2014-15725. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for the Northwest Atlantic Ocean Distinct Population Segment of the Loggerhead Sea Turtle

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 39756

AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

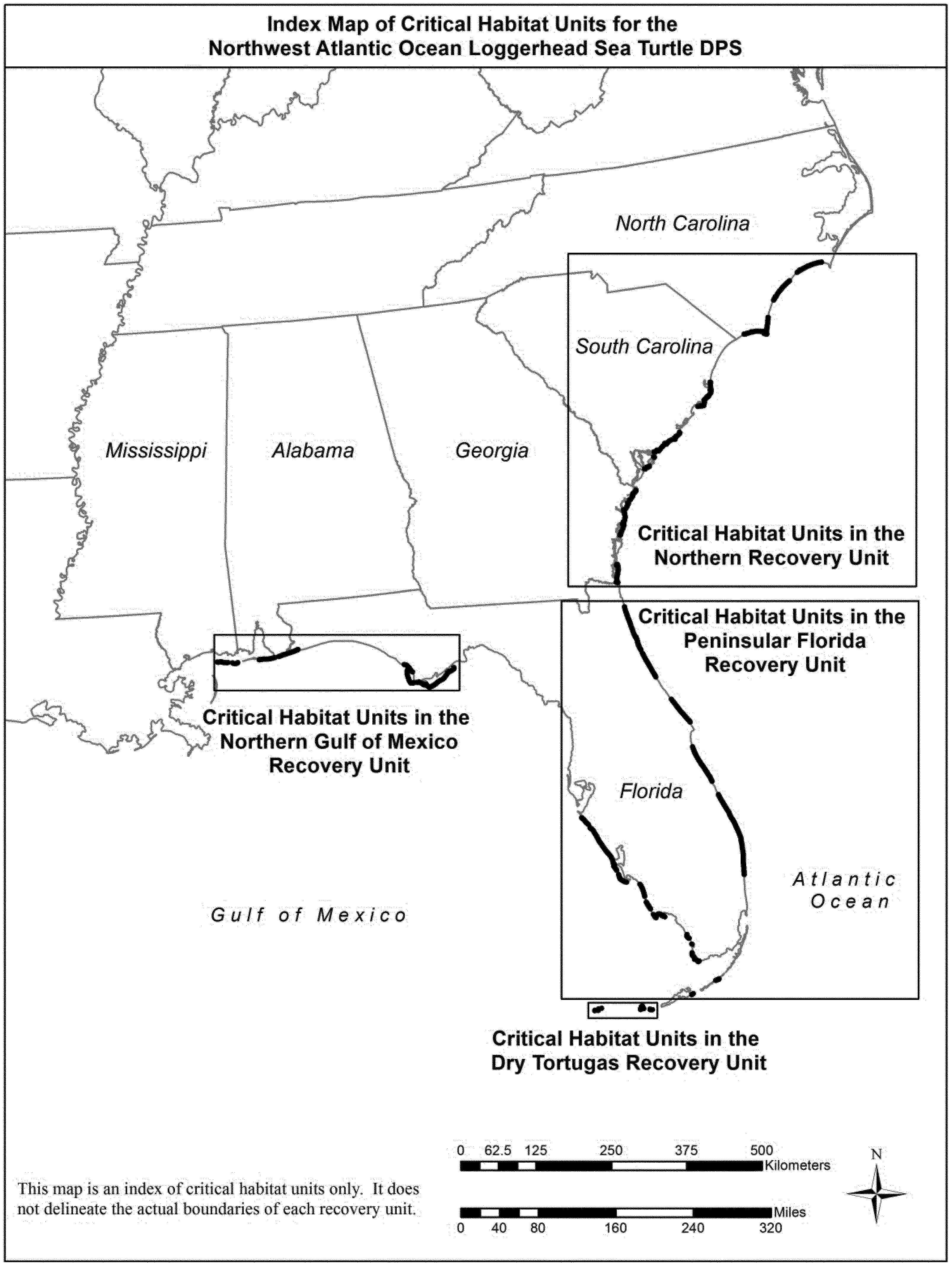

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, designate specific areas in the terrestrial environment of the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts as critical habitat for the Northwest Atlantic Ocean distinct population segment of the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended. In total, approximately 1,102 kilometers (685 miles) fall within the boundaries of the critical habitat designation.

DATES:

This rule is effective on August 11, 2014.

ADDRESSES:

This final rule and the associated final economic analysis are available on the Internet at http://www.regulations.gov and http://www.fws.gov/northflorida. Comments and materials we received, as well as supporting documentation we used in preparing this rule, are available for public inspection at http://www.regulations.gov. All of the comments, materials, and documentation that we considered in this rulemaking are available by appointment, during normal business hours at: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Florida Ecological Services Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT).

The coordinates, plot points, or both from which the maps are generated are included in the administrative record for this critical habitat designation and are available at http://www.fws.gov/northflorida,, at http://www.regulations.gov at Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2012-0103, and at the North Florida Ecological Services Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT). Any additional tools or supporting information that we developed for this critical habitat designation will also be available at the Fish and Wildlife Service Web site and Field Office listed above, and may also be included in the preamble of this rule and at http://www.regulations.gov.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

For general information about this rule, and information about the final designation in northeastern Florida, contact Jay B. Herrington, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Florida Ecological Services Office, 7915 Baymeadows Way, Suite 200, Jacksonville, FL 32256; telephone 904-731-3336; facsimile 904-731-3045. If you use a telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD), call the Federal Information Relay Service (FIRS) at 800-877-8339.

For information about the final designation in Alabama, contact Bill Pearson, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alabama Ecological Services Field Office, 1208 Main Street, Daphne, AL 36526; telephone 251-441-5181; facsimile 251-441-6222.

For information about the final designation in southern Florida, contact Craig Aubrey, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, South Florida Ecological Services Field Office, 1339 20th Street, Vero Beach, FL 32960; telephone 772-469-4309; facsimile 772-562-4288.

For information about the final designation in northwestern Florida, contact Catherine Philips, Acting Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Panama City Ecological Services Field Office, 1601 Balboa Avenue, Panama City, FL 32405; telephone 850-769-0552; facsimile 850-763-2177.

For information about the final designation in Georgia, contact Don Imm, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Coastal Georgia Ecological Services Field Office, 4980 Wildlife Drive NE., Townsend, GA 31331; telephone 912-832-8739; facsimile 912-832-8744.

For information about the final designation in Mississippi, contact Stephen Ricks, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Mississippi Ecological Services Field Office, 6578 Dogwood View Parkway, Suite A, Jackson, MS 39123; telephone 601-965-4900; facsimile 601-965-4340.

For information about the final designation in North Carolina, contact Pete Benjamin, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Raleigh Ecological Services Field Office, Post Office Box 33726, Raleigh, NC 33726; telephone 919-856-4520; facsimile 919-856-4556.

For information about the final designation in South Carolina, contact Thomas McCoy, Acting Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, South Carolina Ecological Services Field Office, 176 Croghan Spur Road, Suite 200, Charleston, SC 29407; telephone 843-727-4707; facsimile 843-727-4218.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. Under the Endangered Species Act (Act), when we determine that a species is endangered or threatened, we are required to designate critical habitat, to the maximum extent prudent and determinable. Designations of critical habitat can only be completed by issuing a rule. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or Service) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) listed the Northwest Atlantic Ocean distinct population segment (DPS) of the loggerhead sea turtle as threatened on September 22, 2011 (76 FR 58868). The USFWS and NMFS share jurisdiction under the Act for the protection and conservation of sea turtles, including the loggerhead. USFWS has jurisdiction over sea turtles on the land; NMFS has jurisdiction over sea turtles in the water.

This rule consists of: A final rule designating areas in the terrestrial environment as critical habitat for the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS of the loggerhead sea turtle. NMFS will be designating areas in the marine environment as critical habitat for the DPS and, consistent with their distinct authority with respect to such areas, will designate such areas in a separate rulemaking. In this rule, “critical habitat” refers to the areas we are designating in the DPS's terrestrial environment unless otherwise specified.

The areas we are designating in this rule constitute our current best assessment of the areas that meet the definition of critical habitat for the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS of the loggerhead sea turtle. We are designating:

