02-30890. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for Deinandra conjugens

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 76030

AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

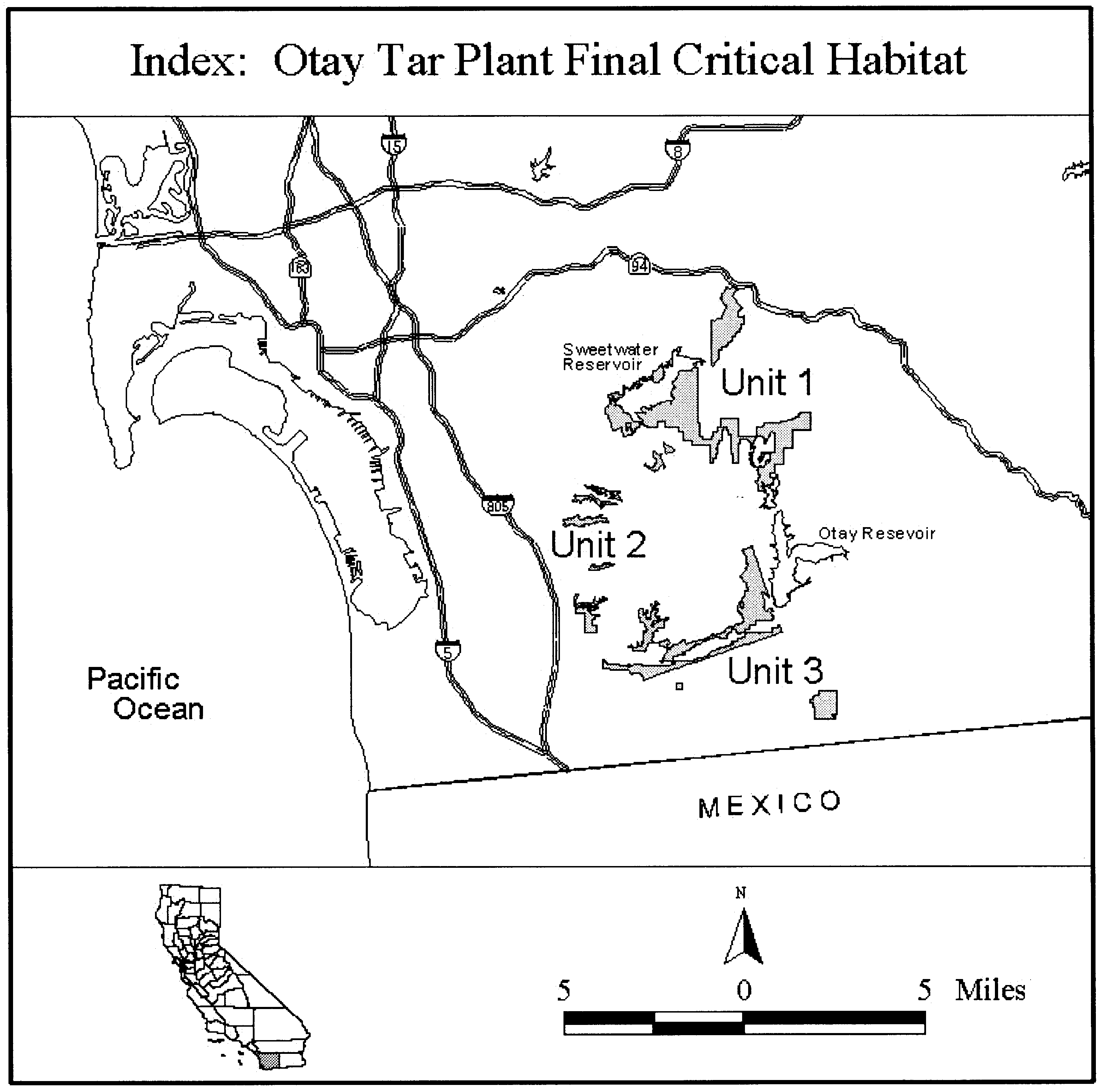

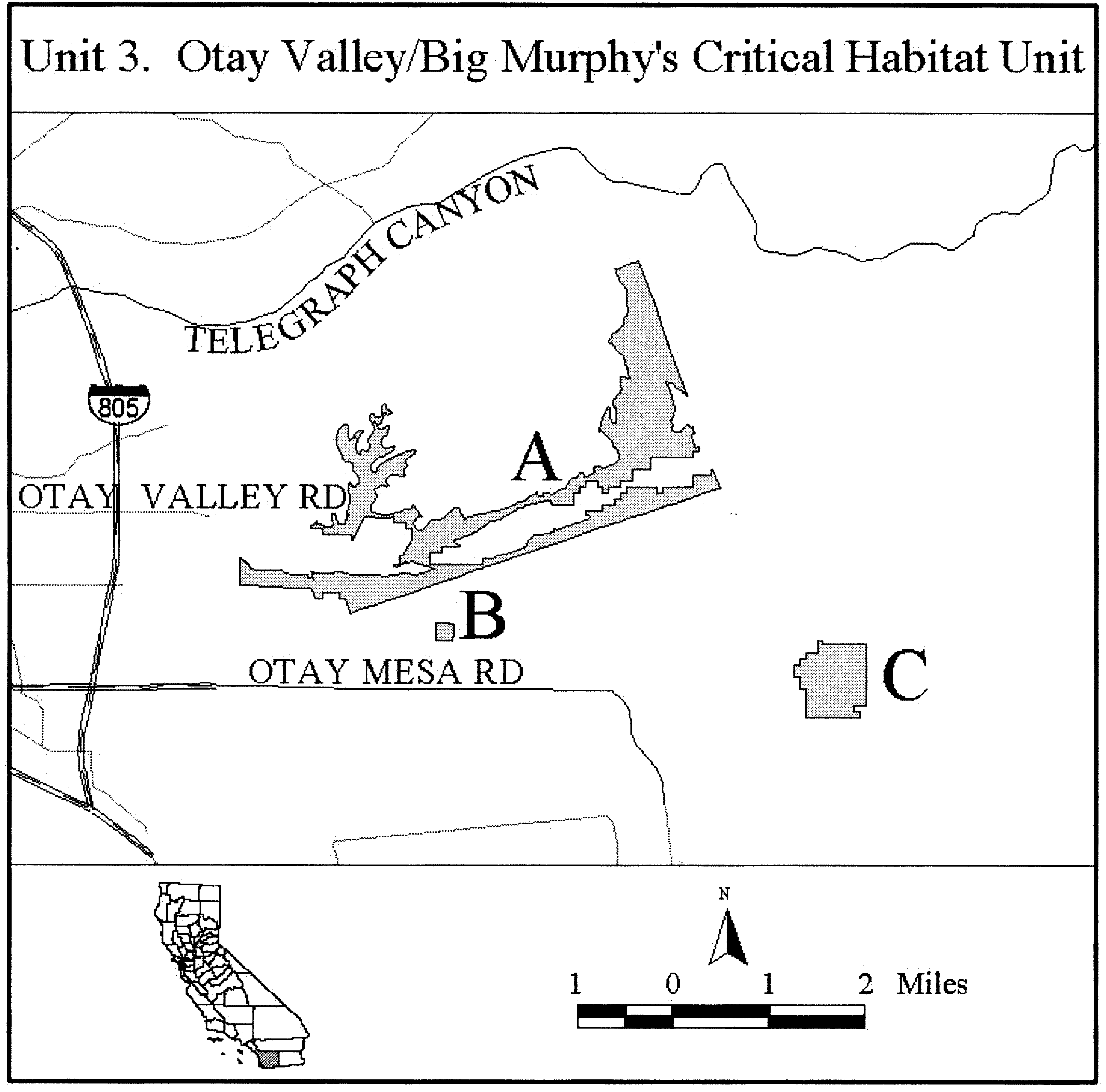

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), designate critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens [= Hemizonia conjugens] (Otay tarplant) pursuant to the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). Deinandra conjugens was federally listed as threatened (under the name Hemizonia conjugens) throughout its range in southwestern California and northwestern Estado de Baja California, Mexico in 1998. The designation includes approximately 2,560 hectares (ha) (6,330 acres (ac)) in San Diego County, California, as critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens.

DATES:

The effective date of this rule is January 9, 2003.

ADDRESSES:

You may inspect the supporting record for this rule at the Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 6010 Hidden Valley Road, Carlsbad, CA 92009, by appointment during normal business hours.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Jim Bartel, Field Supervisor, Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office, at the above address; telephone 760/431-9440, facsimile 760/431-5902. Information regarding this designation is available in alternate formats upon request.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Background

Deinandra conjugens (Otay tarplant) was known as Hemizonia conjugens when it was listed on October 13, 1998 (63 FR 54938). Since then, studies analyzing plant and floral morphology and genetic information prompted Baldwin (1999) to revise the Madiinae (tarplants), a tribe in the Asteraceae (sunflower family), and reclassify several taxa into new or different genera. As a result, Deinandra conjugens is now the accepted scientific name for Hemizonia conjugens. This taxonomic change does not alter the limits or definition of Deinandra conjugens. Because this taxonomic change was published and is generally accepted by the scientific community, we are changing the name of Hemizonia conjugens to Deinandra conjugens in 50 CFR 17.12 (h), and will use Deinandra conjugens in this final rule.

