 2007). In the other years between 2004 and 2006, and in 2009, no plants were found (Meyer in litt. 2007; Ballard in litt. 2007; Meyer in litt. 2009a). Although no surveys have occurred since 2009, we consider the species to be extant at this location because it has only been 6 years since individuals were last seen, and it is likely that a residual seed bank is still present.

(6) Clubhouse Estates. Vandenberg monkeyflower occurs east of Vandenberg Village on both the privately owned Clubhouse Estates residential development project site, which has ongoing but differing levels of development since 2006, and an adjacent portion of the Encina Management Unit of the Reserve. Prior to 2006, most of the plants occurred on private property at the Clubhouse Estates project site (Scientific Applications International Corporation (SAIC) 2005b, Figure 4.3-2). Approximately 100-285 individuals were observed in 2006 (Wilken and Wardlaw 2010, Appendices 1, 2), and approximately 350-400 individuals were observed in 2009 (McGowan in litt. 2009). Although no surveys have occurred since 2009, we consider the species to be extant at this location because it has only been 4 years since individuals were last seen, and it is likely that both plants and a residual seed bank are present.

(7) Davis Creek. Vandenberg monkeyflower is located along the western border of the Encina Management Unit of the Reserve and a right-of-way (ROW) for California State Highway 1 managed by the California Department of Transportation. Davis Creek is east of Vandenberg Village and less than 1 mi (1.6 km) south of the Vandenberg monkeyflower individuals at Clubhouse Estates.

The Davis Creek occurrence comprises four locations where Vandenberg monkeyflower has been observed. At “west of Highway 1,” researchers reported 3 individuals in 2006 (Ballard 2006), approximately 100 in 2009 (Rutherford and Ballard in litt. 2009), and 60 in 2010 (Meyer in litt. 2010a). At “north of Burton Mesa Boulevard,” four individuals were observed in 2006 (Ballard 2006), and seven individuals were observed in 2010 (Meyer in litt. 2010a). Subsequently, 180 individuals were observed in 2010 at a third location east of the Vandenberg Village Community Services District Pump Station and between Highway 1 and Burton Mesa Boulevard (Meyer in litt. 2010a). Similarly, approximately 500 Start Printed Page 64849individuals were observed in 2010 at a fourth location northwest of the location where 180 individuals were observed in 2010, and to the west of the 7 individuals observed in 2010 that were located north of the Burton Mesa Boulevard. Individuals were also observed at several of these locations in 2012 and 2013. We consider the species to be extant at this location because individuals have been seen as recently as 2013 (Meyer in litt. 2013).

Occurrences Located on La Purisima Mission SHP

Vandenberg monkeyflower occurs at two separate locations within La Purisima Mission SHP. We refer to these locations of Vandenberg monkeyflower as the La Purisima West and La Purisima East occurrences.

(8) La Purisima West. Vandenberg monkeyflower that occur on the west side of the park are located in a discrete location. Approximately 300 individuals were observed in 2006 (Ballard 2006), and approximately 1,500 individuals were observed in 2009 (Rutherford and Ballard in litt. 2009). Subsequently, individuals were observed here in 2010 and 2011 but not counted (Rutherford in litt. 2012). Although no observations have occurred since 2011, we consider the species to be extant at this location because it has been only 2 years since individuals were last observed (although not counted), and it is likely that both plants and a residual seed bank are present.

(9) La Purisima East. Vandenberg monkeyflower that occur on the east side of the park are made up of hundreds of scattered individuals. Approximately 850 individuals were observed in 2006 (Ballard 2006) and approximately 400 individuals were observed in 2009 (Rutherford and Ballard in litt. 2009). Although no surveys have occurred since 2009, we consider the species to be extant at this location because it has been only 4 years since individuals were last seen, and it is likely that both plants and a residual seed bank are present.

