-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 47254

AGENCY:

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Labor.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

OSHA is amending its occupational injury and illness recordkeeping regulation to require certain employers to electronically submit injury and illness information to OSHA that employers are already required to keep under the recordkeeping regulation. Specifically, OSHA is amending its regulation to require establishments with 100 or more employees in certain designated industries to electronically submit information from their OSHA Forms 300 and 301 to OSHA once a year. OSHA will not collect employee names or addresses, names of health care professionals, or names and addresses of facilities where treatment was provided if treatment was provided away from the worksite from the Forms 300 and 301. Establishments with 20 to 249 employees in certain industries will continue to be required to electronically submit information from their OSHA Form 300A annual summary to OSHA once a year. All establishments with 250 or more employees that are required to keep records under OSHA's injury and illness regulation will also continue to be required to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA on an annual basis. OSHA is also updating the NAICS codes used in appendix A, which designates the industries required to submit their Form 300A data, and is adding appendix B, which designates the industries required to submit Form 300 and Form 301 data. In addition, establishments will be required to include their company name when making electronic submissions to OSHA. OSHA intends to post some of the data from the annual electronic submissions on a public website after identifying and removing information that could reasonably be expected to identify individuals directly, such as individuals' names and contact information.

DATES:

This final rule becomes effective on January 1, 2024.

Collections of information: There are collections of information contained in this final rule (see Section V, OMB Review Under the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995). Notwithstanding the general date of applicability for the requirements contained in the final rule, affected parties do not have to comply with the collections of information until the Department of Labor publishes a separate document in the Federal Register announcing that the Office of Management and Budget has approved them under the Paperwork Reduction Act.

ADDRESSES:

Electronic copies of this Federal Register document and news releases are available at OSHA's website at https://www.osha.gov.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

For press inquiries: Frank Meilinger, Director, Office of Communications, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, U.S. Department of Labor; telephone (202) 693–1999; email: meilinger.francis2@dol.gov.

For general information and technical inquiries: Lee Anne Jillings, Director, Directorate of Technical Support and Emergency Management, U.S. Department of Labor; telephone (202) 693–2300; email: Jillings.LeeAnne@dol.gov.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Background

A. References and Exhibits

B. Introduction

C. Regulatory History

D. Related Litigation

E. Injury and Illness Data Collection

II. Legal Authority

A. Statutory Authority To Promulgate the Rule

B. Fourth Amendment Issues

C. Publication of Collected Data and FOIA

D. Reasoned Explanation for Policy Change

III. Summary and Explanation of the Final Rule

A. Section 1904.41(a)(1)(i) and (ii)—Annual Electronic Submission of Information From OSHA Form 300A Summary of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses

1. Section 1904.41(a)(1)(i)—Establishments With 20–249 employees That Are Required To Submit Information From OSHA Form 300A

2. Section 1904.41(a)(1)(ii)—Establishments With 250 or More Employees That Are Required To Submit Information From OSHA Form 300A

3. Restructuring of Previous Section 1904.41(a)(1) and (2) Into Final Section 1904.41(a)(1)(i) and (ii)

4. Updating Appendix A

B. Section 1904.41(a)(2)—Annual Electronic Submission of OSHA Form 300 Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses and OSHA Form 301 Injury and Illness Incident Report by Establishments With 100 or More Employees in Designated Industries)

1. Covered Establishments and Industries

a. The Size Threshold for Submitting Information From OSHA Forms 300 and 301

b. The Criteria for Determining the Industries in Appendix B to Subpart E

c. Cut-Off Rates for Determining the Industries in Appendix B to Subpart E

d. Using the Most Current Data To Determine Designated Industries

e. Industries Included in Final Appendix B After Applying the Final Criteria, Cut-Off Rates, and Data Sources

2. Information To Be Submitted

3. Publication of Electronic Data

4. Benefits of Collecting and Publishing Data From Forms 300 and 301

a. General Benefits of Collecting and Publishing Data From Forms 300 and 301

b. Beneficial Ways That OSHA Can Use The Data From Forms 300 and 301

c. Beneficial Ways That Employers Can Use the Data From Forms 300 and 301

d. Beneficial Ways That Employees Can Use the Data From Forms 300 and 301

e. Beneficial Ways That Federal and State Agencies Can Use the Data From Forms 300 and 301

f. Beneficial Ways That Researchers Can Use the Data From Forms 300 and 301

g. Beneficial Ways That Workplace Safety Consultants Can Use the Data From Forms 300 and 301

h. Beneficial Ways That Members of the Public and Other Interested Parties Can Use the Data From Forms 300 and 301

5. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

6. Safeguarding Individual Privacy (Direct Identification)

7. Indirect Identification of Individuals

8. The Experience of Other Federal Agencies

9. Risk of Cyber Attack

10. The Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

11. The Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA)

12. The Privacy Act

13. Privacy Impact Assessment

14. Other Issues Related to OSHA's Proposal To Require the Submission of and Then Publish Certain Data From Establishments' Forms 300 and 301

a. Miscellaneous Comments

b. The Effect of the Rule on the Accuracy of Injury and Illness Records

c. Collecting and Processing the Data From Forms 300 and 301 Will Help OSHA Use Its Resources More Effectively

d. OSHA's Capacity To Collect and Process the Data From Forms 300 and 301

e. Data Submission

f. Tools To Make the Collected Data From Forms 300 and 301 More Useful

C. Section 1904.41(b)(1)

D. Section 1904.41(b)(9)

1. Collecting Employee Names

2. Excluding Other Specified Fields

E. Section 1904.41(b)(10)

F. Section 1904.41(c)

G. Additional Comments Which Concern More Than One Section of the Proposal Start Printed Page 47255

1. General Comments

2. Misunderstandings About Scope

3. Diversion of Resources

4. Lagging v. Leading Indicators

5. Employer Shaming

6. Impact on Employee Recruiting

7. Legal Disputes

8. No Fault Recordkeeping

9. Confidentiality of Business Locations

10. Employer-Vaccine-Mandate-Related Concerns

11. Constitutional Issues and OSHA's Authority To Publish Information From Forms 300 and 301

a. The First Amendment

b. The Fourth Amendment

c. The Fifth Amendment

d. OSHA's Authority To Publish Information Submitted Under This Rule

12. Administrative Issues

a. Public Hearing

b. The Advisory Committee on Construction Safety and Health (ACCSH)

c. Reasonable Alternatives Considered

IV. Final Economic Analysis and Regulatory Flexibility Certification

A. Introduction

B. Changes From the Preliminary Economic Analysis (PEA) (Reflecting Changes in the Final Rule From the Proposal)

1. Continued Submission of OSHA 300A Annual Summaries by Establishments With 250 or More Employees

2. Additional Appendix B Industries

3. Updated Data

C. Cost

1. Wages

a. Wage Estimates in the PEA

b. Comments on OSHA's Wage Estimates

c. Wage Estimates in the FEA

2. Estimated Case Counts

3. Familiarization

4. Record Submission

5. Custom Forms

6. Batch-File Submissions

7. Software/System Upgrades Needed

8. Other Costs

a. Harm to Reputation

b. Additional Time Needed To Review for PII

c. Company Name

d. Training Costs

D. Effect on Prices

E. Budget Costs to the Government

F. Total Cost

G. Benefits

H. Economic Feasibility

I. Regulatory Flexibility Certification

V. OMB Review Under the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995

A. Overview

B. Summary of Information Collection Requirements

VI. Unfunded Mandates

VII. Federalism

VIII. State Plans

IX. National Environmental Policy Act

X. Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments Authority and Signature

I. Background

A. References and Exhibits

In this preamble, OSHA references documents in Docket No. OSHA–2021–0006, the docket for this rulemaking. The docket is available at http://www.regulations.gov, the Federal eRulemaking Portal.

When citing exhibits in the docket, OSHA includes the term “Document ID” followed by the last four digits of the Document ID number. For example, OSHA's preliminary economic analysis is in the docket as OSHA–2021–0006–0002. Citations also include the attachment number or other attachment identifier, if applicable, page numbers (designated “p.” or “Tr.” for pages from a hearing transcript), and in a limited number of cases a footnote number (designated “Fn.”). In a citation that contains two or more Document ID numbers, the Document ID numbers are separated by semi-colons ( e.g., “Document ID 1231, Attachment 1, p. 6; 1383, Attachment 1, p. 2”).