Deinandra conjugens was first described by David D. Keck (1958) as Hemizonia conjugens based on a specimen collected by L.R. Abrams in 1903 from river bottom land in the Otay Valley area of San Diego County, California. Deinandra conjugens is a glandular, aromatic annual plant in the Asteraceae. It has a branching stem that generally ranges from 5 to 25 centimeters (2 to 10 inches) in height with deep green or gray-green leaves covered with soft, shaggy hairs. The yellow flower heads are composed of 8 to 10 ray flowers and 13 to 21 disk flowers with hairless or sparingly downy corollas (fused petals). The phyllaries (small bracts associated with the flower heads) are ridged and have short-stalked glands and large, stalkless, flat glands near the margins. Deinandra conjugens occurs within the range of Deinandra fasciculata [=H. fasciculata] (fasciculated tarplant) and Deinandra paniculata [=H. paniculata] (San Diego tarplant). Deinandra conjugens can be distinguished from other members of the genus by its ridged phyllaries, black anthers (part of flower that produces pollen), and by the number of disk and ray flowers. The disk and ray flowers each produce different types of seeds (heterocarpy), which has been correlated to differential germination responses (Tanowitz et al. 1987).

Most known Deinandra conjugens occurrences are closely associated with particular soils, vegetation types, and elevation range. The majority of Deinandra conjugens occurrences are associated with clay soils and with grasslands, coastal sage scrub, or maritime succulent scrub. Information from herbarium records at the San Diego Natural History Museum (SDNHM) and data from the California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB 2002) records indicates that Deinandra conjugens has a narrow geographic and elevation range.

The distribution of Deinandra conjugens is strongly correlated with clayey soils, subsoils, or lenses (isolated area of clay soil) (Bauder et al. 2002). Such soils typically support grasslands, but may support some woody vegetation. Much of the area with clay soils and subsoils within the historical range of Deinandra conjugens likely was once vegetated with native grassland, open coastal sage scrub and maritime succulent scrub, which provided suitable habitat for Deinandra conjugens. Based on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis, most current and historical Deinandra conjugens occurrences are found on clay soils or lenses in one of the following soil series: Diablo; Olivenhain; Linne; Salinas; Huerhuero; Auld; Bosanko; Friant; and San Miguel-Exchequer rocky silt loams (Bauder et al. 2002).

The occurrence of Deinandra conjugens is also strongly associated with particular vegetation types. The species is found in vegetation communities classified as, but not limited to, grasslands, open coastal sage scrub, maritime succulent scrub, and the margins of some disturbed sites and cultivated fields (CNDDB 2002; Keck 1959; Keil 1993; CNPS 2001; David Hogan, San Diego Biodiversity Project, in litt. 1990; Bruce Baldwin, Jepson Herbarium, pers. comm., 2001; Mark Dodero, RECON, pers. comm., 2001; Scott McMillan, McMillan Biological Consulting, pers. comm., 2001). Plant species common to these vegetation communities include Nassella spp. (needlegrass), Bloomeria crocea (common goldenstar), Dichelostemma pulchella (blue dicks), Chlorogalum spp. (soap plant), Bromus spp. (brome grass), Avena spp. (oats), Deinandra fasciculata (fasciculated tarweed), Lasthenia californica (common goldfields), Artemisia californica (California sagebrush), Eriogonum fasciculatum (flat-top buckwheat), Lotus scoparius (deer weed), Salvia spp. (sage), Mimulus aurantiacus (bush monkeyflower), Malacothamnus fasciculatum (bushmallow), Malosma laurina (laurel sumac), Rhus ovata (sugar bush), R. integrifolia (lemonade berry), Lycium spp. (boxthorn), Euphorbia misera (cliff spurge), Simmondsia chinensis (jojoba), Opuntia spp. (prickly pear and cholla cactuses), Ferocactus viridescens (coastal barrel cactus), Ambrosia chenopodiifolia (San Diego bur sage), and Dudleya spp. (live-forevers).

Information acquired since the listing indicates that the historical range for Deinandra conjugens in San Diego County, California, is extended from the Mexican border north to Spring Valley and Paradise Valley, a distance of about 24 kilometers (km) (15 miles (mi)), and from Interstate 805 east to Otay Lakes Reservoir, a distance of about 13 km (8 mi) (herbarium records at the SDNHM and CNDDB 2002). Further, based on museum specimens and database records, the elevational range for Deinandra conjugens appears to be between 25 and 300 meters (m) (80 and 1,000 feet (ft)).

Typically, Deinandra conjugens and other tarplants cannot produce viable seeds without cross pollinating with Start Printed Page 76031other individuals (i.e., are essentially self-incompatible) (Keck 1959; Tanowitz 1982; B. Baldwin, in litt. 2001). Gene flow among plant populations through pollination is important for the long-term survival of self-incompatible species (Ellstrand 1992). Gene flow in Deinandra conjugens is essentially achieved through pollen movement among occurrences. Because small occurrences of Deinandra conjugens may facilitate greater gene flow, conservation of these may be critical to maintaining genetic diversity in Deinandra conjugens. Likely pollinators of Deinandra conjugens include, but are not limited to, bee flies (Bombylliidae); hover flies (Syrphidae); digger bees (Apidae); carpenter and cuckoo bees (Anthophoridae); leaf mason and leaf cutting bees (Megachilidae); and metallic bees (Halictidae) (Krombein et al. 1979; Bauder et al. 2002; M. Dodero, pers. comm., 2001). The following bee species have been documented visiting Deinandra species: Nomia melanderi; Colletes angelicus; Nomadopsis helianthi; Ventralis claypolei ausralior; Anthidiellum notatum robertsoni; Heriades occidentalis; Anthocopa hemizoniae; Ashmeadiella californica californica; Svastra sabinensis nubila; Melissodes tessellata; M. moorei; M. personatella; M. robustior; M. semilupina; M. lupina; M. stearnsi; Anthophora urbana urbana; and A. curta curta (Krombein et al. 1979).

Deinandra conjugens fruits are each one-seeded and are likely to be dispersed by small to large-sized mammals and birds based on the sticky nature of the remaining flower parts that are attached to the fruits and the discontinuous distribution of other tarplants (B. Baldwin, in litt. 2001; M. Dodero, pers. comm., 2001; Elizabeth Friar, Claremont Graduate University, pers. comm., 2001; Gjon Hazard, (Service), pers. comm., 2001). Potential seed/fruit dispersal organisms known to occur in the region include, but are not limited to, mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), coyote (Canis latrans), black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus bennettii), bobcat (Felis rufus), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), opossum (Didelphis virginiana), racoon (Procyon lotor), and various small land birds.

A seed bank (a reserve of dormant seeds, generally found in the soil) is important for year-to-year and long-term survival (Given 1994, Rice 1989). A seed bank includes all of the seeds in a population and generally covers a larger area than the extent of observable plants seen in a given year. The number and location of standing plants in a population varies annually due to a number of factors, including the amount and timing of rainfall, temperature, soil conditions, and the extent and nature of the seed bank. Large annual fluctuations in the number of standing plants in a given population have been documented. Population size has ranged from 1 to over 5,400 standing plants at a site on northwest Otay Mesa (CNDDB 2002; City of San Diego, in litt. 1999), from approximately 100 to 50,000 at a site in Rice Canyon (CNDDB 2002), and from approximately 280,000 to 1.9 million at San Miguel Ranch South (CNDDB 2002; Merkel & Associates, in litt. 1999). In any given year, the observable plants in a population are only the portion of the individuals from the seed bank that germinated that year. These annual fluctuations make it look as though a population of annual plants “moves” from year to year, when in actuality, a different portion of a population germinates and flowers each year. The spatial distribution of a standing population of annual plants is generally the result of the spatial distribution of the micro-environmental conditions conducive to seed germination and growth of the plants.

Determining the size or magnitude of a given Deinandra conjugens population is difficult due to the major fluctuations that have been documented in known populations (CNDDB 2002; Merkel & Associates, in litt. 1999). Conditions during some years are better for growth and reproduction of Deinandra conjugens in some populations (and even some portions of a population) than during other years. Because the number of standing plants in a given population can vary by orders of magnitude from one year to the next, the number of standing plants observed in a population in any one year does not necessarily indicate the potential magnitude of that population.

Deinandra conjugens has a limited distribution consisting of at least 25 historical populations near Otay Mesa in southern San Diego County and one population in Estado de Baja California, Mexico, near the United States border (CDFG 1994; Roberts 1997; CNDDB 2002; Reiser 1996; herbarium records at the SDNHM; S. Morey, in litt. 1994). Three of the 25 historic populations of Deinandra conjugens in the United States are considered to be extirpated (CNDDB 2002; D. Hogan, in litt. 1990; S. Morey, in litt. 1994).

The largest number of Deinandra conjugens plants were recorded in 1998 when it was estimated that there were over 2 million individuals for the species as a whole (CNDDB 2002; Merkel & Associates, in litt. 1999). However, the number of standing plants from year to year can be highly variable. As testament to this variability, the species was thought to be extinct within its range until its rediscovery in Estado de Baja California, Mexico in 1977 (Tanowitz 1978). Conversely, the largest population (Rancho San Miguel) supported about 1.9 million plants during 1998 when southern California experienced El Nino weather conditions, which resulted in a particularly wet and prolonged growing season (Merkel & Associates, in litt. 1999).

