-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 41726

AGENCY:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), issues this final rule to provide clarity and safeguards that address the public health risk of dog-maintained rabies virus variant (DMRVV) associated with the importation of dogs into the United States. This final rule addresses the importation of cats as part of overall changes to the regulations affecting both dogs and cats, but the final rule does not require that imported cats be accompanied by proof of rabies vaccination and does not substantively change how cats are imported into the United States.

DATES:

This final rule is effective August 1, 2024.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Ashley C. Altenburger, J.D., Division of Global Migration Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, MS H16-4, Atlanta, GA 30329. Telephone: 1-800-232-4636. For information regarding CDC operations and importations: Dr. Emily Pieracci, D.V.M., Division of Global Migration Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road NE, MS H16-4, Atlanta, GA 30329; Telephone: 1-800-232-4636.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

This rule is organized as follows:

I. Executive Summary

a. Purpose of This Regulatory Action

b. Summary of Major Provisions

c. Costs and Benefits

II. Public Participation

III. Background

a. Legal Authority

b. Regulatory History

IV. Summary of the Final Rule

V. Alternatives Considered

VI. Summary of Public Comment and Responses

VII. Required Regulatory Analyses

a. Executive Orders 12866, 13563, and 14094

b. The Regulatory Flexibility Act

c. The Paperwork Reduction Act

d. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

e. Executive Order 12988: Civil Justice Reform

f. Executive Order 13132: Federalism

g. The Plain Language Act of 2010

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose of This Regulatory Action

Through this final rule, HHS/CDC is revising its regulation at 42 CFR 71.51 to prevent the reintroduction and spread of dog-maintained rabies virus variant (DMRVV) in the United States. HHS/CDC is also revising 42 CFR 71.50, which contains definitions applicable to animal importations under 42 CFR part 71, subpart F. The United States was declared DMRVV-free in 2007.[1] The importation of just one dog infected with DMRVV risks re-introduction of the virus into the United States; such a public health threat could result in the loss of human and animal life and consequential economic impact.[2 3 4] The rabies virus can infect any mammal, and, once clinical signs appear, the disease is almost always fatal.[5] A DMRVV-infected dog can transmit the virus to humans, domestic pets, livestock, or wildlife. Importing inadequately vaccinated dogs from countries at high risk of DMRVV (high-risk countries) [6] involves a significant public health risk to people who directly interact with those dogs. This rule also includes requirements for dogs from DMRVV-free and low-risk countries to confirm that the dog has not been in a high-risk country during the six months before arriving in the United States. In 2019, the importation of a DMRVV-infected dog cost the affected State governments more than $400,000 U.S. dollars (USD) for the ensuing public health investigations and rabies post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) treatments administered to exposed persons.[7 8]

Through this final rule, HHS/CDC also seeks to prevent and deter the importation of dogs with falsified or fraudulent rabies vaccine documentation. In 2020, CDC observed a 52 percent increase in the number of dogs that were ineligible for admission due to falsified or fraudulent documentation, as compared to 2018 and 2019 (450 dogs compared to the previous baseline of 300 dogs per year out of an estimated 32,530 foreign-vaccinated dogs arriving annually from DMRVV high-risk countries as reported in Section VIIA).[9 10] This troubling trend continued from January through June 2021, prior to the implementation of the temporary suspension in July 2021,[11] with an additional 24 percent increase of dogs ineligible for admission in just the first half of the year, compared to the full 2020 calendar year (January-December) (approximately 560 dogs with falsified or fraudulent documentation).[12] This final rule will also support CDC's efforts to improve data collection related to dog importation, including tracking the total number of dog importations which CDC has been unable to do previously across all ports and for all importations.

The use of a single false rabies vaccination certificate (RVC) [13] or other rabies vaccination document as part of a larger shipment of multiple dogs raises suspicion that the rabies vaccination documents for the remaining dogs may also be false. This is not an uncommon occurrence [14] and creates an additional Start Printed Page 41727 burden on CDC and State health departments to track, test, and evaluate the remaining dogs in the shipment.

CDC has documented numerous importations every year in which flight parents [15 16] transport dogs for the purpose of resale, adoption, or transfer of ownership that do not meet CDC's entry requirements. These flight parents often claim the dogs are their personal pets to avoid U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal Care [17] entry requirements and potential tariffs or fees under CBP regulations. Even when well-meaning, these importers jeopardize public health, as many of them do not know the history of the animals they are transporting. Deterring individuals who serve as flight parents from supporting fraudulent dog importations has proven difficult despite the existence of CBP penalties relating to aiding unlawful importations and fraudulent conduct. See19 U.S.C. 1592 and 19 U.S.C. 1595a.

The documented increase in fraudulent vaccine documentation and importers circumventing dog import regulations was shortly followed by the emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Many public health resources were redirected to the COVID-19 response, reducing the availability of resources to respond to dog importation issues. In light of this confluence of events, in June 2021, CDC published a temporary suspension of dogs entering the United States from DMRVV high-risk countries.[18] The temporary suspension created a system that, among other things, implemented the use of standardized forms, required test results demonstrating the presence of rabies antibodies in dogs, and developed a network of animal care facilities authorized by CDC for the purpose of allowing for the immediate quarantine of dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries arriving with inadequate proof of test results. During the temporary suspension, CDC has documented decreased instances of fraud, fewer dogs being denied admission into the country, and fewer sick and dead dogs arriving in the United States from both DMRVV high-risk and DMRVV-free and low-risk countries, all of which have resulted in fewer Federal and State agency resources devoted to addressing issues related to inadequate rabies vaccination and/or documentation. This final rule implements a similar regulatory framework, expanded to dogs from DMRVV-free and low-risk countries, based on the documented successes of the temporary suspension.

B. Summary of Major Provisions

In this final rule, HHS/CDC aligns U.S. import requirements for dogs with the importation requirements of other DMRVV-free countries by requiring proof of rabies vaccination and adequate serologic test results from a CDC-approved laboratory. The final rule requires for all dog imports: a microchip, six-month minimum age requirement for admission, and importer submission of a CDC import form ( CDC Dog Import Form). The rule requires airlines to confirm documentation, provide safe housing for animals, and assist public health officials in determining cause of animal illness or death.

B.i. Requirements for All Dogs

Per this final rule, HHS/CDC requires that all dogs arriving from any country, including dogs returning to the United States after traveling abroad, be microchipped with an International Standards Organization (ISO)-compatible microchip prior to travel into the United States. The microchip information must be included on importation documents to help ensure that dogs presented for admission are the same dogs as those listed on the rabies vaccination records or other documents. CDC has documented several instances of importers attempting to present records of vaccinated dogs as the vaccination records for dogs that lacked appropriate veterinary paperwork in an attempt to import the unvaccinated dogs into the United States without detection.[19] Because microchips were not required for entry into the United States at that time and the dogs in question were not microchipped, the public health investigations to confirm the identity of those dogs were both resource-intensive and challenging. Microchips are used frequently by pet owners and required for international transit by many foreign countries, including for importation in many DMRVV-free countries. Microchips are also recommended by the international veterinary community and animal rescue and welfare organizations to reunite lost animals with their owners and ensure that the veterinary records for an animal can be linked to the animal.[20] Further, during CDC's temporary suspension of dogs entering the United States from DMRVV high-risk countries, CDC documented that 99 percent (>20,000) of permit applications received were for dogs that had microchips implanted prior to the announcement of the suspension. Therefore, CDC's requirement has minimal impact on dog importations, although costs to some importers may still be incurred.

To address concerns about importations of puppies that are too young to be properly vaccinated against rabies, through this final rule, HHS/CDC requires that any dog arriving in the United States be at least six months of age. Dogs cannot be vaccinated effectively against rabies before 12 weeks of age and are not considered fully vaccinated until 28 days after vaccination.[21] Establishing a six-month minimum age requirement for the import of dogs aligns with current USDA requirements for commercial dog imports under the Animal Welfare Act and will better protect the public's health from rabies.[22]

In this final rule, HHS/CDC also requires all dog importers to submit a CDC Dog Import Form ( i.e., an online form that includes the importers' contact information and information related to each dog being imported) via a CDC-approved system prior to travel to the United States. This requirement would apply to all imported dogs (including dogs arriving from DMRVV-free and DMRVV low-risk countries) arriving in the United States by air, land, or sea. Upon arrival at a U.S. port, importers must present a receipt confirming they submitted a completed CDC Dog Import Form; additionally, importers arriving by air must present the receipt to the airline prior to boarding. The receipt contains the information submitted on the CDC Dog Start Printed Page 41728 Import Form, which allows government officials to verify that the details from the CDC Dog Import Form match the dog being presented for entry. CDC's import submission system is a free online system. Requiring documentation for all imported dogs allows CDC to track the total number of dog importations (including the number imported from DMRVV high-risk countries), something CDC has been unable to do previously.

To improve vaccination verification systems and deter fraud, CDC's required forms (not including the electronically submitted CDC Dog Import Form ) need to be endorsed by official government veterinarians in the country of export. Importers should contact their local veterinarian who can submit the required form to an official government veterinarian in the exporting country. Importers may also use the USDA pet travel website or IPATA website to contact a pet shipper to request assistance.[23 24]

All dogs arriving by air are required to have an air waybill (AWB). An AWB is a legally binding document issued by a carrier to a shipper or importer that details the type, quantity, and destination of the goods ( i.e., dogs) being carried. It serves as a tracking number that can assist Federal agencies in monitoring the dog throughout the lifecycle of the dog's travel from the point of origin to the final destination. Additionally, a bill of lading serves as undisputed proof of shipment, and it represents the agreed upon terms and conditions for the transportation of the goods. All commercial airlines and many private cargo aircraft are capable of generating AWB. Additionally, CDC has successfully piloted the generation of AWB for dogs transported as hand-carried or excess baggage with several foreign air carriers during the temporary suspension to ensure air carriers can generate AWB for dogs transported as hand-carried or excess baggage.