All materials in the docket, including public comments, supporting materials, meeting transcripts, and other documents, are listed on http://www.regulations.gov. However, some exhibits ( e.g., copyrighted material) are not available to read or download from that web page. All materials in the docket, including copyrighted material, are available for inspection through the OSHA Docket Office. Contact the OSHA Docket Office at (202) 693–2350 (TTY (877) 889–5627) for assistance in locating docket submissions.

B. Introduction

OSHA's regulation at 29 CFR part 1904 requires employers with more than 10 employees in most industries to keep records of occupational injuries and illnesses at their establishments. Employers covered by the regulation must use three forms, or their equivalent, to record recordable employee injuries and illnesses:

• OSHA Form 300, the Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses. This form includes information about the employee's name, job title, date of the injury or illness, where the injury or illness occurred, description of the injury or illness ( e.g., body part affected), and the outcome of the injury or illness ( e.g., death, days away from work, job transfer or restriction).

- OSHA Form 301, the Injury and Illness Incident Report. This form includes the employee's name and address, date of birth, date hired, and gender and the name and address of the health care professional that treated the employee, as well as more detailed information about where and how the injury or illness occurred.

- OSHA Form 300A, the Annual Summary of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses. This form includes general information about an employer's workplace, such as the average number of employees and total number of hours worked by all employees during the calendar year. It does not contain information about individual employees. Employers are required to prepare this form at the end of each year and post the form in a visible location in the workplace from February 1 to April 30 of the year following the year covered by the form.

Section 1904.41 of the previous recordkeeping regulation also required two groups of establishments to electronically submit injury and illness data to OSHA once a year.

- § 1904.41(a)(1) required establishments with 250 or more employees in industries that are required to routinely keep OSHA injury and illness records to electronically submit information from the Form 300A summary to OSHA once a year.

- § 1904.41(a)(2) required establishments with 20–249 employees in certain designated industries (those listed on appendix A of part 1904 subpart E) to electronically submit information from their Form 300A summary to OSHA once a year.

Also, § 1904.41(a)(4) required each establishment that must electronically submit injury and illness information to OSHA to provide their Employer Identification Number (EIN) in their submittal.

Under this final rule, three groups of establishments will be required to electronically submit information from their injury and illness recordkeeping forms to OSHA once a year.

- Establishments with 20–249 employees in certain designated industries (listed in appendix A to subpart E) will continue to be required to electronically submit information from their Form 300A annual summary to OSHA once a year (final § 1904.41(a)(1)(i)). OSHA is also updating the NAICS codes used for appendix A to subpart E.

- Establishments with 250 or more employees in industries that are required to routinely keep OSHA injury and illness records will continue to be required to electronically submit information from the Form 300A to OSHA once a year (final § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii)).

• Establishments with 100 or more employees in certain designated industries (listed in new appendix B to subpart E) will be newly required to electronically submit information from their OSHA Forms 300 and 301 to OSHA once a year (final § 1904.41(a)(2)). The industries listed in new appendix B were chosen based on Start Printed Page 47256 three measures of industry hazardousness.

OSHA will also require establishments to include their company name when making electronic submissions to OSHA (final § 1904.41(b)(10)).

Additionally, although publication is not part of the regulatory requirements of this final rule, OSHA intends to post the collected establishment-specific, case-specific injury and illness information online. As discussed in more detail below, the agency will seek to minimize the possibility of the release of information that could reasonably be expected to identify individuals directly, such as employee name, contact information, and name of physician or health care professional. OSHA will minimize the possibility of releasing such information in multiple ways, including by limiting the worker information collected, designing the collection system to provide extra protections for some of the information that employers will be required to submit, withholding certain fields from public disclosure, and using automated software to identify and remove information that could reasonably be expected to identify individuals directly.

OSHA has determined that the data collection will assist the agency in its statutory mission to assure safe and healthful working conditions for working people (see 29 U.S.C. 651(b)). In addition, OSHA has determined that the expanded public access to establishment-specific, case-specific injury and illness data will allow employers, employees, potential employees, employee representatives, customers, potential customers, researchers, and the general public to make more informed decisions about workplace safety and health at a given establishment. OSHA believes that this accessibility will ultimately result in the reduction of occupational injuries and illnesses.

OSHA estimates that this rule will have economic costs of $7.7 million per year, including $7.1 million per year to the private sector, with average costs of $136 per year for affected establishments with 100 or more employees, annualized over 10 years with a discount rate of seven percent. The agency believes that the annual benefits, while unquantified, significantly exceed the annual costs.

C. Regulatory History

As discussed in section II, Legal Authority, the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act or Act) requires employers to keep records of employee illnesses and injuries as prescribed by OSHA through regulation. OSHA's regulations on recording and reporting occupational injuries and illnesses (29 CFR part 1904) were first issued in 1971 (36 FR 12612 (July 2, 1971)). These regulations require the recording of work-related injuries and illnesses that involve death, loss of consciousness, days away from work, restricted work or transfer to another job, medical treatment beyond first aid, or diagnosis of a significant injury or illness by a physician or other licensed health care professional (29 CFR 1904.7).

On July 29, 1977, OSHA amended these regulations to partially exempt businesses having ten or fewer employees during the previous calendar year from the requirement to record occupational injuries and illnesses (42 FR 38568). Then, on December 28, 1982, OSHA amended the regulations again to partially exempt establishments in certain lower-hazard industries from the requirement to record occupational injuries and illnesses (47 FR 57699).[1] OSHA also amended the recordkeeping regulations in 1994 (Reporting of Fatality or Multiple Hospitalization Incidents, 59 FR 15594) and 1997 (Reporting Occupational Injury and Illness Data to OSHA, 62 FR 6434). Under the version of § 1904.41 added by the 1997 final rule, OSHA began requiring certain employers to submit their 300A data to OSHA annually through the OSHA Data Initiative (ODI). Through the ODI, OSHA collected data on injuries and acute illnesses attributable to work-related activities in the private sector from approximately 80,000 establishments in selected high-hazard industries. The agency used these data to calculate establishment-specific injury and illness rates, and, in combination with other data sources, to target enforcement and compliance assistance activities.

On January 19, 2001, OSHA issued a final rule amending its requirements for the recording and reporting of occupational injuries and illnesses (29 CFR parts 1904 and 1952), along with the forms employers use to record those injuries and illnesses (66 FR 5916). The final rule also updated the list of industries that are partially exempt from recording occupational injuries and illnesses.

On September 18, 2014, OSHA again amended the regulations to require employers to report work-related fatalities and severe injuries—in-patient hospitalizations, amputations, and losses of an eye—to OSHA and to allow electronic reporting of these events (79 FR 56130). The final rule also revised the list of industries that are partially exempt from recording occupational injuries and illnesses.

On May 12, 2016, OSHA amended the regulations on recording and reporting occupational injuries and illnesses to require employers, on an annual basis, to submit electronically to OSHA injury and illness information that employers are already required to keep under part 1904 (81 FR 29624). Under the 2016 revisions, establishments with 250 or more employees that are routinely required to keep records were required to electronically submit information from their OSHA Forms 300, 300A, and 301 to OSHA or OSHA's designee once a year, and establishments with 20 to 249 employees in certain designated industries were required to electronically submit information from their OSHA annual summary (Form 300A) to OSHA or OSHA's designee once a year. In addition, that final rule required employers, upon notification, to electronically submit information from part 1904 recordkeeping forms to OSHA or OSHA's designee. These provisions became effective on January 1, 2017, with an initial submission deadline of July 1, 2017, for 2016 Form 300A data. That submission deadline was subsequently extended to December 15, 2017 (82 FR 55761). The initial submission deadline for electronic submission of information from OSHA Forms 300 and 301 was July 1, 2018. Because of a subsequent rulemaking, OSHA never received the data submissions from Forms 300 and 301 that the 2016 final rule anticipated.

On January 25, 2019, OSHA issued a final rule that amended the recordkeeping regulations to remove the requirement for establishments with 250 or more employees that are routinely required to keep records to electronically submit information from their OSHA Forms 300 and 301 to OSHA or OSHA's designee once a year. As a result, those establishments were required to electronically submit only information from their OSHA 300A Start Printed Page 47257 annual summary. The 2019 final rule also added a requirement for covered employers to submit their Employer Identification Number (EIN) electronically along with their injury and illness data submission (83 FR 36494, 84 FR 380, 395–97).