By 1998, the five largest populations of Deinandra conjugens (Rancho San Miguel, Rice Canyon, Dennery Canyon, Poggi Canyon, and Proctor Valley) were known to support about 98 percent of all reported standing plants (CNDDB 2002; San Diego Gas and Electric 1995; Roberts 1997; Merkel & Associates, in litt. 1999; Morey, in litt. 1994; City of Chula Vista 1992; Brenda Stone, California Department of Transportation, in litt. 1994) with each reportedly containing more than 10,000 standing plants. In 2000, surveys for Deinandra conjugens conducted in Johnson Canyon (Helix Environmental Planning, Inc. 2001b) and Rolling Hills Ranch (Helix Environmental Planning, Inc. 2001a), identified new populations estimated to include approximately 480,000 and 28,000 standing plants, respectively. Of the remaining populations, 8 are reported to support from 1,000 to 8,000 plants each; 9 are reported to support fewer than 1,000 plants each; and 3 are considered to be extirpated (CNDDB 2002). All of the above referenced populations occur on Federal, local, and private lands (CNDDB 2002).

Some of the smaller populations of Deinandra conjugens are believed to be essential to the survival and conservation of the species because they are strategically located between larger populations and likely facilitate gene flow among them. Gene flow among populations has been demonstrated to reduce local and global extinctions in a number of species (Hanski 1998; Baldwin, in litt. 2001). Processes such as mutation, genetic migration, and random genetic drift are known to adversely affect small populations (Barrett and Kohn 1991). Adverse effects from these processes on Deinandra conjugens would likely be magnified by its self-incompatibility (Keck 1959; Tanowitz 1982; Baldwin, in litt. 2001). Maintaining gene flow among occurrences and between populations is essential to counter the adverse effects from the processes mentioned above, Start Printed Page 76032and to ensure the long-term survival and conservation of this species.

At the time the species was listed in 1998, we estimated that 70 percent of the suitable habitat for this species within its known range had been lost to development or agriculture (63 FR 54938). Since the listing, additional habitat has been lost to development (e.g., urban, commercial, industrial, residential) and agriculture (e.g., grazing, farming).

Deinandra conjugens appears to tolerate mild levels of disturbance such as light grazing (Hogan, in litt. 1990; Tanowitz, in litt. 1977). Such mild disturbances may result in habitat conducive to germination (Tanowitz, in litt. 1977). However, the species is otherwise threatened by urbanization and related activities, intensive agriculture, and the invasion of non-native species, which may result in significant disturbance to populations (63 FR 54938). Because of these threats, we anticipate that intensive long-term monitoring and management may be needed to protect and conserve this species.

At the time the species was listed in 1998, we estimated that about 11,930 ha (30,310 ac) of land with clay soils or clay subsoils were within the general range of Deinandra conjugens in San Diego County, California (63 FR 54938). Also at that time, about 4,200 ha (10,600 ac) (about 37 percent) of this area had been urbanized and about 4,155 ha (10,555 ac) (about 37 percent) had been heavily cultivated and grazed (63 FR 54938). Additional areas have been lost to urbanization since this time. New information from herbarium records at the SDNHM indicates that the historical range of Deinandra conjugens extended further to the north and northwest. Most of the habitat in this additional area has already been lost to development. Much of the cultivated and grazed lands in this range could be restored to support Deinandra conjugens, which can grow in the margins of cultivated fields (S. McMillan, pers. comm., 2001; M. Dodero, pers. comm., 2001). However, most of these lands will likely be unavailable for the species because of proposed urban and agricultural land use (Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office GIS database 2002 which includes coverages from San Diego Association of Governments).

Previous Federal Action

On December 15, 1980, we published a Notice of Review (NOR) of plants which included Deinandra conjugens as a category 1 candidate taxon (45 FR 82480). Category 1 taxa were those taxa for which substantial information on biological vulnerability and threats are available to support preparation of listing proposals. On November 28, 1983, we published a supplement to the 1980 NOR that treated Deinandra conjugens as category 2 candidate taxa (48 FR 53640). Category 2 candidates were taxa for which data in our possession indicated listing was “possibly appropriate but for which substantial information on biological vulnerability and threats were not known or on file to support preparation of proposed rules” (48 FR 53640).

On December 14, 1990, we received a petition dated December 5, 1990, from Mr. David Hogan of the San Diego Biodiversity Project, to list Deinandra conjugens as endangered. The petition also requested designation of critical habitat. Because Deinandra conjugens was included in the Smithsonian Institution's Report of 1975, designated as House Document No. 94-51, that had been accepted as a petition, we regarded Mr. Hogan's petition to list this taxon as a second petition. We responded to the petition by publishing a proposed rule to list Deinandra conjugens as endangered on August 9, 1995 (60 FR 40549). On October 13, 1998, we published a final rule listing Deinandra conjugens as threatened (63 FR 54938). At that time, we indicated that designation of critical habitat was not prudent.

On July 15, 1999, the California Native Plant Society (CNPS) and Southwest Center for Biological Diversity (SWCBD) filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California, in part, challenging our decision not to designate critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens (California Native Plant Society; et al. v. Babbitt, et al., 99CV1454 L (S.D.Cal.). On December 21, 2000, we entered into a stipulated settlement agreement with the plaintiffs under which we agreed to reevaluate the prudency determination for Deinandra conjugens by May 30, 2001. If we determined that critical habitat was prudent, we were to publish a proposed rule to designate critical habitat by June 5, 2000, with a final determination to be completed by May 30, 2002. On June 1, 2001, we determined that designation of critical habitat was prudent, and on June 13, 2001, we published in the Federal Register a proposed rule to designate approximately 2,685 ha (6,630 ac) of land as critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens (66 FR 32052). We requested a 6-month extension (until November 30, 2002) to complete the final designation to allow us adequate time to complete an economic analysis, obtain public comment on the economic analysis, and complete the final designation. This extension was agreed to by the plaintiffs and approved by the court on June 2, 2002. On July 10, 2002, we published a notice reopening the public comment period on the proposed rule for an additional 30 days and announcing the availability of the draft economic analysis (67 FR 45696). This final critical habitat designation is consistent with the settlement agreement.

Summary of Comments and Recommendations

In the June 13, 2001, proposed critical habitat designation (66 FR 32052), we requested all interested parties to submit comments on the specifics of the proposal including information related to biological justification, policy, economics, and proposed critical habitat boundaries. The initial 60-day comment period closed on August 13, 2001. The comment period was reopened from July 10, 2002, to August 9, 2002 (67 FR 45969), to allow for additional comments on the proposed designation, and comments on the draft economic analysis of the proposed critical habitat.

We contacted all appropriate State and Federal agencies, county governments, elected officials, and other interested parties and invited them to comment. In addition, on June 13, 2001, we invited public comment through the publication of a legal notice in the San Diego Union-Tribune newspaper in southern California. We provided notification of the draft economic analysis to all interested parties. This was accomplished through telephone calls, letters, and news releases faxed and/or mailed to affected elected officials, media outlets, local jurisdictions, and interest groups. We also posted the proposed rule and draft economic analysis and associated material on our Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office internet site following their release on June 13, 2001, and July 10, 2002, respectively.

We received a total of 11 comment letters, from 8 separate parties during the two public comment periods. Comments were received from Federal and local agencies, and private organizations and individuals. No response was received from State agencies. Of these 11 comment letters, 4 were in favor of the designation, and 7 against it. We reviewed all comments received for substantive issues and comments, and new information regarding Deinandra conjugens. Similar comments were grouped into three general issues relating specifically to the proposed critical habitat determination Start Printed Page 76033and draft economic analysis on the proposed determination.

Peer Review

We requested four biologists, who have knowledge of Deinandra conjugens, to provide peer review of the proposed designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens. Two of the four peer reviewers submitted comments on the proposed designation. Both reviewers strongly endorsed the proposal, citing the importance of genetic diversity to the survival of Deinandra conjugens. One reviewer supported our inclusion of living seed banks, in areas where plants are not evident every year, and concurred that we fully considered in the proposal the importance of genetic diversity found in major and minor populations.

Comments were either incorporated directly into the final rule or final addendum to the economic analysis or addressed in the following summary.

Issue 1: Biological Justification and Methodology

Comment 1: One commenter expressed concern over eliminating areas with negative survey results from analysis where there may be primary constituent elements and thereby eliminating them from potential inclusion in critical habitat.

Our Response: The definition of critical habitat in section 3(5)(A) of the Act includes “(i) specific areas within the geographic area occupied by a species, at the time it is listed in accordance with the Act, on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protection; and (ii) specific areas outside the geographic area occupied by a species at the time it is listed, upon a determination that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species.” The term “conservation,” as defined in section 3(3) of the Act, means “to use and the use of all methods and procedures which are necessary to bring any endangered species or threatened species to the point at which the measures provided pursuant to the Act are no longer necessary” (i.e., the species is recovered and removed from the List of Endangered and Threatened Species).

As we discussed in our proposed critical habitat for the Deinandra conjugens, we identified those areas that currently contain populations or provide habitat components essential to the conservation of Deinandra conjugens. We excluded some areas where Deinandra conjugens has not been observed historically or recently because we cannot document that these areas are essential for the conservation of the species. However, we proposed for designation those areas that we believe to be essential, that possess core populations, and have unique ecological characteristics.