B.ii. Requirements for Dogs From DMRVV-Free or DMRVV Low-Risk Countries

This final rule further permits dogs imported from DMRVV-free or DMRVV low-risk countries to arrive at any U.S. port.[25] In lieu of a CDC vaccination form, which is required for dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries, these importers may instead provide proof (examples outlined in paragraph (u)) that the dogs have been in DMRVV-free or DMRVV low-risk countries only during the six months prior to arriving in the United States.

TB.iii. Requirements for Dogs From DMRVV High-Risk Countries

Per this final rule, HHS/CDC requires all importers of dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months, regardless of whether foreign- or U.S.-vaccinated, to submit a standardized vaccination form verifying the rabies vaccination status of the dog. This final rule permits dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country in the past six months and have a valid U.S.-issued rabies vaccination form to arrive at any U.S. port. For dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country in the past six months, and were vaccinated in a foreign country, this final rule requires that the dog arrive at a U.S. airport with a CDC quarantine station (also known as a port health station) and a CDC-registered animal care facility (ACF).

HHS/CDC is removing the current requirement for a valid RVC in 42 CFR 71.51(c) and replacing it with new rabies vaccination forms for dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries. The rabies vaccination forms include the rabies vaccination status of the dog and other required information similar to the previous valid RVC requirement. However, unlike the previous requirement for a valid RVC, the rabies vaccination forms are standardized.

The rabies vaccination form for foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries must also be endorsed by a government official in the exporting country, as an added measure to prevent falsification. The name for the rabies vaccination form to fulfill this requirement for foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries was shortened from CDC Import Certification of Rabies Vaccination and Microchip Required for Live Dog Importations into the United States as proposed in the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) to Certification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip. The requirement for this standardized form helps ensure that foreign-vaccinated dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries meet CDC entry requirements prior to traveling to the United States and allows for follow-up with the exporting country's government officials if repeated import violations occur.

Under this final rule, importers of U.S.-vaccinated dogs, including dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months, may arrive at any U.S. port. Prior to traveling out of the United States with a U.S.-vaccinated dog that will be present in a DMRVV high-risk country, the dog owner must obtain a form titled Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination that must be completed and signed by a USDA-Accredited Veterinarian. The name for this rabies vaccination form was shortened from Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination for Live Dog Re-entry into the United States as proposed in the NPRM to Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination. CDC is partnering with USDA to utilize the USDA export process to verify an animal was vaccinated in the United States. This form must be endorsed by a USDA Official Veterinarian prior to the dog's departing the United States and must be presented by the importer to the airline to board the dog on its return flight to the United States. The importer must also present this form when requested to do so by U.S. government officials upon arrival. By having USDA-accredited veterinarians certify documents before export from the United States, CDC can confirm the dogs were previously vaccinated in the United States. The use of this form decreases the likelihood of missing or incomplete vaccination documentation because it includes all required information in a standardized format and relies on USDA's existing veterinary accreditation system for animal exportation. This form will also reduce instances of fraud or falsification because it can be verified by any U.S. government agency online through USDA's website after the USDA official veterinarian certifies the document. Dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries arriving with this form are not subject to the requirement for veterinary examination (unless ill, injured, or exposed), revaccination, confirmation of adequate rabies serologic tests, and/or post-vaccination quarantine at a CDC-registered ACF.

HHS/CDC is requiring importers of foreign-vaccinated dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months to enter the United States through an airport with a CDC quarantine station and a CDC-registered ACF. The importer must have a reservation at the CDC-registered ACF and have their dog(s) undergo a veterinary exam and revaccination with a USDA-licensed rabies vaccine at the CDC-registered ACF. The importer must obtain a rabies serologic test from a CDC-approved laboratory for their foreign-vaccinated dogs demonstrating adequate titer levels. Importers of foreign-vaccinated dogs that have been Start Printed Page 41729 in a DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months who cannot obtain serologic test results prior to importation are required to have their dog remain under quarantine at the facility for 28 days after revaccination or until confirmation of adequate rabies serologic test from a CDC-approved laboratory is obtained, whichever occurs first.

CDC is requiring the use of CDC-registered ACF as opposed to community veterinary clinics because (1) ACF are trained to quarantine animals, and to observe and report abnormalities in quarantined animals to CDC; (2) ACF undergo, at a minimum, an annual inspection to ensure compliance with CDC regulations; (3) ACF are experienced in pet transportation and trained to meet requirements established by airlines, exporting countries, and U.S. importation requirements; and (4) ACF are bonded facilities that have special equipment and insurance for goods ( i.e., dogs) that are awaiting clearance into the United States.

B.iv. Exemption for Foreign-Vaccinated Service Dogs at U.S. Seaports

In this final rule, HHS/CDC is allowing foreign-vaccinated service dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months to enter the U.S. at a U.S. seaport if the dog is at least six months of age; has a microchip; has a complete, accurate, and valid Certification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip form; and has sufficient and valid titer results from a CDC-approved laboratory. To be considered a valid service dog, the dog must meet the definition of a “service animal” [26] under 14 CFR 382.3 and accompany an “individual with a disability” [27] as defined under 14 CFR 382.3. This exemption is limited to foreign-vaccinated service dogs entering the United States via seaports and is not available to foreign vaccinated dogs entering via air or at land ports. Under this final rule, airlines must confirm that foreign vaccinated dogs, including foreign vaccinated service dogs meet all CDC requirements prior to allowing dogs to board an aircraft. Therefore, CDC had determined that a special exemption for foreign-vaccinated service dogs arriving via air is not needed because airlines must confirm that these dogs meet all CDC requirements prior to arrival. Under such circumstances, an individual with a disability can choose to remain with their service animal and seek to rebook their flights after all CDC requirements have been met. Similarly, CDC has determined that a special exemption for foreign vaccinated service dogs is not needed at land ports because if the dogs do not meet all CDC requirements for entry, the dogs will be denied entry to the United States. Under these circumstances, the individual can choose to remain with their dogs on the non-U.S. side of the land border and then seek admission after all CDC requirements have been met. CDC further notes that there are fewer available ACFs close to land ports and allowing an exemption for foreign vaccinated service animals at land ports would be operationally impracticable. Regarding the exemption for service animals entering via seaports, CDC believes that this exemption would most likely be used by individuals with disabilities traveling with their service animals on board cruise ships and that these individuals would presumably be visiting the United States for a very short period of time before reboarding the ship ( e.g., under circumstances where an individual with a disability is participating on a shore excursion). Based on the limited amount of time that these service animals will be spending in the United States and the fact that cruise operators maintain their own vaccination requirements for service dogs, CDC believes that the rabies risk presented by foreign-vaccinated service dogs temporarily visiting the United States via cruise ship is low. The volume of foreign-vaccinated service dogs arriving from high-risk countries on board non-cruise sea vessels is also believed to be very small, compared to the number of foreign-vaccinated service dogs arriving from high-risk countries entering the US via land and air which presents a greater public health risk and the need for enforcement of the requirements without an exemption.

B.v. Requirements for Dogs From DMRVV-Restricted Countries

The final rule also authorizes HHS/CDC to prohibit or otherwise restrict the importation of dogs into the United States from certain countries that have a history of exporting dogs infected with DMRVV or have demonstrated a lack of appropriate veterinary controls to prevent the exportation of rabid dogs. HHS/CDC will maintain a “List of DMRVV-Restricted Countries” from which the importation of dogs into the United States would be prohibited on CDC's website; however, HHS/CDC is not including any countries on this list at this time. Additions or removals of countries will be announced in notices published in the Federal Register and would include a timeline for implementation. CDC retains the ability to allow certain importers to apply for and for CDC to issue CDC Dog Import Permit s on an extremely limited basis for dogs that have been in a DMRVV-restricted country in the six months prior to their importation into the United States ( e.g., for dogs imported for scientific purposes, for use as a service animal for individuals with disabilities,[28] or in furtherance of an important government interest).

B.vi. Requirements for Airlines

The final rule further requires that an airline, prior to accepting a dog for transport, confirm that the dog possess all required import documentation based on the country of origin. Airlines must also ensure that foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries are entering the United States only through a designated U.S. airport with both a CDC quarantine station and a CDC-registered ACF and that the importer possesses a reservation with the CDC-registered ACF for examination, vaccination, and quarantine (if required). Air carriers are required to create bill of lading ( e.g., air waybill (AWB)) for all dogs entering the United States via air, including dogs Start Printed Page 41730 transported as cargo, hand-carried and checked-baggage. As needed, CDC will coordinate with the airline regarding transport of the dog to the CDC-registered ACF. These regulatory actions help ensure that dogs arriving in the United States from DMRVV high-risk countries are adequately protected against rabies and do not pose a public health threat.

The final rule requires that airlines return dogs or cats denied admission to the country of departure within 72 hours after arrival, unless the animal is ill or injured and CDC has approved delaying the return of the animal. The responsibility for a dog or cat pending admission into the United States or awaiting return to the country of departure has been a point of confusion for many airlines, resulting in delayed care and improper housing for numerous animals. Delays in returning dogs to their countries of departure also potentially threaten U.S. public health by exposing people to dogs with unknown rabies vaccination status. HHS/CDC requires that the airline that flew a dog or cat to the United States must arrange for and ensure transportation, housing, and care until the animal is either returned to the county of departure or cleared for entry into the United States.

This final rule also includes a provision regarding dogs and cats that die en route to the United States or that die while detained pending determination of their admissibility. This provision is primarily directed at airlines and requires that they arrange for transportation of deceased dogs and cats and for necropsy requiring gross and histopathologic examination and any subsequent infectious disease testing based on the findings. The importer is responsible for all costs associated with transportation, necropsy and testing and providing the CDC quarantine station [29] with the final necropsy report and all test results. The airline is also required to notify the CDC quarantine station of jurisdiction [30] prior to transporting a dead dog or cat for a necropsy to determine whether rabies testing is required. These measures will help CDC rule out foreign animal diseases of public health concern [31] as a potential cause of death, enable CDC to take responsive measures as needed, and will protect both animal and human health. The provisions of this paragraph may also be applied to other carriers transporting such dogs and cats in the very rare event when the death of a dog or cat occurs en route to the United States, or the animal dies while detained pending determination of admissibility.

