2014-27113. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for Gunnison Sage-Grouse

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 69312

AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

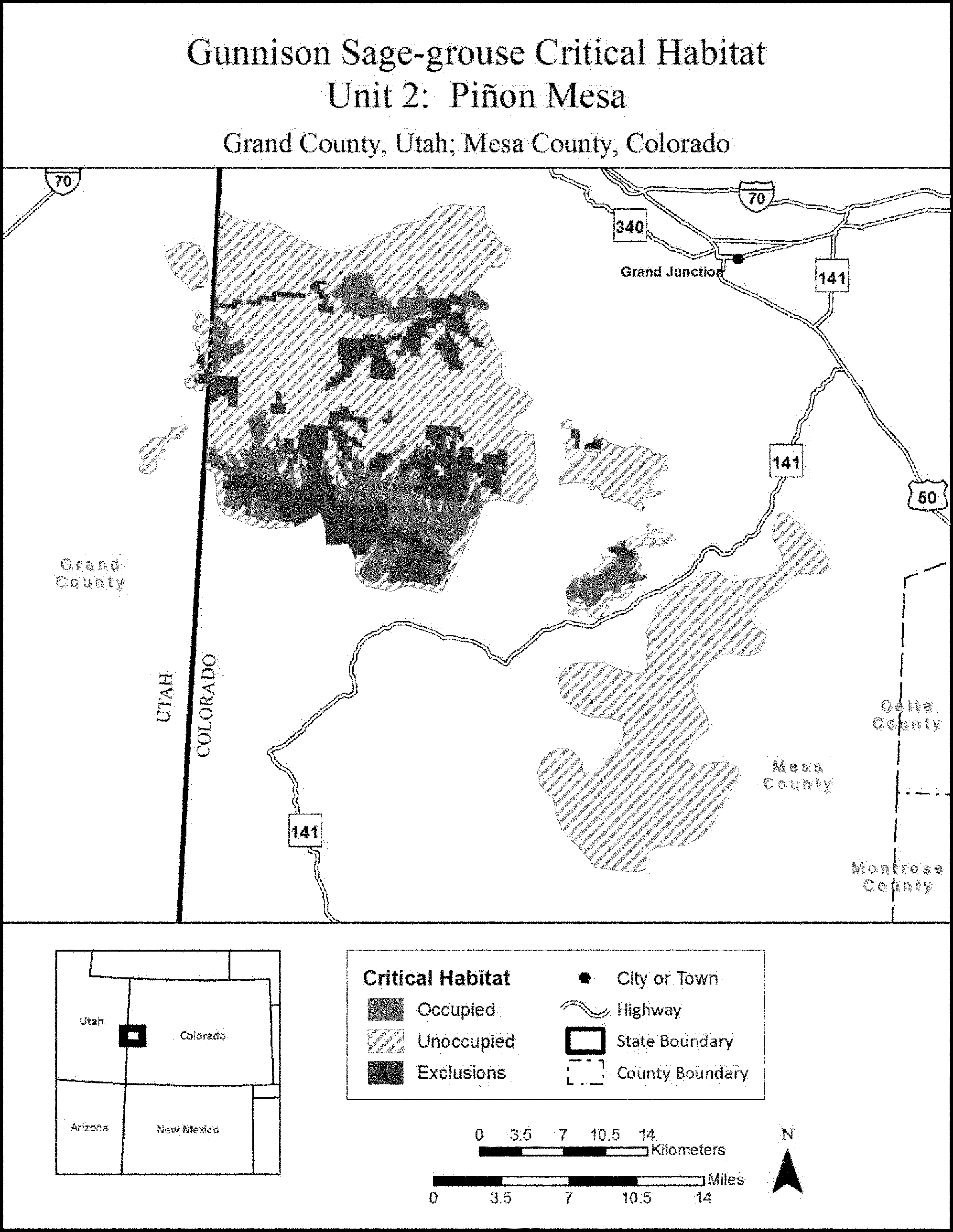

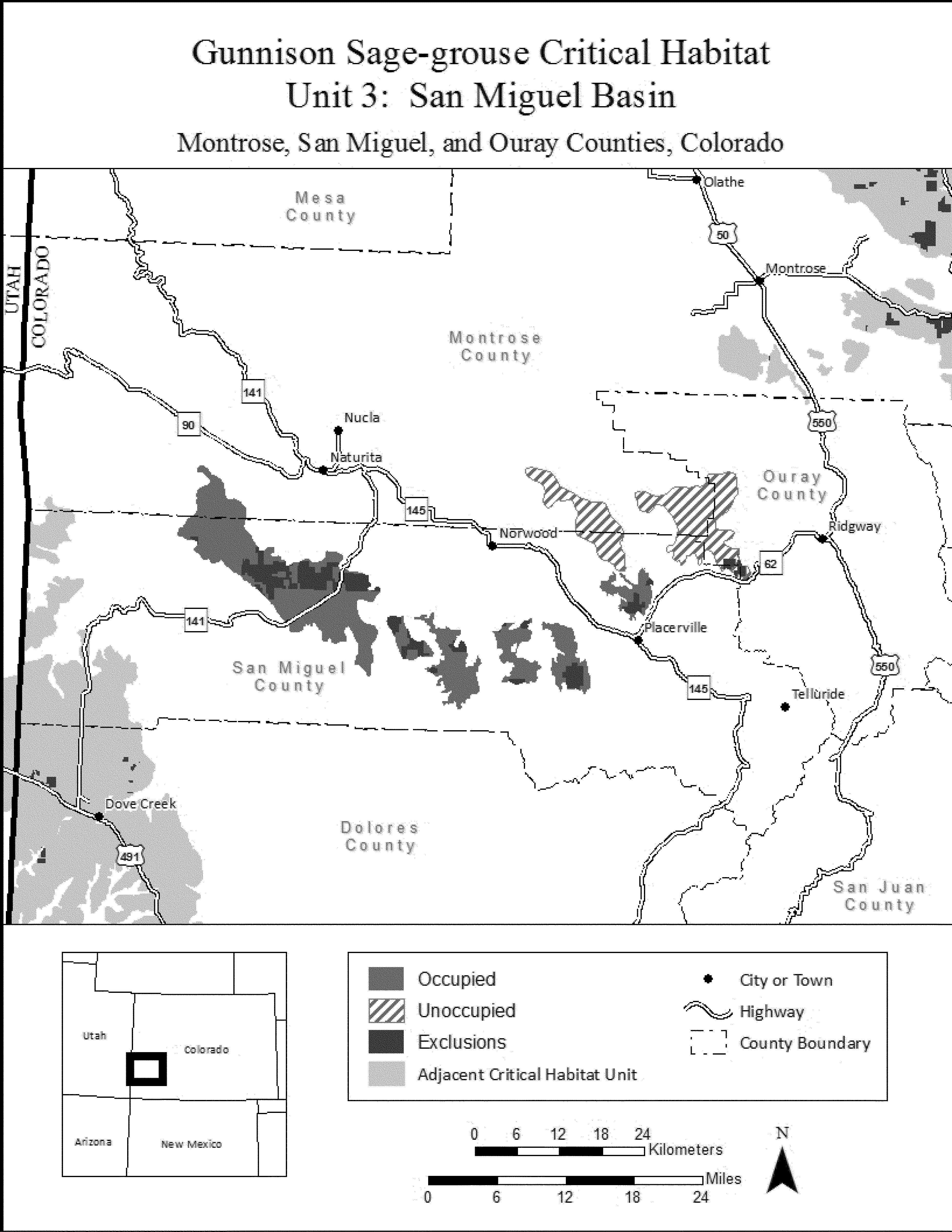

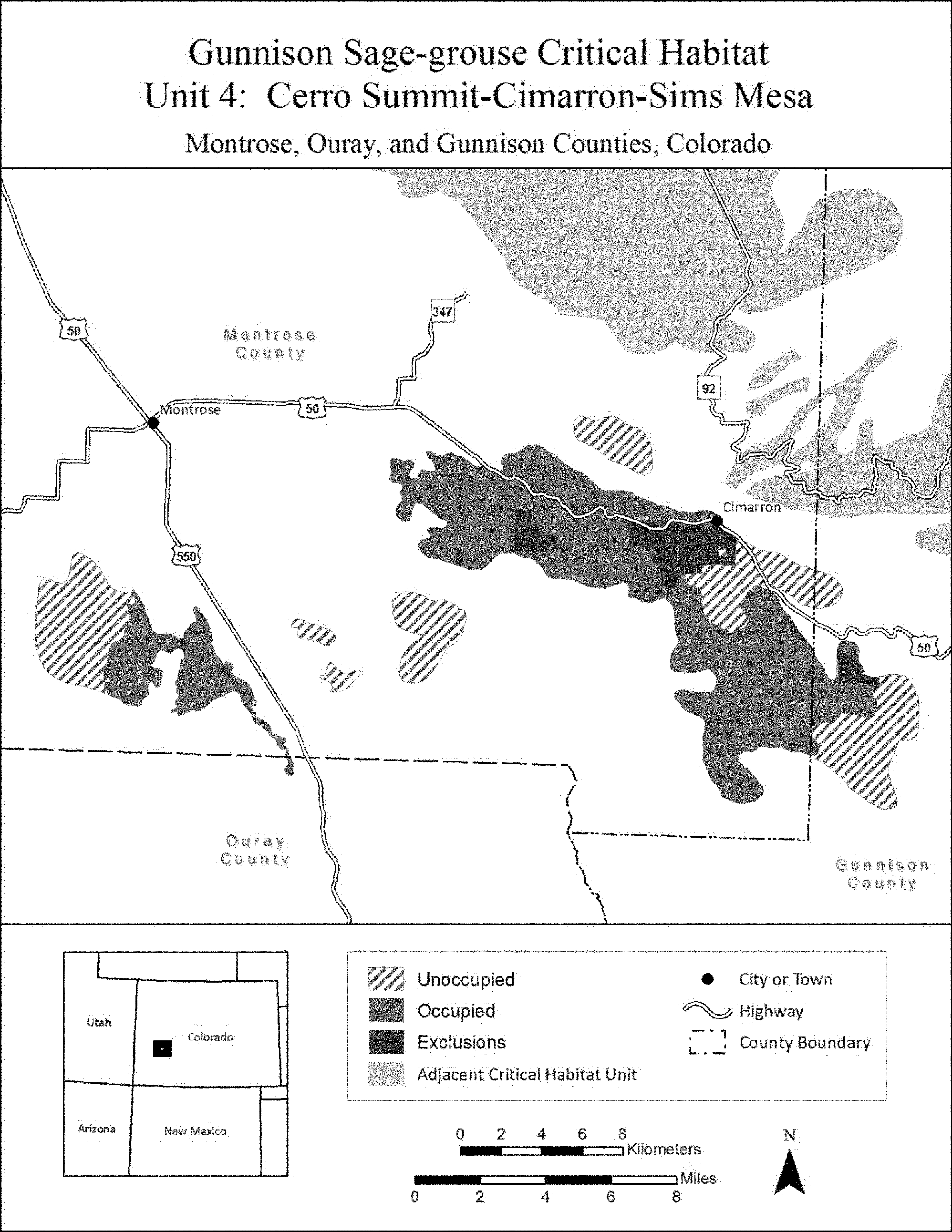

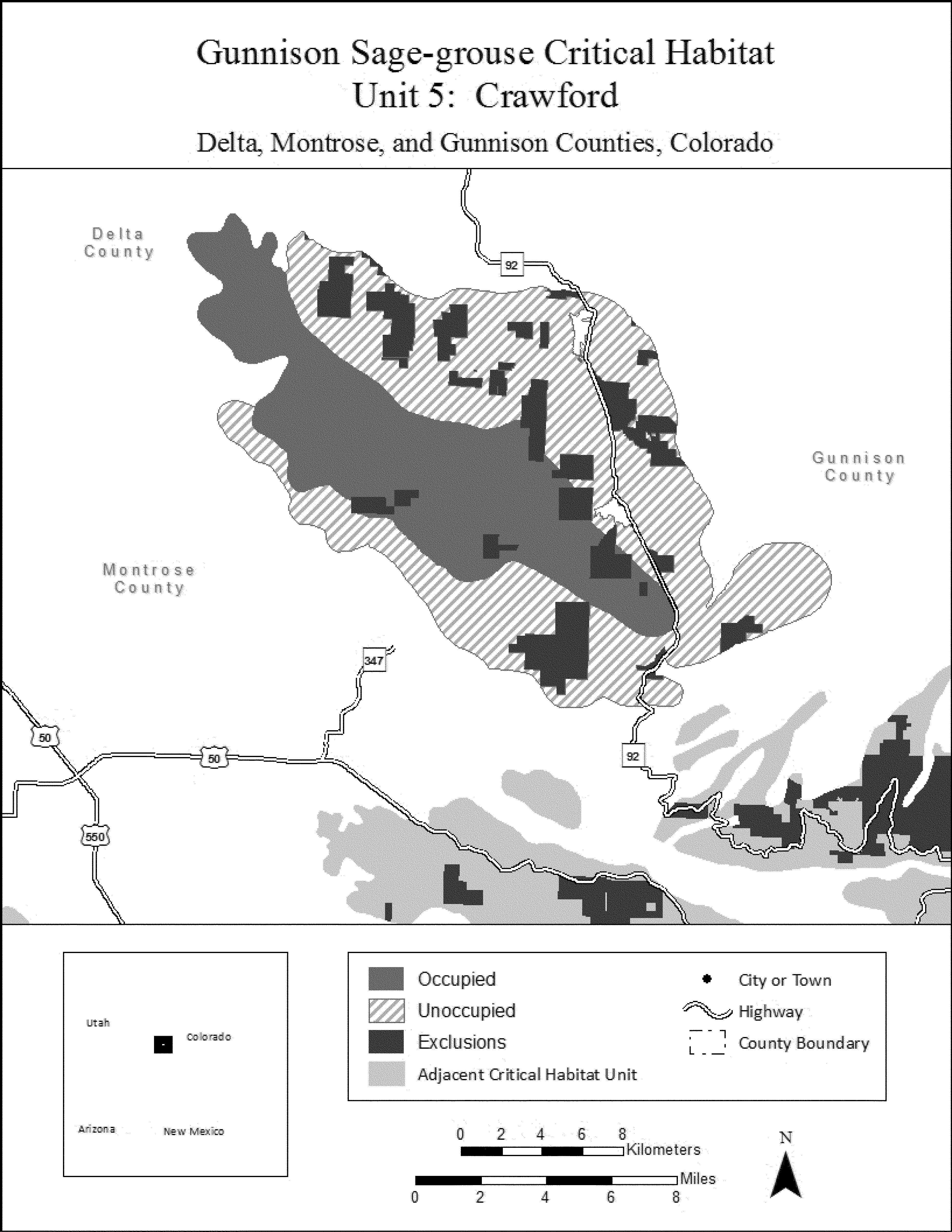

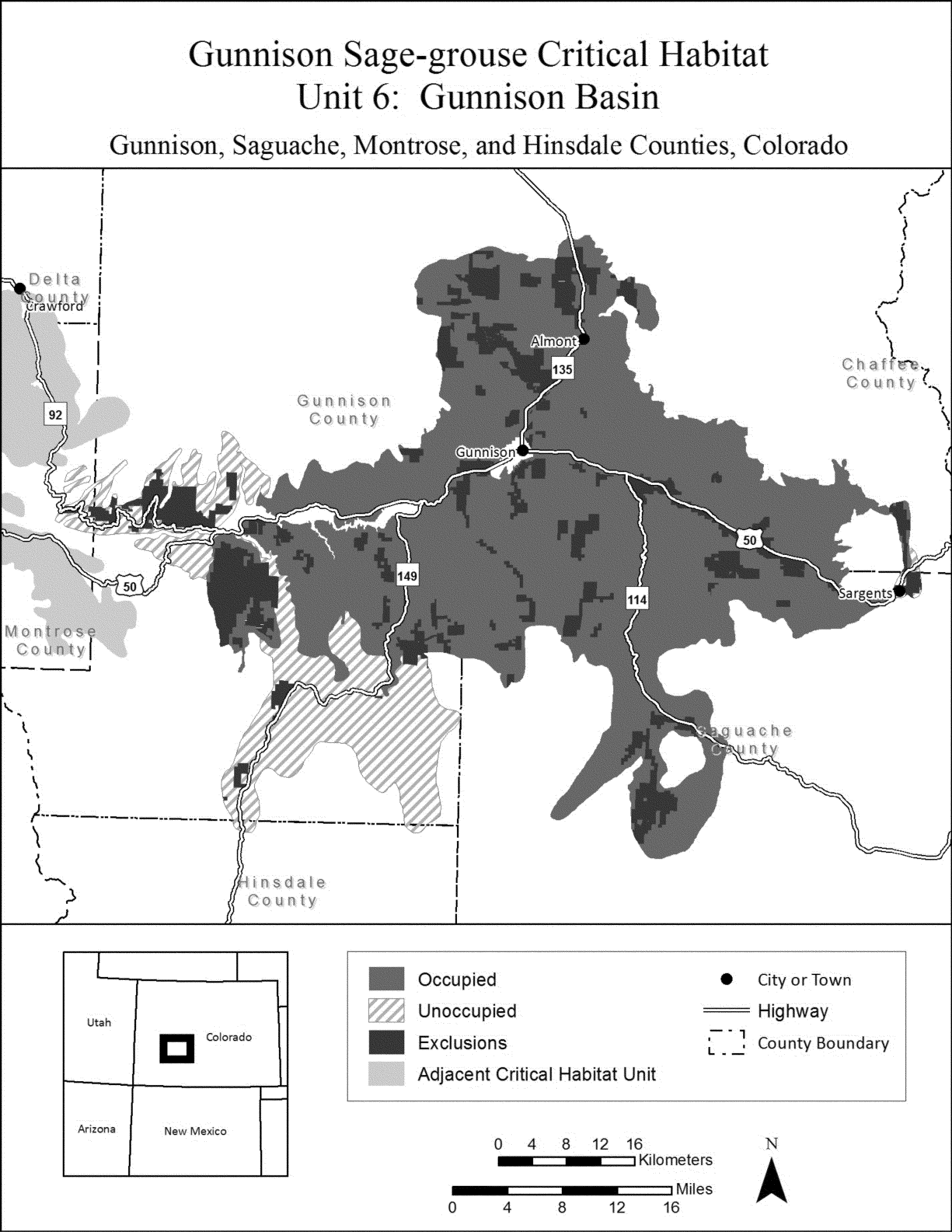

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), designate critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse (Centrocercus minimus) under the Endangered Species Act (Act). In total, approximately 1,429,551 acres (ac) (578,515 hectares (ha)) are designated as critical habitat in Delta, Dolores, Gunnison, Hinsdale, Mesa, Montrose, Ouray, Saguache, and San Miguel Counties in Colorado; and in Grand and San Juan Counties in Utah. The effect of this regulation is to conserve Gunnison sage-grouse habitat under the Act.

DATES:

This rule becomes effective on December 22, 2014.

ADDRESSES:

This final rule is available on the internet at http://www.regulations.gov and at the Service's species Web site for Gunnison sage-grouse, at http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/birds/gunnisonsagegrouse/. Comments and materials we received, as well as supporting documentation used in preparing this final rule, are available for public inspection at http://www.regulations.gov. All of the comments, materials, and documentation that we considered in this rulemaking will be made available by appointment, during normal business hours at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Western Colorado Field Office, 445 West Gunnison Ave., Suite 240, Grand Junction, CO 81501; telephone 970-243-2778.