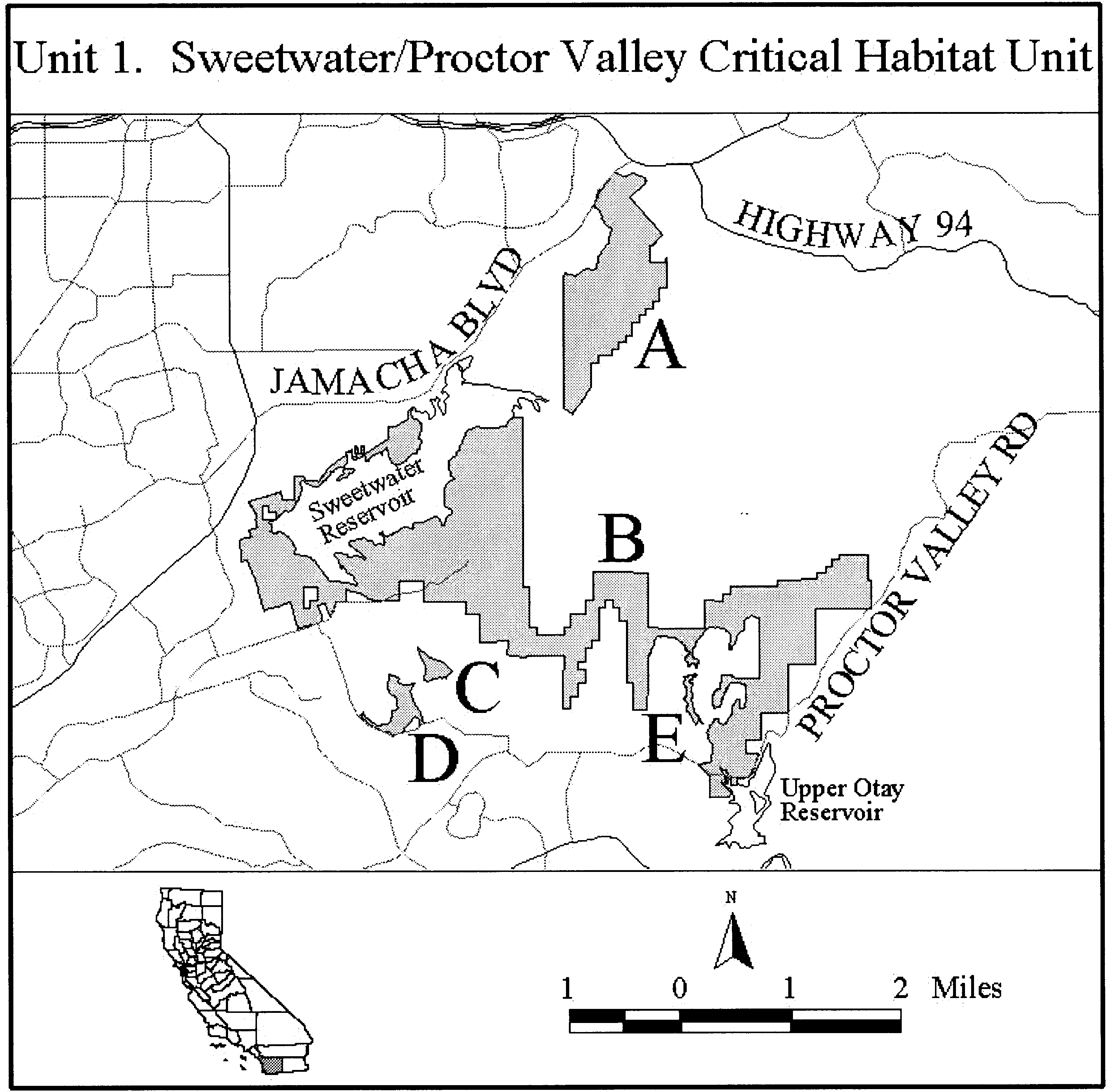

Comment 2: One commenter expressed concern that the most current and therefore, the best scientific data available for the Rolling Hills Ranch project was not used. The commenter further suggests that the proposed rule underestimates the number of Deinandra conjugens individuals located on Rolling Hills Ranch, specifically, that 2000 survey data submitted to the Service in April and July of 2001 should be used to redefine the critical habitat boundaries at Rolling Hills Ranch.

Our Response: As discussed in the proposed rule, we did rely on the most recent data from the 2000 survey season at Rolling Hills Ranch to develop the Unit 1 boundaries of proposed critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens. The subject 2000 survey data was provided to the Service in April 2001, prior to the proposal. This data for the most part, corroborated decisions made during the development of the proposed critical habitat rule, and identified new areas of occupancy at Rolling Hills Ranch. Some of these areas within the proposed critical habitat, in which Deinandra conjugens was documented for the first time in 2000, have not been included in the final designation for reasons discussed in this rulemaking. The occurrence data and supporting documentation used in the rulemaking are available for inspection at the Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office by appointment (please see ADDRESSES section of this rule).

Comment 3: One commenter questioned the biological justification for proposing critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens using a landscape-scale approach when they believed that more precise information is available for use by the Service.

Our Response: We recognize that not every parcel of land within the external boundaries of the critical habitat designation will contain the habitat components essential to the conservation of Deinandra conjugens. In the absence of more detailed map information during the preparation of the proposed and final designations, we used a 100-m UTM grid and hardline reserve boundaries to delineate critical habitat.

In developing the proposed rule and this final designation, we made an effort to minimize the inclusion of areas that do not contain the primary constituent elements for Deinandra conjugens. However, due to our mapping scale, some areas not essential to the conservation of Deinandra conjugens are included within the boundaries of proposed and final critical habitat. These areas, such as existing housing developments, roads, or other developed lands do not provide habitat for Deinandra conjugens. Because they do not contain one or more of the primary constituent elements for the species, Federal actions limited to those areas will not trigger a section 7 consultation of the Act, unless they affect the species or primary constituent elements in adjacent critical habitat.

Comment 4: One commenter expressed concern that the proposed critical habitat does not encompass all areas needed to provide for genetic exchange between occurrences of Deinandra conjugens. For instance, Map Units 2 and 3 result in genetically isolated areas of critical habitat; pollinators and seed dispersers would not be capable of maintaining genetic exchange among these and other critical habitat areas. Also, Unit 2F, 2G, and 2H, and Unit 3A should be one interconnected unit; there is no scientific justification for segregating these areas into separate polygons.

Our Response: In developing the proposed critical habitat, we evaluated those areas essential to the conservation of Deinandra conjugens and that are covered by a legally operative Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP). Those areas believed to be biologically essential, but already covered by a legally operative HCP, were excluded from this designation pursuant to section 4(b)(2) of the Act. Consequently, those areas within the subject critical habitat units containing essential Deinandra conjugens habitat within the San Diego County Subarea Plan of the San Diego County Multiple Species Conservation Plan (MSCP) are excluded. These exclusions create the appearance of habitat gaps that could limit genetic exchange. Though some of these gap areas do not contain primary constituent elements, most gap areas include lands conserved under existing HCPs. After evaluating the relative locations of populations, and evaluating their genetic exchange potential, we only designated areas determined to be essential that require special management. Because areas conserved in reserves under existing HCPs receive special management pursuant to those plans, they were not included in proposed or final critical habitat. Start Printed Page 76034

Issue 2: Policy and Regulations

Comment 5: One commenter suggested that designating critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens on San Miguel Ranch project lands that will become part of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge (SDNWR) is not adequate to provide the necessary and appropriate levels of assurance to San Miguel Ranch. The commenter explained that San Miguel Ranch, as a third party beneficiary to the MSCP Implementing Agreement, is covered by an existing legally operative HCP that addresses Deinandra conjugens. Finally, the commenter suggests that, due to the conservation protections and management measures assured for Deinandra conjugens through the SDNWR Annexation Agreement, the benefits of excluding San Miguel Ranch outweigh the benefits of including of San Miguel Ranch in the designation.

Our Response: Pursuant to section 4(b)(2) of the Act, we may exclude any area from designated critical habitat if we believe that the benefits of excluding such lands outweigh the benefits of including those lands in critical habitat, providing that the exclusion would not result in the extinction of the species. We have generally excluded from critical habitat areas within legally operative HCPs that “cover” the subject species by protecting, and providing management for, the essential habitat of the species within the plan area. We have used the provisions of section 4(b)(2) of the Act for the exclusion of lands covered by approved HCPs, because we believe that the benefits of excluding them outweigh the benefits of including them.

Prior to annexation by the City of Chula Vista, the San Miguel Ranch project was covered under the County of San Diego's approved and legally operative Subarea HCP. In 2000, that portion of the County of San Diego's incidental take permit that covers San Miguel Ranch was transferred to the City of Chula Vista. Under the County of San Diego Subarea Plan Implementing Agreement, the County and third party beneficiaries, as that term is defined in the Implementing Agreement, are assured that if the critical habitat is designated, they will not be required to provide additional mitigation beyond that imposed on their project in accordance with the Subarea Plan without their consent. Those assurances continue to extend to San Miguel Ranch, to the extent it maintains third party beneficiary status, with the transfer of that portion of the County of San Diego's incidental take permit that covers San Miguel Ranch to the City of Chula Vista in year 2000. The assurance is not affected or diminished by the designation.