On March 30, 2022, OSHA issued a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM or proposed rule) proposing to amend the recordkeeping regulations to require establishments with 100 or more employees in certain designated industries to electronically submit information from their OSHA Forms 300 and 301 to OSHA once a year (87 FR 18528). In addition, OSHA proposed to continue the requirement for establishments with 20 or more employees in certain designated industries to electronically submit data from their OSHA Form 300A annual summary to OSHA once a year. OSHA also proposed to update the appendices containing the designated industries covered by the electronic submission requirement and to remove the requirement for establishments with 250 or more employees not in a designated industry to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA on an annual basis. Further, OSHA expressed its intention to post the data from the proposed electronic submission requirement on a public website after identifying and removing information that could reasonably be expected to identify individuals directly, such as individuals' names and contact information. Finally, OSHA proposed to require establishments to include their company name when making electronic submissions to OSHA.

Comments on the NPRM were initially due on May 30, 2022 (87 FR18528). However, in response to requests for an extension, OSHA published a second Federal Register notice on May 25, 2022, extending the comment period until June 30, 2022 (87 FR 31793). By the end of the extended comment period, OSHA had received 87 comments on the proposed rule. The issues raised in those comments are addressed herein.

D. Related Litigation

Both the 2016 and 2019 OSHA final rules that addressed the electronic submission of injury and illness data were challenged in court. In Texo ABC/AGC, Inc., et al. v. Acosta, No. 3:16–cv–01998–L (N.D. Tex. filed July 8, 2016), and NAHB, et al. v. Acosta, No. 5:17–cv–00009–PRW (W.D. Okla. filed Jan. 4, 2017), industry groups challenged OSHA's 2016 final rule that required establishments with 250 or more employees to electronically submit data from their OSHA Forms 300 and 301 to OSHA (as well as other requirements not relevant to this rulemaking). The complaints alleged that the publication of establishment-specific injury and illness data would lead to misuse of confidential and proprietary information by the public and special interest groups. The complaints also alleged that publication of the data exceeds OSHA's authority under the OSH Act and is unconstitutional under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. After OSHA published a notice in the Federal Register on June 28, 2017, noting that the agency planned to publish a proposal that would reconsider the requirements of the 2016 final rule (82 FR 29261), Texo was administratively closed. The plaintiffs in NAHB dropped their claims relating to the 300 and 301 data submission requirement after the 2019 final rule was published (and moved forward with their other claims, which are still pending in the Western District of Oklahoma).

In Public Citizen Health Research Group et al. v. Pizzella, No. 1:19–cv–00166 (D.D.C. filed Jan. 25, 2019) and State of New Jersey et al. v. Pizzella, No. 1:19–cv–00621 (D.D.C. filed Mar. 6, 2019), a group of public health organizations and a group of States filed separate lawsuits challenging OSHA's 2019 final rule rescinding the requirement for certain employers to submit the data from OSHA Forms 300 and 301 to OSHA electronically each year. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia resolved the two cases in a consolidated opinion and held that rescinding the provision was within the agency's discretion ( Public Citizen Health Research Group et al. v. Pizzella, No. 1:19–cv–00166–TJK (D.D.C. Jan. 11, 2021)). The court first dismissed Public Citizen's complaint for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction. Next, turning to the merits of the States' complaint, the court held that OSHA's rescission of the Form 300 and Form 301 data-submission requirements was within the agency's discretion based on its rebalancing of the “uncertain benefits” of collecting the 300 and 301 data against the diversion of OSHA's resources from other efforts and potential privacy harms to employees. The court also rejected the plaintiffs' assertion that OSHA's reasons for the 2019 final rule were internally inconsistent. Both groups of plaintiffs have appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (Nos. 21–5016, 21–5018).

Additionally, since 2020, the Department of Labor (DOL) has received multiple adverse decisions regarding the release of electronically submitted 300A data under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). In each of the cases, OSHA argued that electronically submitted 300A injury and illness data are exempt from disclosure pursuant to the confidentiality exemption in FOIA Exemption 4. Two courts, one in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California and another in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, disagreed with OSHA's position (see Center for Investigative Reporting, et al., v. Department of Labor, No. 4:18–cv–02414–DMR, 2020 WL 2995209 (N.D. Cal. June 4, 2020); Public Citizen Foundation v. United States Department of Labor, et al., No. 1:18–cv–00117 (D.D.C. June 23, 2020)). In addition, on July 6, 2020, the Department received an adverse ruling from a magistrate judge in the Northern District of California in a FOIA case involving Amazon fulfillment centers. In that case, plaintiffs sought the release of individual 300A forms, which consisted of summaries of Amazon's work-related injuries and illnesses and which were provided to OSHA compliance officers during specific OSHA inspections of Amazon fulfillment centers in Ohio and Illinois (see Center for Investigative Reporting, et al., v. Department of Labor, No. 3:19–cv–05603–SK, 2020 WL 3639646 (N.D. Cal. July 6, 2020)).

In holding that FOIA Exemption 4 was inapplicable, the courts rejected OSHA's position that electronically submitted 300A injury and illness data are covered under the confidentiality exemption in FOIA Exemption 4. The decisions noted that the 300A form is posted in the workplace for three months and that there is no expectation that the employer must keep these data confidential or private. As a result, OSHA provided the requested 300A data to the plaintiffs, and posted collected 300A data on its public website beginning in August 2020. The data are available at https://www.osha.gov/Establishment-Specific-Injury-and-Illness-Data and include the submissions for calendar years 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021.

E. Injury and Illness Data Collection

Currently, two U.S. Department of Labor data collections request and compile information from the OSHA injury and illness records that certain employers are required to keep under 29 CFR part 1904: the annual collection conducted by OSHA under 29 CFR 1904.41 (Electronic Submission of Employer Identification Number (EIN) and Injury and Illness Records to Start Printed Page 47258 OSHA), and the annual Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) under 29 CFR 1904.42. This final rule amends the regulation at § 1904.41. It does not change the SOII or the authority for the SOII set forth in § 1904.42.