The coordinates from which the critical habitat maps are generated are included in the administrative record for this rulemaking and are available at http://www.regulations.gov at Docket No. FWS-R6-ES-2011-0111, at http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/birds/gunnisonsagegrouse/,, and at the Western Colorado Field Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT). Any additional tools or supporting information that we developed for this critical habitat designation will also be available at the Fish and Wildlife Service Web site and Field Office set out above, and may also be included in the preamble and at http://www.regulations.gov.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Susan Linner, Western Colorado Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Western Colorado Field Office, 445 West Gunnison Ave., Suite 240, Grand Junction, CO 81501; telephone 970-243-2778; facsimile 970-245-6933. If you use a telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD), call the Federal Information Relay Service (FIRS) at 800-877-8339.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. This is a final rule to designate critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse. Under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.) (Act), any species that is determined to be an endangered or threatened species requires critical habitat to be designated, to the maximum extent prudent and determinable. Designations and revisions of critical habitat can only be completed by issuing a rule.

Elsewhere in today's Federal Register, we, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), publish a final rule to list the Gunnison sage-grouse as a threatened species under the Act. On January 11, 2013, we published in the Federal Register a proposed rule to designate critical habitat for the species (78 FR 2540). Section 4(b)(2) of the Act states that the Secretary shall designate critical habitat on the basis of the best available scientific data after taking into consideration the economic impact, national security impact, and any other relevant impact of specifying any particular area as critical habitat.

The critical habitat areas we are designating in this rule constitute our current best assessment of the areas that meet the definition of critical habitat for Gunnison sage-grouse. Here we are designating approximately 1,429,551 acres (ac) (578,515 hectares (ha)) in six units in Delta, Dolores, Gunnison, Hinsdale, Mesa, Montrose, Ouray, Saguache, and San Miguel Counties in Colorado, and in Grand and San Juan Counties in Utah.

This rule consists of: A final rule designating critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse. The Gunnison sage-grouse is concurrently being listed as threatened under the Act, in a separate rule elsewhere in today's Federal Register. This rule designates critical habitat necessary for the conservation of the species.

We have prepared an economic analysis of the designation of critical habitat. In order to consider economic impacts, we prepared an analysis of the economic impacts of the critical habitat designations and related factors. We announced the availability of the draft economic analysis (DEA) in the Federal Register on September 19, 2013 (78 FR 57604), allowing the public to provide comments on our analysis. We have incorporated the comments into our analysis and have completed the final economic analysis (FEA) concurrently with this final determination.

Peer review and public comment. We sought comments on our proposed critical habitat rule (as well as our proposal to list the species) from independent and appropriate specialists to ensure that our designation is based on scientifically sound data and analyses. We obtained opinions from five knowledgeable individuals with relevant scientific expertise to review our technical assumptions, analysis, and whether or not we had used the best available information. One peer reviewer concluded that our proposals included a thorough and accurate review of the available scientific and commercial data on Gunnison sage-grouse, but did not provide substantive comments. The remaining four letters provided additional relevant information on biology, threats, and scientific research for the species. Two peer review letters were generally in opposition to the proposals and questioned our rationale and determinations. Information we received from peer review is considered and incorporated as appropriate in this final revised designation. We also considered all comments and information received from the public during each comment period.

Previous Federal Actions

Please see the proposed (78 FR 2486, January 11, 2013) and final listing rules (published elsewhere in today's Federal Register) for a history of previous Federal actions related to Gunnison sage-grouse prior to January 11, 2013.

On January 11, 2013, we published in the Federal Register a proposed rule to list Gunnison sage-grouse as endangered (78 FR 2486), and a proposed rule to designate critical habitat for the species (78 FR 2540). We proposed to designate as critical habitat approximately 1,704,227 acres (689,675 hectares) in seven units located in Chaffee, Delta, Dolores, Gunnison, Hinsdale, Mesa, Montrose, Ouray, Saguache, and San Miguel Counties in Colorado, and in Grand and San Juan Counties in Utah. Those proposals initially had a 60-day Start Printed Page 69313comment period, ending March 12, 2013, but we extended the comment period by an additional 21 days, through April 2, 2013 (78 FR 15925, March 13, 2013).

On July 19, 2013, we extended the timeline for making final determinations on both proposed rules by 6 months due to scientific disagreement regarding the sufficiency and accuracy of the available data relevant to the proposals, and we reopened the public comment period to seek additional information to clarify the issues in question (78 FR 43123). In accordance with that July 19, 2013, publication, we indicated our intent to submit a final listing determination and a final critical habitat designation for Gunnison sage-grouse to the Federal Register on or before March 31, 2014.

On September 19, 2013, we announced in the Federal Register the availability of the draft economic analysis and a draft environmental assessment prepared pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for the proposed critical habitat designation, and reopened the public comment period until October 19, 2013 (78 FR 57604). The draft economic analysis (IEc 2013, entire) was prepared to identify and evaluate the economic impacts of the proposed critical habitat designation. We also reopened the public comment period from November 4, 2013, through December 2, 2013, and announced the rescheduling of three public hearings on the proposed listing and critical habitat rules due to delays caused by the lapse in government appropriations in October 2013 (78 FR 65936, November 4, 2013). All substantive information received during all public comment periods related to the critical habitat designation, economic analysis, and environmental assessment have been incorporated directly into the final versions of those documents, or addressed below (see Peer Review and Public Comments).

On February 11, 2014, we announced a 6-week extension to May 12, 2014, for our final decision on our proposed listing and critical habitat rules (USFWS 2014e). This extension was granted by the Court due to delays caused by the lapse in government appropriations in October 2013, and the resulting need to reopen a public comment period and reschedule public hearings. On May 6, 2014, we announced a 6-month extension to November 12, 2014, as approved by the Court, to make our final listing and critical habitat decisions (USFWS 2014f).

Summary of Changes From Proposed Rule

- We refined some critical habitat boundaries based the most recent occupied habitat spatial layers by Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW). We also modified the unoccupied habitat in the Sanborn Park/Iron Springs area to better match CPW's mapping. We also deleted one unoccupied polygon (Bostwick Park) in the Cerro Summit area based on the low likelihood of this area supporting birds.

- Although we previously proposed designating a critical habitat unit in Poncha Pass, information received since the publication of the proposed rule has caused us to reevaluate the appropriateness of including the unit. Poncha Pass is thought to have been part of the historical distribution of Gunnison sage-grouse. There were no grouse there, however, when a population was established via transplant from 30 Gunnison Basin birds in 1971 and 1972. In 1992, hunters harvested at least 30 grouse from the population when CPW inadvertently opened the area to hunting. We have no information on the population's trends until 1999 when the population was estimated at roughly 25 birds. In one year, the population declined to less than 5 grouse, when more grouse were brought in, again from the Gunnison Basin, in 2000 and 2001. In 2002, the population rose to just over 40 grouse, but starting in 2006, the population again started declining until no grouse were detected in lek surveys in the spring of 2013 (after publication of the proposed critical habitat rule). Grouse were again brought in in the fall of 2013 and 2014 and six grouse were counted in the Poncha Pass population during the spring 2014 lek count (CPW 2014d, p. 2); however, no subsequent evidence of reproduction was found. We now conclude that the Poncha Pass area, for reasons unknown, is not a landscape capable of supporting a population of Gunnison sage-grouse and therefore does not meet primary constituent element (PCE) 1. As a result, we have determined that the Poncha Pass area should not be designated as critical habitat, and have therefore removed this proposed critical habitat unit from the final critical habitat designation.

- Based on peer review and public comments and our analysis, this final rule excludes specific properties from the critical habitat designation under section 4(b)(2) of the Act, namely private lands enrolled in the Gunnison Sage-grouse Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA) as of the effective date of this rule, private lands under permanent conservation easement (CE) as of August 28, 2013 as identified by Lohr and Gray (2013), and private land owned by the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe under restricted fee status that is subject to a species conservation plan as of the effective date of this final rule (see Exclusions). These private land exclusions reduced the total critical habitat designation from 1,621,008 ac (655,957 ha) to 1,429,551 ac (578,515 ha) (see Table 1).

- We modified the boundaries of this critical habitat designation around the City of Gunnison. We refined the boundary to leave out areas of medium- to high-intensity development, airport runways, and golf courses. In all other areas, lands covered by buildings, pavement, and other manmade structures, as of the effective date of this rule, are not included in this designation, even if they occur inside the boundaries of a critical habitat unit, because such lands lack physical and biological features essential to the conservation of Gunnison sage-grouse, and hence do not constitute critical habitat as defined in section 3(5)(A)(i) of the Act.

- Based on comments and recommendations received by peer reviewers and the public, in this final rule, we refined our description of the PCEs (see Primary Constituent Elements for Gunnison Sage-grouse) and have provided more detailed background and rationale for the criteria and methods used to identify and map critical habitat (see Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat).Start Printed Page 69314

Start Printed Page 69315Table 1—Size and Current Occupancy Status of Gunnison Sage-Grouse in Proposed and Final Designated Critical Habitat Units a

Critical habitat unit Proposed critical habitat Final critical habitat without exclusions Final critical habitat with exclusions Ac Ha Occupied? Ac Ha Ac Ha Occupied? Ac Ha Ac Ha Occupied? Ac Ha Monticello-Dove Creek 348,353 14,097 Yes 111,945 45,303 348,949 141,214 Yes 112,543 45,544 343,000 138,807 Yes 107,061 43,326 No 236,408 95,671 No 236,405 95,670 No 235,940 95,481 Piñon Mesa 245,179 99,220 Yes 38,905 15,744 245,925 99,522 Yes 44,678 18,080 207,792 84,087 Yes 28,820 11,663 No 206,274 83,476 No 201,247 81,442 No 178,972 72,424 San Miguel Basin 165,769 67,084 Yes 101,371 41,023 143,277 57,982 Yes 101,750 41,177 121,929 49,343 Yes 81,514 32,988 No 64,398 26,061 No 41,526 16,805 No 40,414 16,355 Cerro Summit-Cimarron-Sims Mesa 62,708 25,334 Yes 37,161 15,038 56,541 22,881 Yes 37,161 15,039 52,544 21,264 Yes 33,675 13,628 No 25,547 10,339 No 19,380 7,843 No 18,869 7,636 Crawford 97,123 3,930 Yes 35,015 14,170 97,124 39,305 Yes 35,015 14,170 83,671 33,860 Yes 32,632 13,206 No 62,109 25,134 No 62,109 25,134 No 51,039 20,655 Gunnison Basin 76,802 298,173 Yes 592,952 239,959 729,194 295,053 Yes 592,168 239,600 620,616 251,154 Yes 500,909 202,711 No 143,850 58,214 No 137,027 55,453 No 119,707 48,444 Poncha Pass 48,292 19,543 Yes 20,416 8,262 No 27,877 11,281 Not included in the final critical habitat designation All Units 1,704,227 689,675 Yes 937,765 379,499 1,621,008 655,957 Yes 923,314 349,238 1,429,551 578,515 Yes 784,611 317,521 No 766,463 310,176 No 697,694 306,719 No 644,940 260,994 a Numbers may not sum due to rounding. Peer Review and Public Comments

In our January 11, 2013, proposed rules for Gunnison sage-grouse (proposed listing, 78 FR 2486; and proposed critical habitat designation, 78 FR 2540), we requested written public comments on the proposals. We requested written comments from the public on the proposed designation of critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse during four comment periods, spanning from January 11, 2013, to December 2, 2013 (see Previous Federal Actions). We also requested comments on the associated draft economic analysis and environmental assessment during two of those comment periods (see Previous Federal Actions). We contacted appropriate State and Federal agencies, county governments, elected officials, scientific organizations, and other interested parties and invited them to comment. We also published notices inviting general public comment in local newspapers throughout the species' range. From January 11, 2013, to December 2, 2013, we received a total of 36,171 comment letters on both proposals. Of those letters, approximately 445 were substantive comment letters; 35,535 were substantive form letters; and 191 were non-substantive comment letters.