Under the Annexation Agreement, Trimark (the project proponent) has limited rights to encroach on certain SDNWR lands and the right to request an encroachment easement on other SDNWR lands. If the Service approves such encroachment, Trimark is required to provide mitigation as described in the Annexation Agreement. The inclusion of SDNWR lands in critical habitat does not conflict with the Annexation Agreement or interfere with any assurances provided to the San Miguel Ranch project under the transferred County permit. While San Miguel Ranch is covered by a legally operative HCP, those lands identified for transfer to the SDNWR under the Annexation Agreement will become federal lands conserved and managed by the Service in accordance with Annexation Agreement and the laws and regulations governing the National Wildlife Refuge System. Therefore the considerations underlying out exclusion of lands within approved HCPs under 4(b)(2) of the Act do not apply here. The Service has not completed a Comprehensive Management Plan and Step-down Refuge Management Plan that adequately addresses management and monitoring of Deinandra conjugens. Thus the refuge lands, which we have determined are essential for the conservation of Deinandra conjugens, continue to require special management and thus meet the definition of critical habitat under section 3(5)(A) of the Act. Finally, because the SDNWR lands are federal lands, Section 7, which is the primary regulatory benefit of designating lands as critical habitat, will apply to activities carried out on the lands. We are not aware of any facts that indicate that the benefits of excluding the SDNWR lands from critical habitat under section 4(b)(2) of the Act would outweigh the benefits of including them as critical habitat.

Comment 6: Several commenters suggested that the final critical habitat boundary should be consistent with boundaries of the reserves being established under the Chula Vista Subarea Plan of the San Diego County MSCP (e.g., Rolling Hills Ranch and Bella Lago).

Our Response: As previously discussed in this rulemaking, we proposed to designate as critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens those lands believed to be essential to the conservation of the species. During the development of the proposal, we took into consideration the most current and best commercial and scientific data available. This information included the conservation management and protections afforded Deinandra conjugens under the San Diego County MSCP and the Chula Vista Subarea Plan currently being developed. The boundaries of our proposed critical habitat designation in some areas matched those of the proposed reserve for the Chula Vista Subarea Plan, because in our analysis of the subarea plan, we concluded that these boundaries incorporated areas essential to the conservation of Deinandra conjugens. For reasons discussed in the Critical Habitat section of this rulemaking, we reevaluated and ultimately modified the critical habitat boundaries at Rolling Hills Ranch and Bella Lago. The modifications reflect the results of additional analysis of Deinandra conjugens habitat within the projects' boundaries and discussions regarding conservation of essential habitat with the project proponents and the outcome of a Section 7 conference opinions on Bella Lago and Rolling Hills Ranch. The reserve boundaries for the Chula Vista subarea plan currently out for review, including Bella Lago and Rolling Hills Ranch, are consistent with this final rule.

Comment 7: One commenter requested that we conduct the analysis necessary to conclude that the City of Chula Vista's proposed MSCP Subarea Plan should be excluded from the critical habitat designation pursuant to section 4(b)(2) of the Act. The commenter asserts that we should withdraw and revise the proposed critical habitat designation to include an analysis and finding that the benefits of excluding the City's plan outweigh the benefits of inclusion.

Our Response: Section 4(b)(2) of the Act allows us to exclude from critical habitat designation areas where the benefits of exclusion outweigh the benefits of designation, provided the exclusion will not result in the extinction of the species. We believe that in most instances the benefits of excluding legally operative HCPs from critical habitat designations will outweigh the benefits of including them. Deinandra conjugens is a covered species in the proposed Chula Vista Subarea Plan; however, the Subarea Plan is not yet approved or legally operative. The plan has been released to the public for review and may be revised as a result of comments received by the public. The Service has not conducted a review of the plan under section 7 or section 10 of the Act to determine whether it meets the criteria for issuance of an incidental take permit. Nor has the Service completed Start Printed Page 76035its review of the plan under NEPA. Exclusion of the plan area under section 4(b)(2) of the Act based on a proposed plan that may change and that has not been approved by the Service would be inappropriate.

We anticipate that the Chula Vista Subarea Plan and other future HCPs in the range of Deinandra conjugens will include it as a covered species and provide for its long-term conservation. If the Chula Vista Subarea Plan or other HC056that address Deinandra conjugens as a covered species are ultimately approved and legally operative, we may reassess the critical habitat boundaries in light of the approved HCP.

Comment 8: One commenter expressed concern that we did not sufficiently support our decision to reverse our determination that designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens is not “prudent.” Finally, the commenter requests that we withdraw and reconsider our determination that designation of critical habitat is now prudent.

Our Response: In our final rule listing Deinandra (= Hemizonia) conjugens as threatened under the Act (63 FR 549384), we found that designation of critical habitat was not prudent because it occurs primarily on private lands with little or no Federal involvement. As we discuss in the Previous Federal Action section of this final rule, we were challenged on our original “not prudent” finding. On December 21, 2000, we agreed to a stipulated settlement that required us to publish a proposal to withdraw the existing “not prudent” critical habitat determination and make a new prudency determination. In the Prudency Determination section of the proposed rule, we detailed our reasoning for determining that critical habitat is, in fact, prudent for Deinandra conjugens. In general, we concluded that there may be some additional benefits to designating critical habitat, including instances where section 7 consultation would be triggered only if critical habitat is designated, educational or informational benefits to designating critical habitat, and significant occurrences of Deinandra conjugens that have come under Federal lands jurisdiction since the time of listing. The publication of our June 13, 2001, proposal and this final rule are in compliance with that determination and the stipulated settlement agreement and subsequent court orders.

Comment 9: One commenter suggested that lands covered by the MSCP (or other HCPs) do not provide adequate protection for long-term conservation of Deinandra conjugens; as such, the small disjunct critical habitat areas as currently proposed are inadequate to support the long-term survival of Deinandra conjugens.

Our Response: Deinaindra conjugens is a covered species under the City and County of San Diego subarea plans of the MSCP. As discussed later in this rule, Section 10(a)(1)(B) of the Act authorizes the Service to issue to non-Federal entities a permit for the take of endangered and threatened animal species incidental to otherwise lawful activities. An incidental take permit must be supported by an HCP that identifies conservation measures that minimize and mitigate the impacts of take of covered animal species to the maximum extent practicable and that we believe necessary to reduce project-related effects to the extent that they do not appreciably reduce the likelihood of the survival and recovery of the species in the wild. Where an HCP includes sufficient conservation measures to preclude jeopardy for listed plant species, we will also include such species on the incidental take permit in recognition of those conservation benefits even though take of listed plant species is not prohibited under Section 9 of the Act.

In the proposed rule we discussed at length the relative benefits of including or excluding from critical habitat lands covered by a legally operative HCP that includes Deinandra conjugens as a covered species (see 66 FR 32060-61). In particular we noted that the benefits of including HCP lands in critical habitat are normally small to non-existent because approved HCPs are already designed to ensure the long-term survival of covered species. HCPs typically protect essential habitat in reserves that are managed to protect, restore, and enhance their value as habitat for the species. Moreover, before approving an HCP or issuing an incidental take permit, we complete a section 7 of the Act consultation on the proposed permit and must conclude that the permit will not result in jeopardy to any covered species in the plan area.

The reserves established under the approved MSCP subarea plans include essential populations of Deinandra. Those areas we are designating as critical habitat include essential habitat for Deinandra conjugens within HCPs that are currently under development, but have not yet been approved, and other essential habitat outside of approved HCPs. The critical habitat designation provides connectivity among Deinandra conjugens populations protected within reserves established under approved subarea plans.

Comment 10: One commenter concluded that all lands containing the species' primary constituent elements are essential to the conservation of the species.

Our Response: By definition (see sections 3(5)(A) and 3(5)(C) of the Act), essential critical habitat generally describes a subset of the area potentially containing primary constituent elements for a species. As discussed in the methods section of the proposed and this final rule, to determine areas essential for the conservation of Deinandra conjugens, we used the best scientific and commercial data available pertaining to known habitat requirements of the species. Areas designated as critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens are within the current known range of the species and contain one or more primary constituent elements essential for the conservation of the species. In our proposed and final designation of critical habitat, we selected essential habitat areas based on occurrence data, soils, vegetation, elevation, topography, and current land uses. During this analysis, it was determined that some areas containing one or more primary constituent elements did not represent suitable habitat or were otherwise not essential for the conservation of the species.

Issue 3: Economic Issues

Comment 11: One commenter expressed concern that the deferral of economic and other relevant impacts in preparing the proposed rule violates the requirements of the Act. The commenter acknowledges our position from previous critical habitat designations pursuant to the specific implementing regulations (50 CFR 424.19) that it is not required by law to conduct an economic analysis at the time critical habitat is initially proposed. The commenter asserts, however, that the implementing regulations contradict the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533(b)(2)) (i.e., section 4(b)(2) of the Act), whereas the statute calls for designation of critical habitat after taking into consideration economic impacts of specifying any particular area as critical habitat. The commenter suggests that we ignored economic effects and other related effects until after critical habitat boundaries are established. Conversely, the commenter asks how the proposed rule text can suggest that “the designation of critical habitat is not likely to result in a significant regulatory burden above that already in place due to the presence of listed species,” if an economic analysis has not yet been conducted. Start Printed Page 76036

Our Response: Pursuant to section 4(b)(2) of the Act, we designate critical habitat and make revisions thereto on the basis of the best available scientific data and after taking into consideration economic impacts and other relevant impacts associated with the designation. We published our proposed designation in the Federal Register on June 13, 2001 (66 FR 32052). At that time, our Division of Economics and their consultants, Industrial Economics, Inc., initiated the draft economic analysis. The draft economic analysis was made available for public comment and review beginning on July 10, 2002 (67 FR 45696). Following a 30-day public comment period on the proposal and draft economic analysis, a final addendum to the economic analysis was completed which takes into consideration public comments. Both the draft economic analysis and the addendum were used in the development of this final designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens. Please refer to the Economic Analysis section of this final rule for a more detailed discussion of these documents. Therefore, our designation of critical habitat does take into consideration economic and other impacts considered during the rulemaking process.