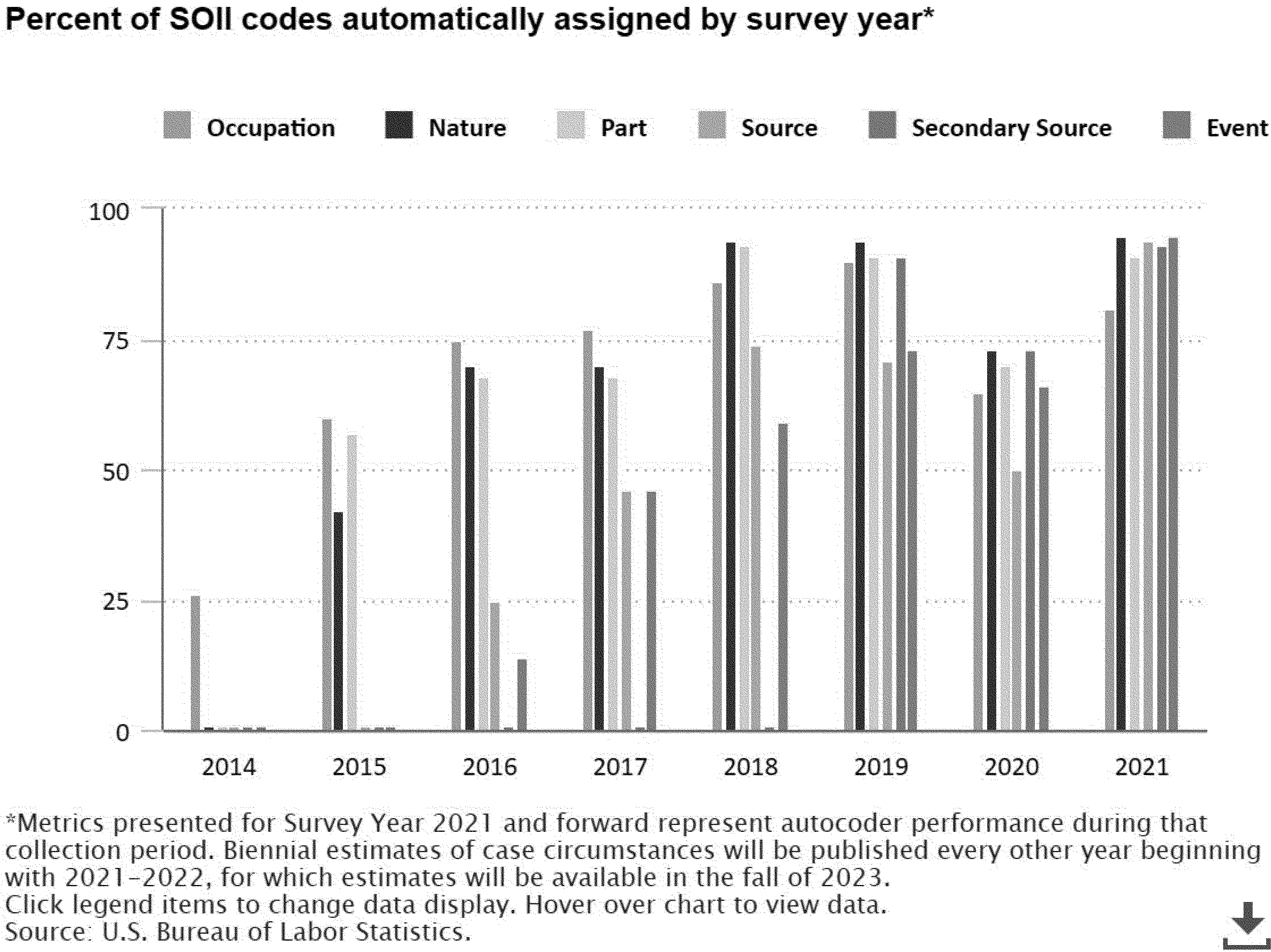

The BLS SOII is an establishment-based survey used to estimate nationally representative incidence rates and counts of workplace injuries and illnesses. It also provides detailed case and demographic data for cases that involve one or more days away from work (DAFW) and for days of job transfer and restriction (DJTR). Each year, BLS collects data from Forms 300, 301, and 300A from a scientifically selected probability sample of about 230,000 establishments, covering nearly all private-sector industries, as well as State and local government. Title 44 U.S.C. 3572 prohibits BLS from releasing establishment-specific and case-specific data to the general public or to OSHA. However, BLS has modified its collection procedures to be able to automatically import certain Form 300A submissions from the OSHA ITA into the BLS SOII Internet Data Collection Facility (IDCF). As discussed below, the Department is continuing to evaluate opportunities to further reduce duplicative reporting.

II. Legal Authority

A. Statutory Authority To Promulgate the Rule

OSHA is issuing this final rule pursuant to authority expressly granted by several provisions of the OSH Act that address the recording and reporting of occupational injuries and illnesses. Section 2(b)(12) of the OSH Act states that one of the purposes of the OSH Act is to “assure so far as possible . . . safe and healthful working conditions . . . by providing for appropriate reporting procedures . . . which . . . will help achieve the objectives of th[e] Act and accurately describe the nature of the occupational safety and health problem” (29 U.S.C. 651(b)(12)). Section 8(c)(1) requires each employer to “make, keep and preserve, and make available to the Secretary [of Labor] . . . , such records regarding his activities relating to this Act as the Secretary . . . may prescribe by regulation as necessary or appropriate for the enforcement of this Act or for developing information regarding the causes and prevention of occupational accidents and illnesses” (29 U.S.C. 657(c)(1)). Section 8(c)(2) directs the Secretary to prescribe regulations “requiring employers to maintain accurate records of, and to make periodic reports on, work-related deaths, injuries and illnesses other than minor injuries requiring only first aid treatment and which do not involve medical treatment, loss of consciousness, restriction of work or motion, or transfer to another job” (29 U.S.C. 657(c)(2)).

Section 8(g)(1) authorizes the Secretary “to compile, analyze, and publish, whether in summary or detailed form, all reports or information obtained under this section” (29 U.S.C. 657(g)(1)). Section 8(g)(2) of the Act broadly empowers the Secretary to “prescribe such rules and regulations as he may deem necessary to carry out [his] responsibilities under th[e] Act” (29 U.S.C. 657(g)(2)).

Section 24 of the OSH Act (29 U.S.C. 673) contains a similar grant of authority. This section requires the Secretary to “develop and maintain an effective program of collection, compilation, and analysis of occupational safety and health statistics” and “compile accurate statistics on work injuries and illnesses which shall include all disabling, serious, or significant injuries and illnesses . . .” (29 U.S.C. 673(a)). Section 24 also requires employers to “file such reports with the Secretary as he shall prescribe by regulation” (29 U.S.C. 673(e)). These reports are to be based on “the records made and kept pursuant to section 8(c) of this Act” (29 U.S.C. 673(e)).

Section 20 of the Act (29 U.S.C. 669) contains additional implicit authority for collecting and disseminating data on occupational injuries and illnesses. Section 20(a) empowers the Secretaries of Labor and Health and Human Services to consult on research concerning occupational safety and health problems, and provides for the use of such research, “and other information available,” in developing criteria on toxic materials and harmful physical agents. Section 20(d) states that “[i]nformation obtained by the Secretary . . . under this section shall be disseminated by the Secretary to employers and employees and organizations thereof” (29 U.S.C. 669(d)).

The OSH Act authorizes the Secretary of Labor to issue two types of occupational safety and health rules: standards and regulations. Standards, which are authorized by Section 6 of the Act (29 U.S.C. 655), aim to correct particular identified workplace hazards, while regulations further the general enforcement and detection purposes of the OSH Act (see Workplace Health & Safety Council v. Reich, 56 F.3d 1465, 1468 (D.C. Cir. 1995) (citing La. Chem. Ass'n v. Bingham, 657 F.2d 777, 781–82 (5th Cir. 1981)); United Steelworkers of Am. v. Auchter, 763 F.2d 728, 735 (3d Cir. 1985)). Recordkeeping requirements promulgated under the Act are characterized as regulations (see 29 U.S.C. 657 (using the term “regulations” to describe recordkeeping requirements); see also Workplace Health & Safety Council v. Reich, 56 F.3d 1465, 1468 (D.C. Cir. 1995) (citing La. Chem. Ass'n. v. Bingham, 657 F.2d 777, 781–82 (5th Cir. 1981); United Steelworkers of Am. v. Auchter, 763 F.2d 728, 735 (3d Cir. 1985)).

B. Fourth Amendment Issues

This final rule does not infringe on employers' Fourth Amendment rights. The Fourth Amendment protects against searches and seizures of private property by the government, but only when a person has a “legitimate expectation of privacy” in the object of the search or seizure ( Rakas v. Illinois, 439 U.S. 128, 143–47 (1978)). There is little or no expectation of privacy in records that are required by the government to be kept and made available ( Free Speech Coalition v. Holder, 729 F. Supp. 2d 691, 747, 750–51 (E.D. Pa. 2010) (citing cases); United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435, 442–43 (1976); cf. Shapiro v. United States, 335 U.S. 1, 33 (1948) (no Fifth Amendment interest in required records)). Accordingly, the Fourth Circuit held, in McLaughlin v. A.B. Chance, that an employer has little expectation of privacy in the records of occupational injuries and illnesses kept pursuant to OSHA regulations and must disclose them to the agency on request (842 F.2d 724, 727–28 (4th Cir. 1988)).

Even if there were an expectation of privacy, the Fourth Amendment prohibits only unreasonable intrusions by the government ( Kentucky v. King, 131 S. Ct. 1849, 1856 (2011)). The information submission requirements in this final rule are reasonable. The requirements serve a substantial government interest in the health and safety of workers, have a strong statutory basis, and rest on reasonable, objective criteria for determining which employers must report information to OSHA (see New York v. Burger, 482 U.S. 691, 702–703 (1987)).