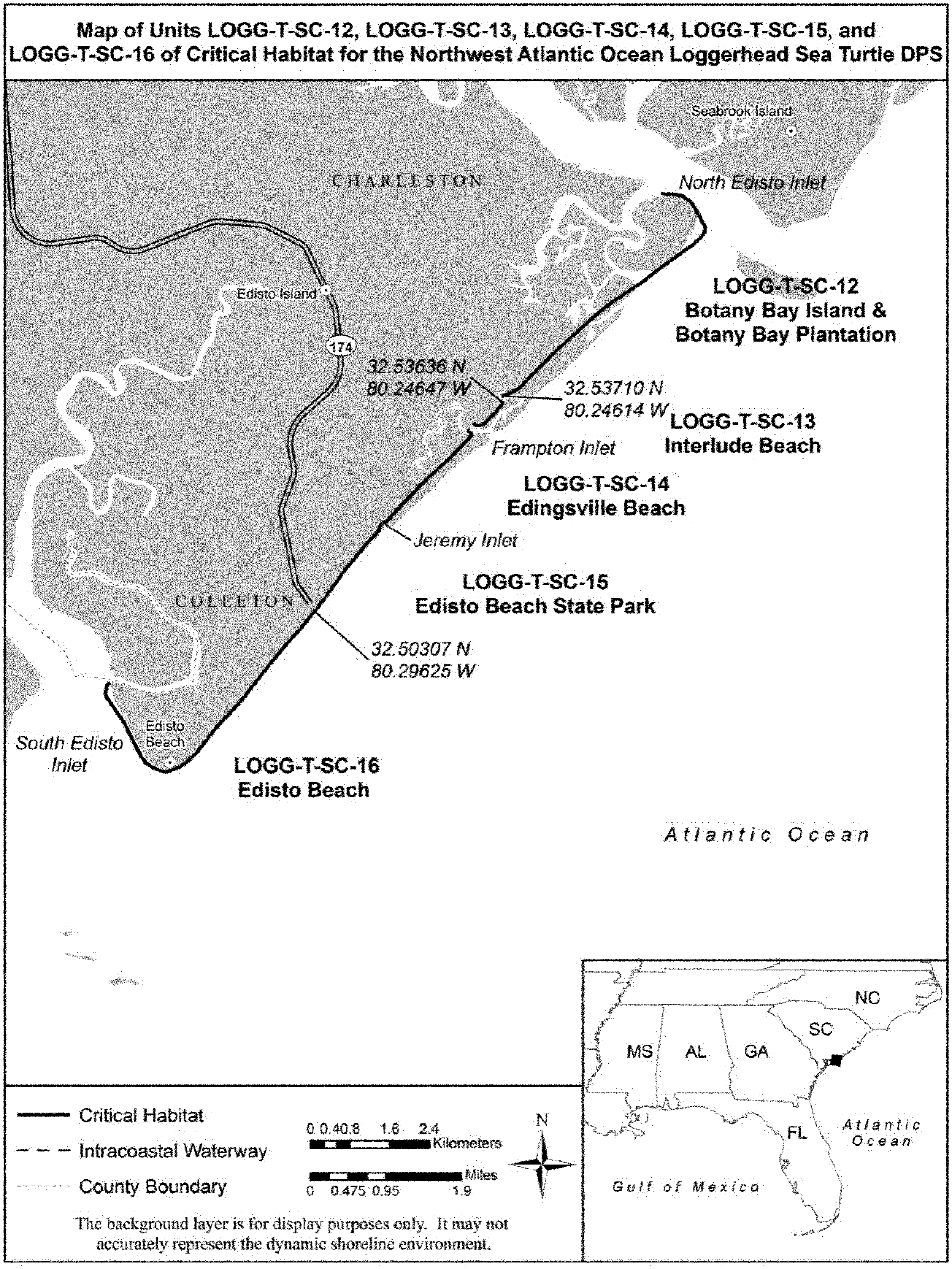

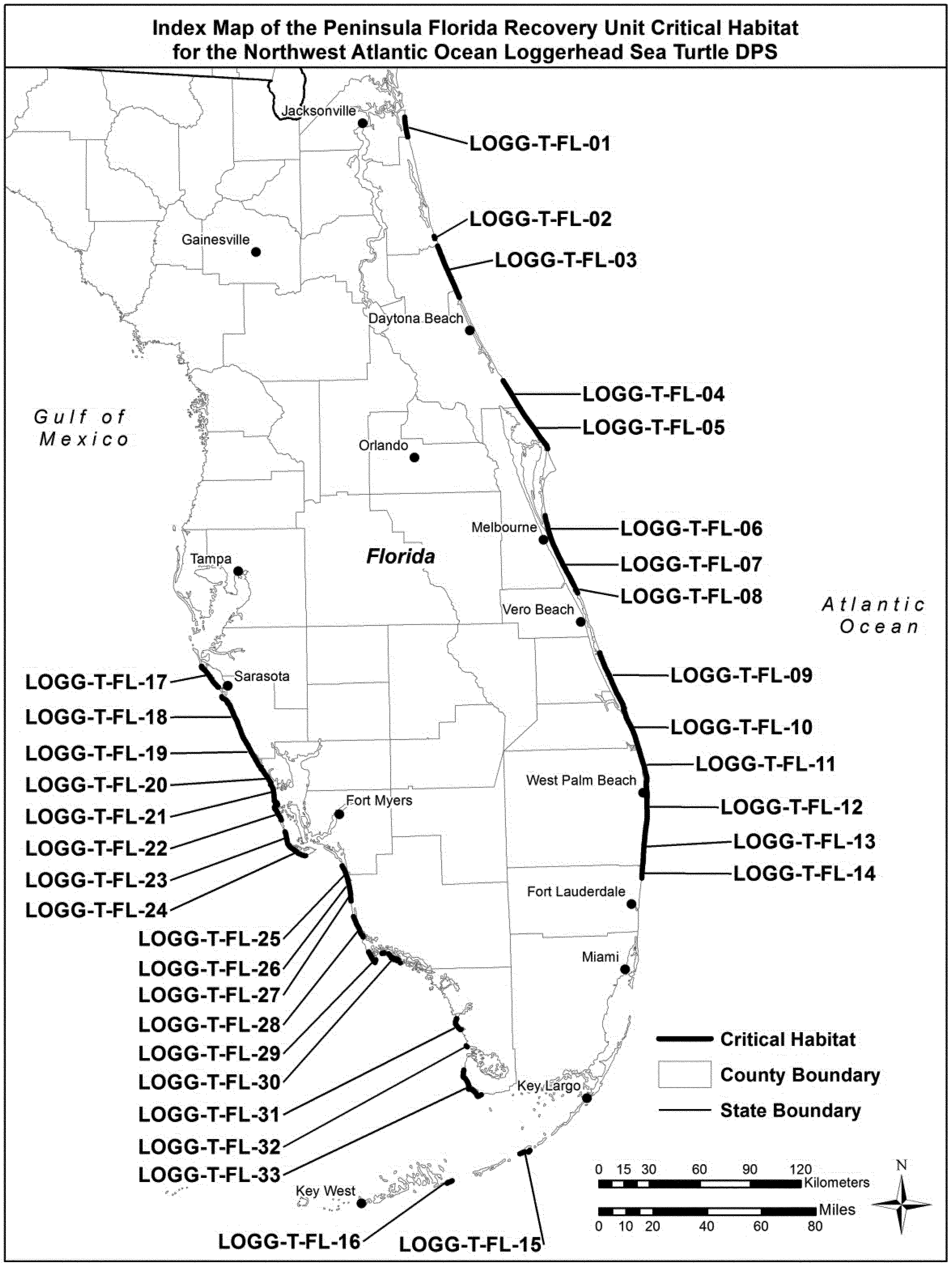

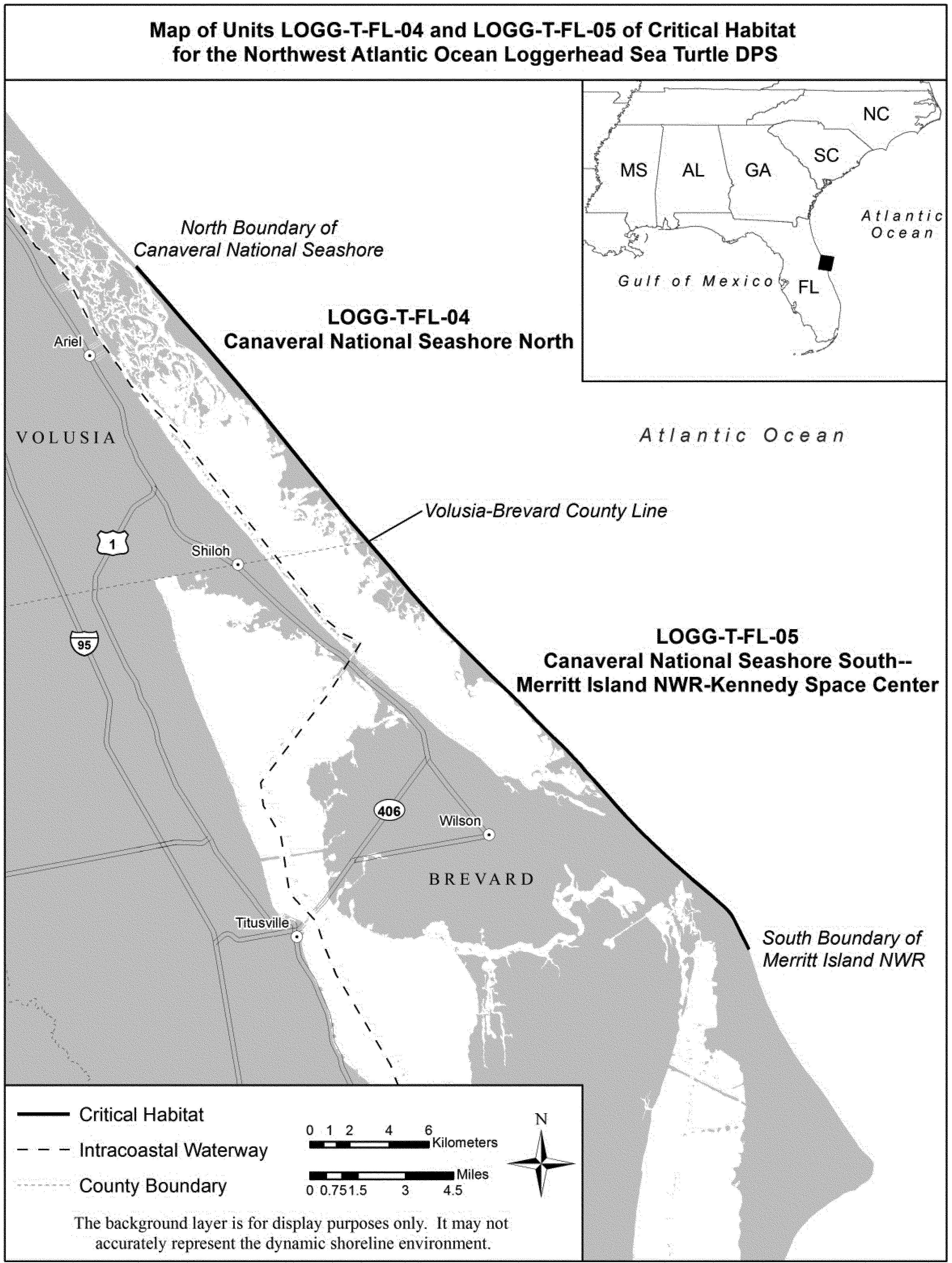

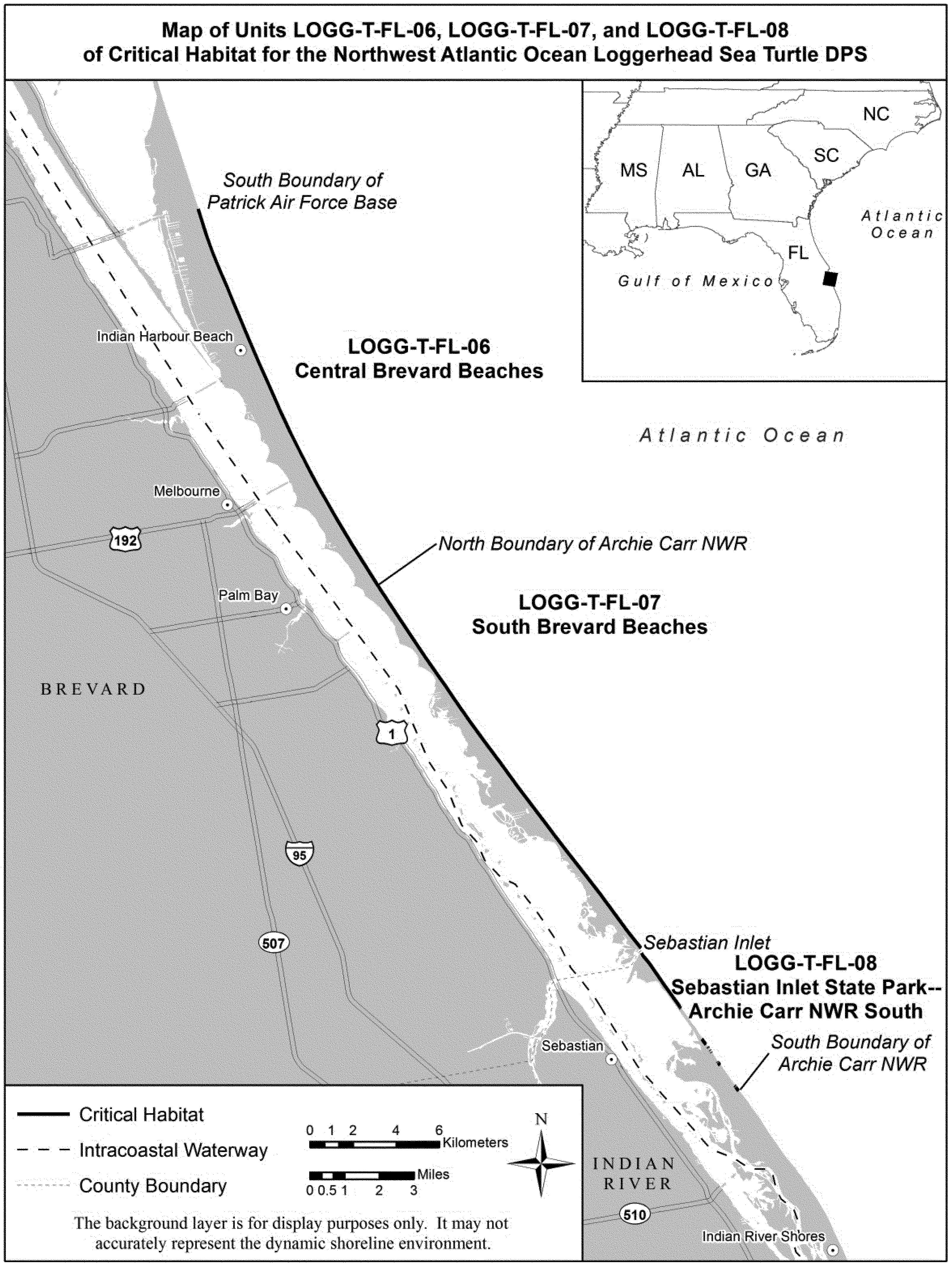

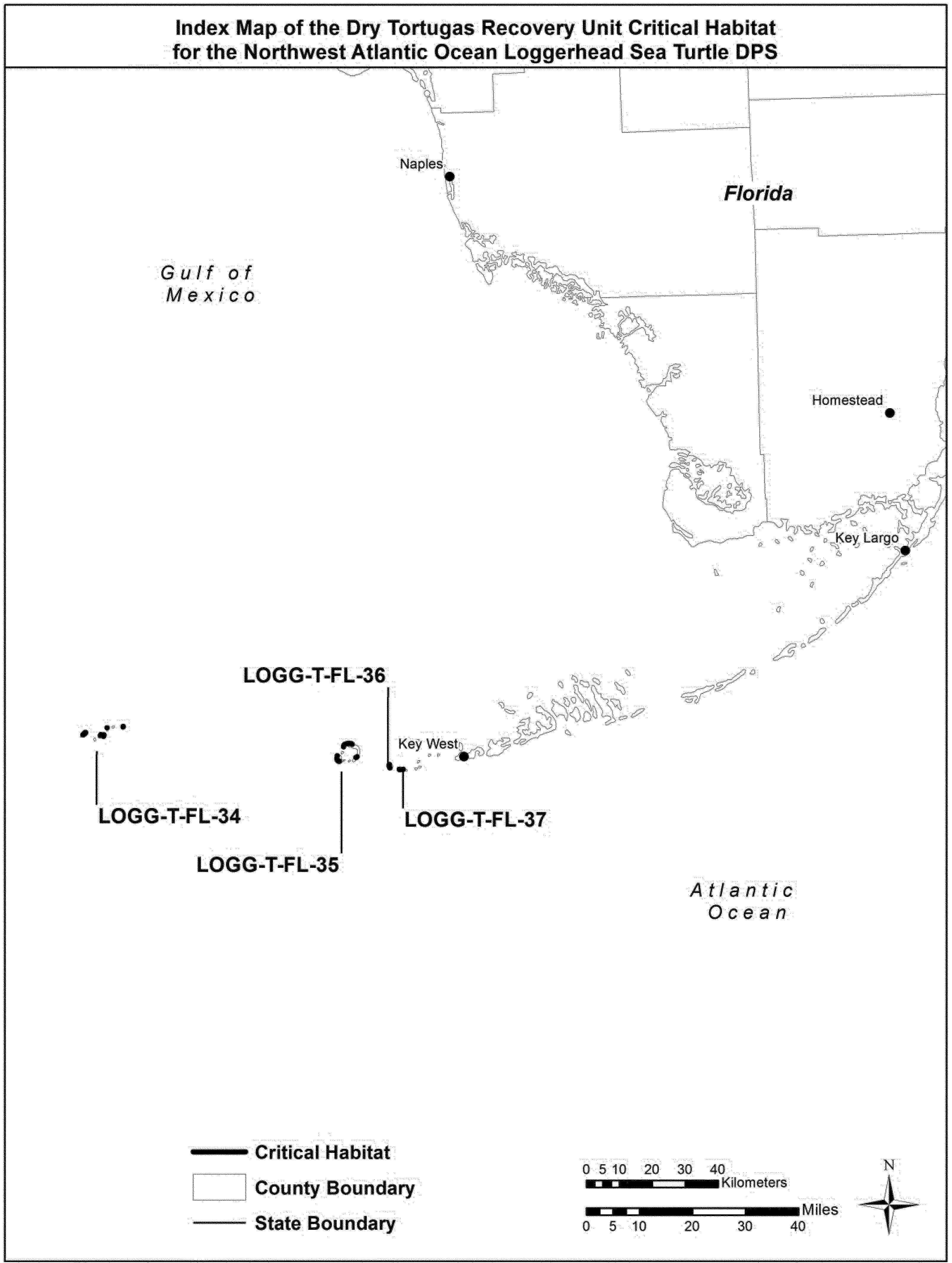

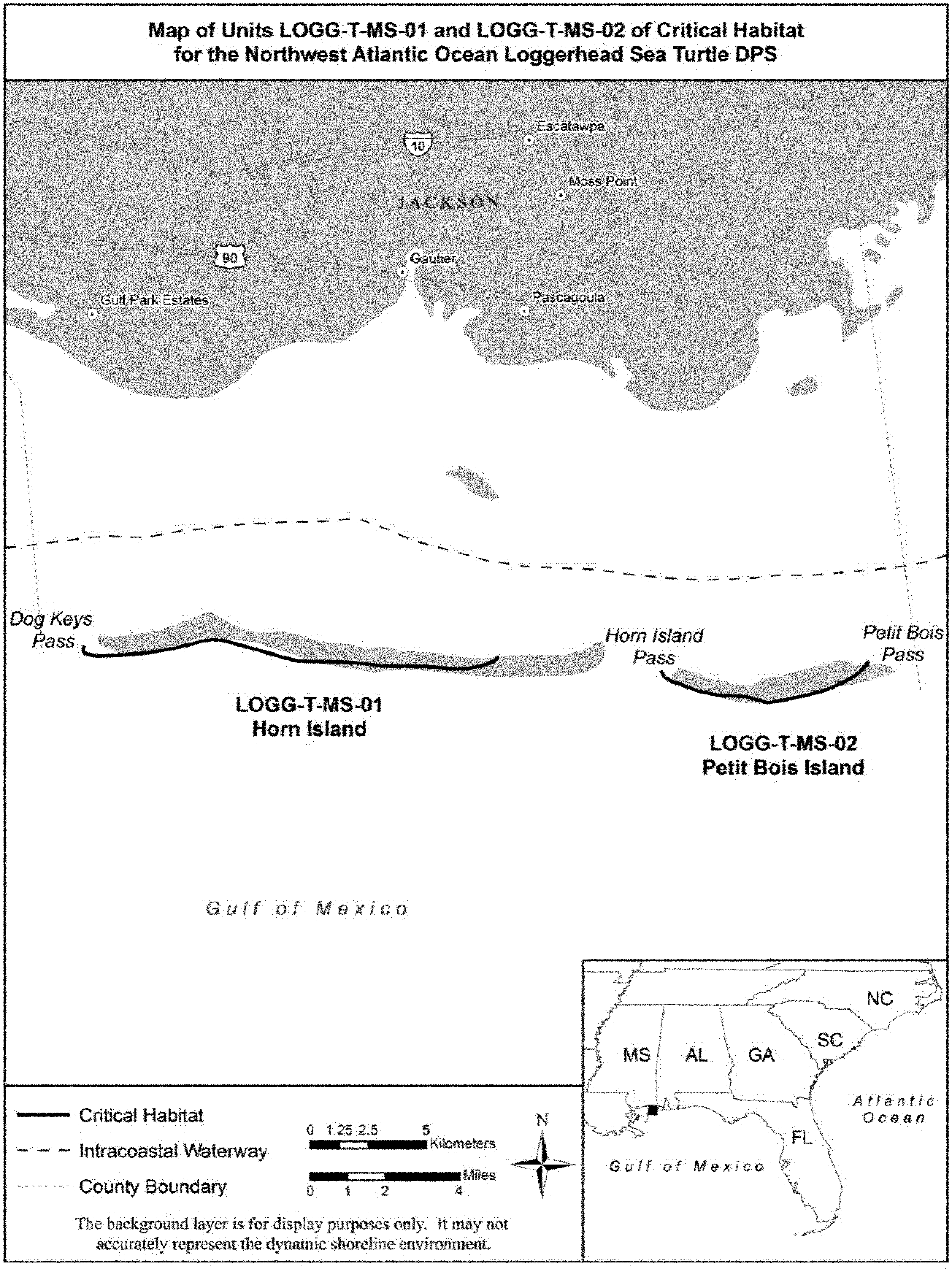

- In total, approximately 1,102 kilometers (km) (685 miles (mi)) of loggerhead sea turtle nesting beaches as critical habitat in the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. These beaches account for 45 percent of an estimated 2,464 km (1,531 mi) of coastal beach shoreline and approximately 84 percent of the documented nesting (numbers of nests) within these six States. The critical habitat is located in Brunswick, Carteret, New Hanover, Onslow, and Pender Counties, North Carolina; Beaufort, Charleston, Colleton, and Georgetown Counties, South Carolina; Camden, Chatham, Liberty, and Start Printed Page 39757McIntosh Counties, Georgia; Bay, Brevard, Broward, Charlotte, Collier, Duval, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gulf, Indian River, Lee, Manatee, Martin, Monroe, Palm Beach, Sarasota, St. Johns, St. Lucie, and Volusia Counties, Florida; Baldwin County, Alabama; and Jackson County, Mississippi.