Substantive letters generally contained comments pertinent to both proposed rules, although the vast majority of comments were related to the proposed listing rule. Responses to comments related to the listing rule are provided in the final rule to list Gunnison sage-grouse as threatened, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register. Also, three public hearings were held November 19-21, 2013, in response to requests from local and State agencies and governments; oral comments were received during that time (see Previous Federal Actions). All substantive information related to critical habitat provided during the comment periods has been incorporated directly into this final rule or addressed below. For the readers' convenience, we combined similar comments and responses.

Peer Review

In accordance with our peer review policy published in the Federal Register on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34270), we solicited and received expert opinion from five appropriate and independent individuals with scientific expertise on Gunnison sage-grouse biology and conservation. The purpose of the peer review is to ensure that our decisions are based on scientifically sound data, assumptions, and analyses, based on the input of appropriate experts and specialists. We received written responses from all five peer reviewers. We reviewed all comments received from the peer reviewers for substantive issues and new information regarding critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse. One peer reviewer concluded that our proposals included a thorough and accurate review of the available scientific and commercial data on Gunnison sage-grouse, but did not provide substantive comments. The remaining four letters provided additional relevant information on biology, threats, and scientific research for the species. Two peer review letters were generally in opposition to the proposed listing and critical habitat designation and questioned our rationale and determinations. All substantive comments from peer reviewers related to critical habitat are incorporated directly into this final rule or addressed in the summary of comments below. For the readers' convenience, similar comments and responses are combined.

Comments From Peer Reviewers

(1) Comment: One peer reviewer commented that we should consider including measures of residual grass cover and height in the assessment of breeding habitat within the PCEs for Gunnison sage-grouse critical habitat.

Our response: As described in this final rule, habitat structural values for breeding habitat (PCE 2) are based on the Gunnison Sage-grouse Rangewide Conservation Plan (RCP) and are considered average values over a given project or area (Gunnison Sage-grouse Rangewide Steering Committee (GSRSC) 2005, p. H-6). This comprises the best available information for breeding habitat requirements of Gunnison sage-grouse. The RCP does not specifically define minimum residual grass cover or height (remaining seasonal vegetation following livestock grazing) or grazing management for breeding habitats. However, the PCE 2 includes habitat structural guidelines that require appropriate and cognizant management (i.e., related to livestock grazing and forage utilization levels) to ensure that adequate residual grass cover and height are achieved and maintained. Thus, we conclude that the PCEs indirectly address residual grass cover and height requirements for Gunnison sage-grouse. This topic is discussed further in the Primary Constituent Elements for Gunnison Sage-grouse section of this final rule.

(2) Comment: A peer reviewer stated that the sagebrush canopy cover and height requirements establishing winter habitat seem high, as compared to greater sage-grouse needs, and given that sagebrush exposed above the snow is the overriding consideration for wintering habitat, and this exposure often occurs in wind-blown areas where sagebrush cover and height are much less than the numbers presented here.

Our response: Winter habitat for Gunnison sage-grouse either has sufficient shrub height to be above average snow depths, or is exposed due to topographic features (e.g., windswept ridges, south-facing slopes) (GSRSC 2005, p. H-3). As described in this final rule, habitat structural values for winter habitat (PCE 4) are specific to Gunnison sage-grouse and its habitat and are based on the RCP and studies that quantified vegetation attributes of winter habitat used by Gunnison sage-grouse (Hupp 1987, entire; GSRSC 2005, pp. H-2 to H-3). These are considered average values over a given project or area (GSRSC 2005, p. H-8). This comprises the best available information for the winter habitat requirements specific to Gunnison sage-grouse. This topic is discussed further in the Primary Constituent Elements for Gunnison Sage-grouse section of this final rule.

(3) Comment: A peer reviewer stated that it is not clear in the proposed rule what methods and criteria were used to identify and map critical habitat, or why.

Our response: In this final rule, we expand our description of the criteria and methods used to identify and map critical habitat and provide detailed rationale for our analysis and approach (see Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat).

(4) Comment: A peer reviewer noted that habitat in Utah at brood location sites did not meet the rangewide structural habitat guidelines (and by extension, do not contain the proposed PCEs), yet brood production, based on small samples sizes, exceeded what was previously reported for Colorado (Young 1994, Apa 2004). The peer reviewer suggested that these habitat differences were an artifact of the hens with broods selecting for Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) fields where sagebrush cover was limited to small patches.

Our response: As indicated in the peer reviewer's information, brood production in the subject study area (areas with lower vegetation structural values than identified by the RCP and our PCEs) was based on a very small sample size—the broods of just three hens were monitored during this study (Lupis 2005, p. 28). Therefore, we cannot conclude from this study that brood production of Gunnison sage-grouse in Utah is higher than observed Start Printed Page 69316in Colorado, despite lower habitat structural values in the study area.

As described in this final rule, habitat structural values for breeding habitat (PCE 2) are based on the RCP and are considered average values over a given project or area (GSRSC 2005, p. H-6). This comprises the best available information for breeding habitat requirements of Gunnison sage-grouse. Agricultural fields, which include CRP lands, are also included in both PCE 2 and PCE 3, because the best available science indicates that these lands are sometimes used by the species as early brood-rearing and summer-late fall habitat when they are part of a landscape that otherwise encompasses the species' seasonal habitats. We therefore acknowledge the benefits of CRP lands to Gunnison sage-grouse, as habitat provided under this program is generally more beneficial to the species than lands under more intensive agricultural uses such as crop production. Gunnison sage-grouse are known, for example, to regularly use CRP lands in the Monticello population (Lupis et al. 2006, pp. 959-960; Ward 2007, p. 15). In San Juan County, Gunnison sage-grouse use CRP lands in proportion to their availability (Lupis et al. 2006, p. 959). However, CRP lands are generally lacking in the sagebrush and shrub components typically critical to the survival and reproduction of Gunnison sage-grouse and vary greatly in plant diversity and forb abundance (Lupis et al. 2006, pp. 959-960; Prather 2010, p. 32). As such, while these CRP lands are considered critical habitat, they are generally of lower value or quality than native sagebrush habitats. Future section 7(a)(2) consultations regarding the potential effect of a Federal project on critical habitat would take into consideration the value or quality of the affected habitat.

The CRP program is evaluated in our final rule to list Gunnison sage-grouse as threatened, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register.

(5) Comment: A peer reviewer noted that the total area summarized as unoccupied habitat in Table 4 of the proposed critical habitat rule approximates estimates provided by the Utah Division of Wildlife for Utah based on sagebrush cover. The peer reviewer further noted that unoccupied areas north of Highway 491 in Utah approximate rangewide habitat guidelines. However within this area, approximately 30,000 acres would be considered non-habitat (Table 3, San Juan County Working Group 2000) because they are largely dominated by piñon-juniper (Pinus edulis-Juniperus spp.). Therefore, the peer reviewer suggested that many of the areas included in the critical habitat designation may not contain suitable habitat.

Our response: Unoccupied habitat does not need to contain the PCEs, the standard is instead “essential for the conservation of the species.” For occupied habitat at the landscape scale, we consider all areas designated as occupied critical habitat here to meet the landscape specific PCE (1) and one or more of the seasonally specific PCEs (2-5). Although in our final listing rule, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register, we found that using a 1.5-km radius (window) analysis was not appropriate for evaluating the effects of residential development, for our habitat suitability analysis, we found that, at the 1.5-km radius scale (or window) (based on Aldridge et al. 2012, p. 400), areas where at least 25 percent of the land is dominated by sagebrush cover (based on Wisdom et al. 2011, pp. 465-467; and Aldridge et al. 2008b, pp. 989-990) provided the best estimation of our current knowledge of Gunnison sage-grouse occupied range and suitable habitat. It is important to note that 25 percent of a 1.5-km radius area being dominated by sagebrush cover (as classified by Southwest Regional Gap Analysis Project (SWReGAP) 30 x 30 meter pixels) is very different from an area having 25 percent canopy cover of sagebrush. At the landscape scale, there will still be areas (up to 75 percent) that are not dominated by sagebrush within the larger matrix of Gunnison sage-grouse occupied habitat. For example, there will be areas within this landscape that are dominated by piñon-juniper or mixed shrub communities that will still be occupied critical habitat, because at the landscape scale considered here, these areas are still part of the larger Gunnison sage-grouse habitat. In a critical habitat determination, the Service determines what scale is most meaningful to identifying specific areas that meet the definition of “critical habitat” under the Act. For example, for a wide-ranging, landscape species covering a large area of occupied and potential habitat across several States (such as the Gunnison sage-grouse), a relatively coarse-scale analysis is appropriate and sufficient to designate critical habitat as defined by the Act, while for a narrow endemic species, with specialized habitat requirements and relatively few discrete occurrences, it might be appropriate to engage in a relatively fine-scale analysis for the designation of critical habitat.