OSHA notes that two courts have held, contrary to A.B. Chance, that the Fourth Amendment requires prior judicial review of the reasonableness of an OSHA field inspector's demand for access to injury and illness logs before the agency could issue a citation for denial of access ( McLaughlin v. Kings Island, 849 F.2d 990 (6th Cir. 1988); Brock v. Emerson Electric Co., 834 F.2d Start Printed Page 47259 994 (11th Cir. 1987)). Those decisions are inapposite here. The courts based their rulings on a concern that field enforcement staff had unbridled discretion to choose the employers they would inspect and the circumstances in which they would demand access to employer records. The Emerson Electric court specifically noted that in situations where “businesses or individuals are required to report particular information to the government on a regular basis[,] a uniform statutory or regulatory reporting requirement [would] satisf[y] the Fourth Amendment concern regarding the potential for arbitrary invasions of privacy” (834 F.2d at 997, n.2). This rule, like that hypothetical, establishes general reporting requirements based on objective criteria and does not vest field staff with any discretion. The employers that are required to report data, the information they must report, and the time when they must report it are clearly identified in the text of the rule and in supplemental notices that will be published pursuant to the Paperwork Reduction Act.

C. Publication of Collected Data and FOIA

FOIA generally supports OSHA's intention to publish information on a publicly available website. FOIA provides that certain Federal agency records must be routinely made “available for public inspection in an electronic format” (see 5 U.S.C. 552(a)(2) (2016)). Subsection (a)(2)(D)(ii) provides that agencies must include any records processed and disclosed in response to a FOIA request that “the agency determines have become or are likely to become the subject of subsequent requests for substantially the same records” or “have been requested 3 or more times.”

Based on its experience, OSHA believes that the recordkeeping information from the Forms 300, 301, and 300A required to be submitted under this rule will likely be the subject of multiple FOIA requests in the future. Consequently, the agency plans to place the recordkeeping information that will be posted on the public OSHA website in its Electronic FOIA Library. Since agencies may “withhold” ( i.e., not make available) a record (or portion of such a record) if it falls within a FOIA exemption, just as they can do in response to FOIA requests, OSHA will place the published information in its FOIA Library consistent with all FOIA exemptions.

D. Reasoned Explanation for Policy Change

When a Federal agency action changes or reverses prior policy, that action is subject to the same standard of review as an action that addresses an issue for the first time or is consistent with prior policy ( F.C.C. v. Fox Television Stations, Inc., 556 U.S. 502, 514–15 (2009)). As with any other agency action, agencies must simply “provide a reasoned explanation for the change” ( Encino Motorcars, LLC v. Navarro, 579 U.S. 211, 221 (2016)). An agency that is changing policy must “display awareness that it is changing position,” but “need not demonstrate . . . that the reasons for the new policy are better than the reasons for the old one”; “it suffices that the new policy is permissible under the statute, that there are good reasons for it, and that the agency believes it to be better, which the conscious change of course adequately indicates” ( F.C.C., 556 U.S. at 515; accord DHS v. Regents of Univ. of California, 140 S. Ct. 1891 (2020); Encino Motorcars, LLC, 579 at 221; see also Advocates for Highway & Auto Safety v. FMCSA, 41 F.4th 586 (D.C. Cir. 2022) (upholding 2020 change to 2015 rule); Overdevest Nurseries, L.P. v. Walsh, 2 F. 4th 977 (D.C. Cir. 2021) (upholding 2010 change to 2008 rule)). In sum, the Administrative Procedure Act imposes “no special burden when an agency elects to change course” ( Home Care Ass'n of Am. v. Weil, 799 F.3d 1084, 1095 (D.C. Cir. 2015)).

Although agencies may need to provide more detailed explanations for changes in policy that “engendered serious reliance interests,” F.C.C. v. Fox Television Stations, Inc., 556 U.S. 502, 515 (2009), OSHA has found no such reliance interests at stake in this rulemaking. The prior policy, contained within the 2019 final recordkeeping rule, represented a return to the pre-2016 status quo wherein large employers were not required to submit their Form 300 and Form 301 information to OSHA. Essentially, the prior policy relieved employers of the requirement to incur the costs they would have had to incur to comply with the 2016 final rule. Therefore, the prior policy did not require employers to take any steps or invest any resources to comply with it. Further, OSHA made it clear in the 2019 final rule that its decision was based on a temporal weighing of the potential risks to privacy against the benefits of collecting the data ( e.g., “OSHA has determined that because it already has systems in place to use the 300A data for enforcement targeting and compliance assistance without impacting worker privacy, and because the Form 300 and 301 data would provide uncertain additional value, the Form 300A data are sufficient for enforcement targeting and compliance assistance at this time ” (84 FR 392)). Employers were therefore placed on notice that the policy announced in the 2019 rule could change based on OSHA's weighing of the relevant considerations over time, further alleviating any reliance interests the rule might have engendered. In any event, OSHA provides detailed and specific reasons for the change in prior policy throughout this preamble.[2]

III. Summary and Explanation of the Final Rule

OSHA is amending its occupational injury and illness recordkeeping regulations at 29 CFR part 1904 to require certain employers to electronically submit injury and illness information to OSHA that employers are already required to keep. Specifically, this final rule requires establishments with 100 or more employees in certain designated industries ( i.e., the industries on appendix B to subpart E of part 1904) to electronically submit information from their OSHA Forms 300 and 301 to OSHA once a year. OSHA will not collect certain information, like employee and healthcare provider names and addresses, from the Forms 300 and 301 in order to protect the privacy of workers and other individuals identified on those forms. In addition, the final rule retains the requirements for the annual electronic submission of information from the Form 300A annual summary. Establishments with 20 to 249 employees in certain industries ( i.e., those on appendix A to subpart E of part 1904) will continue to be required to electronically submit information from their OSHA Form 300A to OSHA once a year. And, all establishments with 250 or more employees that are required to keep records under part 1904 will continue to be required to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA once a year. In addition, the final rule requires establishments to Start Printed Page 47260 include their legal company name as part of their annual submission. OSHA intends to post some of the information from these annual electronic submissions on a public website after removing any submitted information that could reasonably be expected to identify individuals directly. OSHA received a number of comments on the proposed rule, which was published in March 2022.

Many commenters strongly support this rulemaking effort ( e.g., Docket IDs 0008, 0026, 0029, 0033, 0040, 0047, 0048, 0049, 0061, 0063, 0067, 0069, 0073, 0084, 0089), while others are strenuously opposed ( e.g., Docket IDs 0043, 0050, 0052, 0053, 0058, 0059, 0062, 0088, 0090). Several commenters requested that OSHA withdraw the proposed rule ( e.g., Docket IDs 0042, 0065, 0075). Organizations that represent employees generally advocated for OSHA to proceed with the rulemaking, arguing that collecting and publishing workplace illness and injury information will lead to improvements in worker safety and health in a number of different ways. Organizations commenting on behalf of employers argued, in many cases, that the required submission and subsequent publication of this information could harm businesses or result in violations of employees' privacy. OSHA has evaluated the public comments and other evidence in the record and agrees with commenters who believe that electronic submission of worker injury and illness information to OSHA will lead to safer workplaces. The agency has decided to move forward with a final rule requiring electronic submission of this information.

Public comments regarding the final regulatory provisions and specific issues related to the submission and publication of workplace injury and illness information are discussed throughout this preamble. The Summary and Explanation is organized by regulatory provision, with issues related to each provision discussed in the section for that provision. Comments not specifically related to a regulatory provision and comments that apply to the rulemaking in general are addressed at the end of the Summary and Explanation. OSHA's economic analysis and related issues and comments are discussed in Section IV, Final Economic Analysis, following the Summary and Explanation.

A. Section 1904.41(a)(1)(i) and (ii)—Annual Electronic Submission of Information From OSHA Form 300A Summary of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses

The final rule requires electronic submission of Form 300A information from two categories of establishments. First, § 1904.41(a)(1)(i) requires establishments with 20–249 employees that are in an industry listed in appendix A of subpart E of part 1904 to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA. The industries included on appendix A are listed by the NAICS codes from 2017. Second, § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii) requires establishments with 250 or more employees that are required to keep records under part 1904 to electronically submit their Form 300A information to OSHA. For all establishments, the size of the establishment is determined based on how many employees the establishment had during the previous calendar year. Data must be submitted annually, for the previous calendar year, by the date specified in § 1904.41(c), which is March 2.