As stated earlier in this final rule, Federal agencies already consult with us on activities in areas currently occupied by Deinandra conjugens, or if the species may be affected by the action, to ensure that their actions do not jeopardize the continued existence of the species. Since Deinandra conjugens critical habitat is considered occupied by either standing plants or seed bank, and we already consult on other listed species, including the coastal California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica californica) and the Quino checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha quino), that have designated critical habitats that overlap with Deinandra conjugens, we do not anticipate a significant additional regulatory burden will result from the designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens. We made our anticipatory statement that the designation of critical habitat was not likely to result in a significantly higher regulatory burden based on the information available at the time. The economic analysis has demonstrated that our initial assumption was correct.

Comment 12: One commenter suggested that the Service failed to take into account the cumulative economic impacts of all the existing and proposed critical habitat designations. The commenter believes that the Act and relevant Federal cases (New Mexico Cattle Growers v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 248 F.3d 1277, 1281-1285) require this type of analysis and requests that the Service explain the factual and legal basis for its decision that other pending and final critical habitat designations can be considered separately.

Our Response: The commenter appears to be using the term “cumulative impacts” in the context of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which does not apply to this rulemaking. See the National Environmental Policy Act section of this rule. We are required to consider only the effect of the proposed government action, which in this case is the designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens. The appropriate baseline for use in this analysis is the regulatory environment without this regulation. While, consistent with New Mexico Cattlegrowers v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, we considered the costs and benefits of both the listing of Deinandra conjugens and the designation of critical habitat for this species in establishing an upward estimate of economic effects, and then attempted to identify and measure the additional costs and benefits associated with this designation of critical habitat, when critical habitat for other species has already been designated, it is properly considered part of the baseline for this analysis. Proposed and future critical habitat designations for other species in the area will be part of separate rulemakings, and consequently, their economic effects will be considered separately.

Comment 13: One commenter suggested that the critical habitat designation triggers “No Surprises” regulations due to Deinandra conjugens” coverage in the MSCP, and that we should pay all the costs associated with the designation.

Our Response: Permittees and third party beneficiaries, as the term is defined under various MSCP Subarea Plan Implementing Agreements, are assured that in the event critical habitat is designated for a covered species, such as Deinandra conjugens, within the boundaries of approved subarea plans, they will not be required to provide additional mitigation consisting of money, land or restrictions on land, beyond the level of mitigation imposed on their projects in accordance with the subarea plans without their consent. The designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens does not undermine, compromise or affect that assurance or trigger the No Surprises regulation.

Comment 14: One commenter expressed concern that the critical habitat methodology fails to meet the standards of the Act as held by the 10th Circuit Court [New Mexico Cattle Growers Ass'n v. U.S.F.W.S., 248 F.3rd 1277 (10th Cir. 2001)] in that the economic analysis cannot be separated from the action listing the species.

Our Response: In New Mexico Cattle Growers Ass'n v. U.S.F.W.S., 248 F.3d 1277 (10th Cir. 2001) the 10th Circuit recently held that the baseline approach to economic analysis of critical habitat designations that was used by the Service for the southwestern willow flycatcher designation was “not in accord with the language or intent of the ESA.” In particular, the court was concerned that the Service had failed to analyze any economic impact that would result from the designation, because it took the position in the economic analysis that there was no economic impact from critical habitat that was incremental to, rather than merely co-extensive with, the economic impact of listing the species. The Service had therefore assigned all of the possible impacts of designation to the listing of the species, without acknowledging any uncertainty in this conclusion or considering such potential impacts as transaction costs, reinitiations, or indirect costs. The court rejected the baseline approach incorporated in that designation, concluding that, by obviating the need to perform any analysis of economic impacts, such an approach rendered the economic analysis requirement meaningless.

In this analysis, the Service addresses the 10th Circuit's concern that we give meaning to the ESA's requirement of considering the economic impacts of designation by acknowledging the uncertainty of assigning certain post-designation economic impacts (particularly section 7 consultations) as having resulted from either the listing or the designation. We also understand that the public wants to know more about the kinds of costs consultations impose and frequently believe that designation could require additional project modifications.

Therefore, this analysis incorporates two baselines. One addresses the impacts of critical habitat designation that may be attributable co-extensively to the listing of the species. Because of the potential uncertainty about the benefits and economic costs resulting from critical habitat designations, we believe it is reasonable to estimate the upper bounds of the cost of project modifications based on the benefits and economic costs of project modifications that would be required due to consultation under the jeopardy Start Printed Page 76037standard. It is important to note that the inclusion of impacts attributable co-extensively to the listing does not convert the economic analysis into a tool to be considered in the context of a listing decision. As the court reaffirmed in the southwestern willow flycatcher decision, “the ESA clearly bars economic considerations from having a seat at the table when the listing determination is being made.”

The other baseline, the lower boundary baseline, will be a more traditional rulemaking baseline. It will attempt to provide the Service's best analysis of which of the effects of future consultations actually result from the regulatory action under review—i.e., the critical habitat designation. These costs will in most cases be the costs of additional consultations, reinitiated consultations, and additional project modifications that would not have been required under the jeopardy standard alone as well as costs resulting from uncertainty and perception impacts on markets. The final addendum to this analysis provides further information concerning the baseline and potential incremental effects of the designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens.

Comment 15: One commenter suggested that the economic analysis cannot rely on overlap between Federal laws and State and local regulations. The analysis of State-induced impacts is inappropriate since they are independent of Federal action, and could be nullified by actions of the State legislature or voters.

Our Response: In the case of the MSCP, an analysis of State-induced impacts is appropriate since the NCCP program is directly tied to the HCP through the terms of the MSCP Implementing Agreement. Though economic impacts associated with State and local actions were addressed in the draft economic analysis, the document clearly states that all impacts are assumed to be solely attributable to the Federal listing. Please refer to the draft economic analysis for further discussion of this issue.

Comment 16: One commenter expressed concern that the preface of the economic analysis acknowledges that the public believes that critical habitat designation could require additional project modifications, while the document later suggests in several instances that further modifications are not expected. The commenter suggests that the economic analysis provide further defense of this position and discuss specific regulation and policy in making the case.

Our Response: The statement in the preface of the economic analysis addresses public perception (also see the Stigma Effects section of the economic analysis) that critical habitat designation will present additional regulatory burden. The economic analysis effectively addresses these concerns by addressing the likelihood of an economic effect from the designation above and beyond the listing. The analysis correctly asserts that Deinandra conjugens critical habitat is occupied by either standing plants or seed bank, and correctly concludes that no additional project modifications are likely from the designation that would not have already been recommended to address the listed species and its habitat.

Comment 17: One commenter indicated that Dudleya variegata (variegated Dudleya) is not a State-listed species, as stated in the draft economic analysis. The commenter suggested that this statement leads to significant adjustments in the cost impacts within the economic analysis that should be corrected.

Our Response: Dudleya variegata is not a State-listed species. The species status has been addressed in the final addendum of the economic analysis. However, in this case, Dudleya variegata is a covered species under the MSCP Plan, and as such is treated similarly to both federally and State-listed species under the MSCP Plan. Therefore, adjustments in costs were correctly made to recognize the cost of measures intended to mitigate the effects of covered activities on Dudleya variegata under the MSCP Plan.

Comment 18: One commenter suggests that our “additional benefits” and “education/informational benefits” determinations were not substantiated, are arbitrary and capricious, and are based on litigation.

Our Response: In the Prudency Determination section of the proposed rule, we detailed our reasoning for determining that critical habitat is, in fact, prudent for Deinandra conjugens. In general, we concluded that there may be some additional benefits to designating critical habitat, including instances where section 7 consultation would be triggered only if critical habitat is designated, educational or informational benefits to designating critical habitat, and significant occurrences of Deinandra conjugens on Federal lands recorded since the time of listing.

Although we cannot substantiate in the present something that may occur in the future, critical habitat may provide some educational benefit by formally identifying areas within the range of Deinandra conjugens essential for the conservation of the species. The public and the Service would, therefore, benefit from the designation while planning any future recovery efforts for the species. Furthermore, three significant occurrences of Deinandra conjugens now occur on Federal lands, which were not known at the time of listing, substantiating the need to designate critical habitat on those lands. The benefit of the designation, in this case, is the added protections afforded by the relatively higher threshold of responsibility required of Federal agencies under section 7 the Act.

While we have acknowledged the potential for society to experience such benefits in our economic analyses for critical habitat rulemakings, our ability to actually measure these benefits in any meaningful way is difficult and imprecise at best. However, we will continue to explore ways that will allow us to provide more quantitative descriptions of the potential benefits associated with a critical habitat designation.