The final rule requires airlines to confirm prior to boarding a foreign-vaccinated dog from a DMRVV high-risk country that the dog is scheduled to arrive at an approved U.S. airport and the importer has documentation confirming a reservation at the CDC-registered ACF. This ensures that CDC and USDA can follow up with airlines more easily to confirm animals are being properly handled ( e.g., not left in cargo warehouses for prolonged periods of time that endanger the health of the animal). Additionally, to address concerns relating to the movement of dogs or cats that are sick or dead upon arrival, HHS/CDC requires airlines to arrange transportation of all sick or dead animals (regardless of vaccination status and country of origin) to a CDC-registered ACF or, under certain conditions, to another CDC-approved veterinary clinic as soon as possible.

The final rule requires airlines to transport healthy-appearing animals that are denied admission and awaiting return to their country of departure, or are awaiting a determination as to their admissibility, to a CDC-registered ACF within 12 hours. CDC acknowledges that extraordinary circumstances, such as extreme weather, may delay the transport of animals beyond the 12-hour window. Under such circumstances, CDC will work closely with airlines to address these rare and unforeseen events while ensuring the safe handling of animals. CDC also will work with importers who arrive at unapproved U.S. ports based on circumstances beyond their control ( e.g., re-routing of their flight due to extreme weather). CDC quarantine station staff are available 24 hours a day to assist streamlined coordination and processing of dog and cat importation at U.S. ports and provide coverage for geographic areas beyond the U.S. port in which the CDC quarantine station is located.

B.vii. Other Requirements and Summary

HHS/CDC is establishing requirements for businesses that wish to become CDC-registered ACF. Requirements include a USDA intermediate handlers registration and approved by CBP to act as a CBP-bonded facility with an active Facilities Information and Resource Management System (FIRMS) code. This ensures dogs and cats receive appropriate veterinary care and are housed in a way that prevents the spread of infectious diseases while protecting the safety of the animals. CDC-registered ACF must be located within 35 miles of a CDC quarantine station.

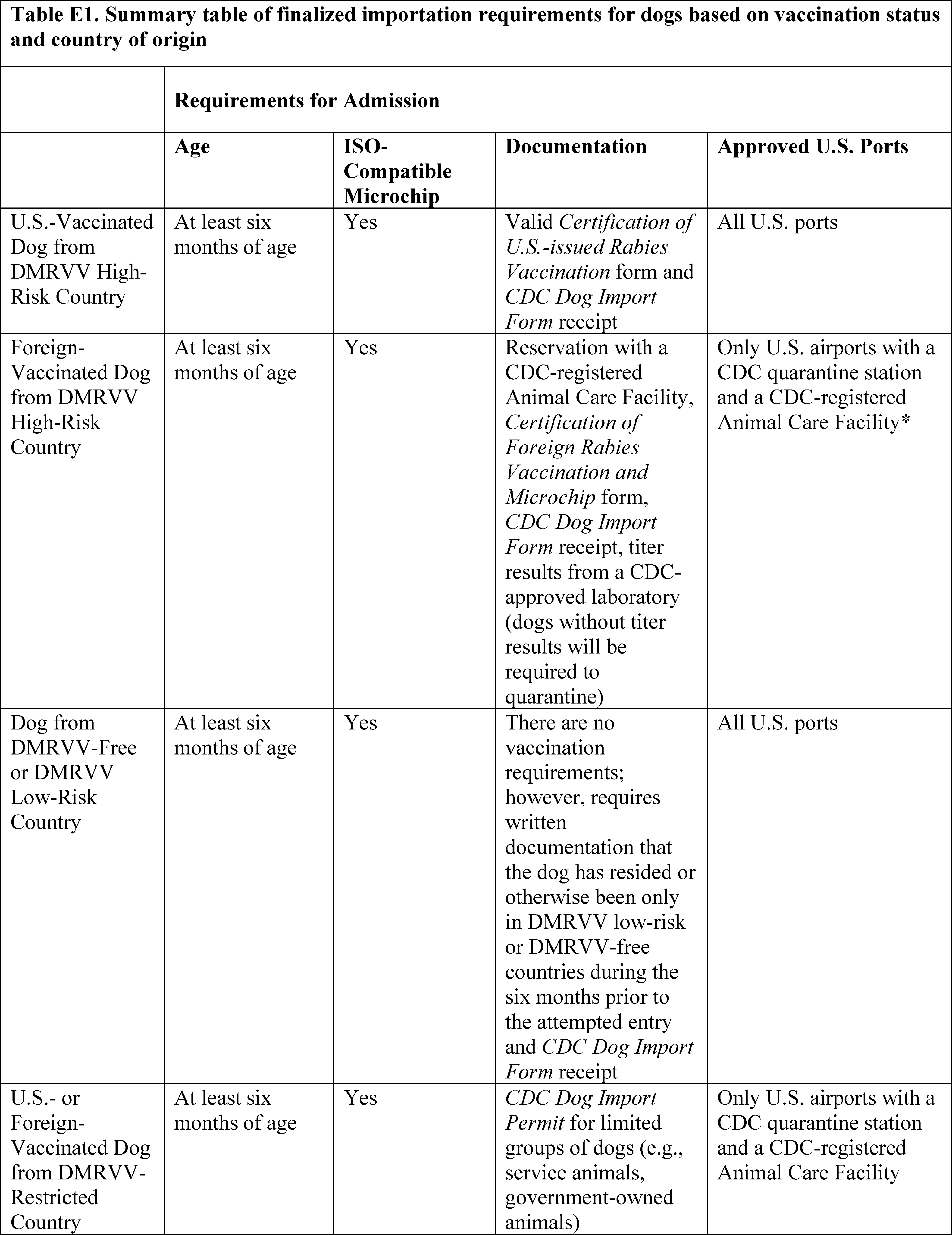

The requirements HHS/CDC is finalizing for dog importation into the United States are summarized below in Table E1. Since HHS/CDC is not substantially changing cat importation requirements, Table E1 does not apply to cats.

Start Printed Page 41731 Start Printed Page 41732The forms HHS/CDC is requiring per this final rule for dog importation into the United States are summarized below in Table E2. Since HHS/CDC is not substantially changing cat importation requirements, Table E2 does not apply to cats.

Start Printed Page 41733The documentation HHS/CDC is requiring be presented at the U.S. port upon arrival for dog importation into the United States is summarized below in Table E3. Because HHS/CDC is not substantially changing cat importation Start Printed Page 41734 requirements, Table E3 does not apply to cats.

