2016-23710. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Finding on a Petition To List the Western Glacier Stonefly as an Endangered or Threatened Species; Proposed Threatened Species Status for Meltwater Lednian Stonefly and Western ...

-

Start Preamble

AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Proposed rule; 12-month petition finding and status review.

SUMMARY:

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), announce a 12-month finding for the western glacier stonefly (Zapada glacier). After a review of the best available scientific and commercial information, we find that listing the western glacier stonefly is warranted. We are also announcing the proposed listing rule for the candidate species meltwater lednian stonefly (Lednia tumana). Therefore, we are proposing to list both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly, two insect species from Glacier National Park and northwestern Montana, as threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (Act). If we finalize this rule as proposed, it would extend the Act's protections to these species. The effect of this regulation will be to add these species to the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. The Service seeks data and comments from the public on this proposed listing rule.

DATES:

We will accept comments received or postmarked on or before December 5, 2016. Comments submitted electronically using the Federal eRulemaking Portal (see ADDRESSES below) must be received by 11:59 p.m. Eastern Time on the closing date. We must receive requests for public hearings, in writing, at the address shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT by November 18, 2016.

ADDRESSES:

You may submit comments by one of the following methods:Start Printed Page 68380

(1) Electronically: Go to the Federal eRulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov. In the Search box, enter FWS-R6-ES-2016-0086, which is the docket number for this rulemaking. Then, in the Search panel on the left side of the screen, under the Document Type heading, click on the Proposed Rules link to locate this document. You may submit a comment by clicking on “Comment Now!”

(2) By hard copy: Submit by U.S. mail or hand-delivery to: Public Comments Processing, Attn: FWS-R6-ES-2016-0086; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, MS: BPHC, 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA 22041-3803.

We request that you send comments only by the methods described above. We will post all comments on http://www.regulations.gov. This generally means that we will post any personal information you provide us (see Public Comments below for more information).

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Jodi Bush, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Montana Ecological Services Field Office, 585 Shepard Way, Helena, MT 59601, by telephone 406-449-5225 or by facsimile 406-449-5339. Persons who use a telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD) may call the Federal Information Relay Service (FIRS) at 800-877-8339.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. Under the Act, if a species is determined to be an endangered or threatened species throughout all or a significant portion of its range, we are required to promptly publish a proposal in the Federal Register and make a determination on our proposal within 1 year. Critical habitat shall be designated, to the maximum extent prudent and determinable, for any species determined to be an endangered or threatened species under the Act. Listing a species as an endangered or threatened species and designations and revisions of critical habitat can only be completed by issuing a rule. In the near future, we intend to publish a proposal to designate critical habitat for meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly. Designation of critical habitat is prudent, but not determinable at this time.

This document proposes the listing of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly as threatened species. The meltwater lednian stonefly is a candidate species for which we have on file sufficient information on biological vulnerability and threats to support preparation of a listing proposal, but for which development of a listing regulation has been precluded by other higher priority listing activities. We were petitioned to list the western glacier stonefly and published a substantial 90-day finding in 2011. We assessed all information regarding status of and threats to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly that was available through August 11, 2016. However, we received additional information on western glacier stonefly on August 12, 2016, indicating a larger range than previously known. Because we received this new information late in the status review process, we were unable to fully incorporate and analyze the new information in this document in time to meet the settlement agreement deadline of submitting a 12-month finding for western glacier stonefly to the Federal Register by September 30, 2016. As such, we plan to reopen the comment period on this proposed listing rule in the near future when we have been able to fully incorporate and analyze the new information and allow the public to comment on the new information and our analysis of it at that time. The current document consists of the 12-month finding for the western glacier stonefly, for which we find listing is warranted, and proposed rules to list both stonefly species.

The basis for our action. Under the Act, we can determine that a species is an endangered or threatened species based on any of five factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) Disease or predation; (D) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. We have determined that habitat fragmentation and degradation resulting from climate change are current and future threats to the viability of both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly. Drought is expected to be a threat to both stonefly species in the foreseeable future.

We will seek peer review. We will seek comments from appropriate and independent specialists to ensure that our determination is based on scientifically sound data, assumptions, and analyses. We will invite these peer reviewers to comment on our listing proposal. Because we will consider all comments and information received during the comment period, our final determinations may differ from this proposal.

Information Requested

Public Comments

We intend that any final action resulting from this proposed rule will be based on the best scientific and commercial data available and be as accurate and as effective as possible. Therefore, we request comments or information from the public, other concerned governmental agencies, Native American tribes, the scientific community, industry, or any other interested parties concerning this proposed rule. Because we will consider all comments and information received during the comment period, our final determinations may differ from this proposal. We particularly seek comments concerning:

(1) The meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly biology, range, and population trends, including:

(a) Biological or ecological requirements of the species, including habitat requirements for feeding, breeding, and sheltering;

(b) Genetics and taxonomy;

(c) Historical and current range including distribution patterns;

(d) Historical and current population levels, and current and projected trends; and

(e) Past and ongoing conservation measures for the species, their habitat, or both.