Summary—Distribution and Status of Vandenberg Monkeyflower

In summary, we identified one extirpated location where Vandenberg monkeyflower no longer exists, one location that is considered potentially extirpated, and nine locations where Vandenberg monkeyflower is currently considered extant on Burton Mesa. Most of these extant locations contain multiple scattered individuals, and thus we refer to these areas as nine occurrences, as defined above. We generally characterized the size of Vandenberg monkeyflower occurrences based on multiple observations over a period of years. Two of the nine occurrences (22 percent; Lake Canyon and La Purisima West) each contained over 1,000 individuals in multiple years and are the two largest known occurrences of this species. These largest occurrences include a high of approximately 1,500 individuals at Lake Canyon in 2006 (Elvin in litt. 2009; VFWO 2013) and 1,500 individuals at La Purisima West in 2009 (Rutherford and Ballard in litt. 2009). Four occurrences (44 percent; Pine Canyon, Clubhouse Estates, Davis Creek, and La Purisima East) each contained hundreds of plants ranging between 100 and 850 individuals in multiple years. Finally, three occurrences (33 percent; Oak Canyon, Santa Lucia Canyon, and Volans Avenue) are the smallest, with a range of no individuals observed in most years surveyed (Volans Avenue) to a high of 25 individuals observed in 2006 (Santa Lucia Canyon). Although trend data are not available, these data indicate that the aboveground expression of Vandenberg monkeyflower for 7 of the 9 occurrences (78 percent) harbor 850 or fewer individuals.

Because we have only one rangewide survey for this species, and because based on our current data and the likelihood that Vandenberg monkeyflower forms a seed bank and expresses variable numbers of aboveground individuals from year to year (see Background—Life History section above), we are unable to determine a trend in the Vandenberg monkeyflower population. Therefore, we will use trends in the amount of suitable habitat as a surrogate for the species' trend.

Summary of Factors Affecting the Species

Section 4 of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533), and its implementing regulations at 50 CFR part 424, set forth the procedures for adding species to the Federal Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. Under section 4(a)(1) of the Act, we may list a species based on any of the following five factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. Listing actions may be warranted based on any of the above threat factors, singly or in combination. Each of these factors is discussed below.

Factor A. The Present or Threatened Destruction, Modification, or Curtailment of Its Habitat or Range

Factor A threats to Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat include development (military, State lands, and residential), utility maintenance and miscellaneous activities, invasive, nonnative plants, anthropogenic (influenced by human-caused activity) fire, recreation, and climate change. These impact categories overlap or act in concert with each other to adversely affect Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat.

Development—Military

Development of Vandenberg AFB military facilities within the last century directly removed approximately 6,104 ac (2,470 ha) of Burton Mesa chaparral habitat. Approximately 40 percent of the chaparral that historically occurred on Vandenberg AFB remains, mostly south and east of the primary developed area on Vandenberg AFB (Odion et al. 1992, p. 12). West of the developed area has been impacted by numerous trails, roads, and other ground disturbances. Much of the chaparral habitat that once existed to the north of the primary developed area was cultivated or type-converted (disturbance resulting in a new dominant plant community) to rangeland prior to military use. Areas that historically consisted of chaparral vegetation have regenerated to nonnative grassland, usually with shrubs, and are no longer considered suitable habitat for Vandenberg monkeyflower. This nonnative grassland is dominated by veldt grass and several species of nonnative annual grasses including Bromus spp. (bromes), Avena spp. (oatgrass), and Vulpia spp. (silvergrass) (Odion et al. 1992, p. 11).

The Air Force maintains multiple launch facilities at Vandenberg AFB to accomplish their mission (Air Force 2011c, p. 7). There are no launch facilities in suitable habitat for Vandenberg monkeyflower, and the Air Force is not likely to construct new launch facilities within suitable habitat because potential construction would likely occur near the coastline and away from more inland, human-populated areas (Air Force 2009a, p. 16). Additionally, the siting of future facilities is expected to capitalize on existing infrastructure; therefore, disturbance in undeveloped areas would be minimized (Air Force 2009a, p. 32).Start Printed Page 64850

Development—State Lands

Prior to the State Lands Commission acquisition of the Reserve lands in 1990, four land uses were identified in the Reserve area, including agricultural operations, military operations, extractive industries, and urban development (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 54). The Reserve encompasses 5,186 ac (2,099 ha) and there has been no threat from new development. However, local governmental agencies and public utility companies maintain existing utilities and easements throughout the Reserve (see Factor A—Utility Maintenance and Miscellaneous Activities below).