As discussed in more detail below, the requirements for establishment submission of Form 300A information under the final rule are substantively identical to the requirements previously found in § 1904.41(a)(1) and (a)(2). In other words, all establishments with 250 or more employees are still required to submit information from Form 300A, and establishments with 20–249 employees in industries on appendix A of subpart E are still required to submit information from their Form 300A. However, OSHA has made minor revisions to the language of final § 1904.41(a)(1)(i) and (ii), and the final regulatory text of both provisions has been restructured, with final § 1904.41(a)(1)(i) addressing the Form 300A submission requirements for establishments with 20–249 employees and final § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii) addressing the Form 300A submission requirements for establishments with 250 or more employees. As discussed elsewhere in this preamble, final § 1904.41(a)(2) addresses the submission requirements for OSHA Forms 300 and 301 by establishments with 100 or more employees in the industries listed in appendix B. The final rule's requirements in § 1904.41(a)(1) are discussed below, along with the proposed provisions and related evidence in the rulemaking record.

1. Section 1904.41(a)(1)(i)—Establishments With 20–249 Employees That Are Required To Submit Information From OSHA Form 300A

Under proposed § 1904.41(a)(1), establishments that had 20 or more employees at any time during the previous calendar year, and that are classified in an industry listed in appendix A to subpart E, would have been required to electronically submit information from their OSHA Form 300A to OSHA or OSHA's designee once a year. As OSHA explained in the preamble to the NPRM, this proposed provision was essentially the same as the previous requirements. OSHA requested comment on proposed § 1904.41(a)(1) generally.

OSHA did not receive many comments specifically about the proposed continuation of the requirement for certain establishments with 20 or more employees to submit their Form 300A data electronically. The Laborers Health and Safety Fund of North America stated that the proposal for establishments with 20 or more employees in certain high-hazard industries to electronically submit Form 300A data to OSHA “must be a requirement,” and emphasized the value of the data for numerous interested parties (Docket ID 0080). The Communications Workers of America (CWA) urged OSHA to expand the submission requirements for the 300A by requiring all establishments with at least 20 employees to submit information from the Form 300A, instead of limiting the requirement to only those industries on appendix A (Docket ID 0092). In addition, the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) commented on this provision, noting that “the proposed rule lowers the previous threshold that triggers a duty to file with OSHA automatically ( i.e., without any request from OSHA) from 250 or more employees to 20 or more employees, increasing the number of small and independent businesses within the appendix A industries required to submit Form 300A” (Docket ID 0036). However, NFIB's comment appears to misunderstand the previous requirements. As OSHA explained in the preamble to the proposed rule, establishments with 20–249 employees, in industries listed in appendix A, were already required to electronically submit information from their OSHA 300A to OSHA every year (87 FR18535–6). OSHA was not proposing an expansion of this requirement.

Having reviewed the evidence in the record, OSHA has decided to retain the Start Printed Page 47261 requirement for establishments with 20–249 employees to annually submit their Form 300A data to OSHA. As noted by the Laborers Health and Safety Fund of North America and discussed further below, this requirement provides a good deal of useful data to many types of interested parties and should not be displaced. OSHA acknowledges the comments supporting expansion of the previous requirement but notes that expanding the requirement for submission of Form 300A data to all establishments with 20–249 employees that are covered by part 1904 would expand the data collection to a total of about 557,000 establishments with 20–249 employees, according to 2019 County Business Patterns data ( https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/data/datasets.html). In contrast, OSHA estimates that about 463,000 establishments with 20–249 employees in industries that are in appendix A will be required to submit data under the final rule ( https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/data/datasets.html). OSHA does not believe, at this time, that the benefits from the additional data collection would outweigh the disadvantages of the additional time and resources required for compliance.

In the previous regulation, this requirement was at § 1904.41(a)(2). In the final rule, it is at § 1904.41(a)(1)(i). This final rule will not impose any new requirements on establishments with 20–249 employees to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA. All establishments that will be required to electronically submit Form 300A information to OSHA on an annual basis under the final rule are already required to do so.

Additionally, as noted above, OSHA revised the language of this requirement slightly for clarity. Specifically, the previous version referred to establishments with “20 or more employees but fewer than 250 employees[,]” while final § 1904.41(a)(1)(i) refers to establishments with “20–249 employees[.]” These clarifying edits do not change the substantive requirements of the provision.

Similarly, OSHA revised the language of proposed § 1904.41(a)(1) in this final rule for clarity without adding any new requirements for employers. Specifically, proposed § 1904.41(a)(1) would have required establishments with 20 or more employees that are in an industry listed in appendix A of subpart E of part 1904 to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA. The final version of that provision, § 1904.41(a)(1)(i), addresses only establishments with 20–249 employees, because final § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii) addresses establishments with 250 or more employees. This change was made to eliminate the overlap, and potential confusion, that would have resulted if both § 1904.41(a)(1)(i) and § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii) addressed establishments with 250 or more employees.

2. Section 1904.41(a)(1)(ii)—Establishments With 250 or More Employees That Are Required To Submit Information From OSHA Form 300A

Although OSHA proposed to maintain the same Form 300A submission requirement for establishments with 20–249 employees, the agency proposed to remove the electronic submission requirement for certain establishments with 250 or more employees. Under previous § 1904.41(a)(1), all establishments of this size in industries routinely required to keep injury and illness records were required to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA once a year. The proposal would have required this submission only from those establishments with 250 or more employees in industries listed in appendix A to subpart E. As explained in the preamble to the proposed rule, OSHA had preliminarily determined that collecting Form 300A data from a relatively small number of large establishments in lower-hazard industries was not a priority for OSHA inspection targeting or compliance assistance activities. OSHA asked for comment on the proposed changes to § 1904.41(a)(1) generally, and also specifically asked the question, “Is it appropriate for OSHA to remove the requirement for establishments with 250 or more employees, in industries not included in appendix A, to submit the information from their OSHA Form 300A?” (87 FR18546).

There were no comments specifically supporting the proposal to remove the requirement for establishments with 250 or more employees, in industries not included in appendix A, to submit the information from their OSHA Form 300A. In contrast, multiple commenters opposed the proposal and urged OSHA to retain the existing requirement for establishments with 250 or more employees that are normally required to report under part 1904 to submit data from their 300As ( e.g., Docket IDs 0024, 0035, Attachment 2, 0039, 0040, 0045, 0047, 0048, 0049, 0051, 0061, 0066, 0067, 0069, 0079, 0080, 0083, 0089, 0092, 0093). Reasons for objecting to the proposed removal of the requirement for some large establishments to submit data from their Form 300As included: OSHA offered no compelling reason for removal; the need for continued oversight over large establishments in lower-hazard industries in general and certain industries in particular; the ability to use the data to protect the large number of employees employed in these establishments; and the value of the public information to employee safety and health efforts.

Some commenters argued that OSHA had not made a persuasive case for removing the requirement for large establishments in industries not listed on appendix A to submit their 300A data. For example, Hunter Cisiewski commented, “The proposed rule ultimately fails to present a compelling argument for why `lower hazard' industries should no longer be required to electronically submit Form 300A when they must still keep record of the form, present it to employees on request, and post it publicly in the workplace” (Docket ID 0024). The AFL–CIO argued, “There is no reason that these establishments should be excluded from a standard they are already subject to and have been complying with. OSHA should at minimum, maintain the requirements for large establishments in these sectors that are already in place” (Docket ID 0061; see also Docket ID 0079). Similarly, Public Citizen and the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW) noted that there would be no significant burden on employers to maintaining the requirement because these employers are already required to keep Form 300A data and they have systems in place for submitting the data to OSHA electronically (Docket IDs 0093, 0066). The United Steelworkers Union (USW) argued that keeping industries covered helps increase the stability of the system. USW urged OSHA to “focus on expanding, not limiting, those covered by disclosure requirements, and to ensure that all employers currently covered by the reporting requirements remain covered” (Docket ID 0067; see also Docket ID 0080). The UFCW stated that “[A]ll available evidence reflects that OSHA's current requirements provide easy access to important data that is crucial to reducing and preventing workplace injuries and illnesses” (Docket ID 0066).