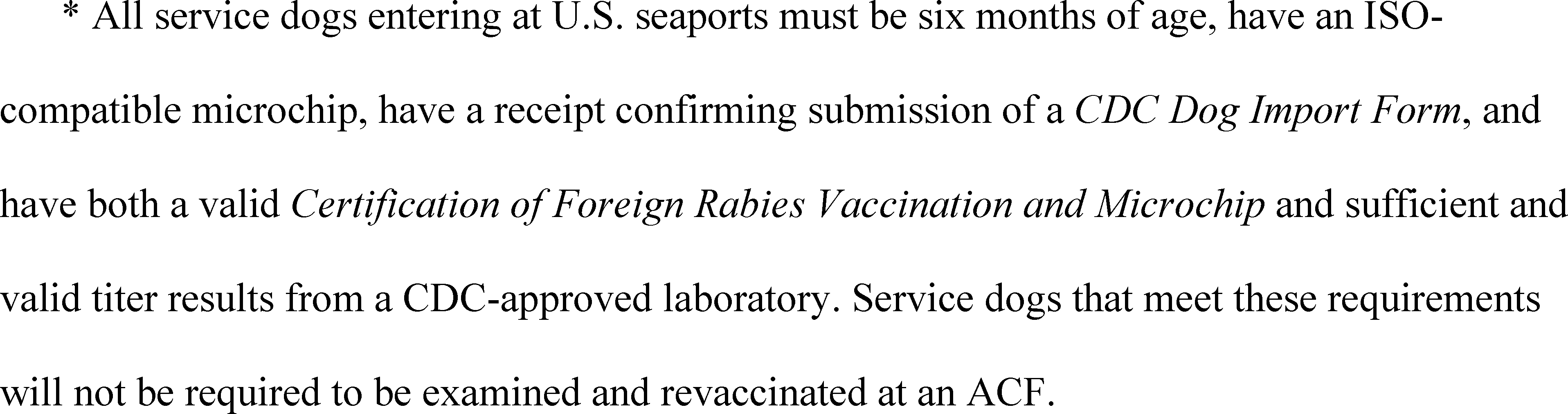

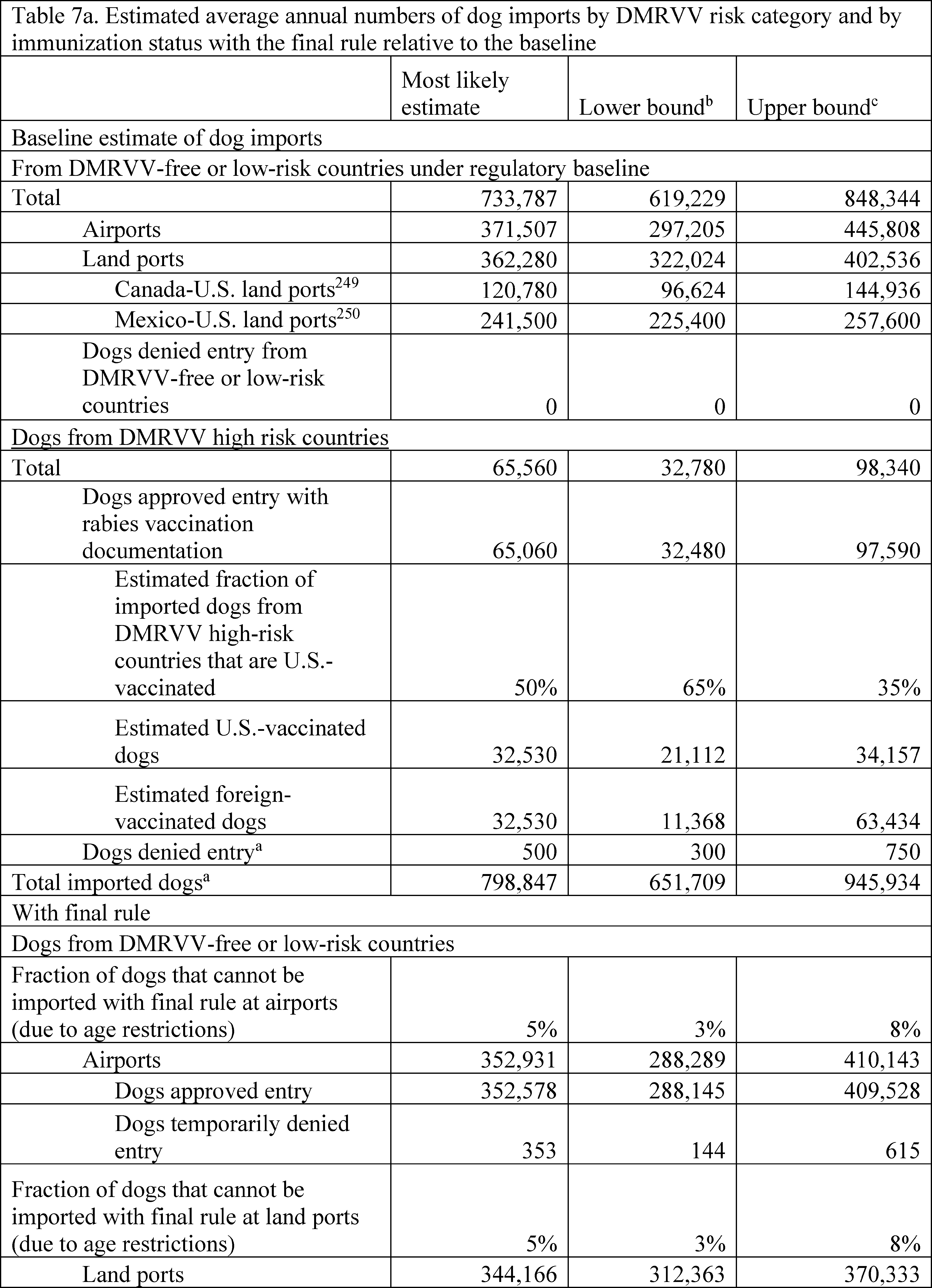

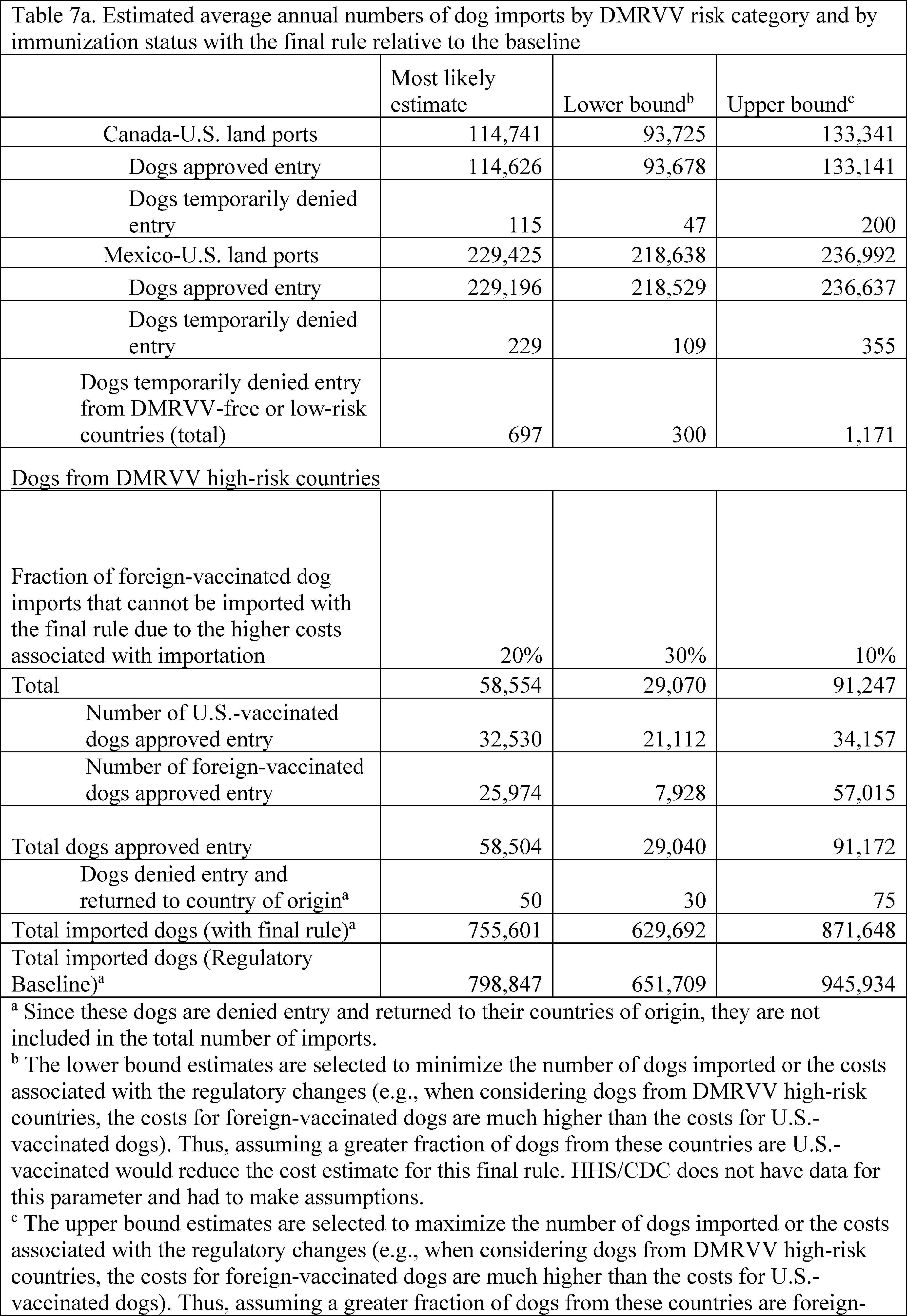

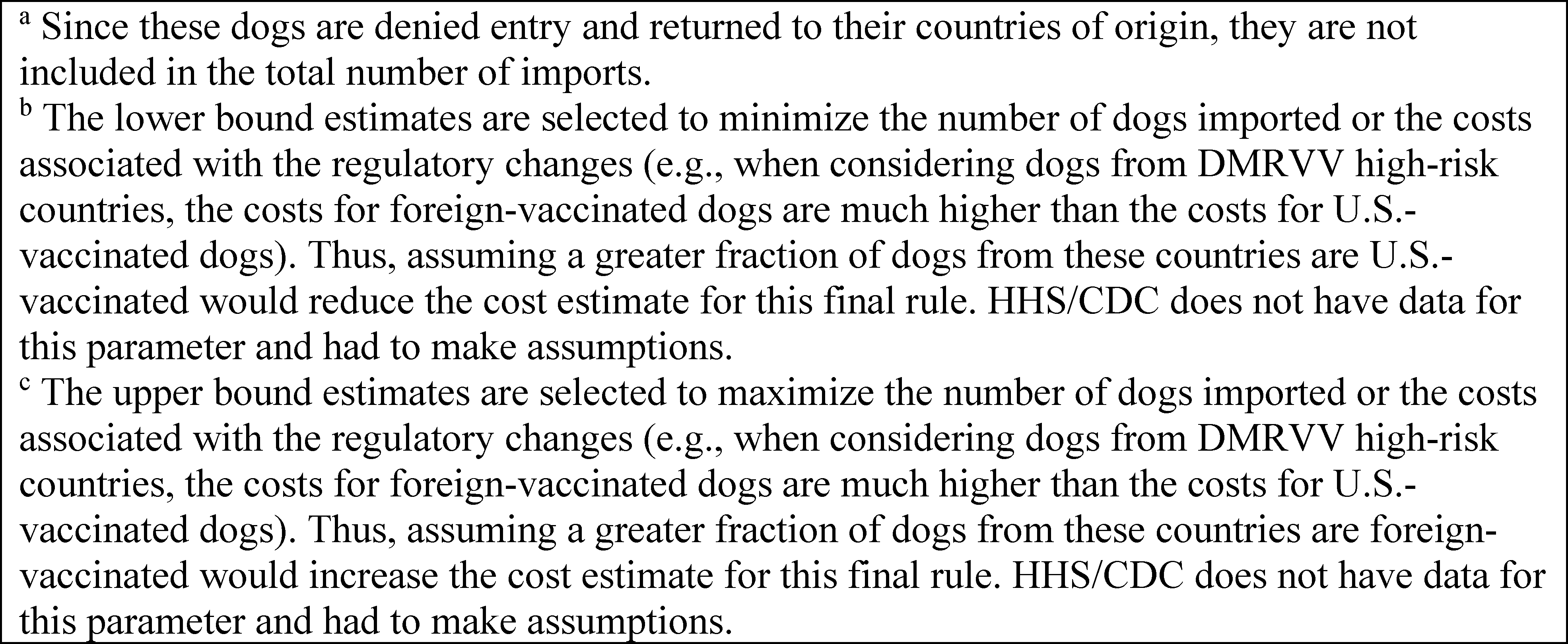

Start Printed Page 41735C. Costs and Benefits

CDC conducted an analysis to estimate the distributions of costs and benefits incurred with the final rule relative to regulatory baseline. The provisions of this final rule are not likely to have an effect on the economy of $200 million or more in any one year, although there is considerable uncertainty around the number of dogs imported at baseline, including the number of dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries.