La Purisima Mission SHP has operated as a State Park since 1937 (California State Parks 1991, p. 107). The current park boundaries encompass a total of 1,900 ac (769 ha). The park unit consists of the historical area, natural area with riding and hiking trails, agriculture, and the maintenance/service and residential area. The total amount of native vegetation is approximately 1,770 ac (716 ha) (Service 2013, unpublished data). There is no current or future threat of habitat destruction from development at La Purisima Mission SHP because the park was established to preserve cultural and natural features of the area.

Development—Private Lands

Three residential communities exist on Burton Mesa east of Vandenberg AFB's boundary including Vandenberg Village, Mission Hills, and Mesa Oaks. These communities harbor associated infrastructure (including major roads such as California State Highway 1, Harris Grade Road, Rucker Road, and Burton Mesa Boulevard), all of which fragment the Burton Mesa chaparral. Vandenberg Village and associated golf course comprise approximately 720 ac (291 ha). Thus, at least 2,000 ac (809 ha) of Burton Mesa chaparral habitat were removed as a result of past development of these three residential communities and their associated infrastructure.

Presented below are three currently approved or proposed projects on private lands that harbor suitable Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat. Data are not available on the specific acreage of sandy openings expected to be lost as a result of these projects, but data are provided on the loss of Burton Mesa chaparral and the number of individuals of Vandenberg monkeyflower observed at, or adjacent to, these project sites.

(1) Clubhouse Estates is a private development located east of Vandenberg Village (LFR, Inc. 2006, p. 1). Santa Barbara County approved the Clubhouse Estates housing development in August 2005 (County of Santa Barbara Planning Commission 2005, p. 4). Approximately 33 ac (13 ha) were proposed to be developed into residential lots; the remaining 120 ac (49 ha) was proposed as open space (LFR, Inc. 2006, p. 1). Most of the Vandenberg monkeyflower individuals known to occur at this location were inside or within 10 ft (3 m) of the approved development footprint that was graded (SAIC 2005b, Figure 4.3-2). Additionally, the ground disturbance increased the extent of invasive, nonnative species at this location, particularly Sahara mustard and veldt grass (Meyer in litt. 2010b).

(2) The Burton Ranch Specific Plan site (Burton Ranch) is located south of the Encina Management Unit of the Reserve. The project was approved in 2006 (City of Lompoc 2012) and totals 149 ac (60 ha). Approximately 83 ac (34 ha) of Vandenberg monkeyflower suitable habitat would be removed (SAIC 2005a, p. 175). Vandenberg monkeyflower has not been observed at this site, although the habitat contains many species commonly associated with Vandenberg monkeyflower (SAIC 2005a, p. 174), and veldt grass is present within the project site. Ground disturbance expected as a result of this approved project would remove native vegetation and may create open areas where veldt grass could invade (see Factor A—Invasive Nonnnative Species below ).

A 100-ft (30-m) buffer at the northern boundary of the project site and 8 ac (3 ha) of onsite open space were proposed as part of the Burton Ranch project (SAIC 2005a). Preserving chaparral may reduce the potential of nonnative plants to invade the intact Burton Mesa chaparral in the Reserve directly to the north of this project site. Additionally, the project proponent completed a conservation agreement with the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County (Land Trust) to mitigate for the removal of native vegetation (Feeney in litt. 2012). The conservation area is known as the Burton Ranch Chaparral Preserve and encompasses 95 ac (38 ha) of Burton Mesa chaparral near Vandenberg Village.

(3) Allan Hancock College proposed to develop a public safety complex adjacent to their existing facilities and south of the Davis Creek corridor (Allan Hancock College 2009, p. 28). The project site would remove approximately 59 ac (16 ha) of Burton Mesa chaparral (Allan Hancock College 2009, pp. 134-135). Vandenberg monkeyflower has not been observed within this project site, although a few individuals were observed in 2009 within the chaparral vegetation (Allan Hancock College 2009, p. 113). Therefore, ground disturbance would remove suitable Burton Mesa chaparral and may create open areas for veldt grass to invade. As part of this project, Allan Hancock College proposed to preserve approximately 65 ac (26 ha) of Burton Mesa chaparral near the Davis Creek drainage that is contiguous with the northern portion of the project site (Allan Hancock College 2009, pp. 9, 135). Preserving chaparral in this area may reduce the potential of nonnative plants to invade the intact Burton Mesa chaparral in the Reserve to the north of this project site.