- We are exempting the following Department of Defense (DOD) installations from critical habitat designation because their integrated natural resources management plans (INRMPs) incorporate measures that provide a benefit for the loggerhead sea turtle: Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune (Onslow Beach), North Carolina, and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Patrick Air Force Base, and Eglin Air Force Base (Cape San Blas), Florida.

- Under section 4(b)(2) of the Act, we are excluding from critical habitat designation areas in St. Johns, Volusia, and Indian River Counties, Florida, that are covered under a habitat conservation plan (HCP), because the Secretary finds that the benefits of excluding these areas outweigh the benefits of including them in the critical habitat designation.

- We are not excluding any additional areas from critical habitat based on economic, national security, or other relevant impacts.

We have prepared an economic analysis of the designation of critical habitat. In order to consider economic impacts under 4(b)(2) of the Act, we prepared an economic analysis of the critical habitat designations and related factors. We announced the availability of the draft economic analysis (DEA) in the Federal Register on July 18, 2013 (78 FR 42921), and sought comments from the public. We have incorporated the comments and have completed the final economic analysis (FEA) concurrently with this final determination.

Peer review and public comment. We sought comments from four independent specialists to ensure that our designation is based on scientifically sound data and analyses. We requested opinions from these four knowledgeable individuals on our technical assumptions, analysis, and whether or not we had used the best available information. We received responses from three of the peer reviewers. These peer reviewers concurred with our methods and conclusions, and provided additional information, clarifications and suggestions to improve this final rule. Information we received from peer review is incorporated in this final designation. We also considered all comments and information received from the public during the two comment periods and three public hearings.

Previous Federal Actions

Please refer to the final rule revising the loggerhead sea turtle's listing from a single worldwide threatened species to nine DPSs, published in the Federal Register on September 22, 2011 (76 FR 58868), for a detailed description of previous Federal actions concerning this species and protection under the Act.

Summary of Comments and Recommendations

We requested written comments from the public on the proposed designation of critical habitat for the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS of the loggerhead sea turtle during two comment periods. The first comment period opened with the publication of the proposed rule on March 25, 2013 (78 FR 17999), and closed on May 24, 2013. The second comment period, during which we requested comments on the proposed critical habitat designation and associated draft economic analysis (DEA), opened on July 18, 2013 (78 FR 42921), and closed on September 16, 2013. We held three public hearings in August 2013: Wilmington, North Carolina; Morehead City, North Carolina; and Charleston, South Carolina. We also contacted appropriate Federal, State, county, and local agencies; scientific organizations; and other interested parties and invited them to comment on the proposed rule and the DEA during these comment periods.

During the first comment period, we received 19,969 comment letters addressing the proposed critical habitat designation. The majority of these comments were form letters and letters with multiple signatures. During the second comment period, we received 2,206 comment letters addressing the proposed critical habitat designation, the DEA, or both. The majority of these comments were also form letters and letters with multiple signatures. Comments on the proposed critical habitat rule were also submitted to NMFS during the comment period for its proposed designation of critical habitat in the marine environment for the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS. During the three public hearings held on August 6, 7, and 8, 2013, 47 individuals or organizations made comments on the proposed designation or DEA. Comments received were grouped into general issues specifically relating to the proposed designation. These and other substantive information are addressed in the following summary and incorporated into the final rule as appropriate.

Peer Reviewer Comments

In accordance with our peer review policy published on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34270), we solicited expert opinion from four knowledgeable individuals with scientific expertise that included familiarity with the loggerhead sea turtle and its terrestrial habitat, biological needs, and threats. We received responses from three of the peer reviewers.

We reviewed all comments we received from the peer reviewers for substantive issues and new information regarding the proposed designation. The peer reviewers generally concurred with our methods and conclusions, and provided additional information, clarifications, and suggestions to improve this final critical habitat rule. Peer reviewer comments are addressed in the following summary and incorporated into the final rule as appropriate.

(1) Comment: One peer reviewer commented on the justification for our proposed exemption of military installations and exclusion of areas with existing habitat conservation plans (HCPs), emphasizing the importance of all areas to the recovery of the species.

Our Response: The USFWS acknowledges that all nesting beaches support the conservation and recovery of the species. All areas including military installations and areas with existing HCPs were evaluated according to the selection criteria. Section 4(a)(3)(B)(i) of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533(a)(3)(B)(i)) was amended in 2004 through the National Defense Authorization Act of 2004 (Pub. L. 108-136) to provide that: “The Secretary shall not designate as critical habitat any lands or other geographic areas owned or controlled by the Department of Defense, or designated for its use, that are subject to an integrated natural resources management plan prepared under section 101 of the Sikes Act (16 U.S.C. 670a), if the Secretary determines in writing that such plan provides a benefit to the species for which critical habitat is proposed for designation.”

The USFWS analyzed the INRMPs developed by military installations located within the range of the proposed critical habitat designation for the loggerhead sea turtle to determine if they would meet the exemption criteria under section 4(a)(3) of the Act. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Patrick Air Force Base, and Eglin Air Force Base are DOD lands with completed INRMPs that provide benefits to the loggerhead sea Start Printed Page 39758turtle. Accordingly, we are exempting those areas from the designation.

Regarding areas with existing HCPs, per section 4(b)(2) of the Act the Secretary may exclude an area from critical habitat if she determines that the benefits of such exclusion outweigh the benefits of specifying such area as part of the critical habitat, unless she determines, based on the best scientific data available, that the failure to designate such area as critical habitat will result in the extinction of the species. In making that determination, the statute, as well as the legislative history is clear that the Secretary has broad discretion regarding which factor(s) to use and how much weight to give to any factor. The USFWS conducted this analysis on the areas with existing HCPs and did decide to exclude three areas covered by HCPs. We provide additional details later in this final rule (see Exclusions section).

(2) Comment: One peer reviewer commented on the availability of recent study results, ongoing work, and information on loggerhead sea turtles.

Our Response: The final rule has been updated as appropriate throughout the document with the new information.

(3) Comment: One peer reviewer commented on the difficulty to assess the analysis and assumptions without the specific datasets available in the proposed rule.

Our Response: As stated in the proposed rule, all supporting documentation, such as the nesting densities used in the critical habitat selection process, were available during the open comment periods for the proposed rule and are currently available for public inspection on http://www.regulations.gov,, or by appointment, during normal business hours, at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Florida Ecological Services Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT).

General Comments Provided by Multiple Commenters

(4) Comment: A number of Federal and State agencies, local municipalities, and several other commenters expressed concern about the economic impacts of the critical habitat designation.

Our Response: As described in Section 2.3.2 of the FEA, it is unlikely that the critical habitat designation will result in additional management efforts resulting from future section 7 consultations with the USFWS. Nesting loggerhead turtles, their nests, eggs, and hatchlings, as well as any of their nesting habitat not designated as critical habitat, are still protected under the Act regardless of whether or not critical habitat is designated. They receive protection via section 7 where they may be the subject of conservation actions and regulatory protection, ensuring Federal agency actions do not jeopardize their continued existence, and via section 9, which prohibits “take” of individuals, including take caused by actions that affect the DPS' habitat. Take can only be authorized through the processes provided in sections 7 and 10 of the Act, and their implementing regulations. In the FEA, we considered whether additional or different conservation measures would be needed to avoid destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat above and beyond those measures already needed to avoid jeopardizing the continued existence of the species, and found this to be unlikely. As a result, the quantified direct incremental impacts of the designation are expected to be limited to additional administrative costs to the USFWS, Federal agencies, and third parties of considering critical habitat as part of future section 7 consultations. These costs are borne by the USFWS, the Federal action agency, and the third-party participants (generally the project proponents), including State and local governments and private parties. In the areas proposed as critical habitat designation, these costs were estimated to total approximately $1,200,000 over the next 10 years ($160,000 annualized).

In addition, the FEA acknowledges that, in some cases, critical habitat may generate indirect impacts including costs associated with project delay due to third-party litigation against the USFWS or the Federal action agency and the increased length of time it will take for the USFWS to review projects. Forecasting the likelihood of third-party litigation and potential length of associated project delays is considered too speculative to be quantified in the FEA. However, delays attributable to the additional time to consider critical habitat as part of future section 7 consultations, if any, would most likely be minor. This is because potential impacts to critical habitat are considered at the same time as impacts to the species.

(5) Comment: A number of commenters expressed concern that areas outside of the critical habitat designation will receive less protection.

Our Response: A critical habitat designation does not signal that habitat outside the designated area is unimportant or may not support the conservation of the species. Areas that are important to the conservation of the species, both inside and outside the critical habitat designation, may continue to be the subject of conservation actions implemented under section 7(a)(1) of the Act. Turtles in those areas are subject to the regulatory protections afforded by the requirement in section 7(a)(2) of the Act for Federal agencies to ensure their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species, and section 9 of the Act's prohibitions on taking any individual of the species, including take caused by actions that affect habitat. Take can be authorized only through the processes provided in sections 7 and 10 of the Act, and their implementing regulations.

Federal Agency Comments

(6) Comment: The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) commented that the proposed rule does not provide additional protection to loggerheads within the limits of the Kennedy Space Center's (KSC) coastline and that KSC meets the exemption criteria since NASA implements comprehensive conservation and habitat management plans that incorporate measures that provide a benefit for the conservation of the loggerheads.

Our Response: Unlike DOD lands with approved INRMPs, there is no categorical exemption under the Act for areas with other types of habitat management plans.

(7) Comment: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) expressed concern that the critical habitat designation will financially impact congressionally authorized projects and associated dredging activities for ports, navigation channels, and coastal storm damage reduction projects. Their concern extends to increased timeframes for consultations.

Our Response: As described in section 2.3.2 of the FEA, it is unlikely that the critical habitat designation will result in additional management efforts resulting from future section 7 consultations with the USFWS. The USFWS considered whether additional or different conservation measures would be needed to avoid destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat above and beyond those measures needed to avoid jeopardizing the continued existence of the species, and found this to be unlikely. As outlined in our response to Comment (4), designation of critical habitat delays attributable to the additional time to consider critical habitat as part of future section 7 consultations, if any, would most likely be minor. Also, see our response to Comment (4), and the Economic Impacts portion of this rule, below, for a Start Printed Page 39759discussion of indirect impacts associated with critical habitat designation.