(6) Comment: A peer reviewer noted that the answer to “how much is enough” in terms of the minimum size landscape needed to support a sage-grouse population remains uncertain. This peer reviewer felt that the Monticello population area proposed critical habitat should include only the Conservation Study Area (CSA), and that additional areas include some sites dominated by piñon-juniper and deep draws and canyons that may never provide suitable Gunnison sage-grouse habitat. Thus, the peer reviewer recommended refining the proposed critical habitat boundaries to include only the CSA and appropriate buffer areas as defined by Prather (2010).

Our response: The Act directs us to designate critical habitat in areas outside the geographic area occupied by the species at the time it is listed (such as the CSA), upon a determination that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. For the Gunnison sage-grouse, we evaluated the ability of unoccupied habitat to potentially provide for the landscape scale habitat needs of the species by identifying areas of large size with large areas dominated by sagebrush. A minimum of 500 birds may be necessary to support a viable population (Shaffer 1981, p. 133; GSRSC 2005, pp. 2 and 170). Approximately 100,000 ac (40,500 ha) likely would be needed to support 500 birds (GSRSC 2005, p. 197). Currently occupied habitat is less than this amount for three of the six Gunnison sage-grouse populations included in this final designation--Piñon Mesa, Cerro Summit-Cimarron-Sims Mesa, and Crawford. Two other populations—Monticello-Dove Creek and San Miguel Basin--slightly exceeds this amount. This suggests that currently occupied habitat alone may not be sufficient to maintain long-term viability for at least three and possibly five of the six populations included in this final designation. Declining trends in the abundance of Gunnison sage-grouse outside of the Gunnison Basin further indicate that currently occupied habitat for the five satellite populations included in this final designation may be less than the minimum amount of habitat necessary for their long-term viability. Therefore, we consider the designation of unoccupied critical habitat, including areas outside the CSA in the Monticello population area, essential for conservation of the species.

As we discuss in detail below, our delineation of unoccupied critical habitat areas was based on specific criteria, scientific data, and mapping methods on a landscape scale. These parameters were consistently applied across the range of Gunnison sage-grouse to ensure the integrity and reliability of the maps on a broad scale, Start Printed Page 69317as opposed to applying varying sources and scales of data or information on habitat conditions. This topic is discussed further under Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat in this final rule.

In a critical habitat determination, the Service determines what scale is most meaningful to identifying specific areas that meet the definition of “critical habitat” under the Act. For example, for a wide-ranging, landscape species covering a large area of occupied and potential habitat across several States (such as the Gunnison sage-grouse), a relatively coarse-scale analysis is appropriate and sufficient to designate critical habitat as defined by the Act. While for a narrow endemic species, with specialized habitat requirements and relatively few discrete occurrences, it might be appropriate to engage in a relatively fine-scale analysis for the designation of critical habitat.

Comments From States

Comments received from the States regarding the proposal to designate critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse are incorporated directly into this final rule or are addressed below.

(1) Comment: Arizona Game and Fish Department stated that any designation of Gunnison sage-grouse critical habitat should occur within the current distribution for the species, in Colorado and Utah.

Our Response: Critical habitat has been designated only in Colorado and Utah, within the current range of the species.

(2) Comment: Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) requested justification for our use of the Dolores County line as the southern boundary for critical habitat designation, and not including areas of habitat within Montezuma County.

Our Response: Our identification of lands that contain the features essential to conservation of the Gunnison sage-grouse was based on a habitat mapping project by the Gunnison Sage-grouse Rangewide Steering Committee in 2005 (78 FR 2547, January 11, 2013). The Gunnison Sage-grouse Rangewide Conservation Plan notes that the local conservation plan for Dove Creek was limited to Dolores County (GSRSC 2005, p. 70). The RCP potential habitat polygon that extended into Montezuma County was very large. The portion of the potential polygon that fell within Montezuma County had little suitable habitat (less than 20 percent of the almost 95,000 ac) and the suitable habitat was almost all more than 18.5 km away from occupied habitat. The Dove Creek Conservation Plan (1998, p. 7) states that the species is not known to currently occur in Montezuma County. Further, vegetation data indicate that areas in Montezuma County are generally unsuitable for the species. For these reasons, we modified this very large potential polygon so it no longer included Montezuma County. Criteria for identifying and mapping critical habitat are described in further detail in this final rule (see Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat).

(3) Comment: CPW and one other commenter questioned the use of 18 kilometers (km) (11 miles (mi)) as a distance for seasonal movement and for critical habitat designation. CPW stated that this distance is for extreme movements and results in large areas of non-habitat being included in the critical habitat designation.

Our Response: Gunnison sage-grouse make relatively large movements on an annual basis (GSRSC 2005, p. J-3). The movement distances of Gunnison sage-grouse as a criterion for identifying unoccupied critical habitat areas are discussed in this final rule (see Proximity and Potential Connectivity (Criterion 3)). To account for proximity to and potential connectivity with occupied Gunnison sage-grouse habitat, we only considered unoccupied areas meeting our other criteria to be critical habitat if they occur within approximately 18.5 km (11.5 mi) of occupied habitat (using “shortest distance”). This distance represents the rangewide maximum measured seasonal movement of Gunnison sage-grouse across all seasons, as presented in the RCP (GSRSC 2005, p. J-3). Therefore, outside of occupied habitat, we conclude that unoccupied areas within 18.5 km (11.5 mi) of occupied areas have the highest likelihood of Gunnison sage-grouse use and occupation.

Other scientific information further supports our use of 18.5 km to account for habitat connectivity. Connelly et al. (2000a, p. 978) recommended protection of breeding habitats within 18 km of active leks in migratory sage-grouse populations. The maximum dispersal distance of greater sage-grouse in northwestern Colorado was greater than 20.0 km (12.4 mi) and, therefore, it was suggested that populations within this distance could maintain gene flow and connectivity (Thompson 2012, pp. 285-286). It was hypothesized that isolated patches of suitable habitats within 18 km (11.2 mi) provide for connectivity between sage-grouse populations; however, information on how sage-grouse actually move through landscapes is lacking (Knick and Hanser 2011, pp. 402, 404).

We recognize that Gunnison sage-grouse movement behavior and distances likely vary widely by population and area, potentially as a function of population dynamics, limited or degraded habitats, and similar factors. Movements have been documented as being much greater (up to 56 km (35 mi)) or less than 18.5 km in some cases (see our final rule to list Gunnison sage-grouse elsewhere in today's Federal Register for more discussion). However, the best available information indicates 18.5 km is a reasonable estimate of the distance required between habitats and populations to ensure connectivity for Gunnison sage-grouse, or facilitate future expansion of the species range—hence, we used this measure in our evaluation of areas as potential critical habitat. This topic is discussed further under Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat in this final rule.

(4) Comment: CPW recommended that the following areas of proposed critical habitat be reevaluated: Pine forests along the eastern boundary of Gunnison Basin, Sanborn Park north of Iron Springs, Bostwick Park and Poverty Mesa in the Cerro Summit-Cimarron-Sims Mesa Unit, Black Mesa between Crawford and Gunnison Basin (they requested that we exclude the north side and include the south side), southern Dove Creek, Hinsdale County, and the southeastern portion of Sims Mesa. CPW recommended that these areas be reevaluated for a variety of reasons, including updated mapping, severely degraded or converted habitats, and inappropriate habitats (such as forested areas).

Our Response: We have modified our critical habitat designation to address several of CPWs concerns as follows: (1) We modified several occupied polygons to reflect the latest mapping from CPW (CPW 2013e, spatial data); (2) we used CPW's mapping for unoccupied habitat in the Sanborn Park/Iron Springs area; and (3) we removed the unoccupied habitat in the Bostwick Park area (part of the Cerro Summit-Cimarron-Sims Mesa population) from our critical habitat designation because the habitat has been converted to a point where restoration to Gunnison age-grouse habitat would be highly unlikely and because it did not meet our suitability criterion (see Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat below). Other areas have remained the same based on our sagebrush habitat suitability analysis as further described here.

For occupied habitat, we based our identification of lands that contain the Start Printed Page 69318PCEs for Gunnison sage-grouse on polygons delineated, defined, and updated by Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (UDWR) as part of the 2005 RCP Habitat Mapping project (GSRSC 2005, p. 54; CPW 2013e, spatial data). We consider all areas designated as occupied critical habitat here to meet the landscape specific PCE 1 and one or more of the seasonally specific PCEs (2-5). In general, for PCE 1, this includes areas with vegetation composed of sagebrush plant communities (at least 25 percent of the land is dominated by sagebrush within a 0.9-mi (1.5-km) radius of any given location) (see Habitat Suitability), of sufficient size and configuration to encompass all seasonal habitats for a given population of Gunnison sage-grouse, and facilitate movements within and among populations.

We based our identification of unoccupied critical habitat for Gunnison sage-grouse on four criteria: (1) The overall distribution or range of the species; (2) potential occupancy of the species; (3) proximity and potential connectivity to occupied habitats; and (4) suitability of the habitat for the species. Our delineation of unoccupied critical habitat areas was based on these criteria, scientific data, and mapping methods on a landscape scale. These parameters were consistently applied across the range of Gunnison sage-grouse to ensure the integrity and reliability of the maps on a broad scale, as opposed to applying varying sources and scales of data or information on habitat conditions.

In this designation, as described in Criteria and Methods Used to identify and map Critical Habitat, we utilized the best available information to identify areas for critical habitat at a landscape level scale. At a smaller scale, there are local areas that do not meet these landscape criteria, and for occupied habitat, the PCEs. All occupied areas have the PCEs on a landscape scale, and unoccupied areas meet the landscape criteria at a landscape scale as well, therefore these areas are designated as critical habitat.