Other commenters, such as the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, noted that although the industries that are not listed in appendix A may have Start Printed Page 47262 relatively low injury rates overall, “injury rates can vary greatly across employers and establishments within industries. The requirement for large establishments to submit a 300A Log annually would be a reasonable way to identify establishments that have high injury rates for their industry, and to identify subsegments of industries that may have more hazardous work processes and activities” (Docket ID 0035, Attachment 2; see also Docket ID 0083). Similarly, the Seventeen Attorneys General from New Jersey, California, Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Vermont (Seventeen AGs) noted their states' concern that removing the 300A submission requirement for “lower-hazard” industries would leave Federal OSHA and State occupational safety and health agencies with little way of determining whether these industries were becoming more dangerous for workers over time. This, in turn, could affect the States' outreach and enforcement efforts. “For example, if [s]tates had previously conducted enforcement and outreach in `low hazard' industries, thus keeping risks down, but deprioritize such enforcement based on a lack of reporting, any uptick of illnesses and injuries in those industries, requiring enforcement efforts, may initially go unnoticed by the [s]tates” (Docket ID 0045).

Other commenters emphasized the significant number of workers employed by the large establishments that OSHA had proposed to exclude from submitting their 300A data, and the usefulness of the data in providing them with safe work environments. Hunter Cisiewski estimated that at least 666,250 workers are employed by the approximately 2,665 establishments with 250 or more employees that were proposed to be removed from the Form 300A submission requirement (assuming that each establishment employs only 250 workers). The same commenter also noted that the workers in these large establishments already rely on the required reporting of their injuries to OSHA “to ensure compliance with workplace regulations” (Docket ID 0024). Similarly, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) noted that even if the industries proposed for exclusion have lower injury and illness rates than the industries on appendix A, they employ a large number of people. “Numbers [of workers] as well as rates of work-related injuries or illness need to be considered in setting prevention priorities. These establishments need to provide a safe work environment, and electronic collection of summary data will allow OSHA and public health agencies to monitor their ability to do so” (Docket ID 0040). The International Brotherhood of Teamsters commented, “we think continuing to collect OSHA 300A data for the large numbers of workers employed in these establishments, would help to identify less obvious problems and implement corresponding preventive measures” (Docket ID 0083).

Various commenters pointed to known or potentially hazardous industry segments that would have been exempt from submitting 300A data under the proposal. For example, the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (National COSH) as well as the Centro de los Derechos del Migrantes pointed to the temporary service industry and the home health care industry as industries with known hazards for which OSHA and the public should have access to injury and illness data (Docket IDs 0048, 0089; see also Docket ID 0049). The AFL–CIO pointed to home health services, an industry heavily affected by COVID–19, employment services, which includes vulnerable temporary workers, and some wholesalers with rates of cases with days away from work, restricted work activity, or job transfer (DART) above 2.0 per 10,000 workers in 2020 ( e.g., NAICS 4231, 4233, 4235, 423930, 4244, 4248, 4249) as industries containing large establishments that would be newly exempted from the 300A submission requirements The AFL–CIO argued that “limiting the data these industries provide the agency would severely limit the ability to track and identify emerging workplace hazards” (Docket ID 0061).

Some commenters argued that maintaining the existing 300A reporting requirement for all large establishments is particularly important because the industries on appendix A reflect injury and illness data from the BLS SOII that is not current. Therefore, exempting industries not on appendix A could result in missing information from industries that may have become more dangerous since publication of the SOII data for 2011 to 2013. The United Steelworkers Union (USW) commented, “By tying the proposed rule to outdated and underreported injury and illness data, many employers with 250 or more employees in potentially high-hazard industries would be exempted, limiting workers' ability to make informed decisions about a workplace's safety and health. . . . These industries are currently covered by reporting requirements and many, like home health, have seen a rise in injuries and illnesses since the COVID–19 pandemic began” (Docket ID 0067). Public Citizen echoed this comment, stating that past injury rates, which are used to designate industries required to submit data, may not reflect more recent safety conditions. Public Citizen noted, in addition, that the pandemic served as a reminder “that even seemingly `low-hazard' workplaces can be the epicenter of deadly outbreaks” (Docket ID 0093).

Finally, a number of commenters underscored the value of the 300A data that is being collected from large establishments. The UFCW urged OSHA to retain the requirement for collection from all large establishments because it would allow many types of users (the public, employers, workers, researchers, and the government) to use the data “in the very positive ways that the UFCW has used it” already. The UFCW described, in its comment, the many specific ways in which UFCW has used published and union-collected illness and injury data from the OSHA Form 300A, among other information, to increase safety and health at large union-represented facilities (Docket ID 0066). Public Citizen commented that “the value of continuing to collect the information from these employers outweighs any supposed burden . . . data collected from electronic submission of injury and illness information can help identify broad patterns from small injury and illness numbers per establishment. Having this additional data from Form 300A summaries would assist with research into specific types of injuries and illnesses” (Docket ID 0093).

In addition to supporting maintenance of the requirement for submission of 300A data by large establishments, several commenters supported expanding the submission requirements for large establishments even further. For example, the National Employment Law Project (NELP) supported requiring all employers with 250 or more employees to submit information from the Form 300 Log in addition to the Form 300A. NELP argued that certain industries, such as home health care and employment services, contain very large employers that have Total Case Rates (TCRs) that are well above the private sector average. NELP therefore urged OSHA to retain as well as expand electronic submission requirements for large establishments with 250 or more employees in industries that are required to keep records under part 1904 so that researchers and other Start Printed Page 47263 organizations could more effectively track and monitor occupational health and safety trends in home health care, employment services, and other sectors (Docket ID 0049; see also Docket ID 0089).

The Laborers' Health and Safety Fund of North America argued that OSHA should require all establishments with 250 or more employees to submit the Form 300 and Form 301, in addition to the Form 300A: “Establishments with 250 or more employees account for large contractors that work on larger construction sites that can be considered high-risk. For these reasons, establishments should be required to submit electronic OSHA 300, 300A and 301 forms to not only track injury and illness, but prove to OSHA that they are taking the steps to mitigate and prevent them from happening” (Docket ID 0080).

Having reviewed the information in the record on this issue, OSHA has decided not to make the proposed change of restricting the universe of large establishments that are required to submit data from Form 300A. Instead, the agency will maintain the requirement for all establishments with 250 or more employees that are covered by part 1904 to submit the information from their OSHA Form 300A to OSHA, or its designee, once a year. As explained by commenters, these establishments are already submitting this information, so there is no new burden for employers. Furthermore, access to the information provides multiple benefits for workers, Federal and State occupational safety and health agencies, and other interested parties. For example, continuing to collect and make this data available to the public will allow tracking of industry hazards over time, even for industries that are not on appendix A. Commenters noted that this type of tracking was particularly critical for industry segments and establishments that have injury rates higher than the rate for their 4-digit NAICS industry overall. They also noted that requiring information to be submitted from all large establishments will help blunt the effect of using SOII data that is several years old in determining which NAICS will be included on appendix A. OSHA agrees with these rationales.

Although OSHA stated in the proposal that collecting Form 300A data from this relatively small number of large establishments in lower-hazard industries is not a priority for OSHA inspection targeting or compliance assistance, OSHA is persuaded by commenters who see the value in providing such data to the public; this includes the UFCW, which has been using this data to make positive safety and health changes in large establishments. In addition, OSHA recognizes the large number of workers represented by the relatively small number of establishments that would have been affected by the proposed change and does not wish to remove resources that could be used to improve their safety and health.

OSHA acknowledges the comments supporting expansion of the final requirement by requiring submission of information from Forms 300 and 301 by all large establishments (250 or more employees) required to keep records under part 1904. However, this change would expand the universe of large establishments required to submit Form 300 and Form 301 data from about 22,000 (establishments with at least 250 employees that are in NAICS listed on appendix B) to about 40,000 (establishments with at least 250 employees that are required to keep records under part 1904), an increase of 80 percent (data are as of 2019; see https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/data/datasets.html). OSHA does not believe, at this time, that the benefits from the additional data collection would outweigh the disadvantages of the additional time and resources that employers would have to expend to comply. OSHA also values the stability provided to employers by keeping the universe of establishments required to submit 300A data the same, in light of the multiple recent changes to OSHA's data submission requirements.

In the previous regulation, this requirement was at § 1904.41(a)(1). In the final rule, it is at § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii). This final rule will not impose any new requirements on establishments to electronically submit information from their Form 300A to OSHA. All establishments that will be required to electronically submit Form 300A information to OSHA on an annual basis under the final rule were already required to do so under the previous regulation. OSHA made only one non-substantive change in the final regulatory text; whereas the previous regulatory text at § 1904.41(a)(1) contained an example stating that data for calendar year 2018 would be submitted by the month and day listed in § 1904.41(c) of calendar year 2019, that example has been removed from the final regulatory provision at § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii). A similar, updated example is included in final § 1904.41(b)(1).