(8) Comment: The USACE expressed concern that if operation and maintenance dredging projects were determined to adversely modify critical habitat, it could result in substantial economic consequences. The USACE believes that these projects should be identified as “manmade structures” and excluded from critical habitat designation. The USACE's responsibility is to maintain safe and adequate configurations and depths for commercial and recreational navigation, national defense, safety and refuge, and national economic development. “Excluding” these congressionally authorized projects will enable USACE to fulfill is responsibilities efficiently and effectively.

Our Response: We considered the economic impact, national security impact, and any other relevant impact of designating as critical habitat areas with projects that occur within operation and maintenance areas. In evaluating whether any such areas should be excluded due to economic impacts, we concluded that no change in economic activity levels or the management of economic activities, including dredging projects, is expected to result from the critical habitat designation. A key conclusion of the analysis is that the listing of the DPS may lead to additional conservation efforts that would not have been required otherwise. However, as outlined in our response to Comment (4), designation of critical habitat is not anticipated to generate additional conservation measures for the DPS beyond those generated by the species' listing. Section 7 consultation is required in occupied habitat with or without a critical habitat designation. Most of the forecast costs reflect additional administrative effort as part of future section 7 consultations in order to consider the potential for activities to result in adverse modification of critical habitat. That having been said, we acknowledge it is unlikely additional conservation measures beyond those identified to avoid jeopardy for the DPS would be required to avoid adverse modification.

State Agency Comments

Section 4(i) of the Act states: “the Secretary shall submit to the State agency a written justification for his failure to adopt regulations consistent with the agency's comments or petition.” The designation of critical habitat for the DPS includes beaches in the States of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Comments from the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and Mississippi regarding the proposal to designate critical habitat for the loggerhead sea turtle are addressed below.

(9) Comment: A number of States, State agencies, and municipalities believe that USFWS should undergo a consistency determination under the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA; 16 U.S.C. 1451 et seq.) for the proposed designation of critical habitat in each State that has a CZMA program.

Our Response: The USFWS has determined that the designation of critical habitat does not require a consistency review under CZMA. Federal agencies are responsible for ensuring that consistency review under CZMA is completed as needed for each action they fund, authorize, or carry out. The designation of critical habitat is not a “Federal agency activity” as defined in the CZMA implementing regulations at 15 CFR 930.31(a), but rather an establishment of Federal agency responsibility related to the conservation of federally protected endangered or threatened species. Thus, the designation is not an agency activity itself, but results in a requirement that Federal agencies ensure that any action they fund, authorize, or carry out is not likely to result in the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitat of any endangered or threatened species. Therefore, while we understand the commenters' position, the Service has determined that consistency review is not needed.

(10) Comment: The North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources (NCDNER) disagrees with the USFWS' assessment that “designation of critical habitat in areas currently occupied by the loggerhead sea turtle may impose nominal additional regulatory restrictions to those currently in place and, therefore, may have little incremental impact on State and local governments and their activities.” Similarly, while the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC) understands there is large uncertainty regarding “special management considerations” or additional protections that may ensue from the critical habitat designation, it expresses concern that such management considerations or protections may have far-reaching consequences that could reduce or restrict the effectiveness of the robust conservation measures already in place and may affect the public's ability to access and use existing public trust resources, including beaches and waterways. These agencies, as well as several other commenters, believe the USFWS should clarify the potential range of additional management efforts, regulatory reviews, and/or operational conditions that may be placed upon those activities listed as “threats” to designated critical habitats.

Our Response: Section 7(a)(2) of the Act and its implementing regulations at 50 CFR part 402 require Federal agencies to consult with the USFWS to ensure that they are not undertaking, funding, permitting, or authorizing actions likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed species or destroy or adversely modify designated critical habitat. Only projects that have a Federal nexus (e.g., projects that are funded, authorized, or carried out by Federal agencies) are subject to this requirement under section 7 consultation. The designation of critical habitat does not affect land ownership or establish a refuge, wilderness, reserve, preserve, or other conservation area. Such designation does not allow the government or public to access private land and does not require implementation of restoration, recovery, or enhancement measures by non-Federal parties. Where the States, local communities, or a landowner requests Federal agency funding or authorization for an action that may affect a listed species or critical habitat, the consultation requirements of section 7 would apply, but even in the event of a destruction or adverse modification finding, the obligation of the Federal action agency and the non-Federal party is not to restore or recover the species, but to implement reasonable and prudent alternatives to avoid destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat.

We identified 12 categories of threats that may require special management considerations or protection in the proposed critical habitat units. Most, if not all, of these threats already undergo special management considerations by Federal action agencies and have done so since the loggerhead sea turtle was initially listed in 1978. There are a number of options for management efforts determined to be necessary and will be considered on a unit by unit basis. Operational conditions can be incorporated into a project description or permit conditions to avoid or minimize these threats. However, the determination of which measure or combination of measures will depend on the site conditions; nature of the proposed action; duration and magnitude of potential impacts from the project; conservation measures already in place; and other site- and action-specific considerations. If additional Start Printed Page 39760measures are determined to be necessary, they will be considered in order to minimize the impacts to the listed DPS and the nesting beach. Critical habitat will not, as noted in our proposed designation, change the consultation process (see also response to Comment (4)), nor would it likely make it more difficult to move a project forward within an area designated as critical habitat, or conversely make it easier to do so on nesting beaches outside such a designation.

We do not expect the designation of critical habitat to result in changes to how the conservation efforts are currently implemented. Our proposal to designate critical habitat did not reflect an assessment that current nesting beach sea turtle conservation efforts are insufficient. Quite the opposite is true. Our focus is on those locations with the greatest nesting densities and, therefore, highest conservation value to loggerhead recovery and conservation. Most of the beaches proposed for designation have active sea turtle conservation efforts by Federal, State, local governments; private conservation organizations; and individuals within coastal communities.

(11) Comment: The NCDNER and North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission (NCCRC) recommend that the USFWS prepare a comprehensive economic analysis of the potential impacts to coastal communities and stakeholders as a result of the additional management efforts the designation may require.

Our Response: The Service's focus on the incremental impacts of the critical habitat rule is consistent with the U.S. Office of Management and Budget's (OMB's) guidelines for best practices concerning the method of conducting an economic analysis of Federal regulations. As described in section 2.1 of the FEA, OMB guidelines direct Federal agencies to measure the costs of a regulatory action against a baseline, which it defines as the “best assessment of the way the world would look absent the proposed action.” The baseline utilized in the FEA is the existing regulatory and socio-economic burden imposed on landowners, managers, or other resource users potentially affected by the designation of critical habitat absent the designation of critical habitat. The baseline includes protections afforded the species under the Act, as well as under other Federal, State, and local laws and guidelines.

In recognition of the divergent opinions of the courts and to address the Presidential memorandum dated February 28, 2012, the Service promulgated final regulations specifying that the impact analysis of critical habitat designations should focus on incremental effects (78 FR 53058; August 28, 2013). This regulation now codifies the process of impact analysis for proposed critical habitat by completing an “incremental analysis.” This method of determining the probable impacts of the designation seeks to identify and focus solely on the impacts over and above those resulting from existing protections.

Accordingly, the FEA employs “without critical habitat” (baseline) and “with critical habitat” (incremental) scenarios. The analysis qualitatively describes how baseline conservation efforts for the DPS may be implemented across the proposed designation, and, where possible, provides examples of the potential magnitude of costs of these baseline conservation efforts (Chapter 3). The FEA focuses, however, on the incremental analysis, describing and monetizing the incremental impacts due specifically to the designation of critical habitat for the DPS (Chapter 4). Sections 2.2 and 2.3 of the FEA describe in detail how the analysis defines and identifies incremental effects of the proposed designation.

The incremental approach employed by the Service in its analyses of proposed critical habitat designations does not necessarily limit impacts to administrative costs of consultation. In some cases designation of critical habitat does result in new project modifications that need to be implemented to avoid possible adverse modification of the habitat. The costs of these project modifications would then be counted in the incremental analysis, regardless of who incurs the cost. In the case of the DPS, the entire proposed critical habitat is occupied by the species, and therefore any project modifications will be required even absent critical habitat (i.e., in the baseline) to avoid possibly jeopardizing the species' existence (see response to Comment (4)).

(12) Comment: The NCDNER and NCCRC believe the USFWS should provide additional information on the data utilized for the proposed designations in North Carolina.

Our Response: Supporting documentation we used in preparing the proposed and final rules, as well as comments and materials we received during the two public comments periods, is available for public inspection on http://www.regulations.gov,, or by appointment, during normal business hours, at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Florida Ecological Services Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT).

(13) Comment: The South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism recommends language used in the proposed rule be refined to address all ambiguities and more clearly specify and define permissible and non-permissible activities in order to avoid unnecessary legal disputes. Specifically, in the sections pertaining to Special Management Considerations or Protection, the language is often ambiguous or vague, leaving it open to interpretation. For example, the language used for activities listed as primary threats, especially coastal development and beach renourishment, needs to be more clearly specified in terms of activity definitions and circumstances in order to prevent any party from using this rule change to unnecessarily impede non-threatening activities through legal action. These types of delays can ultimately drive up costs for ongoing beach preservation efforts and negatively impact local communities and their economies. In addition, in the aftermath of a severe tropical storm or hurricane, this language may be used to prevent rebuilding previously existing structures on public beaches such as Edisto Beach, effectively shutting off the beach for public use. Similarly, in the section regarding “Human Presence,” while the majority of this section pertains to human presence at night, the statement referring to human foot traffic may also be interpreted to mean that protecting these habitats necessitates the removal of all human presence, regardless of time.

Our Response: The USFWS has revised the language in this final rule to clarify the discussion and description of Special Management Considerations or Protection and threats to critical habitat.

(14) Comment: South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) notes an apparent lack of clarity as to what critical habitat designation means. The agency is uncertain of the actual impact to properties titled to the State of South Carolina and would like further clarification as to what changes would occur if such designation is finalized and accepted.

Our Response: See our response to Comment (10), above.

(15) Comment: The Mississippi Development Authority commented that the reasoning for critical units along the shoreline of Mississippi was not apparent as there are far fewer nests compared to the southeast coast of Florida. They questioned the Start Printed Page 39761significance of the two Mississippi units to the conservation of the species.