Gunnison and greater sage-grouse occupancy, survival, and persistence are dependent on the availability of sufficient sagebrush habitat on a landscape scale (Patterson 1952, p. 9; Braun 1987, p. 1; Schroeder et al. 2004, p. 364; Knick and Connelly 2011, entire; Aldridge et al. 2012, entire; Wisdom et al. 2011, entire). Aldridge et al. (2008b, pp. 989-990) reported that at least 25 percent of the land needed to be dominated by sagebrush cover within a 30 km (18.6 mi) radius scale for long-term persistence of sage-grouse populations. Wisdom et al. (2011, pp. 465-467) indicated that at least 27 percent of the land needed to be dominated by sagebrush cover within an 18-km (11.2-mi) radius scale for a higher probability of sage-grouse population persistence. Although in our final listing rule, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register, we found that using a 1.5-km radius (window) analysis was not appropriate for evaluating the effects of residential development, for our habitat suitability analysis, we found that, at the 1.5-km radius scale (or window) (based on Aldridge et al. 2012, p. 400), areas where at least 25 percent of the land is dominated by sagebrush cover (based on Wisdom et al. 2011, pp. 465-467; and Aldridge et al. 2008, pp. 989-990) provided the best estimation of our current knowledge of Gunnison sage-grouse occupied range and suitable habitat. It is important to note that 25 percent of a 1.5-km radius area being dominated by sagebrush cover (as classified by SWReGAP 30 x 30 meter pixels) is very different from an area having 25 percent canopy cover of sagebrush. At the landscape scale, there will still be areas (up to 75 percent) that are not dominated by sagebrush within the larger matrix of Gunnison sage-grouse occupied habitat. For example, there are areas within this landscape that are dominated by piñon-juniper or mixed shrub communities that are still occupied critical habitat, because at the landscape scale considered here, these areas are still part of the larger Gunnison sage-grouse habitat. In a critical habitat determination, the Service determines what scale is most meaningful to identifying specific areas that meet the definition of “critical habitat” under the Act. For example, for a wide-ranging, landscape species covering a large area of occupied and potential habitat across several States (such as the Gunnison sage-grouse), a relatively coarse-scale analysis is appropriate and sufficient to designate critical habitat as defined by the Act. While for a narrow endemic species, with specialized habitat requirements and relatively few discrete occurrences, it might be appropriate to engage in a relatively fine-scale analysis for the designation of critical habitat.

Although in our final listing rule, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register, we found that using a 1.5-km radius (window) analysis was not appropriate for evaluating the effects of residential development, we found that, at the 1.5-km radius scale (or window) (based on Aldridge et al. 2012, p. 400), mapping areas where at least 25 percent of the land is dominated by sagebrush cover (based on Wisdom et al. 2011, pp. 465-467; and Aldridge et al. 2008, pp. 989-990) provided the best estimation of our current knowledge of Gunnison sage-grouse occupied range and suitable habitat. Specifically, we found that modeling at the finer 1.5-km scale was necessary to identify or “capture” all areas of known occupied range, particularly in the smaller satellite populations where sagebrush habitat is generally limited in extent. Larger scales failed to capture areas that we know to contain occupied and suitable habitats (e.g., at the 54-km scale, only the Gunnison Basin area contained areas where 25 percent or more of the land is dominated by sagebrush cover) (USFWS 2013d, p. 3).

The scale of the maps provided in the final rule to designate critical habitat does not allow for delineation of some developed areas such as buildings, paved areas, and other manmade structures within critical habitat that do not contain the required PCEs; nonetheless, lands covered by buildings, pavement and other manmade structures on the effective date of this rule are not included in critical habitat, and text has been included in the final regulation to make this point clear. This topic is discussed further under Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat in this final rule.

(5) Comment: The Colorado Department of Agriculture, the State of Utah Office of the Governor, and several other commenters expressed concern that critical habitat designation would impact the local economy, with income losses due to restrictions to agriculture, energy development, mineral extraction, or hunting.

Our Response: We expect some economic impacts as a result of designating critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse. The Final Economic Analysis (FEA) forecasted incremental impacts from the critical habitat designation alone (not including baseline impacts due to listing of the species) of $6.9 million (present value over 20 years), assuming a seven percent discount rate. Assuming a social rate of time preference of three percent, incremental impacts were $8.8 million (present value over 20 years). Annualized incremental impacts of the critical habitat designation were forecast to be $610,000 at a seven percent discount rate, or $580,000 at a three percent discount rate (Industrial Economics, Inc. 2014, p. ES-2). Estimated economic impacts for a 20-year period regarding livestock grazing, agriculture and water management, mineral and fossil fuel extraction, Start Printed Page 69319residential development, renewable energy development, recreation, and transportation are described in the FEA (Industrial Economics, Inc. 2014). Actions carried out, authorized by or funded by a Federal agency that might affect the species or its critical habitat would require section 7 consultations under the Act.

(6) Comment: The State of Utah Office of the Governor asserted that voluntary cooperation of private landowners will be much more effective in improving habitat for Gunnison sage-grouse than protections afforded by listing and designation of critical habitat.

Our Response: We agree that voluntary cooperation of private landowners will be key in improving habitat for Gunnison sage-grouse. However, under the Act, we must list a species that meets the definition of a threatened or endangered species, and we have determined that the Gunnison sage-grouse meets this definition. We believe that the best opportunity to conserve and ultimately recover the species will require both the protections afforded by listing and the critical habitat designation as well as voluntary conservation measures undertaken by private landowners, with support from the State in accomplishing these measures.

(7) Comment: The State of Utah Office of the Governor asserted that the critical habitat designation for Utah is too broad and erroneously includes sagebrush (Artemisia spp.) areas that likely never supported Gunnison sage-grouse, but are based on habitat definitions from the Gunnison Sage-grouse Rangewide Conservation Plan. Similarly, a Federal agency asserted that approximately one-third of unoccupied habitat proposed for designation as critical habitat does not contain at least 25 percent sagebrush cover and suggested that we clearly identify the criteria (such as soil type) that indicate sagebrush communities once occurred.

Our Response: See our responses to comments 3 and 4 above, which explain the methodology we used to delineate critical habitat areas.

(8) Comment: CPW commented that, within proposed unoccupied critical habitat, mapped “vacant/unknown habitat” should be considered more important than “potentially suitable habitat” because restoration would not be required in vacant/unknown habitat. Additionally, CPW recommended that old-growth piñon-juniper, exurban lands, and agricultural lands be removed from the category of potentially suitable habitat.

Our Response: We consider both categories of unoccupied critical habitat (vacant/unknown and potentially suitable habitat, as defined by the RCP) to be essential to conservation of the Gunnison sage-grouse. However, habitat conditions and suitability across these areas vary, and we recognize that certain areas may require restoration to meet the needs of Gunnison sage-grouse. With respect to exurban lands, lands covered by buildings, pavement and other manmade structures on the effective date of this rule are not included in this critical habitat designation, either by mapping or by text in this final rule. With respect to unoccupied agricultural lands, these areas can be important for various seasonal uses by grouse and can, because of scale, meet the landscape level habitat suitability criteria. These topics are discussed further under the Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat section in this final rule.

Comments From Federal Agencies

Comments received from Federal agencies regarding the proposal to designate critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse are incorporated directly into this final rule or are addressed below.

(9) Comment: Two Federal agencies noted that the proposed rule to designate critical habitat included areas outside of currently occupied habitat that are deemed essential for the conservation of the Gunnison sage-grouse and questioned how a section 7 adverse modification analysis will be conducted in unoccupied critical habitat that does not contain the PCEs.

Our Response: Our memorandum of December 9, 2004, provides our most current guidance on critical habitat and adverse modification (USFWS 2004). This memorandum describes an analytical framework for adverse modification determinations addressing how critical habitat will be addressed in different sections of the Section 7(a)(2) consultation or Section 7(a)(4) conference. Unoccupied habitat does not need to have the PCEs, the standard is instead “essential to the conservation of the species.” Instead of considering the PCEs, in the section 7 consultation addressing unoccupied habitat, we would expect a discussion of whether critical habitat, through the implementation of the proposed Federal action, would remain functional (or retain the current ability for the PCEs to be functionally established) to serve the intended conservation role for the species (USFWS 2004, p. 3).

We also note that the Service has proposed to amend the definition of “destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat” to (1) more explicitly tie the definition to the stated purpose of the Act; and (2) more clearly contrast the definitions of “destruction or adverse modification” of critical habitat and “jeopardize the continued existence of” any listed species (79FR 27060).

(10) Comment: A Federal agency recommended that critical habitat boundaries and edges should be made contiguous at the Utah and Colorado state line for the Piñon Mesa population and for the Monticello-Dove Creek population.

Our Response: We based our identification of occupied and unoccupied habitats for Gunnison sage-grouse on maps and polygons delineated and defined by the CPW and UDWR. Habitat maps were completed by the CPW and UDWR in support of the 2005 RCP (GSRSC 2005, pp. 54-102) and are updated periodically (CPW 2013e, spatial data). The habitat maps were derived from a combination of telemetry locations, sightings of sage-grouse or sage-grouse sign, local biological expertise, GIS analysis, and other data sources (GSRSC 2005, p. 54; CDOW 2009e, p. 1). These sources, as compiled in the RCP and updated, combined with recent lek count data, collectively constitute the best available information on the species' current distribution and occupancy in Colorado and Utah. In general, we considered areas classified as “occupied habitat” (GSRSC 2005, pp. 38, 54) to be currently occupied by Gunnison sage-grouse. All RCP mapped occupied habitat for Gunnison sage-grouse, except Poncha Pass (which does not meet PCE 1), is included in this critical habitat designation. Unoccupied habitat is included in this designation only when designated by the RCP (including both potential and vacant/unknown habitats), where potential connectivity to occupied habitat exists, and where vegetation cover provides suitable habitat, as described below. This topic is discussed further under the Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat section in this final rule.