The requirements of this final rule will address the market inefficiency in which dog importers do not account for the potential detrimental impacts to public health that may result from the importation of ill dogs, especially dogs infected with DMRVV. The worst-case scenario would include the reintroduction of DMRVV into the United States. Federal regulation is necessary to mitigate the risk of importing infected dogs. Federal action allows this risk to be addressed prior to dogs' arrival in the United States and for dogs to be evaluated, revaccinated, and possibly quarantined (if required) in controlled conditions after their arrival in the United States. The primary public health benefit is a reduction in the risk of importing dogs infected with DMRVV. The regulatory changes in this final rule are expected to affect the following categories of interested parties and implementing partners:

- Importers of dogs from countries that are DMRVV-free or are low risk for DMRVV;

- Importers of dogs from countries that are at high risk of DMRVV;

- Airlines and other carriers;

- CBP;

- CDC;

- USDA; and

- State and local public health and animal health departments.

The provisions in the final rule incorporate different requirements for dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries than those imported from DMRVV-free or DMRVV low-risk countries. The annualized and present value estimates of monetized costs and benefits over the 10-year period from 2024 through 2033 using three percent and seven percent discount rates are summarized below. The annualized, monetized costs (2020 USD) of the final rule are estimated to be $59 million (range: $13.1 to $207 million) using a three percent discount rate; the estimated monetized costs using a seven percent discount rate are largely the same.

Most monetized costs are expected to be incurred by importers (87 percent of costs is the most likely estimate). The estimated monetized costs are about three times greater for importers of dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries compared to importers of dogs from DMRVV-free or low-risk countries. The requirements in the final rule estimated to result in the greatest increase in costs for importers of dogs are those associated with the veterinary examination and revaccination against rabies at a CDC-registered ACF for foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries in section 71.51(k), costs for titer testing of foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries, additional costs associated with the CDC Dog Import Form requirement, the minimum age for imported dogs, and the microchip requirements for all imported dogs. Other costs include (1) an expected reduction in the number of dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries, (2) the requirement to arrive at one of six U.S. airports with CDC-registered ACF (required for foreign-vaccinated dogs arriving from DMRVV high-risk countries), and (3) the requirement to obtain a Certification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip form or a Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination form with certification by an official government veterinarian for all dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries. Dogs imported from DMRVV-free or low-risk countries would also require a document certified by an official government veterinarian, but HHS/CDC will allow a greater number of potential documents as specified in 42 CFR 71.51(u).

Airlines are estimated to incur about 7.0 percent of the estimated annualized costs associated with the final rule. Most airline costs would result from ensuring that all transported dogs comply with the new requirements in the final rule, the costs associated with creating bills of lading or a CDC-approved alternative for all imported dogs, and from a small reduction in the number of dogs transported. Airline costs may be passed along to dog importers.

HHS/CDC is estimated to incur about 3.3 percent of the annualized, monetized costs (most likely estimate) associated with the provisions of this final rule. Most CDC costs would be associated with the oversight of animal care facilities, which must be approved by and registered with CDC, and the establishment of a laboratory proficiency testing program to support serologic testing for foreign-vaccinated dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries.

CBP is expected to incur about 3.0 percent of the annualized costs (most likely estimate) associated with the provisions of this final rule. Most CBP costs would result from additional screening time at U.S. ports for dogs from DMRVV-free or low-risk countries.

The annualized monetized benefits of the provisions in the final rule are estimated to be about $1.8 million (range: $0.75 to $3.6 million) using a three percent or seven percent discount rate. Most benefits will accrue to importers (47 percent of the most likely estimates) and to CBP (30 percent of the most likely estimate). Some of the benefits estimated for both importers and CBP will result from reduced time spent on screening dogs from high-risk countries at U.S. ports because fewer dogs will be imported with the requirements included in the final rule. The requirements in the final rule are estimated to reduce the amount of time required to verify admissibility per U.S.-vaccinated dog from DMRVV high-risk country at U.S. ports because rabies vaccination documentation forms will be standardized. The provisions in this final rule are also estimated to reduce the number of dogs arriving ill or dead and the number of dogs denied entry, with benefits estimated for importers, airlines, and CDC. USDA is expected to receive payments commensurate with its cost to provide the Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination form for U.S.-vaccinated dogs traveling internationally.

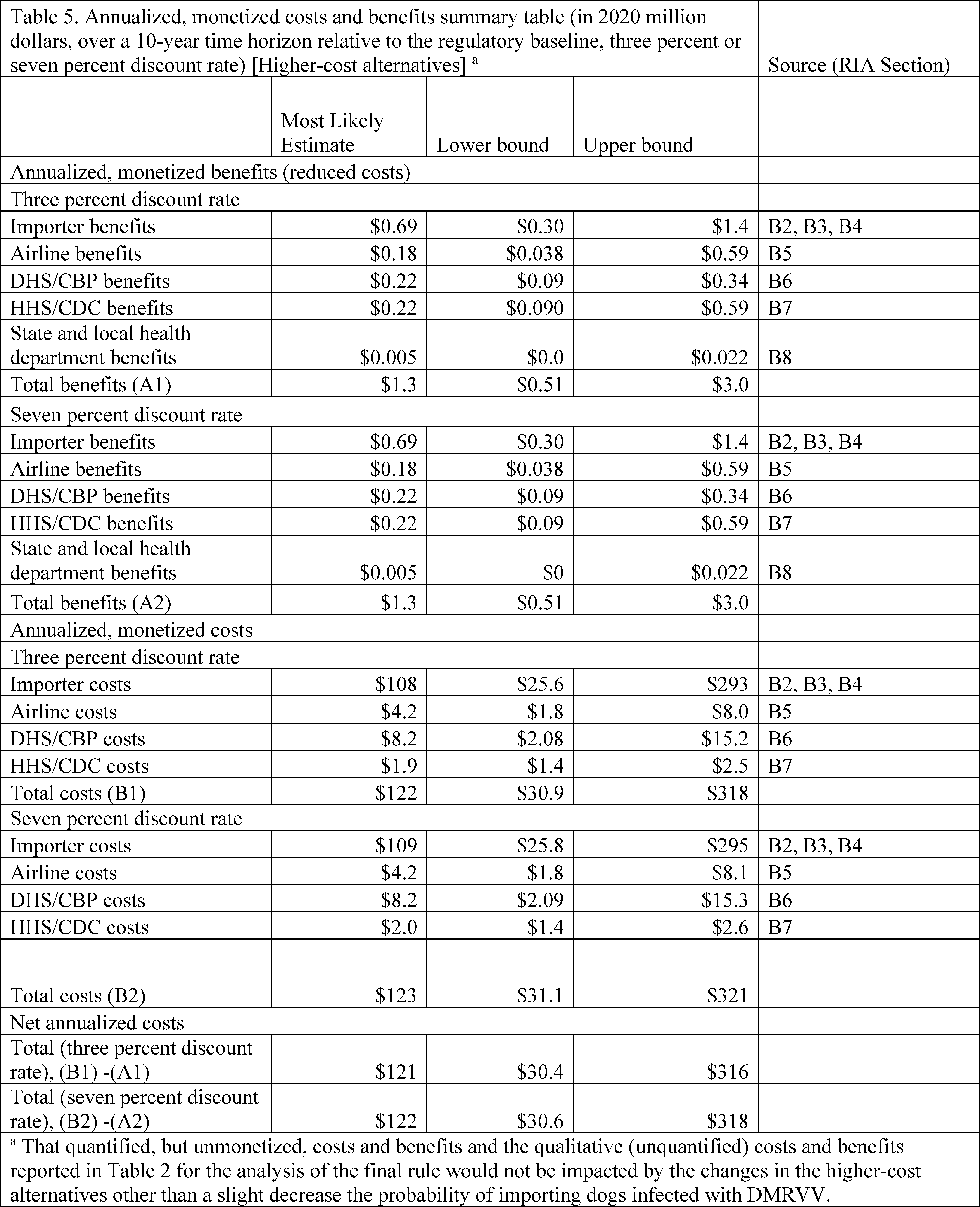

The wide range between the lower-bound and upper-bound cost and benefit estimates demonstrates that there is considerable uncertainty in these results. At present, the number of dogs imported into the United States is neither accurately nor completely tracked by any data system, and the uncertainty in the cost and benefit estimates reflect uncertainty in both the total number of dogs imported and the number of dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries, as well as the cost of the new requirements in the final rule. The net annualized, monetized costs (total cost estimate − total benefit estimate) were estimated to be about $57 million per year (range: $12 to $203 million) using a three percent discount rate. The annualized estimates were relatively unaffected by using a seven percent discount rate.

Because the estimated costs for foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries are much higher than costs for other dog imports, importers may choose to import dogs from DMRVV-free or low-risk countries instead of from DMRVV high-risk countries. In addition, individuals who Start Printed Page 41736 travel from the United States to DMRVV high-risk countries with their pet dogs for long-term visits may take the additional step to have their dogs revaccinated with a three-year rabies vaccine prior to departure, which would allow up to three years for return to the United States with a Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination. These changes should result in lower overall costs than the above estimates for the final rule in which HHS/CDC assumed individuals would be unable to change the countries from which dogs are imported into the United States.

The importation of just one dog infected with DMRVV risks reintroduction of the virus into the United States, which could result in loss of human and animal life and substantial public health response costs. The social cost of the consequences associated with the importation of a single DMRVV-infected dog is estimated to be $270,000 (range: $210,000 to $510,000) for conducting public health investigations and administering rabies PEP to exposed persons. The primary public health benefit of the provisions in the final rule is the reduced risk that a dog with DMRVV will be imported from a DMRVV high-risk country. The above estimate of the cost of importation of a dog with DMRVV does not account for the worst-case outcomes, which include (1) transmission of rabies to a person who dies from the disease, and (2) ongoing transmission to other domestic and wildlife species in the United States. The cost of reintroduction could be especially high if DMRVV spreads to other species of U.S. wildlife. Re-establishment of DMRVV in the United States could result in costly efforts over several years to eliminate the virus again. The costs to contain any reintroduction would depend on the time period before the reintroduction was detected, the wildlife species in which DMRVV was transmitted, and the geographic area over which reintroduction occurred.