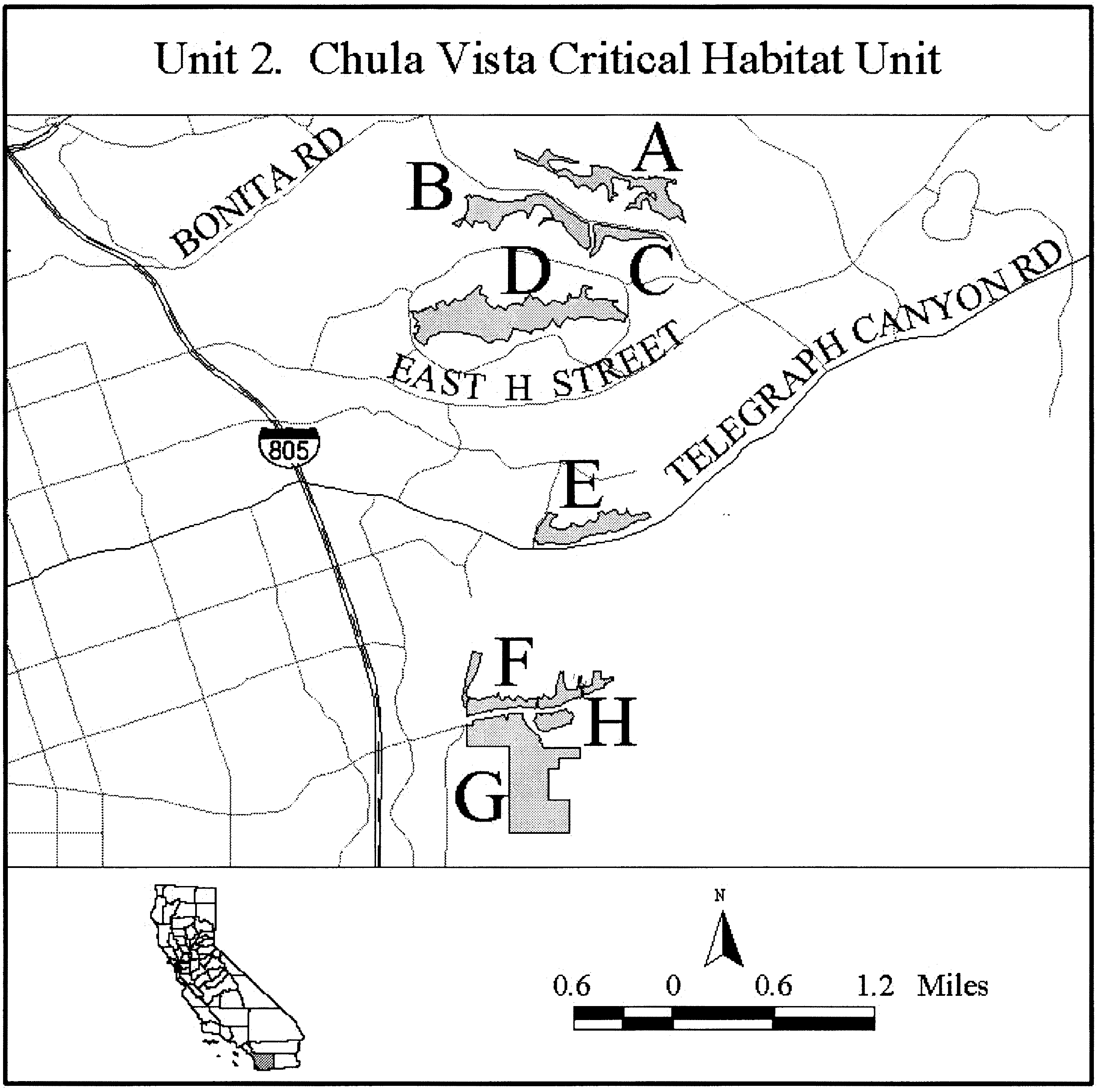

Summary of Changes From the Proposed Rule

In the development of our final designation of critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens, we considered new information provided to our office after the proposed designation was published. We made changes from our proposal based on a review of public comments received on the proposed designation and the draft economic analysis on the proposed designation and a re-evaluation of lands proposed as critical habitat. The refinements to the amount of land determined to be essential for Deinandra conjugens and incorporated into this final designation resulted in a net reduction of approximately 120 ha (300 ac) of lands. The primary changes for this final designation include the removal of 120 ha (300 ac) of lands from the development areas of the Eastlake Woods, Bella Lago and Rolling Hills Ranch residential developments, Sweetwater County Park Summit Site, and Sweetwater Authority lands, because these lands were determined not to be essential for the conservation of Deinandra conjugens.

In our proposed rule we identified certain lands within the proposed development projects of Bella Lago, Eastlake Woods, and Rolling Hills Ranch (all in the City of Chula Vista) that we believed contained primary constituent elements and standing plants or seed bank for Deinandra conjugens and included these as proposed critical habitat. Since the time of our proposal, we have reevaluated these areas and conclude that some of Start Printed Page 76038these lands do not contain the primary constituent elements for Deinandra conjugens and standing plants or seed bank, and are not essential for the long-term conservation of this species.

At the time of our proposed rule, rare plant surveys had not yet been completed on portions of the Bella Lago project site. Consequently, our boundaries for proposed critical habitat were based on general information concerning soils and vegetation. Surveys have since been completed and we have more current and definitive information relating to the location of Deinandra conjugens and the primary constituent elements essential to its conservation on the proposed project site. We have refined the boundaries of critical habitat in the southern portion of the project site to exclude approximately 5 ha (10 ac) that we now know do not contain the plant or its primary constituent elements. The remaining patches of land within the southern portion of the project site that contain occupied habitat and primary constituent elements are considered to be essential to the conservation of the species and are being designated as critical habitat.

Approximately 20 ha (55 ac) of the Eastlake Woods project site have also been deleted from the final critical habitat rule. Following the publication of the proposed rule, we completed a consultation with regard to Dienandra conjugens (and a conference with respect its proposed critical habitat) pursuant to section 7 of the Act with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) for the Eastlake Woods project, a residential development (1-6-02-FW-1989.2) in which we closely examined and evaluated the tarplant and its habitat on the project site. Based on the more thorough review of proposed critical habitat under the section 7 consultation for the Eastlake Woods neighborhood project, most of the areas being excluded as critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens are not habitat for this species, do not contain any known occurrences for this plant based on two years of surveys during the flowering season, and do not contain the primary constituent elements for this plant because of the extensive history of agricultural use. As a result of the consultation and conference opinion, an area of approximately 5 ha (10 ac) that had been proposed as critical habitat has been preserved, is being restored, and will receive long-term monitoring and management. This area is being retained as critical habitat. As a result of the consultation, 5 ha (10 ac) (an area that contained approximately 2,160 individual Deinandra conjugens in 2001) will be preserved onsite. The preserved area has broader conservation value because it adjoins areas conserved under the San Diego MSCP and the proposed Chula Vista Subarea Plan. Within the preservation area, approximately 2 ha (5 ac) will be restored to support approximately 870 plants. The entire area will be preserved and managed in perpetuity. These lands contain the plant and its primary constituent elements, are contiguous with critical habitat designated for the species on adjacent lands, and are considered to be essential to the conservation of the species. In our conference opinion we determined that development of the remaining 20 ha (55 acres) proposed as critical habitat for Dienandra conjugens would not result in adverse modification of this critical habitat unit. Approximately 20 ha (55 acres) were determined upon closer analysis not to be occupied by Dienandra conjugens nor contain primary constituent elements of its habitat. The inclusion of such areas in the proposed rule resulted from use of the 100-m UTM grid system which, as explained later in the rule, is not a fine enough scale to eliminate all areas that are not occupied or that do not contain primary constituent elements, and therefore do not meet the definition of critical habitat under 3(5)(A). Use of the 100-m grid resulted in the inclusion of lands under agricultural use for many years that were not known to be occupied by this species and that do not contain the primary constituent elements. Through the consultation and conference opinion we were able to identify these lands, and we concluded that development of the lands would not result in the adverse modification of proposed critical habitat. Thus, the areas excluded from critical habitat were not essential for the conservation for the species because the majority of these lands were not habitat for Deinandra conjugens, do not contain long-term conservation value, and/or do not contain primary constituent elements. The approximately 1 ha (2 ac) of remaining lands within the Eastlake Woods project did contain Dienandra conjugens and primary constituent elements. However, because the distribution of Dienandra conjugens in those areas was limited and restricted by active agricultural activity, we concluded they were not necessary for the conservation of this species and development of the lands would not result in adverse modification of proposed critical habitat. Upon the completion of the Section 7 consultation and conference opinions, the project proponent graded the 20 ha (55 acres) described above in preparation for development.

Portions of the Rolling Hills Ranch project site also have been excluded from final critical habitat. In April of 2001, prior to the publication of the proposed critical habitat rule, we were provided with current survey information for the Rolling Hills Ranch development project that indicated the presence of approximately 28,000 standing Deinandra conjugens plants scattered throughout the site. Following the publication of the proposed rule, we further evaluated this new occurrence information in the context of: (1) Other known occurrences throughout the range of the species; (2) the consultation on the Rolling Hills Ranch development project; and (3) the protections and conservation measures currently established in the approved San Diego MSCP and those measures proposed in the draft Chula Vista Subarea Plan for Deinandra conjugens.

Following this evaluation, we concluded that approximately 85 ha (215 ac) within the Rolling Hills project site are not essential to the conservation of Deinandra conjugens. At the time of the proposed rule, we used the 100-m UTM grid to identify critical habitat on portions of Rolling Hills Ranch, which resulted in designation of some areas that are not occupied by the species or that do not contain primary constituent. For the final rule, we have used the approved boundaries specific to the Rolling Hills Ranch project, thereby eliminating some areas that do not contain the plants or primary constituent elements for the species.