According to the RCP information, in the Piñon Mesa population area in Utah, the center polygon is of vacant or unknown status; and the northern and southern polygons are potential habitat. As pointed out, the polygons do not match between Colorado and Utah. For instance, mapped occupied habitat in Colorado terminates at the State line, although adjacent habitat in Utah is shown as unoccupied. In that case, while Gunnison sage-grouse from the Piñon Mesa population are known to seasonally use adjacent habitat in Utah, the area was not classified as occupied Start Printed Page 69320by the RCP (GSRSC 2005, p. 86). In the Monticello-Dove Creek population, part of the state line transition is due to a change to cropland on the Utah side of the border (GSRSC 2005, p. 38). The RCP has identified resolving these mapping issues as an objective, but this resolution has not been completed to date (GSRSC 2005, p. 221). A Federal agency recently suggested that all critical habitat near Monticello, Utah should be considered occupied. This change in designation has not been vetted through the RCP process, which we have determined provides the best available science regarding habitat occupied by the species. Critical habitat designations can also be revised by a future rulemaking, if appropriate. In the meantime, section 7 consultations can incorporate updated information in the analysis of designated critical habitats.

(11) Comment: A Federal agency stated that the following information from statements in the proposed rule to designate critical habitat conflict and need clarification. The first statement was that critical habitat designated at a particular point in time may not include all of the habitat areas that we may later determine are necessary for the recovery of the species. The second statement was that critical habitat units are depicted for Grand and San Juan Counties, Utah, and Chaffee, Delta, Dolores, Gunnison, Hinsdale, Mesa, Montrose, Ouray, Saguache, and San Miguel Counties, Colorado (78 FR 2542 and 2562, January 11, 2013).

Our Response: The first statement acknowledges that with new information we may in the future identify other areas outside of designated critical habitat that are needed for recovery of the species. Consequently, conservation actions for the species can occur outside of critical habitat, section 7 consultations can occur outside of critical habitat if the species is present, and section 9 prohibitions regarding take apply anywhere. The second statement proposes critical habitat, based on the best available information, in portions of the aforementioned counties (note, however, that lands in Chaffee County are no longer included in this final designation). This results in requirements for section 7 consultations within critical habitat, even if the habitat is not currently occupied by the species.

(12) Comment: Several agencies requested that research be cited regarding the justification for the landscape specific PCE 1, and more specifically the generally corresponding habitat suitability analysis (areas with vegetation composed primarily of sagebrush plant communities [at least 25 percent of the area is dominated by sagebrush cover within a 1.5-km (0.9-mi) radius of any given location], of sufficient size and configuration to encompass all seasonal habitats for a given population of Gunnison sage-grouse, and facilitate movements within and among populations). The commenters noted that no on-the-ground assessment was completed to verify the choice of 1.5 km (0.9 mi) as a tool to delineate critical habitat.

Our Response: See our response to comment 4 above. The Act does not require us to collect additional information or do assessments on the ground; instead it requires us to base our decisions on the best available information.

(13) Comment: A Federal agency requested clarification regarding whether each PCE must be met for designation as critical habitat.

Our Response: We consider all areas designated as occupied critical habitat here to meet the landscape specific PCE 1 and one or more of the seasonally specific PCEs (2-5). This topic is discussed under the Primary Constituent Elements for Gunnison Sage-grouse section of this final rule. However, see our response to comment 9 above for a discussion of unoccupied critical habitat and section 7 consultation. Unoccupied critical habitat does not need to contain the PCEs, but rather is designated because it is considered essential to the conservation of the species.

(14) Comment: A Federal agency requested clarification regarding the “non-sagebrush canopy cover component” of PCEs 2-3, and asked whether this component includes trees or just non-sagebrush shrubs.

Our Response: Habitat structural values for the seasonally specific PCEs 2 and 3 (breeding habitat and summer-fall habitat, respectively) are based on the RCP (GSRSC 2005, pp. H-6 and H-7). The non-sagebrush canopy cover component (5 to 15 percent) does not include tree canopy cover, but may include other shrub species such as horsebrush (Tetradymia spp.), rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus spp.), bitterbrush (Purshia spp.), snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), greasewood (Sarcobatus spp.), winterfat (Eurotia lanata), Gambel's oak (Quercus gambelii), snowberry (Symphoricarpos oreophilus), serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), and chokecherry (Prunus virginiana). We clarify this in the Seasonally Specific Primary Constituent Elements section of this final rule.

(15) Comment: A Federal agency suggested that wording in the proposed rule to designate critical habitat (78 FR 2547, January 11, 2013) be changed from implying that wildfire suppression would be a new management consideration to noting that it is an ongoing management action. The agency also requested that the North Rim Landscape Strategy be explicitly recognized as an ongoing conservation effort.

Our Response: In this final rule, we provide a list of management considerations or protections (including wildfire suppression) that may be applied in the future within critical habitat, each of which has been implemented to some extent in the past. We clarify this in the Special Management Considerations section of this final rule. The North Rim Landscape Strategy is discussed in the final rule to list Gunnison sage-grouse as threatened, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register. To the extent the commenter is inquiring about whether certain activities might be “actions” under section 7 of the ESA, this determination is made on a case-by-case basis as an agency investigates whether a particular action is subject to consultation.

(16) Comment: A Federal agency recommended that results from the ESRI “Neighborhood Analysis” tool be provided within the final rule to designate critical habitat.

Our Response: The full results of our modeling and analysis, including the ESRI “Neighborhood Analysis”, are not in a format that can be provided in the Federal Register. However, the data and methods used to perform our analyses are described in greater detail in this final rule (see Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat); and background and supporting data are available by appointment, during normal business hours at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Western Colorado Field Office (see ADDRESSES).

(17) Comment: A Federal agency stated that the proposed rule to designate critical habitat and the proposed rule to list present conflicting viewpoints regarding whether or not fire regimes are altered and whether or not altered fire regimes are a threat.

Our Response: In the proposed and final critical habitat rules for Gunnison sage-grouse, we identified “threats to the physical and biological features” of critical habitat units, including altered fire regimes. These are stressors potentially affecting the conservation and management of critical habitat. This is in contrast to identified threats to the species' continued persistence, as evaluated in the final rule to list Start Printed Page 69321Gunnison sage-grouse (published elsewhere in today's Federal Register). In this final rule, we clarify this point by identifying these stressors as “factors potentially affecting the physical and biological features” of given critical habitat units (see Unit Descriptions).

(18) Comment: A Federal agency recommended adding areas to the critical habitat unit proposed for Piñon Mesa, provided GIS data, and noted that more information is available.

Our Response: We have added and expanded occupied areas in the Piñon Mesa critical habitat unit based on updated mapping provided by CPW. CPW does recognize that the boundaries of Piñon Mesa need to be changed, but those changes were not completed prior to the publication of this rule. CPW modifies their unit boundaries in a group setting with input from numerous individuals and sources. Since a group (that would include the Federal agency) has not been convened by CPW to officially change the Piñon Mesa boundaries, we choose here to rely on the older information provided by CPW as the best currently available information.

(19) Comment: A Federal agency noted that in the proposed rule to designate critical habitat, the text describes “potential” and “vacant or unknown” habitat categories, whereas the maps refer to “occupied” and “unoccupied” habitat.

Our Response: We used RCP “occupied habitat” to define areas currently occupied by Gunnison sage-grouse (GSRSC 2005, pp. 38, 54) (see Criteria and Methods Used to Identify and Map Critical Habitat). We also use the RCP mapped “potential” and “vacant or unknown” habitat polygons (GSRSC 2005, pp. 54-102) to evaluate unoccupied areas as potential critical habitat for Gunnison sage-grouse. We combined and classified these two types as unoccupied habitat for consideration in our analysis and identification of critical habitat (see Potential Occupancy of the Species).

(20) Comment: A Federal agency recommended deleting a portion of unoccupied habitat in the southern part of Gunnison Basin that is forested, and provided shapefiles.

Our Response: We did look at the shapefiles provided. In general, we have relied on the most recent habitat mapping done by CPW (GSRSC 2005, spatial data; CPW 2013e, spatial data) as the best available data. Some critical habitat unit boundaries have been refined based on the mapping by CPW. Our habitat suitability analysis looked at areas that generally correlated with PCE 1 where the dominant species is sagebrush 25 percent of the time within a 1.5 km radius. Given this, there could be up to 75 percent of the time where a different species, such as treed areas, is dominant. See our responses to comments 3 and 4 above.

(21) A Federal agency stated it does not support inclusion of isolated Federal lands polygons of unoccupied habitat within a matrix of private lands that are also unoccupied, unless the Service can demonstrate that those Federal land polygons--if restoration were applied and successful--are valuable in and of themselves for sage-grouse habitat.

Our Response: Unoccupied lands are designated here because they are “essential for the conservation of the species” and these areas do not stop at land ownership boundaries. We recognize that in areas with a high proportion of private ownership and with more intensive land uses (such as agriculture), the conservation of these populations will be more difficult than in less developed areas. In these developed areas, the importance of Federal lands can be greater than less developed areas because there may be fewer conservation options available on private lands (especially those that are already developed). The conservation of the grouse in these more developed areas will be more likely with the cooperation of private landowners and there are numerous tools available to private landowners to work on conservation of the grouse. The comment to exclude Federal lands assumes that restoration is not possible on these private lands.

Our landscape level approach used in this critical habitat designation generally does not consider land ownership. With the exception of exemptions for economic reasons or for Department of Defense lands and exclusions under section 4(b)(2) of the Act (where the benefits of such exclusions outweigh the benefits of inclusion), all lands that contain the PCEs (for occupied areas) or are essential to the conservation of the species (for unoccupied areas) are included in a critical habitat designation. On Federal lands where agencies are required to conserve endangered species (section 7(a)(1) of the Act) and consult on projects that may adversely affect species (section 7(a)(2) of the Act), it is difficult to show how an exclusion outweighs inclusion. In contrast, on private lands where conservation is largely voluntary, rewarding landowners for their conservation efforts by excluding their lands in a critical habitat designation can outweigh the benefits of including those lands.

(22) Comment: The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) recommended several additions and deletions to critical habitat on USFS lands at Crawford, Gunnison Basin, Piñon Mesa, and San Miguel Basin, with a net reduction of 12,781 ha (31,557 ac), and noted the following information:

- Most of the areas proposed for removal at Crawford are forested areas directly north of Blue Mesa Reservoir.

- Waunita Park in Gunnison Basin was considered unoccupied critical habitat in the proposed rule, but Gunnison sage-grouse have been observed in that area by USFS personnel for at least the past 20 years.