In summary, the majority of development on Vandenberg AFB and the residential communities of Vandenberg Village, Mission Hills, and Mesa Oaks, and the existing infrastructure at La Purisima Mission SHP have existed for decades. Most of Burton Mesa is either State or Federal land on which future development is unlikely; therefore, most of the remaining habitat for Vandenberg monkeyflower would not be directly impacted by future development. However, three recent private developments on the periphery of the State or Federal land either have resulted in or will result in the direct loss of Burton Mesa chaparral. Development within or adjacent to suitable chaparral habitat increases the likelihood of introducing invasive, nonnative species to spread, which is the most significant threat to Vandenberg monkeyflower (see Factor A—Invasive, Nonnative Plants). Available conservation measures to minimize the threat of development are discussed below, see Factor A—Conservation Measures Undertaken.

Utility and Pipeline Maintenance

Utility and pipeline structures occur within the Reserve on Burton Mesa. These existing facilities or structures at times require maintenance to ensure proper operation. As a result, vehicles and foot traffic could occur at or adjacent to these structures and potentially result in trampling of habitat and other soil surface disturbance, which in turn could result in ground disturbance that removes Burton Mesa chaparral and creates open areas in the vegetation that act as pathways for nonnative plants to expand or invade.

Plains Exploration and Production Company (PXP) owns an oil processing plant surrounded by the La Purisima Management Unit of the Reserve (see Land Ownership section above), and requires access to their operation across Reserve lands north of the La Purisima Start Printed Page 64851and Santa Lucia Management Units. Eighteen separate easements and 5 connector easements are used to maintain, repair, replace, and install roads and access power lines, utility lines, and pipelines (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 12). These easements are generally 50 ft (15 m) wide and vary in length. Additionally, PXP operates a triplet pipeline that is located within the 100-ft- (30-m-) wide fuel break between the Vandenberg AFB boundary and the western edge of the Reserve. Plains Exploration & Production routinely conducts maintenance of this pipeline that includes excavating trenches alongside the pipeline to perform the necessary inspections and repairs. The Oak Canyon occurrence of Vandenberg monkeyflower on Vandenberg AFB is partially located within the pipeline's footprint. No monkeyflower individuals have been observed in Oak Canyon recently, and veldt grass has filled almost every opening in the scrub in Oak Canyon (Rutherford in litt. 2012) (see Factor A—Invasive, Nonnative Species). The Santa Lucia Canyon occurrence is adjacent to, but not within the pipeline corridor. Actions within PXP's pipeline footprint may result in ground disturbances that create openings for nonnative plants to invade and outcompete native vegetation. However, there is no indication that maintenance of PXP's pipeline in this area has affected Vandenberg monkeyflower or its habitat.

The Reserve contains a limited number of existing structures, most of which are remnants of previous land uses. Local land use agencies and public works agencies retain utilities and pipelines, and easements for access; routine maintenance of the utilities is conducted as needed. The Vandenberg Village Community Services District (VVCSD) has several structures (including water tanks, a water processing plant, wells, and water lines and sewer lines) located within the Reserve (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 63). The occurrence of Vandenberg monkeyflower at Volans Avenue is adjacent to a sewer line easement held by the VVCSD. A portion of the Vandenberg monkeyflower occurrence located at Davis Creek is within a water line easement, also held by the VVCSD. There is no indication that maintenance of VVCSD infrastructure has affected Vandenberg monkeyflower or its habitat at either of these locations.

The VVCSD filed a request with the State Lands Commission in May 2010 to acquire 27 ac (11 ha) of land within the Reserve east of their existing water tanks for the construction of a replacement water well (VVCSD 2010). The 27-ac (11-ha) site is within the Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve and is currently leased to the CDFW. Approximately 180 Vandenberg monkeyflower individuals (see the Davis Creek occurrence discussion under the Occurrences Located on Burton Mesa Ecological Reserve section above) were observed in 2010 within the 27-ac (11-ha) parcel of land where the VVCSD proposes to construct wells in the future. Therefore, if development occurs at this parcel, habitat associated with approximately 25 percent of the known individuals of Vandenberg monkeyflower that were observed in 2010 within the Davis Creek occurrence could be impacted (Meyer in litt. 2010a) (see Factor E—Utility and Pipeline Maintenance section below). Additionally, removing vegetation would create open space for nonnative plants to invade this area.