Furthermore, approximately 70 percent of the lands on Rolling Hills Ranch that have been deleted from the final rule on Rolling Hills Ranch are not known to contain standing occurrences of Deinandra conjugens. These lands may contain primary constituent elements and it is possible that they contain seed bank; however, the excluded areas are not known to support standing occurences of the species. Without better information that would substantiate the importance of these lands to the species, their conservation value cannot be determined. These lands are, therefore, not considered essential for the conservation of the species, and have been deleted from the final critical habitat rule.

Approximately 30 percent of the lands deleted from the final rule are considered to be occupied. We recently completed a consultation pursuant to section 7 of the Act with the Corps (1-6-01-F-1071.4), following an agreement Start Printed Page 76039reached among the Service, the California Department of Fish and Game, and the project proponent to modify the boundaries of proposed development, MSCP reserve, and MSCP Neutral areas on the project site. MSCP Neutral areas are those lands being conserved within the MSCP planning area, in this case by Rolling Hills Ranch, that are not covered lands under the MSCP. Pursuant to that agreement, project lands containing the most important occurrences of Deinandra conjugens and its primary constituent elements are designated as MSCP reserve and MSCP Neutral areas and will be protected, monitored, and managed for Deinandra conjugens. When identifying the areas set aside for conservation, we focused on conserving those occurrences that we believed to have the greatest chance of persistence within the project area. We concluded in our biological opinion that the loss of approximately 5 ha (10 ac) of occupied habitat would not result in the destruction or adverse modification of proposed critical habitat for the following reasons. First, the areas conserved would receive a higher level of management (e.g., invasive species control, monitoring and adaptive management of populations, etc.) compared to the no-project scenario. Without the project, the site was being used for agriculture and grazing, activities that would not be subject to regulations under the Act because of the absence of a federal nexus. As a result, there was a higher chance that the plant occurrences onsite would be degraded. The higher level of management within the conserved lands would ensure the long-term viability of the population in the area, thereby reducing the extent of land necessary to provide for the conservation of the species onsite. Second, the preserve design for Rolling Hills Ranch compliments regional conservation for Deinandra conjugens under the MSCP. As a result of this regional conservation planning, lands essential to the conservation of this species are being conserved and managed or are targeted for conservation and management. Finally, from a regional perspective, protection of all occupied habitat on the Rolling Hills Ranch project is not essential for the conservation of Deinandra conjugens; the limited loss of occupied habitat for this species at Rolling Hills Ranch will not preclude the recovery of this plant. We were able to utilize digital map data provided by Rolling Hills Ranch to refine critical habitat on the project site based on the modified boundary agreement. These lands to be protected on site contain the plant and its primary constituent elements, are contiguous with critical habitat designated for the species on adjacent lands, and are essential to the conservation of the species.

In addition, we refined the critical habitat boundaries for the final rule to exclude 5 ha (10 ac) of developed areas within the Sweetwater County Park Summit Site, and 5 ha (10 ac) of developed areas within Sweetwater Authority lands. These lands do not contain primary constituent elements for Deinandra conjugens, and are, therefore, not considered essential to the conservation of the species.

Also, the proposed rule indicated that 27,000 standing plants were located on Rolling Hills Ranch in year 2000. This number has been changed to 28,000 to correct a rounding error. Finally, the proposed rule indicated that critical habitat unit 2 encompasses approximately 521 acres, which we rounded to 520 acres for the final rule. No change in actual acreage for unit 2 was made in the final rule.

Finally, minor changes to the definition of primary constituent elements for Deinandra conjugens were also made to eliminate redundancy.

Critical Habitat

Critical habitat is defined in section 3 of the Endangered Species Act (Act), as amended, as—(i) the specific areas within the geographic area occupied by a species, at the time it is listed in accordance with the Act, on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protection; and (ii) specific areas outside the geographic area occupied by a species at the time it is listed, upon a determination that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. “Conservation” means the use of all methods and procedures that are necessary to bring an endangered species or a threatened species to the point at which listing under the Act is no longer necessary.

Critical habitat receives protection under section 7 of the Act through the prohibition against destruction or adverse modification of habitat with regard to actions carried out, funded, permitted, or authorized by a Federal agency. Section 7 of the Act also requires conference opinions on Federal actions that are likely to result in the destruction or adverse modification of proposed critical habitat. Aside from the added protection that may be provided under section 7, including adverse modification of habitat, the Act does not provide other forms of regulatory protection to lands designated as critical habitat. Further, consultation under section 7 of the Act does apply to activities on private or other non-Federal lands whenever a Federal nexus occurs.

In order to be included in a critical habitat designation, the habitat must be “essential to the conservation of the species.” Critical habitat designations identify, to the extent known and using the best scientific and commercial data available, habitat areas that are essential to the conservation of the species. Our regulations (50 CFR 424.12(e)) also state that, “The Secretary shall designate as critical habitat areas outside the geographic area presently occupied by a species only when a designation limited to its present range would be inadequate to ensure the conservation of the species.”

Section 4(b)(2) of the Act requires that we take into consideration the economic impact, and any other relevant impact, of specifying any particular area as critical habitat. We may exclude areas from critical habitat designation when the benefits of exclusion outweigh the benefits of including the areas within critical habitat, provided the exclusion will not result in extinction of the species.

Within the geographic area occupied by the species, we will designate only areas currently known to be essential. Essential areas should already have the features and habitat characteristics that are necessary to sustain the species. We will not speculate about what areas might be found to be essential if better information became available, or what areas may become essential over time. Within the geographic area occupied by the species, we will not designate areas that do not now have the primary constituent elements, as defined at 50 CFR 424.12(b), that provide essential life-cycle needs of the species.

Our Policy on Information Standards Under the Endangered Species Act, published in the Federal Register on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34271), provides criteria, establishes procedures, and provides guidance to ensure that our decisions represent the best scientific and commercial data available. It requires us, to the extent consistent with the Act, and with the use of the best scientific and commercial data available, to use primary and original sources of information as the basis for recommendations to designate critical habitat. When determining which areas are critical habitat, a primary source of information should, at a minimum, be the listing package for the species. Start Printed Page 76040Additional information may be obtained from a recovery plan, articles in peer-reviewed journals, conservation plans developed by States and counties, scientific status surveys and studies, biological assessments, unpublished materials, and expert opinion.

Section 4 of the Act requires that we designate critical habitat based on what we know at the time of the designation. Habitat is often dynamic, and species may move from one area to another over time. Furthermore, we recognize that designation of critical habitat may not include all of the habitat areas that may eventually be determined to be necessary for the recovery of the species. For these reasons, all should understand that critical habitat designations do not signal that habitat outside the designation is unimportant or may not be required for recovery. Areas outside the critical habitat designation will continue to be subject to conservation actions that may be implemented under section 7(a)(1) and to the regulatory protections afforded by the section 7(a)(2) jeopardy standard and the applicable prohibitions of section 9 of the Act, as determined on the basis of the best available information at the time of the action. Federally funded or assisted projects affecting listed species outside their designated critical habitat areas may still result in jeopardy findings in some cases. Similarly, critical habitat designations made on the basis of the best available information at the time of designation should not control the direction and substance of future recovery plans, habitat conservation plans, or other species conservation planning efforts if new information available to these planning efforts calls for a different outcome.

Methods

In determining areas that are essential to conserve Deinandra conjugens, we used the best scientific and commercial data available. We reviewed available information that pertains to the habitat requirements of this species, including data from research and survey observations published in peer-reviewed articles; regional GIS coverages (e.g., soils, known locations, vegetation, land ownership, and HCP boundaries); information from herbarium collections such as those from SDNHM; data from the CNDDB (2002); data collected from project-specific and other miscellaneous reports submitted to us; additional data from the San Diego County Multiple Species Conservation Program (MSCP), such as information from Subarea or draft Subarea HCPs (Subarea Plans) (e.g., City of San Diego, County of San Diego, City of La Mesa, and City of Chula Vista); information in the San Diego Gas and Electric HCP (1995); and a habitat evaluation model for the Otay Mesa Generating Project.

Primary Constituent Elements

In accordance with section 3(5)(A)(i) of the Act and regulations at 50 CFR 424.12, in determining which areas to designate as critical habitat, we must consider those physical and biological features (primary constituent elements) that are essential to the conservation of the species, and that may require special management considerations or protection. These include, but are not limited to: space for individual and population growth, and for normal behavior; food, water, air, light, minerals, or other nutritional or physiological requirements; cover or shelter; sites for pollination and germination or seed dispersal; and habitats that are protected from disturbance or are representative of the historical geographical and ecological distributions of a species. All areas designated as critical habitat for Deinandra conjugens are within the currently known range and contain one or more of these physical or biological features (primary constituent elements) essential for the conservation of the species.

The designated critical habitat is designed to provide sufficient habitat to maintain self-sustaining populations of Deinandra conjugens throughout its range, and provide those habitat components essential for the conservation of the species. Habitat components that are essential for Deinandra conjugens are found in vegetation communities classified as, but not limited to, grasslands, coastal sage scrub, or maritime succulent scrub in southwestern San Diego County, California. These habitat components provide for: (1) Individual and population growth, including habitat for germination, pollination, reproduction, pollen and seed dispersal, and seed dormancy; (2) areas that allow gene flow and provide connectivity or linkage between or within larger populations, including open spaces and disturbed areas that in some instances may also contain introduced plant species; (3) areas that provide basic requirements for growth such as water, light, and minerals; and (4) areas that support pollinators and seed dispersal organisms.