An increase in human deaths from DMRVV could occur following the reintroduction of DMRVV to the United States, as the risk of exposure would increase. Human deaths from rabies continue to occur in the United States after exposures to wild animals, and there have been eight deaths among U.S. residents bitten by rabid dogs while traveling abroad in DMRVV high-risk countries since 2009. HHS/CDC uses the value of statistical life (VSL) to support quantifying benefits for interventions that can result in mortality risk reductions. HHS recommends using a central estimate of $11.6 million and a range of $5.5 to $17.7 million (2020 USD). HHS/CDC is unable to estimate the potential magnitude of the mortality risk reduction associated with the final rule. Based on the central VSL, averting five human deaths per year would mean the benefits of the final rule would exceed its costs.

HHS/CDC and other Federal government agencies do not know with precision the number of dogs imported each year or the countries from which the dogs originate. More comprehensive data on where dogs are imported from may benefit public health investigations. Arrival data on animals exposed to a dog with DMRVV on U.S.-bound flights, for example, would expedite follow-up of exposed dogs in the United States. The lack of data received from implementing the current regulation also inhibits the Federal government's ability to target interventions for dogs imported from specific countries. Of note, the COVID-19 pandemic diverted resources from and weakened rabies control programs in some DMRVV high-risk countries, increasing the risk that imported dogs may be infected with DMRVV. The provisions of this final rule will be of particular public health benefit in light of the ongoing resource concerns for global rabies vaccination campaigns in the wake of the pandemic.

These data would also benefit agencies such as USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), which have an interest in regulating dog imports with the intent of reducing the risk of introduction of diseases that may affect U.S. livestock. For example, in 2021, APHIS issued a Federal Order that established additional post-entry requirements on dogs for resale imported from countries with ongoing African swine fever transmission, which poses a significant risk to U.S. pork producers. The potential economic benefits of reducing the risk of the importation of African swine fever could be significant; in fact, a 2019 outbreak in China was estimated to have total economic losses equivalent to 0.78 percent of China's gross domestic product. Thus, some of the requirements in this final rule may mitigate the risks of introduction and transmission of diseases that impact livestock in addition to reducing the risk of importing dogs infected with DMRVV.

The monetized cost estimate has increased considerably relative to the estimates included in the NPRM. The primary reasons for the increase in cost include:

- The fees charged by ACF have increased relative to CDC's preliminary estimates.

- Some U.S. ports require that dogs needing follow-up care at ACF arrive as cargo. This requirement was not anticipated by HHS/CDC and will increase costs for importers of foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries who otherwise would have chosen to transport their dogs as hand-carried or checked baggage. The fee charged for cargo shipments are highly variable.[32 33] The future costs associated with this rule will depend on U.S. port policies that are subject to change. The average cost for the follow-up visit at ACF is estimated to be $900 (range: $500 to $1,300 per dog). The average costs associated with shipping dogs as cargo is estimated to be $2,000 (range: $1,500 to $2,500) [34] compared to an average of $300 (range: $200 to $400) for dogs shipped as hand-carried or checked baggage.[35] Under the regulatory baseline, HHS/CDC assumes 25%, range: 17% to 50% of dogs going to ACF are shipped as cargo. With the final rule, HHS/CDC assumes that 60% of dogs going to ACF, range: 60% to 70% of dogs will be shipped as cargo.

- The cost estimate for foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries to re-route travel destinations to arrive at authorized U.S. ports with ACF was increased.Start Printed Page 41737

- The costs associated with the requirement for proof that a dog has been only in DMRVV low-risk or DMRVV-free countries have increased because HHS/CDC added more examples of the types of proof required. Each type of document requires certification by a USDA or official government veterinarian in the exporting country. Examples include: (a) a valid foreign export certificate from a DMRVV-free or DMRVV low-risk country that has been certified by an official government veterinarian in that country; (b) a USDA export certificate if the certificate is issued to allow the dogs to travel to a DMRVV-free or DMRVV low-risk country, (c) a validCertification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip form if completed in a DMRVV-free or DMRVV low-risk country, or (d) a valid Certification of U.S.-Issued Rabies Vaccination form. These documents are often required for individuals to travel internationally with their pets but are not required for travel to Canada or Mexico. These documents may be used as long as they specify travel to or from the country from which a dog is imported. Individuals who frequently travel to and from Canada and Mexico (or any other country) can obtain a valid Certification of U.S.-Issued Rabies Vaccination form, which will remain valid for multiple trips for up to three years corresponding to the duration of protection for dog rabies vaccines.

- CDC increased the estimated costs associated with shipping blood samples to CDC-approved laboratories for serological testing based on a number of comments from individuals suggesting their shipping costs were higher.

- CDC changed the requirement for importing dogs from DMRVV-free or low-risk countries such that no dogs less than six months may be imported at land borders. This will increase costs for individuals who wish to travel with their young dogs to or from Canada and Mexico.

- CDC increased the estimated costs to airlines by 100% for dogs imported from DMRVV-free or low-risk countries and by 50% for dogs imported from DMRVV high-risk countries to account for a number of comments suggesting that costs to airlines should be higher than the estimates included in the NPRM analysis.

Some of the cost estimates for the final rule have also decreased due to changes made between the NPRM and the final rule. These include:

- The costs to importers of U.S.-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries were reduced because the final rule will not require that such dogs arrive at U.S. ports with CDC quarantine stations.

- The costs for serological testing for foreign-vaccinated dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries were reduced because CDC plans to implement a policy that only one serological test will be required during the lifetime of such dogs as long as they remain current with their rabies vaccinations.

II. Background

a. Legal Authority

The primary legal authority supporting this final rule is section 361 of the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act) (42 U.S.C. 264). Under section 361, the Secretary of HHS (Secretary) may make and enforce such regulations as in the Secretary's judgment are necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases from foreign countries into the United States and from one State or possession into any other State or possession.[36] It also authorizes the Secretary to promulgate and enforce a variety of public health regulations to prevent the spread of communicable diseases, including through inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, destruction of animals or articles found to be sources of dangerous infection to human beings, and other measures. Since at least 1956, Federal quarantine regulations (currently found at 42 CFR 71.51) have controlled the entry of dogs and cats into the United States.[37]

In addition to section 361, other sections of the PHS Act relevant to this final rule are section 362 (42 U.S.C. 265), section 365 (42 U.S.C. 268), section 367 (42 U.S.C. 270), and section 368 (42 U.S.C. 271). Section 362, among other things, authorizes the Secretary to promulgate regulations prohibiting, in whole or in part, the introduction of property from foreign countries or places, for such period of time and as necessary for such purpose, to avert the serious danger of introducing communicable disease into the United States. Section 365 provides that it shall be the duty of customs officers and of Coast Guard officers to aid in the enforcement of quarantine rules and regulations.[38] Through this statutory provision, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) provides critical assistance in enforcing Federal quarantine regulations at U.S. ports. Section 367 (42 U.S.C. 270) also authorizes the application of certain sections of the PHS Act to air navigation and aircraft to such extent and upon such conditions as deemed necessary for safeguarding public health and authorizes the promulgation of regulations.

Section 368 of the PHS Act provides that any person who violates regulations implementing sections 361 or 362 is subject to imprisonment of not more than one year, a fine, or both. Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 3559 and 3571, an individual may face a fine of up to $100,000 for a violation not resulting in death and up to $250,000 for a violation resulting in death. HHS/CDC may refer violators to the U.S. Department of Justice for criminal prosecution. To implement section 368, HHS/CDC would request assistance from other departments and agencies to address violations.

Through this final rule, HHS/CDC is also including new language advising individuals and organizations that it may request that DHS/CBP take additional action pursuant to 19 U.S.C. 1592 and 19 U.S.C. 1595a. Specifically, CDC may request that DHS/CBP issue additional fines, citations, or penalties to importers, brokers, or carriers whenever the CDC Director (Director) has reason to believe that an importer, broker, or carrier has violated any of the provisions of this section or otherwise engaged in conduct contrary to law. HHS/CDC stresses that it does not administer Title 19, and decisions regarding whether to issue such fines, citations, or other penalties would be entirely at the discretion of DHS/CBP and subject to its policies and procedures. Notwithstanding, HHS/CDC Start Printed Page 41738 believes it important to include this language to advise individuals and organizations that it may request that DHS/CBP pursue such actions.

Through this final rule, HHS/CDC is also including new language advising individuals and organizations that it may request that the U.S. Department of Justice investigate, and based on the results of such investigation, prosecute, potential violations of Federal law arising under its dog importation regulations. This includes potential violations of 18 U.S.C. 111 which prohibits persons from forcibly assaulting, resisting, opposing, impeding, intimidating, or interfering with government employees in the conduct of or on account of their official government duties and 18 U.S.C. 1505 which prohibits disrupting agency proceedings. See, e.g., United States v. Schwartz, 924 F.2d 410, 423 (2d Cir. 1991) (holding that a U.S. Customs Service interview of defendants for purposes of determining whether to seize potentially illegal arms was an “agency proceeding” under 18 U.S.C. 1505).