In summary, there is no indication that ongoing maintenance activities of existing pipelines and utilities have directly impacted Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat. However, utility maintenance actions could result in ground disturbance that removes Burton Mesa chaparral, creating open areas in the vegetation that act as pathways for nonnative plants to invade.

Invasive, Nonnative Species

Invasive, nonnative plants occur throughout Burton Mesa and represent the greatest threat to the remaining individuals of, and suitable habitat for, Vandenberg monkeyflower. Invasive, nonnative plants occur across Vandenberg monkeyflower's range, including within and adjacent to occupied habitat at all nine extant locations, as well as at the potentially extirpated location (Lower Santa Lucia Canyon). The presence of invasive, nonnative plants can alter all components of an ecosystem, from directly altering habitat and displacing individuals (the latter of which is described under Factor E), to negatively affecting the abundance and diversity of small mammals and insects that disperse seeds or pollinate the native vegetation.

Disturbance is one of the primary factors that promote invasion of nonnative species (Rejmanek 1996; D'Antonio and Vitousek 1992; Hobbs and Huenneke 1992; Brooks et al. 2004; Keeley et al. 2005). Broad disturbances such as urban development, and disturbances along corridors, such as roadsides and trails, provide opportunities for nonnative plants to invade and gain a foothold in Burton Mesa (Keil and Holland 1998, p. 23). The primary fragmenting (disturbance) event can be the construction of a road, with or without associated housing development; later the habitat remnants are subdivided by additional development, or trails and smaller disturbances that occur within the habitat remnants (Soule et al. 1992, p. 43). It is well known that roadside edges tend to be highly invaded habitats (Gelbard and Belnap 2003, p. 422). Paved roads tend to have larger verges and more adjacent invasive plants present than unpaved roads because of the ongoing maintenance and improvements of paved roads (Gelbard and Belnap 2003, pp. 422-430). Additionally, wheeled vehicles effectively disperse seed and seed-bearing plant parts along travel routes and trails, helping to spread invasive, nonnative plants (Gelbard and Belnap 2003; Gevirtz et al. 2005, p. 225). Several native mammals also disperse seeds of nonnative plants (D'Antonio 1990, pp. 697-698), including deer (Odocoileus spp.) and rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.), which effectively disperse the seeds in feces (Odion et al. 1992, pp. 1, 27). Furthermore, the prevailing onshore winds contribute to the rapid spread of nonnative plants across Burton Mesa.

The expansion of nonnative plants represents a substantial problem as it displaces native vegetation on Burton Mesa. Keil and Holland (1998, p. 27) documented 220 nonnative plant species on Vandenberg AFB, the majority of which are native to the Mediterranean region and a smaller number native to Eurasia, South America, Australia, South Africa, or other regions. A total of 124 nonnative plant species were observed on the Reserve, 17 of which are recognized as high concern because of their severe ecological impacts on native ecosystems (Gevirtz et al. 2007, p. 181). Ferren et al. (1984, p. 75) documented 90 species of nonnative plants in La Purisima Mission SHP, comprising approximately 25 percent of the total flora at the park. The list of species observed by Ferren et al. (1984) is not comprehensive but includes nearly all species occurring on unplowed uplands of Burton Mesa where Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat occurs (Hickson 1987, p. 21).

Several invasive plant species that are present within Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat and of particular concern with regard to altering habitat of Vandenberg monkeyflower on Burton Mesa include veldt grass, pampas grass, bromes, Sahara mustard, Centaurea solstitialis (star thistle), iceplant, Carduus pycnocephalus (Italian thistle), and Cirsium vulgare (bull thistle). The first five of these species have a ranking of “A” by the California Invasive Plants Start Printed Page 64852Council (Cal-IPC), denoting the highest level of impact on native habitats; iceplant, Italian thistle, and bull thistle have a ranking of “B”, denoting a moderate level of impact on native habitats (Cal-IPC 2012).