(2) Factors that may affect the continued existence of the species, which may include habitat modification or destruction, overutilization, disease, predation, the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms, or other natural or manmade factors.

(3) Biological, commercial trade, or other relevant data concerning any threats (or lack thereof) to these species and existing regulations that may be addressing those threats.

(4) Additional information concerning the historical and current status, range, distribution, and population size of these species, including the locations of any additional populations.

As referenced above in the Executive Summary, we will be reopening the comment period for this proposed listing rule in the near future once we incorporate and analyze the new information we recently obtained on western glacier stonefly, which is further described under Distribution and Abundance below. During the reopening of the comment period, we will seek comments concerning the new information describing the expanded range and additional populations of western glacier stonefly.

Please include sufficient information with your submission (such as scientific Start Printed Page 68381journal articles or other publications) to allow us to verify any scientific or commercial information you include.

Please note that submissions merely stating support for or opposition to the action under consideration without providing supporting information, although noted, will not be considered in making a determination, as section 4(b)(1)(A) of the Act directs that determinations as to whether any species is a threatened or endangered species must be made “solely on the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available.”

You may submit your comments and materials concerning this proposed rule by one of the methods listed in ADDRESSES. We request that you send comments only by the methods described in ADDRESSES.

If you submit information via http://www.regulations.gov,, your entire submission—including any personal identifying information—will be posted on the Web site. If your submission is made via a hardcopy that includes personal identifying information, you may request at the top of your document that we withhold this information from public review. However, we cannot guarantee that we will be able to do so. We will post all hardcopy submissions on http://www.regulations.gov.

Comments and materials we receive, as well as supporting documentation we used in preparing this proposed rule, will be available for public inspection on http://www.regulations.gov,, or by appointment, during normal business hours, at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Montana Ecological Services Field Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT).

Public Hearing

Section 4(b)(5) of the Act provides for one or more public hearings on this proposal, if requested. Requests must be received within 45 days after the date of publication of this proposed rule in the Federal Register. Such requests must be sent to the address shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT. We will schedule public hearings on this proposal, if any are requested, and announce the dates, times, and places of those hearings, as well as how to obtain reasonable accommodations, in the Federal Register and local newspapers at least 15 days before the hearing.

Peer Review

In accordance with our joint policy on peer review published in the Federal Register on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34270), we are seeking the expert opinions of three appropriate and independent specialists regarding this proposed rule. The purpose of peer review is to ensure that our listing determinations are based on scientifically sound data, assumptions, and analyses. The peer reviewers have expertise in stonefly biology, habitat, and life history. We invite comment from the peer reviewers during the public comment periods.

Previous Federal Action

Meltwater Lednian Stonefly

On July 30, 2007, we received a petition from Forest Guardians (now WildEarth Guardians) requesting that the Service: (1) Consider all full species in our Mountain Prairie Region ranked by the organization NatureServe as G1 or G1G2 (which includes the meltwater lednian stonefly), except those that are currently listed, proposed for listing, or candidates for listing; and (2) list each species as either endangered or threatened (Forest Guardians 2007, pp. 1-37). We replied to the petition on August 24, 2007, and stated that, based on preliminary review, we found no compelling evidence to support an emergency listing for any of the species covered by the petition, and that we planned work on the petition in Fiscal Year (FY) 2008.

On March 19, 2008, WildEarth Guardians filed a complaint (1:08-CV-472-CKK) indicating that the Service failed to comply with its mandatory duty to make a preliminary 90-day finding on their two multiple species petitions in two of the Service's administrative regions—one for the Mountain-Prairie Region and one for the Southwest Region (WildEarth Guardians v. Kempthorne 2008, case 1:08-CV-472-CKK). We subsequently published two initial 90-day findings on January 6, 2009 (74 FR 419), and February 5, 2009 (74 FR 6122), identifying species for which we were then making negative 90-day findings, and species for which we were still working on a determination. On March 13, 2009, the Service and WildEarth Guardians filed a stipulated settlement in the District of Columbia Court, agreeing that the Service would submit to the Federal Register a finding as to whether WildEarth Guardians' petition presents substantial information indicating that the petitioned action may be warranted for 38 Mountain-Prairie Region species by August 9, 2009 (WildEarth Guardians v. Salazar 2009, case 1:08-CV-472-CKK).

On August 18, 2009, we published a partial 90-day finding for the 38 Mountain-Prairie Region species, and found that the petition presented substantial information to indicate that listing of the meltwater lednian stonefly may be warranted based on threats from habitat loss and degradation due to climate change, and specifically the melting of glaciers associated with the species' habitat; and went on to request further information pertaining to the species (74 FR 41649, 41659-41660).

On April 5, 2011, we published a 12-month finding (76 FR 18684) for the meltwater lednian stonefly indicating that listing was warranted, but precluded by higher priority listing actions. At that time, the meltwater lednian stonefly was added to our list of candidate species with a listing priority number (LPN) of 4. In the 2011 candidate notice of review (76 FR 66370, October 24, 2011; p. 66376), we announced a revised LPN of 5 for the species due to research that showed the meltwater lednian stonefly was no longer considered to be a monotypic genus. In each successive year since then we reaffirmed our 2011 finding of warranted but precluded and maintained a listing priority number of 5 for the species.