Our Response: We understand that the beaches in Mississippi have lower nesting densities than in some of the other parts of the DPS's nesting range. The beaches that met the critical habitat criteria not only had the highest nesting densities within each of the four recovery units, but also represented a good spatial distribution that will help ensure the protection of genetic diversity, and collectively provide a good representation of total nesting. The distribution of designated critical habitat will conserve the habitat of this DPS by:

- Maintaining their existing nesting distribution;

- Allowing for movement between beach areas depending on habitat availability (response to changing nature of coastal beach habitat) and supporting genetic interchange;

- Allowing for an increase in the size of each recovery unit to a level where the threats of genetic, demographic, and normal environmental uncertainties are diminished; and

- Maintaining their ability to withstand local or unit level environmental fluctuations or catastrophes.

(16) Comment: The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) commented that to provide more regulatory certainty, it would be helpful if the USFWS would provide details on what standards will be used to determine if a project will result in adverse modification. Some Florida stakeholders have expressed concern regarding the uncertainty of how this designation affects the section 7 review and approval process. To that end, FWC requests additional details on how the USFWS' section 7 consultation process will differ in areas that are designated as critical habitat as compared to those areas that are not designated. The FWC believes the USFWS should consider the effects of the designation of critical habitat on the State's ability to restore and maintain sandy beaches and maintain functioning inlets.

Our Response: Federal action agencies, in coordination with the USFWS, will assess each project during the section 7 consultation process to determine whether the project may adversely modify the designated critical habitat (see Effects of Critical Habitat Designation). These determinations generally are project specific and dependent on the conservation measures incorporated in the project design. For some projects, such as sand placement and groin and jetty repair and replacement, the USFWS has determined that the terms and conditions incorporated in the Florida Statewide Programmatic Sand Placement Biological Opinion for the DPS and other listed species would also ensure that sand placement projects, including emergency response, would not adversely modify critical habitat. See also our response to Comments (4) and (10).

(17) Comment: The FWC recommends further coordination between the USFWS and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) to avoid unintended consequences of the proposed critical habitat designation and existing State rules. In particular, current Florida law allows for the installation of coastal armoring protecting beachfront dwellings and infrastructure at risk to high frequency storms. However, the FDEP, through Florida Administrative code rule 62B-41.0055, prohibits coastal armoring in any location that is federally designated as critical habitat for sea turtles. As such, if the proposed critical habitat is established, the State may need to consider revising this rule.

Our Response: The USFWS is aware of the State regulation and is willing to work with the FDEP to provide any additional information needed regarding impacts to loggerhead sea turtles. If the State of Florida rescinds the regulation, the USFWS will also work with any Federal agency that may fund, construct, or authorize a coastal armoring project and to determine the need to undergo section 7 consultation.

Public Comments

General

(18) Comment: Several commenters, many from municipalities within proposed critical habitat units, requested that the USFWS extend the comment period to allow sufficient time to provide comments that balance the environmental and economic effects of the proposed rule.

Our Response: After the close of the initial comment period, the USFWS reopened the comment period for an additional 60 days on July 18, 2013 (78 FR 42921), with the announcement of the availability of the DEA of the proposed rule. We also held three public hearings to accept comments following announcement and reopening of the comment period.

(19) Comment: The USFWS should make its final determination of loggerhead critical habitat on nesting beaches in conjunction with the NMFS designation in the marine environment. There is concern that the independent actions of the agencies may result in inconsistent designations that do not reflect the importance of the connection between the marine and terrestrial environments.

Our Response: Although the proposed rules for critical habitat in the terrestrial and marine environments were not published at the same time, the USFWS and NMFS have been coordinating our efforts and sharing information throughout the rulemaking process. The agencies will continue to do so, and it is anticipated that the final rules for critical habitat in both the terrestrial and marine environments will be published, and become effective, simultaneously.

(20) Comment: USFWS' failure to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) in connection with designating critical habitat is a violation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA; 42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq.), as designation of critical habitat significantly affects the quality of the human environment.

Our Response: It is our position that, outside the jurisdiction of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, we do not need to prepare environmental analyses pursuant to the NEPA in connection with designating critical habitat under the Act. See the Required Determinations section of the rule below for more about USFWS's position.

(21) Comment: The USFWS should provide a detailed description of additional regulatory requirements associated with the planning, implementation, and maintenance of shoreline and inlet projects within the critical habitat area designation.

Our Response: The USFWS does not anticipate any additional regulatory requirements associated for any inlet or shoreline projects within the critical habitat units over and above those that would be required for the listed DPS (see our response to Comment (4)).

(22) Comment: The USFWS should provide a complete assessment of existing sea turtle management efforts by local, State, and Federal jurisdictions (including the USACE) affected by the proposed critical habitat designation area.

Our Response: Within each critical habitat unit description, the USFWS identifies conservation or management plans that benefit the loggerhead sea turtle. We also identify specific sea turtle management efforts conducted on public lands as identified in the Federal, State and local management plans within that critical habitat unit. If a Federal agency is conducting, funding, or authorizing a project in the unit, we will, during section 7 consultation, include in the biological opinion terms Start Printed Page 39762and conditions as appropriate to minimize the impacts of the project.

(23) Comment: The USFWS should conduct an analysis as to whether assumptions used in the Statewide Programmatic Biological Opinion (SPBO) covering the state of Florida, including the reasonable and prudent measures, are truly satisfactory to avoid adverse modification of critical habitat.

Our Response: The USFWS used the most updated information in the SPBO to minimize the impact of the sand placement projects on the loggerhead sea turtle and other listed species. Our responsibility for analysis of impacts includes the nesting beach. Since the listed sea turtle species must use the nesting beach for laying their nests, incubating their eggs, and the emergence and movement of hatchlings from the nest to the ocean, the terms and conditions in our SPBO also address minimizing impacts to the nesting beach. As the beaches designated as critical habitat are all nesting beaches, these terms and conditions will also minimize impacts to critical habitat.

Economic Impacts

(24) Comment: The Town of Edisto Beach, South Carolina, requests that the USFWS withdraw the rule or eliminate the prohibitions due to significant adverse economic effects.

Our Response: With regard to the commenter's reference to “prohibitions,” we clarify that the 12 activities described in the rule as primary threats do not equate to prohibitions of the continued and future implementation of such activities. These primary threats are categories of activities that may impact the habitat and may require special management considerations or protection. However, this rule designating critical habitat does not dictate what those special management or protection measures will be. Rather, such measures will be considered project specific and will depend on the measures already in place or incorporated into proposed projects, and the potential impacts of a proposed Federal action (or an action that is funded or permitted by a Federal agency) to the critical habitat. We have revised the language in the Special Management Considerations or Protection section of this final rule to clarify this.

In addition, the DEA did not indicate that there would be significant economic effects from the proposed designation (see our response to Comment (4)).

(25) Comment: There are economic impacts to creating loggerhead habitat in the Gulf of Mexico shoreline of Florida. With the regional biological opinion for hopper dredging in the Gulf, communities and the USACE are able to dredge and restore beaches in Florida during the summer months. There is a prohibition of summer dredging elsewhere (in order to protect turtles). If critical habitat is designated, it is not clear if summer construction will be permitted to continue. Thus greater competition for dredges during the winter will occur and result in an increase in prices for shore protection efforts.

Our Response: The regional biological opinion, which was prepared by NMFS to cover the offshore (marine) dredging portion of beach nourishment projects, includes terms and conditions intended to minimize impacts to sea turtles and other listed species in the Gulf of Mexico. Additionally, the USFWS' SPBO covers the onshore (terrestrial) portion of beach nourishment and also includes measures to minimize impacts of the sand placement on the nesting beach on sea turtles and other listed species. Neither set of terms and conditions is expected to change as a result of critical habitat designation because, due to the presence of the listed species, the required terms and conditions are expected to also avoid adverse modification of critical habitat.

Exclusions

(26) Comment: The USFWS should minimize exclusions from critical habitat. Although economic impacts must be considered, the ultimate designation decision must be based on the biological and physical needs of the species and not economics. The commenter encourages the USFWS to fully consider the economic benefits of loggerhead critical habitat designation, including the tourism benefits of sea turtle habitat protection.

Our Response: We are required by section 4(b)(2) of the Act to take into account national security, economic, and other relevant impacts of critical habitat designation. The Secretary may exclude an area from critical habitat if she determines that the benefits of such exclusion outweigh the benefits of specifying such area as part of the critical habitat, unless she determines, based on the best scientific data available, that the failure to designate such area as critical habitat will result in the extinction of the species. In making that determination, the statute on its face, as well as the legislative history, are clear that the Secretary has broad discretion regarding which factor(s) to use and how much weight to give to any factor.

The primary goal of this critical habitat designation for the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS of the loggerhead sea turtle is to support its long-term conservation and recovery. Conservation and recovery of the DPS may result in benefits, including use benefits (wildlife-viewing), non-use benefits (existence values), and ecosystem service benefits (e.g., water quality improvements and enhanced habitat conditions for other species). In this rule, the economic analysis did evaluate such benefits of the proposed critical habitat designation but was unable to monetize their value. Since we do not anticipate that critical habitat designation will change the level or types of conservation efforts undertaken over and above those efforts already required for the listed species, we have no information on the incremental benefits that may be realized. Absent information on the incremental change in loggerhead population or recovery potential associated, we are unable to monetize associated incremental use and non-use benefits.

When identifying the benefits of exclusion, we consider, among other things, whether exclusion of a specific area is likely to result in conservation; the continuation, strengthening, or encouragement of partnerships; or implementation of a management plan. The exclusions we identified in the proposed critical habitat rule were based on the presence of HCPs. When we evaluate the existence of a conservation or management plan when considering the benefits of exclusion, we consider a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, whether the plan is finalized; how it provides for the conservation of the essential physical or biological features; whether there is a reasonable expectation that the conservation management strategies and actions contained in a management plan will be implemented into the future; whether the conservation strategies in the plan are likely to be effective; and whether the plan contains a monitoring program or adaptive management to ensure that the conservation measures are effective and can be adapted in the future in response to new information.

(27) Comment: A number of commenters believe that the USFWS should not exclude six of the proposed units (numbered in the proposed rule as LOGG-T-FL-01, LOGG-T-FL-02, LOGG-T-FL-03, LOGG-T-FL-04, LOGG-T-FL-05, and LOGG-T-FL-10 in St. Johns, Volusia, and Indian River Counties, Florida) pursuant to section 4(b)(2) of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533(b)(2)). The proposed rule identified these units Start Printed Page 39763as being considered for exclusion based on the rationale that they are covered by HCPs (78 FR 18000; March 25, 2013). Two commenters believe that although the HCPs are commendable, case law does not support this basis for exclusion (e.g., Cape Hatteras Access Pres. Alliance v. U.S. Dep't of Interior, 731 F. Supp. 2d 15, 28 (D.D.C. 2010), quoting Natural Res. Def. Council, 113 F.3d at 1127: “. . . the [Act] does not authorize `nondesignation of habitat when designation would be merely less beneficial to the species than another type of protection' ”). Mandatory consultation for Federal actions is a valuable benefit for the species. Additionally, HCPs expire over time and are vulnerable to cut-backs. Many commenters believe that protections in the areas covered by HCPs are inadequate. For example, the St. Johns County HCP only covers beach driving; it does not include or protect against all the possible dangerous activities that occur on these beaches.