HHS/CDC further clarifies that there is no agency policy of using the “least restrictive means” (as that concept is typically understood and applied in cases involving interests protected by the U.S. Constitution) regarding animal importations under 42 CFR part 71. “The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment imposes procedural constraints on governmental decisions that deprive individuals of liberty or property interests.” Nozzi v. Hous. Auth. of City of Los Angeles, 806 F.3d 1178, 1190 (9th Cir. 2015). However, “[d]ue process protections extend only to deprivations of protected interests.” Shinault v. Hawks, 782 F.3d 1053, 1057 (9th Cir. 2015). Because individuals have no protected property or liberty interest in importing dogs or other animals into the United States, it is HHS/CDC's policy to not employ a constitutional analysis of “least restrictive means” in regard to animal imports under 42 CFR part 71. See Ganadera Ind. V. Block, 727 F.2d 1156, 1160 (D.C. Cir. 1984) (“no constitutionally-protected right to import into the United States”); see also Arjay Assoc. v. Bush, 891 F.2d. 894, 896 (Fed. Cir. 1989) (“It is beyond cavil that no one has a constitutional right to conduct foreign commerce in products excluded by Congress.”).

b. Regulatory Background

On July 10, 2023, HHS/CDC published an NPRM to update 42 CFR 71.50 and 71.51 within its Foreign Quarantine regulations to address the risk to public health from the importation of dogs and cats into the United States. The provisions contained within the NPRM were designed to enhance HHS/CDC's ability to prevent the importation and spread of dog-maintained rabies virus variant (DMRVV) into the United States and interstate by implementing requirements that are used throughout other rabies-free countries and are recommended by animal health organizations ( e.g., World Organisation for Animal Health). CDC evaluates and updates the DMRVV high-risk country list every year and generally posts the updated list on CDC's website [39] by April 1. For this annual country risk assessment, CDC subject matter experts review publicly available data, including data from international organizations (including the World Health Organization (WHO); the WHO Rabies Bulletin—Europe; the Pan-American Health Organization, and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH)); published government reports; scientific publications; and outbreak report alerts such as ProMED,[40] as well as information provided by national and international rabies experts. HHS/CDC will also review the information and re-assess a country's status when presented with additional substantial data to support canine rabies-free status by a foreign country's officials. Lastly, CDC has published the criteria for how it determines a country's classification as a high-risk, low-risk and DMRVV-free country in peer-reviewed journal articles which are publicly available.[41 42] Because of an ongoing risk of reintroduction of DMRVV due to insufficient veterinary controls in countries where DMRVV is still endemic and in parallel with the publication of the NPRM on July 10, 2023, CDC published an extension of the temporary suspension of dogs from DMRVV high-risk countries.[43] Today's final rule has no effect on the temporary suspension, which expires on July 31, 2024. This final rule will go into effect August 1, 2024.

III. Summary of the Final Rule

Changes to 71.50

Section 71.50(b) contains definitions applicable to animal importations under subpart F of 42 CFR part 71. The definitions contained in paragraph (b) are of general scientific applicability and thus would apply to different animal imports, not just dogs and cats. After considering public comment received to the NPRM, HHS/CDC is adding the following definitions to 42 CFR 71.50(b): Authorized veterinarian, cat, dog, histopathology, in-transit shipments, microchip, necropsy, official government veterinarian. CDC is replacing the definition for “in-transit” with the definition “in-transit shipments,” as proposed in the NRPM.

This final rule also adds a new paragraph at 42 CFR 71.50(c) that addresses the legal severability of provisions found in 42 CFR part 71 subpart F—Importations. Because the provisions relating to importations under subpart F are designed to protect the public's health from various communicable disease threats, HHS/CDC intends that these provisions have maximum legal effect. Accordingly, HHS/CDC is adding language to ensure that, if this subpart is held by a reviewing court of law to be invalid or unenforceable by its terms, or as applied to any person or circumstance, the provision be construed so as to continue to give the maximum effect to the provision permitted by law. If a reviewing court should hold that a provision is utterly invalid or unenforceable, then HHS/CDC intends that the provision be severable from Subpart F and not affect the remainder or the application of the provision to persons not similarly situated or to dissimilar circumstances.

Changes to 71.51

Under this final rule, and after considering public comment received to the NPRM, Section 71.51(a) now contains definitions that are specifically applicable to the importation of dogs and cats under this section. HHS/CDC is adding the following definitions: animal, CDC-registered Animal Care Facility, Certification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip, CDC Dog Import Form, Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination, Certification of Dog Arriving from DMRVV-free or Start Printed Page 41739 DMRVV Low-risk Country, conditional release, confinement, DMRVV, DMRVV-free countries, DMRVV high-risk countries, DMRVV low-risk countries, DMRVV-restricted countries, flight parent, importer, SAFE TraQ, serologic testing, USDA-Accredited Veterinarian, and USDA Official Veterinarian. In response to public comment, CDC has modified the definition of importer and added definitions for “flight parent” and “ Certification of Dog Arriving from DMRVV-free or DMRVV Low-risk Country, ” definitions that were not in the NPRM. CDC has also added a definition for CDC Dog Import Permit, and modified and shortened the names of the required rabies vaccination forms. CDC is removing the current definition for Valid rabies vaccination certificate in 42 CFR 71.51 because other rabies vaccination forms will now be required. CDC is also moving the definitions for cat and dog from 71.51(a) to 71.50(a).

In 71.51(b) through 71.51(d), HHS/CDC is finalizing the section as proposed with the exception that U.S.-vaccinated dogs may enter through any U.S. port. CDC has a high degree of confidence in USDA-licensed rabies vaccines administered in the United States; therefore, the risk of a U.S.-vaccinated dog importing rabies when returning to the United States is very low. CDC also has confidence in DMRVV-free countries that have declared themselves to be free of canine rabies using WOAH's self-declared validation process in which their surveillance and vaccination data are available for external review.[44] Additionally, CDC has confidence in DMRVV-free and low-risk countries which demonstrate adequate surveillance capacity and vaccination control measures in accordance with CDC published metrics, but have not pursued a WOAH self-declaration status.[45 46] HHS/CDC is reducing the burden on importers of U.S.-vaccinated dogs by allowing greater flexibility to be admitted through any U.S. port and is finalizing as proposed the ability of importers of cats and dogs from DMRVV-free and low-risk countries to be admitted through any U.S. port.

(b) Authorized U.S. airports for dogs and cats.

Section 71.51(b) is finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC is allowing U.S.-vaccinated dogs to enter through any U.S. airport if the dog is six months of age, microchipped, and accompanied by a valid Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination form and CDC Dog Import Form receipt. Dogs that have been only in DMRVV-free or DRMVV low-risk countries during the last six months and all cats may also enter through any U.S. airport.[47] Foreign-vaccinated dogs that have been in any DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months must enter through a U.S. airport with a CDC quarantine station and an ACF.

(c) Authorized U.S. land ports for dogs and cats.

Section 71.51(c) has been finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC is allowing U.S.-vaccinated dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country in the past six months to enter through any U.S. land port if the dog is six months of age, microchipped, and accompanied by a valid Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination form and CDC Dog Import Form receipt. Dogs that have been only in DMRVV-free or DRMVV low-risk countries during the last six months and all cats may enter through any U.S. land port.

(d) Authorized U.S. seaports for dogs and cats.

Section 71.51(d) has been finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC is allowing U.S.-vaccinated dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country in the past six months to enter through any U.S. seaport if the dog is six months of age, microchipped, and is accompanied by a valid Certification of U.S.-issued Rabies Vaccination form and a CDC Dog Import Form receipt. Dogs that have been only in DMRVV-free or DRMVV low-risk countries during the last six months and all cats may enter through any U.S. seaport.

HHS/CDC is finalizing as proposed the prohibition of entry into the United States through a U.S. seaport for unvaccinated or foreign-vaccinated dogs that have been in a DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months with an exception for dogs meeting the definition of a “service animal” under 14 CFR 382.3. This final rule allows entry if a foreign-vaccinated dog that has been in a DMRVV high-risk country within the last six months accompanies an “individual with a disability” as defined under 14 CFR 382.3. The dog must meet all other CDC requirements for admission of a foreign vaccinated dog from a high-risk country, including that it be microchipped, at least six months of age, have a valid Certification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip form, a valid serologic titer from a CDC-approved laboratory, and a CDC Dog Import Form receipt.

(e) Limitation on U.S. ports for dogs and cats.

Section 71.51(e) is finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC is clarifying that CBP will prescribe the time, place, and manner in which dogs are presented upon arrival at a port of entry, which may include prohibiting dogs from being presented within the Federal Inspection Station. This provision of the final rule also explicitly authorizes the CDC Director to limit the times, U.S. ports, and/or conditions under which dogs or cats may arrive at and be admitted to the United States based on an importer's or carrier's failure to comply with the provisions of this section or as needed to protect the public's health. If the CDC Director determines such a limitation is required, the CDC Director will notify importers or carriers in writing of the specific times, U.S. ports, and/or conditions under which dogs and cats may be permitted to arrive at and be admitted to the United States. This provision is applicable to all U.S. ports, including land, sea, and air.

(f) Age requirement for all dogs.

Section 71.51(f) is finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC removed the exemption for importers to import up to three dogs under six months of age at U.S. land borders if arriving from DMRVV-free or DMRVV low-risk countries. This provision of the final rule requires that all dogs arriving into the United States (regardless of whether from DMRVV-free, DMRVV low-risk, or DMRVV high-risk countries) at air-, land-, and seaports be, at minimum, six months of age. As explained in further detail below, HHS/CDC originally proposed a limited exemption for dogs under six months old primarily to reduce the burden on U.S. travelers who frequently travel across the U.S. and Canada/Mexico borders and choose to travel with young dogs. However, upon further consideration and careful evaluation of the comments received, HHS/CDC has removed the exemption proposed in the NPRM to create a uniform standard for all dogs, ensure U.S.-land borders are not overwhelmed with dog importations, and reduce the risk of importers fraudulently claiming that Start Printed Page 41740 their dog has not been in DMRVV high-risk country.

(g) Microchip requirements for all dogs.

Section 71.51(g) is finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC is clarifying that an imported dog's microchip must have been implanted on or before the date the most recent rabies vaccine was administered. Rabies vaccines administered prior to the implantation of an imported dog's microchip are invalid. HHS/CDC is making this clarification to ensure that the dog receiving the rabies vaccine is properly identified by the microchip. Through this final rule, HHS/CDC is requiring that all dogs have an International Standards Organization (ISO)-compliant microchip prior to arrival in the United States or prior to traveling out of the United States and returning.

(h) CDC Dog Import Form for all dogs.

Section 71.51(h) is finalized as proposed. This provision of the final rule requires that importers submit a CDC Dog Import Form (OMB Control Number 0920-1383; expiration date 04/30/2027) (formerly referred to as the CDC Import Submission Form) via a CDC-approved system for each imported dog. The CDC Dog Import Form must be submitted to CDC prior to a dog's departure from the foreign country. The CDC Dog Import Form receipt must be presented to the airline prior to boarding and to Federal officials upon arrival.

(i) Inspection requirements for admission of dogs and cats.