Western Glacier Stonefly

On January 10, 2011, we received a petition to list the western glacier stonefly from the Xerces Society and Center for Biological Diversity. We replied to the petition on August 3, 2011, indicating that emergency listing was not warranted. On December 19, 2011, we published a 90-day finding (76 FR 78601) for the western glacier stonefly indicating there was substantial scientific information indicating that listing of the species may be warranted. On April 15, 2015, the Center for Biological Diversity filed an amended complaint (1:15-CV-00229-EGS) seeking 12-month findings for several species, including the western glacier stonefly. On September 15, 2015, the Service and the Center for Biological Diversity filed a stipulated settlement in the District of Columbia Court, agreeing that the Service would submit to the Federal Register a 12-month finding for the western glacier stonefly by September 30, 2016 (Center for Biological Diversity v. Jewell 2009, case 1:15-CV-00229-EGS). This document contains the status review and 12-month finding for the species.

Because both stonefly species occupy similar habitat in the same geographic region of northwestern Montana and are faced with similar threats, we have batched them into one status review and subsequent proposed rule for efficiency. Therefore, this document constitutes both the 12-month finding and proposed listing rule for the western glacier stonefly, and the proposed listing rule for the meltwater lednian stonefly.Start Printed Page 68382

Background

Taxonomy and Species Description

The meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies are small insects that begin life as eggs, hatch into aquatic nymphs, and later mature into winged adults, surviving briefly on land before reproducing and dying. The nymph, or aquatic juvenile stage, of the meltwater lednian stonefly is dark red-brown on its dorsal surface and pink on the ventral surface, with light grey-green legs (Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658). Mature nymphs can range in size from 4.5 to 6.5 millimeters (mm) (0.18 to 0.26 in.; Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 655). Nymphs mature into the adult terrestrial phase that has wings and body sizes ranging from 4 to 6 mm (0.16 to 0.24 in.; Baumann 1975, p. 79). Western glacier stonefly nymphs are similar in color and size to meltwater stonefly nymphs. Western glacier stonefly adults are generally brown in color with yellowish brown legs and possess two sets of translucent wings (Baumann and Gaufin 1971, p. 275). Adults range from 6.5 to 10.0 millimeters (mm) (0.26 to 0.39 inches (in)) in body length (Baumann and Gaufin 1971, p. 275). Western glacier stonefly nymphs cannot be distinguished from other Zapada nymphs using gross morphological characteristics. Thus, DNA barcoding (in which DNA sequences of unidentified nymphs are compared with those of positively identified adults) must be used to positively identify western glacier stonefly nymphs.

The meltwater lednian stonefly was originally described by Ricker in 1952 (Baumann 1975, p. 18) from the Many Glacier area of Glacier National Park (GNP), Montana (Baumann 1982, pers. comm.). The meltwater lednian stonefly belongs to the phylum Arthropoda, class Insecta, order Plecoptera (stoneflies), family Nemouridae, and subfamily Nemourinae. Until recently, the meltwater lednian stonefly was believed to be the only species in the genus Lednia (Baumann 1975, p. 19; Stewart and Harper 1996, p. 263; Stark et al. 2009, entire; 76 FR 18688). However, three additional species (L. borealis-Cascade Range, Washington; L. sierra-Sierra Madre Range, California; and L. tetonica-Wind River Range, Wyoming) have been described in the genus Lednia since 2010 (Baumann and Kondratieff 2010, entire; Baumann and Call 2012, entire). Thus, the Service no longer considers the genus Lednia to be monotypic. The meltwater lednian stonefly is recognized as a valid species by the scientific community (e.g., Baumann 1975, p. 18; Baumann et al. 1977, pp. 7, 34; Newell et al. 2008, p. 181; Stark et al. 2009, entire), and no information is available that disputes this finding. Consequently, we conclude that the meltwater lednian stonefly (Lednia tumana) is a valid species and, therefore, a listable entity under section 3(16) of the Act.

The western glacier stonefly was first described in 1971 from adult specimens collected from five locations in GNP, Montana (Baumann and Gaufin 1971, p. 277). The western glacier stonefly is in the same family as the meltwater lednian stonefly (i.e., family Nemouridae; Baumann 1975, pp. 1, 31; Service 2011, p. 18688), but a different genus (Zapada). Members of the Zapada genus are the most common of the Nemouridae family (Baumann 1975, p. 31). The western glacier stonefly is recognized as a valid species by the scientific community (Baumann 1975, p. 30; Stark 1996, entire; Stark et al. 2009, p. 8), and no information is available that disputes this finding. Consequently, we conclude that the western glacier stonefly is a valid species and, therefore, a listable entity under section 3(16) of the Act.