3. Restructuring of Previous Section 1904.41(a)(1) and (2) Into Final Section 1904.41(a)(1)(i) and (ii)

In the preamble to the proposed rule, OSHA asked the following question about the structure of the regulatory text containing the requirements to submit data from OSHA injury and illness recordkeeping forms: “The proposed regulatory text is structured as follows: § 1904.41(a)(1) Annual electronic submission of information from OSHA Form 300A Summary of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses by establishments with 20 or more employees in designated industries; § 1904.41(a)(2) Annual electronic submission of information from OSHA Form 300 Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses, OSHA Form 301 Injury and Illness Incident Report, and OSHA Form 300A Summary of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses by establishments with 100 or more employees in designated industries. This is the structure used by the 2016 and 2019 rulemakings. An alternative structure would be as follows: § 1904.41(a)(1) Annual electronic submission of information from OSHA Form 300A Summary of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses by establishments with 20 or more employees in designated industries; § 1904.41(a)(2) Annual electronic submission of information from OSHA Form 300 Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses and OSHA Form 301 Injury and Illness Incident Report by establishments with 100 or more employees in designated industries. Which structure would result in better understanding of the requirements by employers?” (87 FR 18547).

OSHA did not receive many comments on this proposed alternative structure for the regulatory text. However, NIOSH noted that it preferred the second option. “NIOSH finds the second alternative . . . to be somewhat preferable. That alternative focuses first on which establishments are required to submit OSHA Form 300A, and then focuses on which establishments are required to submit OSHA Forms 300 and 301. This structure may help employers to more directly answer their questions about what forms to submit” (Docket ID 0035, Attachment 2).

OSHA agrees that the proposed alternative structure, which separates the provisions by recordkeeping form, may help employers better understand the regulatory requirements for their establishments. Based on this reasoning, as well as on OSHA's decision to retain the requirement for all establishments with 250 or more employees in industries covered by part 1904 to Start Printed Page 47264 submit information from their Form 300A annual summary (discussed above), OSHA has decided to restructure the final regulation by recordkeeping form, rather than establishment size and industry. Therefore, in the final rule, § 1904.41(a)(1) covers the requirement to submit the OSHA Form 300A, with § 1904.41(a)(1)(i) for establishments with 20–249 employees in appendix A industries, and § 1904.41(a)(1)(ii) for establishments with 250 or more employees in industries covered by part 1904. Final § 1904.41(a)(2) covers the requirement to submit the OSHA Forms 300 and 301, as discussed below.

4. Updating Appendix A

Additionally, OSHA proposed to revise appendix A to subpart E to update the list of designated industries to conform with the 2017 version of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Since OSHA revised § 1904.41 in 2016, the Office of Management and Budget has issued two updates to the NAICS codes, in 2017 and 2022. As explained in the preamble to the proposed rule, OSHA believed that the proposed update from 2012 NAICS to 2017 NAICS would have the benefits of using more current NAICS codes, ensuring that both proposed appendix A and proposed appendix B used the same version of NAICS, aligning with the version currently used by BLS for the SOII data that OSHA used for this rulemaking, and increasing the likelihood that employers were familiar with the industry codes.

As OSHA explained, this revision would not affect which industries were required to provide their data, but rather simply reflect the updated 2017 NAICS codes. For appendix A, OSHA limited the scope of this rulemaking to the proposed update from the 2012 version of NAICS to the 2017 version of NAICS. The change from the 2012 NAICS to the 2017 NAICS would affect only a few industry groups at the 4-digit NAICS level. Specifically, the 2012 NAICS industry group 4521 (Department Stores) is split between the 2017 NAICS industry groups 4522 (Department Stores) and 4523 (General Merchandise Stores, including Warehouse Clubs and Supercenters). Also, the 2012 NAICS industry group 4529 (Other General Merchandise Stores) is included in 2017 NAICS industry group 4523 (General Merchandise Stores, including Warehouse Clubs and Supercenters). As noted above, however, the establishments in these industries were already covered by the previous record submission requirements, so this would not represent a substantive change in those requirements.

The Phylmar Regulatory Roundtable (PRR) supported the proposed update from the 2012 version of NAICS to the 2017 version of NAICS for appendix A, commenting, “It is both practical and logical to align with the most recent codes from an accuracy standpoint” (Docket ID 0094). The Coalition for Workplace Safety (CWS), on the other hand, commented that using the 2017 NAICS codes for Appendices A and B when the 2022 codes have already been released by OMB will lead to confusion and mistakes, unduly complicating the proposed requirements (Docket ID 0058).

While OSHA did not propose modifications to appendix A other than the update from 2012 NAICS to 2017 NAICS, OSHA did discuss one alternative in the proposal that would affect the industries on appendix A: updating appendix A to reflect the 2017–2019 injury rates from the SOII. Appendix A is based on the SOII's injury rates from 2011–2013. This alternative would have resulted in the addition of one industry to appendix A (NAICS 4831 (Deep sea, coastal, and great lakes water transportation)) and the removal of 13 industries (4421 Furniture Stores, 4452 Specialty Food Stores, 4853 Taxi and Limousine Service, 4855 Charter Bus Industry, 5152 Cable and Other Subscription Programming, 5311 Lessors of Real Estate, 5321 Automotive Equipment Rental and Leasing, 5323 General Rental Centers, 6242 Community Food and Housing, and Emergency and Other Relief Services, 7132 Gambling Industries, 7212 RV (Recreational Vehicle) Parks and Recreational Camps, 7223 Special Food Services, and 8113 Commercial and Industrial Machinery and Equipment (except Automotive and Electronic) Repair and Maintenance).

OSHA did not receive many comments in response to this alternative. The AFL–CIO stated that the use of “outdated” SOII data to determine the industries on appendix A would lead to missing information from industries that might have become (or might become in the future) more hazardous since the time period used as the basis for appendix A (2011–2013). However, this statement was made in the context of the AFL–CIO's argument that OSHA should not restrict the large establishments required to submit 300A data to those in industries on appendix A, as OSHA proposed. Because OSHA is not adopting that approach, and instead is requiring all large establishments covered by part 1904 to continue submitting data from Form 300A, OSHA believes this concern will be minimized under the final regulatory requirements.

Having reviewed the record, OSHA has decided to update appendix A to subpart E from the 2012 version of NAICS to the 2017 version of NAICS. As the PRR commented, it is practical and logical to align the industry list in appendix A with the more recent NAICS codes (see Docket ID 0094). Indeed, employers are likely more familiar with the 2017 codes than the 2012 codes. This change would also ensure that appendices A and B use the same version of NAICS. Finally, the 2017 NAICS codes are used by BLS for the SOII data that OSHA is using for this rulemaking. While CWS stated that using the 2017 codes when the 2022 codes have already been released will cause confusion (Docket ID 0058), OSHA notes that both appendices are based on SOII data from BLS, and that no SOII data using the 2022 NAICS codes are currently available. SOII data for 2022 will not be available until November 2023. Thus, it is not possible for OSHA to base appendix A or B on SOII data that use the 2022 NAICS codes, even though the 2022 codes are the most recent ones available.

OSHA has also decided not to update appendix A using more recent SOII data. As discussed in the preamble to the proposed rule, it took several years for the regulated community to understand which industries were and were not required to submit information, and such misunderstandings could result in both underreporting and overreporting. OSHA has determined that changing the covered industries, by changing the data that forms the basis for the NAICS on appendix A, would result in additional confusion for the regulated community that is not warranted at this time. Moreover, three of the industries that would be removed from appendix A if OSHA based that appendix on updated data are also listed in appendix B, indicating that they remain hazardous under other measures. Finally, as noted above, OSHA agrees with interested parties who commented that requiring information to be submitted from all large establishments will help blunt the effect of using the older SOII data in determining which NAICS will be included on appendix A.

The final appendix A to subpart E of part 1904 (Designated industries for § 1904.41(a)(1)(i) Annual electronic submission of information from OSHA Form 300A Summary of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses by establishments Start Printed Page 47265 with 20–249 employees in designated industries) is as follows: [3]