Commenters further state that unlike DOD lands with approved INRMPs, there is no categorical exemption under the Act for areas with HCPs and there is no indication that the Secretary similarly has determined in writing that such a plan provides a benefit to the species for which critical habitat is proposed for designation. Because these plans can change over time, and assuming they meet the necessary biological criteria, all such areas should be included in the designation of critical habitat.

Our Response: Using information collected during the public comment periods, as well as the HCP's annual reports and information already in our files, we evaluated whether these or other lands in the proposed critical habitat were appropriate for exclusion from this final designation pursuant to section 4(b)(2) of the Act. We evaluated whether the benefits of excluding the particular area outweigh the benefits of their inclusion, based on the “other relevant factor” provisions of section 4(b)(2) of the Act.

We find that the St. Johns, Volusia, and Indian River Counties' HCPs meet the above criteria for exclusion. Therefore, we are excluding non-Federal lands covered by these HCPs in proposed Units LOGG-T-FL-01, LOGG-T-FL-02, LOGG-T-FL-03, LOGG-T-FL-04, LOGG-T-FL-05, and LOGG-T-FL-10 because those HCPs adequately provides for the long-term conservation of the loggerhead and the Secretary has determined that the benefits of excluding these areas outweigh the benefits of including them in critical habitat. (For further information, see Exclusions, below.)

(28) Comment: Indian River County should be included in the designation of critical habitat, including currently unoccupied habitat, because a portion of the Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge occurs in the County. According to NMFS' Web site (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/loggerhead.htm), this refuge provides habitat for 25 percent of nesting loggerheads in the United States.

Our Response: As discussed above (see our response to Comment (27)), non-Federal lands in Indian River County are covered by a county-wide HCP and are being excluded from critical habitat. However, a portion of Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge, which is located in Indian River County but not within the HCP, is included in the critical habitat (Units LOGG-T-FL-07 and LOGG-T-FL-08).

Recommendations for Expansion of Critical Habitat Designation

(29) Comment: The USFWS must expand its proposal to include all areas containing the primary constituent elements that are essential to the conservation of the species. The USFWS's methodology of selecting the top 25 percent nesting density beaches and those adjacent to them does not appear to designate all areas occupied by the species on which the biological features essential to the conservation of the species are present. The USFWS must explain how its selection of more limited areas satisfies this legal requirement and provides for the conservation and recovery of the species.

Our Response: Section 3(5)(C) of the Act states that “[e]xcept in those circumstances determined by the Secretary, critical habitat shall not include the entire geographical area which can be occupied by the . . . species.” Further, the USFWS is not required to designate all areas on which physical or biological features supporting the species are found. An area occupied by the species at the time of listing is eligible for designation of critical habitat if it contains “physical and biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protection” (section 3(5)(A)(i) of the Act).

All terrestrial units considered for designation as critical habitat are currently occupied by the loggerhead sea turtle and occur within the species' geographical range. They contain the physical and biological features essential to the conservation of the species and may require special management considerations or protection, and they contain the primary constituent elements sufficient to support the terrestrial life-history processes of the species sufficient for the conservation of the population. Of these beaches, the ones we designated are those that have the highest nesting densities within each of the four recovery units, have a good spatial distribution that will help ensure the protection of genetic diversity, and collectively provide a good representation of total nesting. The beaches adjacent to the primary high-density nesting beaches also currently support loggerhead nesting and can serve as expansion areas should the high-density nesting beaches be significantly degraded or temporarily or permanently lost through natural processes or upland development. Thus, the amount and distribution of critical habitat we are designating for terrestrial habitat will conserve recovery units of this DPS as described in our response to Comment (15).

(30) Comment: The USFWS should consider designation of areas that would provide for resilience to the threat of climate change, especially sea level rise and increased temperatures. The USFWS should consider sea level rise and its effects on the loggerhead sea turtle. While accounting for the level of sea rise is a complex task, there is a broad consensus in the scientific community that sea level rise is imminent. This will pose a significant threat to the beaches the loggerhead sea turtles need for continuation of the species.

Our Response: As the comment acknowledges, specific forecasts related to climate change are difficult. Furthermore, habitat is dynamic, and nesting beaches may accrete and erode over time. We recognize that critical habitat designated at a particular point in time may not include all of the habitat areas that we may later determine are necessary for the recovery of the species. For these reasons, a critical habitat designation does not signal that habitat outside the designated area is unimportant or may not support the conservation of the species. Areas that are important to the conservation of the species, both inside and outside the critical habitat designation, may continue to be the subject of conservation actions, regulatory protections, and prohibitions on taking of the species, including taking caused by actions that affect habitat. The USFWS acknowledges that we cannot fully address the significant, long-term threat of climate change to Start Printed Page 39764loggerhead sea turtles. However, we can determine how we respond to the threat of climate change by providing protection to the known nesting sites of the turtle. We can also identify measures to protect nesting turtles and their habitat from the actions (e.g., coastal armoring, sand placement) undertaken to respond to climate change that may potentially impact the DPS. As more specific forecasts become available in the future, a revision of critical habitat may be required to more effectively provide for the conservation of the species. At this time, however, such forecasts are unavailable. For more information on our assessment of climate change, see the Climate Change discussion within the of the Special Management Considerations or Protection section of this rule.

(31) Comment: Broward County Natural Resource Planning and Management Division and several other commenters believe that all or portions of Broward County should be considered for inclusion in the designation of critical habitat. Large areas of sea turtle nesting habitat exist in the County, particularly in the Fort Lauderdale, Dania Beach, North Hollywood Beach, and Hallandale areas. There is considerable nesting activity for the beaches between Hillsboro Inlet and Port Everglades. With a few exceptions (e.g., Port Everglades), the coastline has the appropriate physical and biological features as well as the primary threats requiring management. For example, in 2012, a volunteer organization in the County documented 20,000 disoriented hatchlings.

Commenters believe that Broward County should be listed as critical habitat because Florida has the most nesting habitat in the world for loggerhead sea turtles, which makes this area extremely important. Furthermore, beach nourishment is allowed to continue through May, which is both mating and nesting season for this species. Due to over-development of the coastal areas, the dunes have been removed, causing more beach erosion. Lastly, designation of critical habitat will help facilitate quicker compliance with the lighting laws and will ensure all future lights are up to code; critical habitat designation will help bring the County under one universal lighting code, which will help with enforcement.

Our Response: The USFWS acknowledges the importance of the beaches in Broward County, including Fort Lauderdale, Dania Beach, North Hollywood Beach, and Hallandale Beach. However, only Unit LOGG-T-FL-14—Boca Raton Inlet-Hillsboro Inlet in Palm Beach and Broward Counties met the selection criteria (see our responses to Comments (15) and (29), above), with a nesting density greater than 83 nests per kilometer. The adjacent beach selected to serve as an expansion area for this unit is Unit LOGG-T-FL-13—Boyton Inlet-Boca Raton Inlet in Palm Beach County. Other nesting beaches in Broward County did not meet the critical habitat selection criteria because the nesting density was not high enough. However, loggerhead sea turtle nesting along these beaches will continue to be protected, as the DPS is listed as threatened under the Act and Federal agencies are required to consult with the USFWS to ensure that they are not undertaking, funding, permitting, or authorizing actions likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed species.

(32) Comment: The USFWS should consider beaches from Doctor's Pass to Gordon Pass and Marco Island in Collier County, Florida, and the eastern end of Sanibel Island in Lee County, Florida, for inclusion in critical habitat. While these beaches are not the same nesting density as other beaches proposed for designation, they are currently occupied and do appear to contain the physical and biological features and PCEs. They have suitable nesting habitat that has relatively unimpeded access (PCE 1), appropriate sands to allow for nest building (PCE 2), and, when existing sea turtle protection ordinances are observed, sufficient darkness (PCE 3). Additionally, these beaches have supported considerable nesting and would support the USFWS's goal of designating beaches for resiliency and redundancy.

Our Response: The USFWS acknowledges the importance of the beaches in Lee and Collier Counties. However, only Unit LOGG-T-FL-28—Keewaydin Island and Sea Oat Island from Gordon Pass to Big Marco Pass in Collier County met the selection criteria (see our responses to Comments (15) and (29) above) with a nesting density greater than 14.2 nests per km. The adjacent beach selected to serve as an expansion area for this unit is Unit LOGG-T-FL-27—Clam Pass to Doctors Pass in Collier County. Other nesting beaches in Lee and Collier Counties, such as the east end of Sanibel Island and Marco Island, did not meet the critical habitat selection criteria because the nesting density was not high enough. However, the loggerhead sea turtle nesting along these beaches will continue to be protected, as the DPS is listed as threatened under the Act and consultation between Federal action agencies and the USFWS is still required.

(33) Comment: Additional areas should be designated as critical habitat for Georgia. Specifically, the commenter recommends inclusion of Little St. Simons and Jekyll islands in critical habitat.

Our Response: These beaches (Little St. Simons and Jekyll islands) did not meet the critical habitat selection criteria because the nesting density was not high enough (greater than 11.34 nests per km) or the island was not adjacent to a high density nesting beach. The beaches that are being designated as critical habitat represent over 80 percent of loggerhead sea turtle nesting in Georgia based on nest monitoring data from 2006 to 2011 provided by the State of Georgia.

(34) Comment: A few comments encourage the USFWS to expand the designation areas in North Carolina and include more habitat in the designation. One comment suggests that the USFWS considers other factors as well as those described in the proposed rule, such as those listed as PCEs (e.g., unimpeded near-shore access located above mean high water mark, suitable sand, and suitable nesting beach habitat). Alternatively, the USFWS could broaden the habitat by selecting the top 50 percent of high-density areas instead of adding beaches based on adjacency. The commenter also recommends that additional areas be designated as critical habitat for South Carolina. Specifically, the commenter recommends inclusion of the following beaches and islands: Bay Point, Hilton Head, North, Pritchards, Bull, and Hunting.