Distribution and Abundance

Meltwater Lednian Stonefly

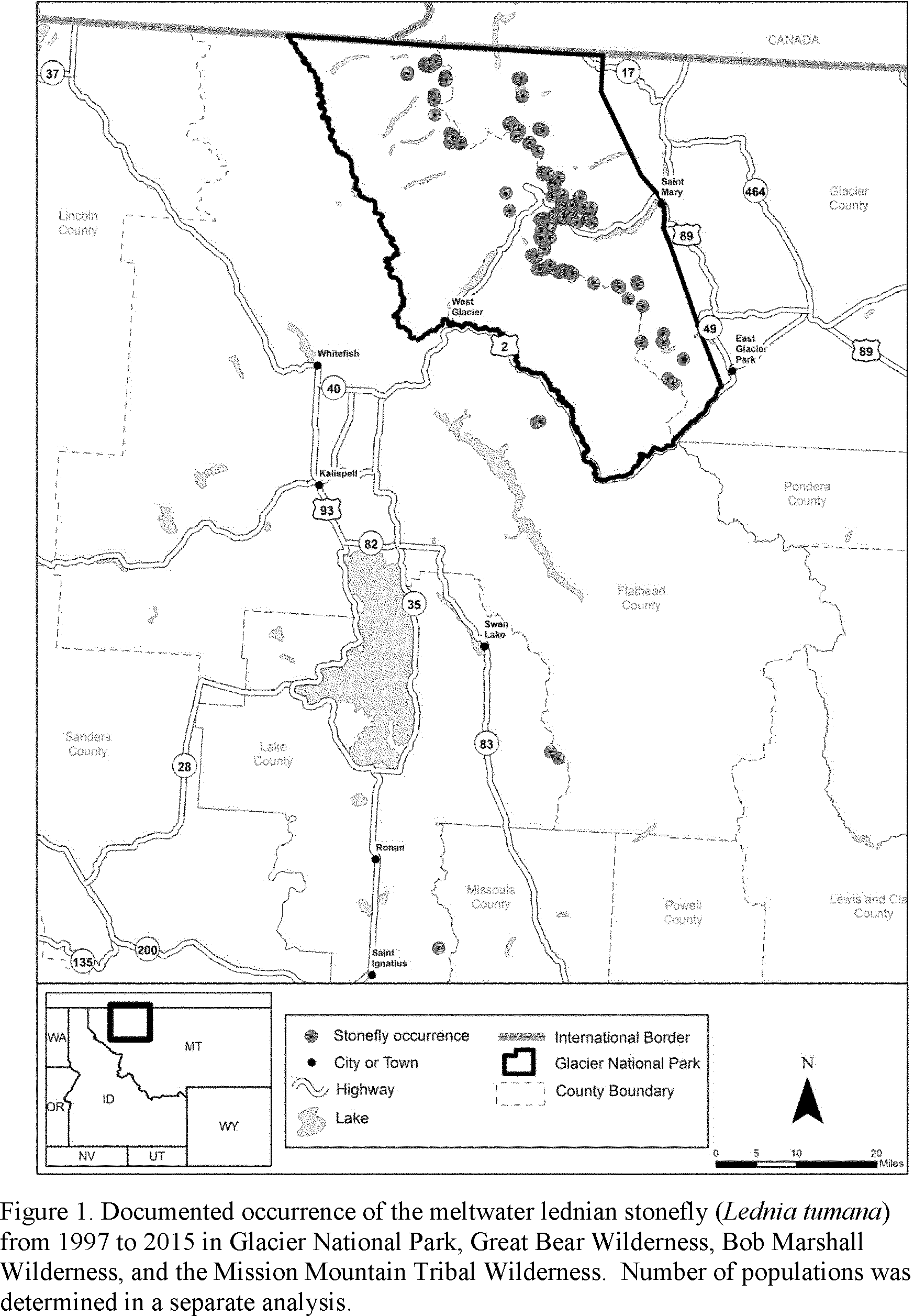

Fifty-eight populations of meltwater lednian stoneflies are known to occur; these are located primarily within GNP, with a few populations recorded south of GNP on National Forest and tribal lands (Figure 1; Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Meltwater lednian stonefly occupy relatively short reaches of streams [mean = 565 meters (m) (1,854 feet; ft); range = 1-2,355 m (3-7,726 ft)] below meltwater sources (for description, see Habitat section below; Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Meltwater lednian stoneflies can attain moderate to high densities [(350-5,800 per square m) (32-537 per square ft)] (e.g., Logan Creek: Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658; NPS 2009, entire; Muhlfeld et al. 2011, p. 342; Giersch 2016, pers. comm.). Given this range of densities and a coarse assessment of available habitat, the abundance of meltwater lednian stonefly is estimated to be in the millions of individuals, however, no population trend information is available for the meltwater lednian stonefly.