Section 71.51(i) is finalized as proposed. This final rule requires that dogs and cats may be denied admission if an importer refuses to consent to required inspection, examination, diagnostic testing, or disease surveillance screening.

(j) Examination by a USDA-Accredited Veterinarian and confinement of exposed dogs and cats or those that appear unhealthy.

Section 71.51(j) is finalized as proposed with minor reorganization of the paragraph. This final rule requires that, in the event a dog or cat arrives ill, is denied admission, or is exposed to a sick animal in transit,[48 49] the airline must arrange for confinement in an ACF or CDC-approved veterinary clinic (if an ACF is not available or is unable to adequately care for the ill or injured animal) and transport to the facility in a way that does not expose transportation personnel or the public to communicable diseases. This provision may also be applied to other carriers transporting dogs and cats in the rare circumstances where it is necessary for public health reasons to require that the carrier arrange for examination and confinement. The importer bears the expenses of transportation, confinement, examination, testing, and treatment. The final rule further clarifies an airline's responsibilities in the event an importer abandons a dog or cat. If an importer fails to pay for such expenses, then the animal may be considered abandoned, and the airline will be required to assume financial responsibility.

(k) Veterinary examination, revaccination against rabies, and quarantine at a CDC-registered animal care facility for foreign-vaccinated dogs.

Section 71.51(k) is finalized as proposed with the exception that the paragraph name has been modified to reflect all the required components of the paragraph. However, the requirements within the paragraph have not changed. HHS/CDC is clarifying that suspected or confirmed communicable diseases need only be reported to CDC. Additional notification of Federal, state, and local public health partners will be done by CDC. HHS/CDC now requires that all foreign-vaccinated dogs arriving from DMRVV high-risk countries have a valid Certification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip form and undergo veterinary examination and revaccination against rabies at an ACF upon arrival. The importer is responsible for making a reservation and all arrangements relating to the examination, revaccination, and quarantine (if quarantine is required) of dogs with an ACF prior to the dogs' arrival in the United States.

Airlines must deny boarding to dogs if the importer fails to present a receipt of the completed CDC Dog Import Form (OMB Control Number 0920-1383; expiration date 04/30/2027) and confirmation of a reservation at an ACF. The costs of examination, vaccination, and quarantine (if required) are the responsibility of the importer and not the United States Government. Animals that are abandoned before meeting requirements outlined below become the legal responsibility of the airline.

This final rule further requires that the dogs remain in the custody of an ACF until all of the following requirements are met:

- Veterinary health examination by a USDA-Accredited Veterinarian for signs of disease. Suspected or confirmed communicable or foreign animal diseases would be required to be reported to CDC and may delay release of the animals.

- Confirmation of microchip number.

- Confirmation of age through dental examination by a USDA-Accredited Veterinarian.

- Vaccination against rabies with a USDA-licensed rabies vaccine and administered by a USDA-Accredited Veterinarian.

- Verification of adequate rabies serologic test from a CDC-approved laboratory. To be considered valid, serologic tests must be drawn prior to arrival within an established timeframe and display results within parameters as specified in CDC technical instructions.[50] Dogs that arrive without an adequate rabies serologic test results from a CDC-approved laboratory will be housed at the ACF for a 28-day quarantine following administration of the USDA-licensed rabies vaccine or until an adequate rabies serologic test from a CDC-approved laboratory is confirmed.

(l) Registration or renewal of CDC-registered animal care facilities.

HHS/CDC is finalizing section 71.51(l) as proposed with the exception that CDC may conduct inspections of ACF which will be guided by the USDA Animal Welfare regulation standards (9 CFR parts 1, 2, and 3) and other standards outlined in CDC's Technical Instructions for CDC-registered Animal Care Facilities. Failure to adhere to standard operating procedures (SOP) requirements as outlined in USDA Animal Welfare regulation standards or CDC's Technical Instructions for CDC-registered Animal Care Facilities would constitute grounds for not registering or renewing an ACF's registration.

Per this final rule, HHS/CDC is requiring that an animal care facility register with and receive written approval from CDC, USDA, and CBP to submit their facility application before housing any imported live dog in the United States. The applicant must provide written SOP outlining how CDC's regulatory requirements will be met and the health and safety of animals and staff will be ensured. A copy of all Federal, State, or local registrations, licenses, or permits will also be required to be submitted to CDC. Additionally, HHS/CDC requires the facility to have a USDA intermediate handlers registration (and any other licenses or Start Printed Page 41741 registrations required by USDA) and a FIRMS code issued by CBP.

This section has been finalized as proposed with the clarification that an ACF must be located within 35 miles of a CDC quarantine station. The facility is subject to inspection by CDC at least annually and required to renew their registration every two years. Animal health records, facilities, vehicles, or equipment to be used in receiving, examining, and processing imported animals are also subject to inspection.

(m) Record-keeping requirements at CDC-registered animal care facilities.

Section 71.51(m) is finalized as proposed with the exception that the section references a document other than a bill of lading if the airline has been granted a waiver to the bill of lading requirement under paragraph (dd). The waiver to the bill of lading requirement is discussed more fully in explanation text to section (dd). Per this final rule, HHS/CDC requires that any ACF retain records regarding each imported animal for three years after the distribution or transfer of the animal. Records must be uploaded into CDC's System for Animal Facility Tracking during Quarantine (SAFE TraQ) and completed prior to the animal's release from the facility. HHS/CDC is clarifying that records for necropsy results should be uploaded into SAFE TraQ within 30 days of an animal's death. Each record must include:

- The bill of lading (or other alternative documentation if the airline has been granted a waiver under paragraph (dd)) for each shipment;

- The name, address, phone number, and email address of the importer and owner (if different from the importer);

- The number of animals in each shipment;

- The identity of each animal in each shipment, including name, microchip number, date of birth, sex, breed, and coloring;

- The airline, flight number, date of arrival, and port of each shipment; and

- Veterinary medical records for each animal, including:

Certification of Foreign Rabies Vaccination and Microchip form (OMB Control Number 0920-1383; expiration date 04/30/2027) and rabies serology obtained before arrival in the United States (if applicable);

The USDA-licensed rabies vaccine administered upon arrival;

Veterinary exam records upon arrival and while in quarantine;

Rabies serology performed while in quarantine in the United States (if applicable); and

All diagnostic test, histopathology and necropsy results performed during quarantine (if applicable).

The facility is required to maintain these records electronically and allow CDC to inspect the records.

(n) Worker protection plan and personal protective equipment (PPE).

Section 71.51(n) is finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC is noting that procedures for reporting suspected or confirmed communicable diseases associated with handling animals in facility workers must be reported to CDC within 48 hours. This requirement was included in the NPRM in paragraph (q) and has been moved to paragraph (n) for clarity. Today's final rule requires that an ACF establish and maintain a worker protection plan with standards comparable to those in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration's Recommended Practices for Safety and Health Programs [51] and the National Association of Public Health Veterinarians (NASPHV) Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel.[52] Such a worker protection plan must include rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis consistent with CDC guidance [53] for workers who handle imported animals with signs of illness or in quarantine, and for staff who perform necropsies of imported animals; post-exposure procedures that provide potentially exposed workers with direct and rapid access to a medical consultant; and procedures for documenting the frequency of worker training, including for those working in the quarantine area. As part of the worker protection plan, a facility must also establish, implement, and maintain hazard evaluation and worker communication procedures that include descriptions of the known communicable disease and injury hazards associated with handling animals, the need for PPE when handling animals and training in the proper use of PPE, and procedures for disinfection or safe disposal of garments, supplies, equipment, and waste.

(o) CDC-registered animal care facility standard operating procedures, requirements, and equipment standards for crating, caging, and transporting live animals.

Section 71.51(o) is finalized as proposed and requires that equipment standards for crating, caging, and transporting live animals must be in accordance with USDA Animal Welfare regulation standards (9 CFR parts 1, 2, and 3) and International Air Transport Association standards.[54] Animals must not be removed from crates during transport, and used PPE, bedding, and other potentially contaminated material must be removed from the ground transport vehicle upon arrival at the ACF and disposed of or disinfected in a manner that would destroy potential pathogens of concern.

(p) Health reporting and veterinary service requirements for animals at CDC-registered animal care facilities.

Section 71.51(p) is finalized as proposed with the exception that HHS/CDC may allow veterinarians to confirm the age of a dog using alternative methods approved by CDC, such as ocular lens examination or radiographs. Additionally, HHS/CDC is clarifying that if an animal is suspected of having a communicable disease, it must be immediately isolated and CDC-registered ACF must implement infection prevention and control measures in accordance with industry standards and CDC technical instructions. HHS/CDC is clarifying that suspected or confirmed communicable diseases need only be reported to CDC and not to other public health entities. Additional notification of Federal, State, and local public health partners will be done by CDC. HHS/CDC also notes the paragraph name has been modified to reflect all the required components of the paragraph. However, the requirements within the paragraph have not changed. Today's final rule establishes health reporting requirements for all dogs evaluated at an ACF. Under this provision, a facility must provide the following services for each dog from a DMRVV high-risk country with a foreign-issued rabies vaccine upon arrival and ensure each animal meets CDC, USDA, and State and local entry requirements prior to release from the facility:

- Veterinary examination by a USDA-Accredited Veterinarian within one business day of arrival;

- Verification of microchip and confirmation that the microchip number matches the animal's health records;

- Verification of animal's age via a dental examination (or other CDC-approved method);

- Vaccination against rabies using a USDA-licensed vaccine; andStart Printed Page 41742

- Confirmation of an adequate serologic test from a CDC-approved laboratory OR completion of a 28-day quarantine after administration of the USDA-licensed rabies vaccine.

This provision also requires that the facility notify CDC within 24 hours of the occurrence of any morbidity or mortality of animals in the facility. Any animal that dies during transport or while in quarantine at a ACF is required to undergo a necropsy and diagnostic testing to determine the cause of death. An animal that arrives ill or becomes ill while at the ACF must be examined by a USDA-Accredited Veterinarian immediately and must undergo diagnostic testing to determine the cause of illness prior to release from the facility. Suspected or confirmed communicable diseases in animals must be reported to CDC within 24 hours of identification.