Similarly, other comments recommend the inclusion of Cape Hatteras, Cape Lookout, Figure 8 Island, Ocean Isle, and Sunset Beach, North Carolina. They maintain that focusing on areas of greatest nest density per kilometer of beach ignores larger areas such as Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout National Seashores, which have the highest total number of nests per beach in North Carolina.

Another comment asked that areas to the north of Bogue Banks, North Carolina, be designated, as nesting is anticipated to increase in the north both due to warming and range expansion expected with an increasing population.

Our Response: The USFWS acknowledges the importance of all loggerhead sea turtle nesting beaches. The recommended beaches did not meet the critical habitat selection criteria either because the nesting density was not high enough (greater than 2.38 nests per kilometers in North Carolina; greater than 13.97 nests per kilometer in South Start Printed Page 39765Carolina) or the island was not adjacent to a high density nesting beach. The selected high density beaches and adjacent beaches represent over 75 and 96 percent of loggerhead nesting in North Carolina and South Carolina, respectively, based on data from 2006-2011. Loggerhead nests will continue to be protected along beaches that are not designated as critical habitat because the DPS is listed as threatened under the Act (see our responses to Comments (15) and (29), above).

(35) Comment: It is important that the USFWS consider the benefits of designating critical habitat in Louisiana and Texas despite the current low number of nests because this designation requires agencies to ensure that their actions are “not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of [the loggerhead sea turtle] . . . or result in the destruction or adverse modification of habitat of [the loggerhead sea turtle].” If proactive measures are not taken to save the habitat of this species in Louisiana and Texas, the number of nests and turtles in these States may dwindle, causing further damage to this species.

Another commenter asked that Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay be included in the final rule as critical habitat because they are specific regions within the geographical area occupied by loggerhead sea turtles that are essential to conservation and require special management consideration.

Our Response: The USFWS agrees that nesting in the northern and western extent of the nesting range of the DPS is important to the conservation and recovery of the species. Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, and Delaware are not included in the designation based on the very low number of nests known to be laid in these States (less than 10 annually in each State from 2002 to 2011). However, protective measures are in place to protect the loggerhead sea turtle in these States because the species is listed under the Act. Federal agencies are already required to consult with the USFWS to ensure that they are not undertaking, funding, permitting, or authorizing actions likely to jeopardize the continued existence of loggerhead sea turtles.

Recommendations of Areas To Exclude From Critical Habitat Designation

(36) Comment: The Town of Holden Beach, North Carolina, contends that the specific areas proposed to be designated as critical habitat for the loggerhead sea turtle in North Carolina are arbitrary and capricious because (1) North Carolina's beaches' nesting density is low compared to South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, and (2) the USFWS did not provide any basis that North Carolina nesting beaches are required to provide genetic diversity. Other commenters contend that loggerhead sea turtle nesting density data do not support designation of critical habitat for any of North Carolina's beaches, and particularly not Bogue Banks, compared to South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Further, loggerhead sea turtle nesting in North Carolina represents a small fraction (approximately 1 percent) of not only the nesting by loggerhead sea turtles in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS, but also within the Northern Recovery Unit (approximately 13 percent) of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS.

Our Response: We understand that the beaches in North Carolina have lower nesting densities than in some of the other parts of the species' nesting range. However, for recovery of the DPS, it is important to conserve:

- Beaches that have the highest nesting densities, by State or region within a State;

- Beaches that have a good spatial distribution to ensure protection of genetic diversity;

- Beaches that collectively provide a good representation of total nesting; and

- Beaches adjacent to the high-density nesting beaches that can serve as expansion areas.

North Carolina falls within the Northern Recovery Unit. Within this Recovery Unit, we divided beach nesting densities into quartiles (four equal groups) by State and selected beaches that were within the upper quartile for designation as critical habitat. The reason we determined high nesting density beaches within each State (rather than the entire Northern Recovery Unit) was that it allowed for the inclusion of beaches near the northern extent of the range (North Carolina) that would otherwise be considered low density when compared with beaches in Georgia and South Carolina. This ensures good spatial distribution.

(37) Comment: The Town of Edisto Beach, South Carolina, requests to be excluded from the designation of critical habitat because the beach supports an average of only 80 nests a year and the typical sand on the beach is medium-sized and coarse and does not fit the USFWS's description of “deep, clean, relatively loose sand above high-tide level.”

Our Response: The beaches within the Town of Edisto Beach, South Carolina, meet the criteria for critical habitat described in the Criteria Used to Identify Critical Habitat section of the proposed and final rule, and specifically, the Northern Recovery Unit (i.e., unit supports expansion of nesting from an adjacent unit that has high-density nesting of loggerhead sea turtles in South Carolina, was occupied at the time of listing and is currently occupied, and contains all the physical or biological features and primary constituent elements). We note that “sand” in the proposed rule is defined as “. . . material predominately composed of carbonate, quartz, or similar material with a particle size distribution ranging between 0.062 mm and 4.76 mm (0.002 in and 0.187 in) (Wentworth and ASTM classification systems).” Medium and coarse sand meets this definition. We have no other information to support excluding the beaches within the Town of Edisto Beach under section 4(b)(2) of the Act.

(38) Comment: The Village of Bald Head Island, North Carolina, requests that the USFWS exclude Bald Head Island from critical habitat designation under section 4(b)(2) of the Act. The commenter explains that although not recognized in the proposed rule, Bald Head Island has a well-established and respected sea turtle protection program and as such believes the Island should be excluded, as similar consideration is being given to St. Johns, Volusia, and Indian River Counties, Florida, based on established habitat conservation plans. As one of NMFS's “index beaches,” Bald Head Island is nationally recognized for its sea turtle nesting activity, and for the Bald Head Island Conservancy's efforts to protect this resource. At this point, no additional benefit would be gained by the designation, and additional regulatory burdens may hinder local efforts.

Our Response: The beaches of Bald Head Island meet the criteria for critical habitat described in the Criteria Used to Identify Critical Habitat section of the proposed and final rule, and specifically, the Northern Recovery Unit (i.e., the unit has high-density nesting by loggerhead sea turtles in North Carolina, was occupied at the time of listing and is currently occupied, and contains all the physical or biological features and primary constituent elements). While Bald Head Island, like many of the beaches in this designation, has in place active sea turtle conservation efforts by Federal, State, local governments; private conservation organizations; and individuals, we have no knowledge of any plans that commit to dedicated funding of such efforts or that this program provides comprehensive sea turtle protection. Example programs could include beachfront lighting regulations, Start Printed Page 39766managed beach access, beach and dune habitat protection and restoration programs, or coastal development regulations. We recognize the efforts on Bald Head Island, but are not excluding the area, because the benefits of designating critical habitat outweigh the benefits of exclusion.

(39) Comment: The Escambia County Community and Environmental Department believes the areas jurisdictional to Escambia County on Perdido Key, Florida, within the Northern Gulf of Mexico Recovery Unit, should be considered for exclusion under section 4(b)(2) of the Act due to a pending programmatic HCP consistent with other communities such as St. Johns, Volusia, and Indian River Counties.

Our Response: The beaches of Escambia County meet the criteria for critical habitat. Although an area may be excluded if it is covered by an HCP, we must assess each HCP to determine whether the implementation of the conservation efforts benefits loggerhead sea turtles. Since this HCP has not yet been approved by the USFWS, or implemented in accordance with a permit, we are not excluding units within the proposed HCP coverage area.

Best Available Information and Methods

(40) Comment: The USFWS must include the most current nesting data through 2012.

Our Response: The Northwest Atlantic Ocean loggerhead sea turtle DPS was listed in 2011 (76 FR 58868). We have defined the terrestrial portion of the geographical area occupied for the loggerhead sea turtle as those U.S. areas in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS where nesting has been documented for the most part annually for the 10-year period from 2002 to 2011, as this time period represents the most consistent and standardized nest count surveys throughout the DPS' nesting range. Consistent with this definition, in the Northern Recovery Unit, Peninsular Florida Recovery Unit, and Northern Gulf of Mexico Recovery Unit (Florida and Alabama), we used loggerhead nests counts from 2006-2011 to calculate mean nest density for each beach and select the high density nesting beaches within each recovery unit. However, even though we did not rely on the 2012 nesting data in the proposed rule, we now find that they support the high density nesting beaches selected using the 2006-2011 mean nest density.

(41) Comment: The USFWS must incorporate any evidence about the impact of recent management changes, for example, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Special Regulation, which was implemented in 2012.

Our Response: While the USFWS may use information from management plans in discussing special management or protection considerations, we did not propose any critical habitat units within the Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CHNS). Therefore, discussion of the management changes at CHNS was not necessary because the changes do not affect any of the units in the designation.

(42) Comment: One commenter concurred with the identification of the physical and biological features of critical habitat, the primary constituent elements of critical habitat, and the listed threats. However, the commenter believes the information cited is stale and sometimes cited references have been misinterpreted or their incorporation is misleading.

Our Response: The USFWS updated the final rule with additional literature we received during the comment period and peer review. The USFWS collaborated with State technical advisors on the nesting data analysis. The peer review of the proposed rule did not indicate any of the references we used were misinterpreted or are misleading.

(43) Comment: It seems awkward that the USFWS did not seek peer review before submitting the proposed rule for public comment. It is acknowledged that as a result, the final rule may differ significantly from what is proposed. The commenter asks whether the public will get a second chance to comment on the next version of a rule, especially if there are significant changes.

Our Response: The USFWS conferred with scientific experts, including State technical advisors, during the development of the proposed rule and used the best scientific information available. Moreover, as discussed above, the peer review comments did not reflect suggestions for major changes to the rule. All revisions based on information we received during the public comment period are outlined in this final rule and do not represent any significant changes from the proposed rule.

(44) Comment: The discussion of the effects of coastal structures is narrow and biased. The quoting of Kaufman and Pilkey (1979) demonstrates a narrow understanding of the use of coastal structures. While there are outfalls within the State of Florida, they are outdated facilities designed prior to our modern understanding of coastal biology and engineering. The outfalls are few and their impacts are insignificant to the health of the large-scale sea turtle nesting habitat. The FDEP and FWC utilize existing regulatory programs where possible to reduce the impact of existing outfalls. New outfalls are prohibited by rule (62b-33, Florida Administrative Code).

Our Response: The USFWS verified that the information cited in Kaufman and Pilkey (1979) reflected our current understanding of coastal systems. There are existing outfalls along the loggerhead sea turtle nesting beach that create localized erosion channels, prevent natural dune establishment, and wash out sea turtle nests. The USFWS agrees that the design of new outfalls minimize the localized erosion; however, this impact continues for existing outfalls with the outdated design and is considered an impact to sea turtle nests.