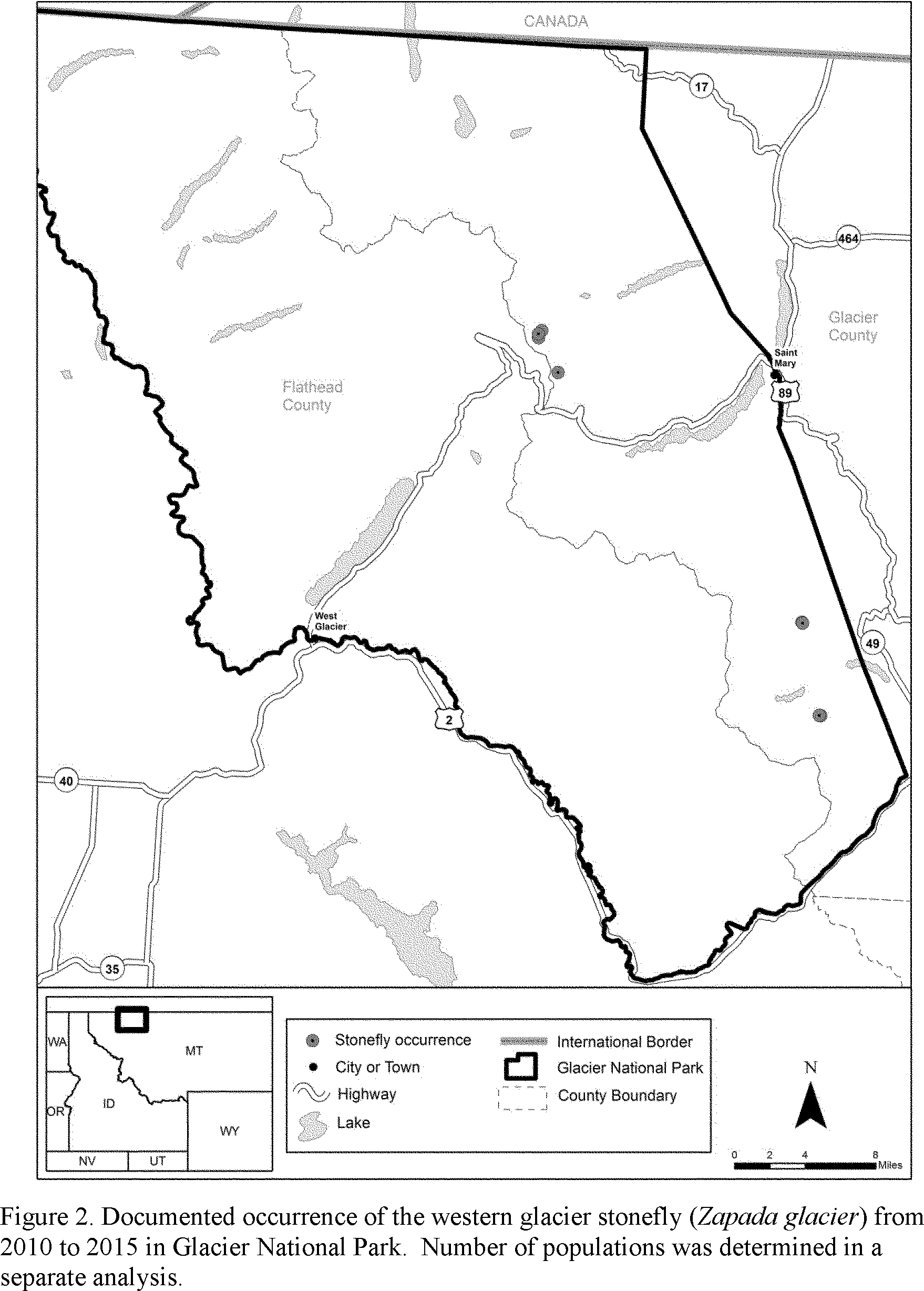

Start Printed Page 68383Western Glacier Stonefly

Four populations of the western glacier stonefly are known to occur, all within the boundaries of GNP (Figure 2; Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Similar to the meltwater lednian stonefly, western glacier stoneflies are found on relatively short reaches of strems in close proximity to meltwater sources [means = 508 m (1,667 ft.); range = 15-1407 m (49-4,616 ft.)] (Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Western glafier stoneflies can attain moderate densities [(400-2,300 per square m) (37-213 per square ft)] (Giersch 2016, pers. comm.). Given this Start Printed Page 68384range of densities and a coarse assessment of available habitat, the abundance of the western glacier stonefly is estimated to be in the tens of thousands of individuals, less numerous than the meltwater lednian stonefly.

Western glacier sotneflies have decreased in distribution among and within 6 streams where the species occurred in the 1960s and 1970s in GNP (Giersch et al. 2015, p. 58). Of the four known populations of the western glacier stonelfy, three were first documented relatively recently in GNP (Giersch et al. 2015, p.59; giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). In August 2016, we received new information indicating that the distribution of western glacier stonefly extends outside of GNP, including one population in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness in southwestern Montana and three populations in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. This distribution represents a large range expansion (500 km southward) for western glacier stonefly compared to the range previously known for the species. However, because we received this information too late in the status review process to be able to incorporate it in time to meet the settlement agreement deadline of September 30, 2016, we have not yet fully evaluated this information, or incorporated it into our analysis or this proposed rule. We intend to reopen the comment period on the proposed listing rule when this information has been fully incorporated and analyzed.