The following paragraphs include a brief discussion of four prolific invasive, nonnative plants (veldt grass, iceplant, Sahara mustard, and pampas grass) that are having the greatest impact to Vandenberg monkeyflower occupied and suitable habitat across its range. We describe general biological impacts these four invasive plants have on native vegetation, including known impacts to Burton Mesa chaparral, and thus, suitable habitat for Vandenberg monkeyflower. We then discuss the specific presence and known impacts of these invasive plants on Burton Mesa chaparral at each of the nine extant Vandenberg monkeyflower locations and one potentially extirpated location. We describe the biological impacts using the best available information, which includes personal observations of many scientists who are local experts concerning Burton Mesa or Vandenberg monkeyflower and its habitat. Available conservation measures to minimize the threat of invasive, nonnative plants are discussed below under Factor A—Conservation Measures Undertaken.

(1) Veldt Grass. Veldt grass may be the most pervasive of the nonnative species in Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat because it can produce an abundance of seeds year-round, and grows under a wide variety of light, temperature, moisture, and substrate conditions (Keil and Holland 1998, p. 23; The Nature Conservancy (TNC) 2005, pp. 6-7). Additionally, it is extremely difficult to eradicate once established. Note that, while several species of veldt grass occur in this region, the most prevalent, and the one we are focusing on in this rule, is South African perennial veldt grass. As a sprawling perennial, veldt grass substantially changes the plant community composition in invaded habitats, altering fire potential by buildup of dense thatch during the summer months (see Factor A—Anthropogenic Fire), and increasing the rate of organic matter accumulation (TNC 2005, p. 6; Cal-IPC 2012). Veldt grass tends to crowd out native species and prevents the reestablishment of native herbs and shrubs; larger shrubs are not replaced after they die (Keil and Holland 1998, p. 23; Bossard et al. 2000 pp. 164-170; Earth Tech et al. 1996, p. 314). Veldt grass also readily spreads into roadsides and from there into openings between shrubs (Bossard et al. 2000, p. 168). In the absence of veldt grass, open areas that occur in native vegetative communities on the mesa tend to be occupied by a variety of native annual herbs and short-lived perennials (Earth Tech et al. 1996, p. 314). These open areas may provide habitat for Vandenberg monkeyflower.

Veldt grass is spreading rapidly across Vandenberg AFB and the Burton Mesa and represents a significant problem (Gevirtz et at. 2007, p. 181). It was established on Vandenberg AFB in the late 1950s to stabilize sand dunes in the Purisima Point area approximately 5 mi (8 km) south of San Antonio Terrace (Peters and Sciandrone 1964, pp. 98, 101); the San Antonio Terrace dune sheet overlies the western edges of Burton Mesa and is upwind of Burton Mesa (Hunt 1993, p. 8). In a study of the vegetation of San Antonio Terrace, photos from 1979 and the early 1990s were compared, noting that veldt grass had expanded from a few localized areas (generally around existing roads and buildings) to become a dominant component of the vegetation and had expanded to new areas (Earth Tech et al. 1996). Veldt grass initially invades roadway corridors or other disturbed areas, and then spreads into the more open herbaceous or unvegetated areas between shrubs (Earth Tech et al. 1996, p. 314). Grasses like veldt grass that are prolific seeders can build up a large seed bank in the soil, increasing their capacity to respond to disturbances; however, D'Antonio and Vitousek (1992, p. 66) noted that veldt grass is also a threat in the absence of habitat disturbance because it can invade undisturbed coastal habitats in California. Sandy habitats appear to be particularly susceptible to invasion in California (TNC 2005, p. 6). Human (1990, p. 34) identified veldt grass as the most devastating of the nonnative invaders on San Antonio Terrace (which is upwind of Burton Mesa and thus Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat) because it forms solid stands and excludes native plant species.

Currently, veldt grass occurs in more areas on Vandenberg AFB than where it was initially introduced. On Vandenberg AFB, veldt grass occurs both within and adjacent to occupied Vandenberg monkeyflower habitat and is expanding at Santa Lucia, Lake, and Pine Canyons, and has become the dominant vegetation cover in portions of lower Oak Canyon. Additionally, veldt grass is present and expanding at certain locations on the Reserve, including at the Volans Avenue, Clubhouse Estates, and Davis Creek occurrences. Veldt grass is also present at La Purisima Mission SHP. See section below entitled Review of Invasive, Nonnative Species Present by Occurrence regarding the presence and known impacts of veldt grass at each of the Vandenberg monkeyflower occurrences.