- Forested areas in Gunnison Basin should be deleted.

- At Piñon Mesa, sagebrush areas in portions of the Dominguez Creek watershed and in portions of Calamity Basin should be added.

- Forested areas at San Miguel Basin should be removed from critical habitat designation.

Our Response: Waunita Park was changed to occupied habitat, consistent with CPWs updates (CPW 2013e, spatial data). Although in our final listing rule, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register, we found that using a 1.5-km radius (window) analysis was not appropriate for evaluating the effects of residential development, for our habitat suitability analysis, we found that, at the 1.5-km radius scale (or window) (based on Aldridge et al. 2012, p. 400), areas where at least 25 percent of the land is dominated by sagebrush cover (based on Wisdom et al. 2011, pp. 465-467; and Aldridge et al. 2008, pp. 989-990) provided the best estimation of our current knowledge of Gunnison sage-grouse occupied range and suitable habitat. Given this, there could be up to 75 percent of the time where a different vegetation type is dominant, such as treed areas. CPW does recognize that changes are needed to the boundaries of Piñon Mesa, but those changes were not completed by CPW prior to the publication of this rule. CPW modifies their unit boundaries in a group setting with input from numerous individuals and sources. Since a group (that would include the USFS) has not been convened by CPW to change the Piñon Mesa boundaries, we choose here to rely on the older information provided by CPW as the best currently available information. See our responses to comments 3, 4, 18, and 20 above.

(23) Comment: The USFS provided a list of grazing allotments containing critical habitat, dates of permit renewal for those allotments, and information on Start Printed Page 69322whether or not they are covered by the Gunnison Basin Candidate Conservation Agreement (CCA).

Our Response: We considered this information for the final critical habitat (and listing) rules.

(24) Comment: The USFS asked if the proposed designation of critical habitat at the Dolores and Montezuma County line was intended to include any portion of Montezuma County; a close inspection of the map in the proposed rule indicates that a small portion of Montezuma County is included.

Our Response: Montezuma County is not included in this critical habitat designation. Please see our response to comment 2 above; and the map for Critical Habitat Unit 1: Monticello-Dove Creek, at the end of this rule. Any observed overlap of this critical habitat unit with Montezuma County may be due to GIS application and/or projection errors.

(25) Comment: We received several comments about our proposed critical habitat designation at Poncha Pass. One Federal agency recommended revising the delineation of critical habitat at Poncha Pass based on the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Level III Soil classification survey and vegetation potential and provided GIS files. A Federal agency also asserted that most of the unoccupied habitat and a small section of occupied habitat do not have the potential to support sagebrush due to alkaline soils and low precipitation, or do not have the potential to support brood-rearing habitat because of minimal water availability. The USFS recommended that any land in the Rio Grande National Forest on the east side of the Valley at Poncha Pass that is designated as critical habitat be considered unoccupied due to a lack of documented presence. The agency noted that small parcels of USFS land on the west side of the Valley within critical habitat contain sagebrush that might eventually be used by Gunnison sage-grouse. The USFS stated that proposed critical habitat extends too far up the slopes of the Sangre de Cristo Range into mixed-conifer forests and offered to work with the Service in defining critical habitat on the east side of the Valley.

Our Response: Although we previously proposed designating a critical habitat unit in Poncha Pass, information received since the publication of the proposed rule (CPW 2013e, p. 1; CPW 2014d, p. 2; CPW 2014e, p. 2; CPW 2014f, p. 2) has caused us to reevaluate this proposal and to determine that it should not be included in this designation. See Reasons for Removing Poncha Pass as a Critical Habitat Unit below.

Comments From the Public

Comments received from the general public including local governments, organizations, associations, and individuals regarding the proposal to designate critical habitat for the Gunnison sage-grouse are incorporated directly into this final rule or are addressed below.

(26) Comment: Several commenters indicated that National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and economic analyses should be completed and made available for review prior to designating critical habitat.

Our Response: Both a Draft Environmental Assessment, as required by NEPA, and a Draft Economic Analysis were completed and made available for public review on September 19, 2013 (78 FR 57604), prior to this final designation of critical habitat. Comments have been addressed for both the Environmental Assessment and Economic Analysis, and final versions of these documents have been completed and posted to the Service's Web site at http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/birds/gunnisonsagegrouse/ and at http://www.regulations.gov.

(27) Comment: Several commenters expressed differing opinions on whether private lands should be excluded from critical habitat designation.

Our Response: Private lands are essential to the conservation of the species and, therefore, qualify as critical habitat. Federal agencies manage 55 percent of critical habitat designated in this rule. Approximately 43 percent of critical habitat is on private lands. Although there are public lands within the current range of the Gunnison sage-grouse, they are not sufficient to ensure conservation of the species for the reasons discussed in Rationale and Other Considerations below. The language of the Act does not restrict the designation of critical habitat to specific land ownerships such as Federal lands. Consequently, lands of all ownerships are considered if they meet the definition of critical habitat. Designation of private or other non-Federal lands as critical habitat has no regulatory impact on the use of that land unless there is Federal action that is subject to consultation. Identifying non-Federal lands that are essential to the conservation of a species alerts State and local government agencies and private landowners to the value of habitat on their lands, and may promote conservation partnerships. We have, however, excluded from our critical habitat designation 191,460 ac (77,481 ha) of private land where the CCAA, CEs, and a Tribal land management plan provide protection for Gunnison sage-grouse (see Exclusions below).

(28) Comment: Several commenters stated that agricultural lands and other habitat without sagebrush should be excluded from critical habitat designation.

Our Response: The best available information supports the consideration and inclusion of certain agricultural lands and other lands without sagebrush in this critical habitat designation. The PCEs for this species include those habitat components essential for meeting the biological needs of reproducing, rearing of young, foraging, sheltering, dispersing, and exchanging genetic material. Gunnison sage-grouse are sagebrush obligates, requiring large, interconnected expanses of sagebrush plant communities that contain a healthy understory of native, herbaceous vegetation. The species may also use riparian habitat, agricultural lands, and grasslands that are in close proximity to sagebrush habitat. Primary constituent elements 2, 3, and 5 include agricultural lands, and PCE 5 (alternative, mesic habitats) also includes wet meadows, and other habitats that may not contain sagebrush but which occur near sagebrush communities. This topic is discussed further under the Seasonally Specific Primary Constituent Elements section of this final rule.

(29) Comment: Several commenters stated that critical habitat should not include unoccupied habitat.

Our Response: The Service has found that areas outside the geographical area currently occupied by the species are essential for the conservation of the species. Data indicate that the currently occupied habitat area for four populations in this designation is insufficient for the conservation of the species, and may be minimally adequate for one other population (see our response to peer review comment 6). Declining trends in the abundance of Gunnison sage-grouse outside of the Gunnison Basin further indicate that currently occupied habitat for the five satellite populations included in this final designation may be less than the minimum amount of habitat necessary for the conservation of the species. Unoccupied habitat in the Gunnison Basin population is also needed for movement and migration of birds to outlying areas and satellite populations and for potential range expansion. Consequently, we do not believe that occupied habitat alone is sufficient to ensure conservation of the species. We Start Printed Page 69323designated occupied and unoccupied habitat that is essential for conservation of Gunnison sage-grouse. This topic is discussed further under the Rationale and Other Considerations section in this final rule.

(30) Comment: Several commenters stated that critical habitat should include all PCEs throughout the designated area.

Our Response: We consider all areas designated as occupied critical habitat here to meet the landscape specific PCE 1 and one or more of the seasonally specific PCEs (2-5). See our responses to comments 9 and 13. Each of the seasonally specific PCEs represents a unique seasonal habitat important for Gunnison sage-grouse survival and reproduction. Therefore, few areas would contain all seasonally specific PCEs. For instance, alternative, mesic habitats (PCE 5) may contain little to none of the sagebrush component generally required for the breeding, summer-fall, and winter habitats (PCEs 2-4).

(31) Comment: Several commenters asserted that a specific county (i.e., Dolores, Hinsdale, Ouray, or Saguache Counties in Colorado, or San Juan County in Utah) should be excluded from critical habitat designation.

Our Response: See our responses to comments 27 and 28. The five smaller populations included in this final designation outside of Gunnison Basin provide redundancy in the event of perturbations such as an outbreak of West Nile virus or the occurrence of drought, either of which could result in severe impacts to the Gunnison sage-grouse. The loss of one or more of the populations outside of Gunnison Basin could reduce the geographical distribution and total range of the Gunnison sage-grouse and increase the species' vulnerability to stochastic events and natural catastrophes, although the Poncha Pass population less so because it provides no unique genetic characteristics (since it is composed entirely of Gunnison Basin birds). These topics are discussed in detail in our final rule to list Gunnison sage-grouse as threatened, published elsewhere in today's Federal Register. The specific counties mentioned include portions of critical habitat designated for the Monticello-Dove Creek, San Miguel Basin, Cerro Summit-Cimarron-Sims Mesa, and Gunnison Basin populations and are essential for conservation of the species.

(32) Comment: Several commenters recommended that lands with an existing conservation plan, CEs, Certificates of Inclusion (CIs), or other protections for Gunnison sage-grouse either should or should not be excluded from critical habitat designation.

Our Response: Multiple partners including private citizens, nongovernmental organizations, a Tribe, and Tribal, State, and Federal agencies are engaged in conservation efforts across the range of Gunnison sage-grouse. Numerous conservation actions have been implemented for Gunnison sage-grouse, and these efforts have provided and will continue to provide conservation benefit to the species. In this final rule, as provided by section 4(b)(2) of the Act, we evaluate the benefits of including versus excluding lands covered under an existing conservation plan. Based on that evaluation, lands covered under the CCAA or CEs have been excluded from this final critical habitat designation. That evaluation also supported our decision to exclude the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe's Pinecrest Ranch in the Gunnison Basin area from the critical habitat designation, based on the Tribe's conservation plan for the ranch (see Exclusions). We are excluding 191,460 ac (77,481 ha) of proposed critical habitat on these conserved areas from the final designation.

(33) Comment: Several commenters presented differing opinions on whether or not energy and mineral exploration and production should be prohibited on critical habitat.