Start Printed Page 68385The northern distributional limits of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly are not known. Potential habitat for meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, similar to what both species are currently occupying, exists in the area of Banff and Jasper National Parks, Alberta, Canada. Aquatic invertebrate surveys have been conducted in this area, and no specimens of either species were found, although it is likely that sampling did not occur close enough to glaciers or icefields to detect either meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly, if indeed they were present (Hirose 2016, pers. comm.). Sampling in this area for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies is planned for the future and would help fill in an Start Printed Page 68386important data gap with regard to northern distributional limits of both species.

Habitat

Meltwater Lednian Stonefly

The meltwater lednian stonefly is found in high-elevation, fishless, alpine streams (Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658; MNHP 2010a) originating from meltwater sources, including glaciers and small icefields, permanent and seasonal snowpack, alpine springs, and glacial lake outlets (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107; Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Meltwater lednian stonefly are known from alpine streams where mean and maximum water temperatures do not exceed 10 °C (50 °F) and 18 °C (64 °F), respectively (Muhlfeld et al. 2011, p. 342), although the species can withstand higher water temperatures (~20 °C; 68 °F) for short periods of time (Treanor et al. 2013, p. 602). In general, the alpine streams inhabited by the meltwater lednian stonefly are presumed to have very low nutrient concentrations (low nitrogen and phosphorus), reflecting the nutrient content of the glacial or snowmelt source (Hauer et al. 2007, pp. 107-108). During the daytime, meltwater lednian stonefly nymphs prefer to occupy the underside of rocks or larger pieces of bark or wood (Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658; Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress).

Western Glacier Stonefly

Western glacier stoneflies are found in high-elevation, fishless, alpine streams closely linked to the same meltwater sources as the meltwater lednian stonefly (Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). The specific thermal tolerances of the western glacier stonefly are not known. However, all recent collections of the western glacier stonefly in GNP have occurred in habitats with daily maximum water temperatures less than 6.3 °C (43 °F) (Giersch et al. 2015, p. 61). Further, abundance patterns for other species in the Zapada genus in GNP indicate preferences for the coolest environmental temperatures, such as those found at high elevation in proximity to headwater sources (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 110). Daytime microhabitat preferences of the western glacier stonefly appear similar to those for the meltwater lednian stonefly (Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress).

Biology

Little information is available on the biology of the meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies. However, we assume that both species are likely to be similar to other closely related stoneflies in the Nemouridae family in terms of habitat needs and life-history traits. In general, Nemouridae stoneflies are primarily associated with clean, cool or cold, flowing waters (Baumann 1979, pp. 242-243; Stewart and Harper 1996, p. 217). Eggs and nymphs of Nemouridae stoneflies are aquatic (Stewart and Harper 1996, p. 217), and nymphs rely on perennial water sources to breathe through gills, similar to fish. Nemouridae nymphs are typically herbivores or detritivores, and their feeding mode is generally that of a shredder or collector-gatherer (Baumann 1975, p. 1; Stewart and Harper 1996, pp. 218, 262). Typically, Nemouridae stoneflies complete their life cycles within a single year (univoltine) or in 2 to 3 years (semivoltine) (Stewart and Harper 1996, pp. 217-218).

Mature stonefly nymphs emerge from the water and complete their development in the terrestrial environment as short-lived adults on and around streamside vegetation or other structures (Hynes 1976, pp. 135-136; Stewart and Harper 1996, p. 217). It is unknown if adult stoneflies select for particular features in the terrestrial environment. Timing of stonefly emergence is influenced by temperature and amount of daylight (Nebeker 1971 cited in Hynes 1976, p. 137). Adult meltwater lednian stoneflies are believed to emerge and breed in August and September (Baumann and Stewart 1980, p. 658; Giersch 2010b, pers. comm.; MNHP 2010a). Adult western glacier stoneflies have been collected from land in early July through mid-August (Baumann and Gaufin 1971, p. 277), almost immediately after snow has melted and exposed streams.

Nemouridae stoneflies disperse longitudinally (up or down stream) or laterally to the stream bank from their benthic (nymphal) source (Hynes 1976, p. 138; Griffith et al. 1998, p. 195; Petersen et al. 2004, pp. 944-945). Generally, adult stoneflies stay close to the channel of their source stream (Petersen et al. 2004, p. 946), and lateral movement into neighboring uplands is confined to less than 80 meters (262 feet) from the stream (Griffith et al. 1998, p. 197). Thus, Nemouridae stoneflies, and likely meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, have limited dispersal capabilities.