(2) Iceplant. Iceplant is a succulent, mat-forming perennial (D'Antonio 1990, p. 694). A single iceplant individual can form dense, circular mats up to 33 ft (10 m) in diameter and approximately 20 in (40 cm) thick (D'Antonio and Mahall 1991, p. 886). It overcrowds native plants and has an exceptional ability to spread to sandy soils along the coast (Jacks et al. 1984, p. 12; Zedler and Scheid 1988, p. 196).

The reproductive potential of iceplant is very high (Schmalzer and Hinkle 1987, p. 18). It propagates by seed and vegetatively; even small stem fragments can regenerate into a new plant (Cal-IPC 2012). Iceplant is a successful invader because seeds are dispersed before or during the time of year when they are most likely to germinate, which allows little time for post-dispersal predation to occur; and the seeds are dispersed by a diversity of mammals (D'Antonio 1990, p. 700). Additionally, Vivrette and Muller (1977, pp. 315-317) showed that the salt leached from iceplant individuals was the limiting factor in the growth and establishment of native grassland species. Salt retained in aerial parts of dried iceplant individuals is transported into the soil through leaching by fog in the summer and rain in the fall (Vivrette and Muller 1977, pp. 311, 316; Kloot 1983, pp. 304-305). On sandy soils, salt deposited in the summer is washed through the soil and replaced by the remaining lower levels of salt leaching out of the plant with the first rains in the fall (Vivrette and Muller 1977, p. 316).

Iceplant is an invasive species of great concern on Vandenberg AFB (Keil and Holland 1998, p. 22). It was originally planted on Base along roads and about buildings to prevent wind erosion (Human 1990, pp. 32, 42). By the mid-1990s, iceplant occupied hundreds of acres on the San Antonio Terrace, having spread into adjacent habitats from plantings along roadsides, the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks, and around missile testing facilities (Earth Tech 1996, p. 264). It is especially prevalent west of the main developed area on Vandenberg AFB because there is extensive iceplant in the adjacent dune habitat and former chaparral habitat, and because of extensive past mechanical disturbance (i.e., land disturbed by mechanical equipment) within the chaparral west of the primary developed area (Odion et al. 1992, p. 13).

Iceplant recruits abundantly within openings in the chaparral canopy such Start Printed Page 64853as those created by burning or mechanical disturbance (Odion et al. 1992, p. 1), and there is no area of Burton Mesa chaparral on Base where iceplant will not invade (Odion et al. 1992, p. 13). In one instance after a prescribed burn, iceplant was discovered in the burned plot after the fire, which was unexpected because succulent plants (such as iceplant) are not known to have the capacity to recover rapidly from fire (Jacks et al. 1984, pp. 11-12). Iceplant was not known to occur in the burn plot prior to fire; however, within 3 years of the prescribed burn, iceplant was the second most prevalent post-fire perennial plant observed (Zedler and Schied 1988, p. 198). Because iceplant distribution is extensive on Vandenberg AFB (Air Force 2011a) and is common within most chaparral on the Base (Odion et al. 1992, p. 13), little effort has been made to map individuals of iceplant that are mixed within many habitats on the Base, including Burton Mesa chaparral.

Iceplant has also been observed in the Reserve (Junak 2011; Meyer 2012, pers. comm.) and at La Purisima Mission SHP (Gevirtz et al. 2005, Appendix 5), although it is not as common as it is on Vandenberg AFB. Please see the Review of Invasive, Nonnative Species Present by Occurrence section below regarding the presence and known impacts of iceplant at each of the Vandenberg monkeyflower occurrences.

(3) Sahara Mustard. Dense stands of Sahara mustard have the potential to dominate native ecosystems, especially in dry sandy soils (County of Santa Barbara Agricultural Commissioner's Office (Santa Barbara Ag. Comm.) 2012). Sahara mustard is especially common in areas with wind-blown sand deposits and in disturbed sites, such as roadsides. Additionally, it is invading nonnative annual grassland and coastal sage scrub on the coastal slope of southern California and is well-established in all counties of southern California (Cal-IPC 2012). In coastal southern California, it locally dominates nonnative grasslands in dry, open sites, especially disturbed areas, and can expand over larger areas replacing other nonnative annuals during drought conditions (Cal-IPC 2012). Its early-season growth and large size allow it to monopolize early-season moisture, expand its canopy, and set seed before other plants have emerged (Cal-IPC 2012; Santa Barbara Ag. Comm. 2012; Barrows et al. 2009).