Adult male and female stoneflies are mutually attracted by a drumming sound produced by tapping their abdomens on a substrate (Hynes 1976, p. 140). After mating, females deposit a mass of fertilized eggs in water where they are widely dispersed or attached to substrates by sticky coverings or specialized anchoring devices (Hynes 1976, p. 141; Stewart and Harper 1996, p. 217). Eggs may hatch within a few weeks or remain in diapause (dormancy) for much longer periods if environmental conditions, such as temperature, are not conducive to development (Hynes 1976, p. 142). Environmental conditions also may affect the growth and development of hatchlings (Stewart and Harper 1996, p. 217).

Summary of Biological Status and Threats

The Act directs us to determine whether any species is an endangered species or a threatened species because of any factors affecting its continued existence. In this section, we summarize the biological condition of these species and their resources, and the influences on such to assess both species' overall viability and the risks to that viability.

In considering what factors might constitute threats to a species, we must look beyond the exposure of the species to a factor to evaluate whether the species may respond to the factor in a way that causes actual impacts to the species. If there is exposure to a factor and the species responds negatively, the factor may be a threat and we attempt to determine how significant a threat it is. The threat is significant if it drives, or contributes to, the risk of extinction of the species such that the species warrants listing as endangered or threatened as those terms are defined in the Act.

Factor A. The Present or Threatened Destruction, Modification, or Curtailment of Its Habitat or Range

Meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies occupy remote, high-elevation alpine habitats in GNP and several proximate watersheds. The remoteness of these habitats largely precludes overlap with human uses and typical land management activities (e.g., forestry, mining, irrigation) that have historically modified habitats of many species. However, these relatively pristine, remote habitats are not expected to be immune to the effects of climate change. Thus, our analysis under Factor A focuses on the expected effects of climate change on meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly habitat and populations.

Climate Change

Our analyses under the Endangered Species Act include consideration of ongoing and projected changes in climate. The terms “climate” and Start Printed Page 68387“climate change” are defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The term “climate” refers to the mean and variability of different types of weather conditions over time, with 30 years being a typical period for such measurements, although shorter or longer periods also may be used (IPCC 2014, pp. 119-120). The term “climate change” thus refers to a change in the mean or variability of one or more measures of climate (e.g., temperature or precipitation) that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer, whether the change is due to natural variability, human activity, or both (IPCC 2014, p. 120).

Scientific measurements spanning several decades demonstrate that changes in climate are occurring; since the 1950s many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia (IPCC 2014, p. 40). Examples include warming of the global climate system, and substantial increases in precipitation in some regions of the world and decreases in other regions. (For these and other examples, see IPCC 2014, pp. 40-44; and Solomon et al. 2007, pp. 35-54, 82-85). Results of scientific analyses presented by the IPCC show that most of the observed increase in global average temperature since the mid-20th century cannot be explained by natural variability in climate, and is “extremely likely” (defined by the IPCC as 95 percent or higher probability) due to the observed increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere as a result of human activities, particularly carbon dioxide emissions from use of fossil fuels (IPCC 2014, p. 48 and figures 1.9 and 1.10; Solomon et al. 2007, pp. 21-35).

Scientists use a variety of climate models, which include consideration of natural processes and variability, as well as various scenarios of potential levels and timing of GHG emissions, to evaluate the causes of changes already observed and to project future changes in temperature and other climate conditions (e.g., Meehl et al. 2007, entire; Ganguly et al. 2009, pp. 11555, 15558; Prinn et al. 2011, pp. 527, 529). All combinations of models and emissions scenarios yield very similar projections of increases in the most common measure of climate change, average global surface temperature (commonly known as global warming), until about 2050 (IPCC 2014, p. 11; Ray et al. 2010, p. 11). Although projections of the magnitude and rate of warming differ after about 2050, the overall trajectory of all the projections is one of increased global warming through the end of this century, even for the projections based on scenarios that assume that GHG emissions will stabilize or decline. Thus, there is strong scientific support for projections that warming will continue through the 21st century, and that the magnitude and rate of change will be influenced substantially by the extent of GHG emissions (IPCC 2014, p. 57; Meehl et al. 2007, pp. 760-764 and 797-811; Ganguly et al. 2009, pp. 15555-15558; Prinn et al. 2011, pp. 527, 529). (See IPCC 2014, pp. 9-13, for a summary of other global projections of climate-related changes, such as frequency of heat waves and changes in precipitation.)

Various changes in climate may have direct or indirect effects on species. These effects may be positive, neutral, or negative, and they may change over time, depending on the species and other relevant considerations, such as interactions of climate with other variables (e.g., habitat fragmentation) (IPCC 2014, pp. 6-7; 10-14). Identifying likely effects often involves aspects of climate change vulnerability analysis. Vulnerability refers to the degree to which a species (or system) is susceptible to, and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes. Vulnerability is a function of the type, magnitude, and rate of climate change and variation to which a species is exposed, its sensitivity, and its adaptive capacity (IPCC 2014, pp. 70, 72; see also Glick et al. 2011, pp. 19-22). There is no single method for conducting such analyses that applies to all situations (Glick et al. 2011, p. 3). We use our expert judgment and appropriate analytical approaches to weigh relevant information, including uncertainty, in our consideration of various aspects of climate change.

As is the case with all stressors that we assess, even if we conclude that a species is currently affected or is likely to be affected in a negative way by one or more climate-related impacts, it does not necessarily follow that the species meets the definition of an “endangered species” or a “threatened species” under the Act. If a species is listed as endangered or threatened, knowledge regarding the vulnerability of the species to, and known or anticipated impacts from, climate-associated changes in environmental conditions can be used to help devise appropriate strategies for its recovery.

Global climate projections are informative, and, in some cases, the only or the best scientific information available for us to use. However, projected changes in climate and related impacts can vary substantially across and within different regions of the world (e.g., IPCC 2014, pp. 12, 14). Therefore, we use “downscaled” projections when they are available and have been developed through appropriate scientific procedures, because such projections provide higher resolution information that is more relevant to spatial scales used for analyses of a given species (see Glick et al. 2011, pp. 58-61, for a discussion of downscaling). With regard to our analysis for the meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly, downscaled projections are available.

Regional climate—The western United States appears to be warming faster than the global average. In the Pacific Northwest, regionally averaged temperatures have risen 0.8 °C (1.5 °F) over the last century and as much as 2 °C (4 °F) in some areas. Since 1900, the mean annual air temperature for GNP and the surrounding region has increased 1.3 °C (2.3 °F), which is 1.8 times the global mean increase (U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 2010, p. 1). Mean annual air temperatures are projected to increase by another 1.5 to 5.5 °C (3 to 10 °F) over the next 100 years (Karl et al. 2009, p. 135). Warming also appears to be pronounced in alpine regions globally (e.g., Hall and Fagre 2003, p. 134 and references therein). For the purposes of this finding, we consider the foreseeable future for anticipated effects of climate change on the alpine environment to be approximately 35 years (~year 2050) based on two factors. First, various global climate models (GCMs) and emissions scenarios provide consistent predictions within that timeframe (IPCC 2014, p. 11). Second, the effect of climate change on glaciers in GNP has been modeled within that timeframe (e.g., Hall and Fagre 2003, entire; Brown et al. 2010, entire).

Habitats for both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly originate from meltwater sources that will be impacted by any projected warming, including glaciers and small icefields, permanent and seasonal snowpack, alpine springs, and glacial lake outlets (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107; Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). The alteration or loss of these meltwater sources and perennial habitat has direct consequences on both meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly populations. Below, we provide an overview of expected rate of loss of meltwater sources in GNP as a result of climate change, followed by the predicted effects to stonefly habitat and populations from altered stream flows and water temperatures.Start Printed Page 68388

Glacier loss— Glacier loss in GNP is directly influenced by climate change (e.g., Hall and Fagre 2003, entire; Fagre 2005, entire). When established in 1910, GNP contained approximately 150 glaciers larger than 0.1 square kilometer (25 acres) in size, but presently only 25 glaciers larger than this size remain (Fagre 2005, pp. 1-3; USGS 2005, 2010). Hall and Fagre (2003, entire) modeled the effects of climate change on glaciers in GNP's Blackfoot-Jackson basin using then-current climate assumptions (i.e., doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide by 2030). Under this scenario, glaciers were predicted to completely melt in GNP by 2030, and predicted increases in winter precipitation due to climate change were not expected to buffer glacial shrinking (Hall and Fagre 2003, pp. 137-138). A more recent analysis of Sperry Glacier in GNP estimates this particular glacier may persist through 2080, in part due to annual avalanche inputs from an adjacent cirque wall (Brown et al. 2010, p. 5). We are not aware of any other published studies using more recent climate scenarios that speak directly to anticipated conditions of remaining glaciers in GNP. Thus, we largely rely on Hall and Fagre's 2003 predictions in our analysis, supplemented with more recent glacier-specific studies where appropriate (e.g., Brown et al. 2010, entire). However, we note that most climate scenarios developed since 2003 predict higher carbon dioxide concentrations (and thus greater warming and predicted effects) than those used in Hall and Fagre (2003).

Loss of other meltwater sources—Meltwater in meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly habitat is supplied by glaciers, as well as by four other sources: (1) Seasonal snow; (2) permanent snow; (3) alpine springs; and (4) ice masses (Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Seasonal snow is that which accumulates and melts seasonally, with the amount varying year to year depending on annual weather events. Permanent snow is some portion of a snowfield that does not generally melt on an annual basis, the volume of which can change over time. Alpine springs originate from some combination of meltwater from snow, ice masses or glaciers, and groundwater. Ice masses are smaller than glaciers and do not actively move as glaciers do.

The sources of meltwater that supply meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly habitat are expected to persist under a changing climate for varying durations. In general, we expect all meltwater sources to decline under a changing climate, given the relationship between climate and glacial melting (Hall and Fagre 2003, entire; Fagre 2005, entire) and recent climate observations and modeling (IPCC 2014, entire). It is likely that seasonal snowpack levels will be most immediately affected by climate change, as the frequency of more extreme weather events increases (IPCC 2014, p. 8). These extremes may result in increased seasonal snowpack in some years and reduced snowpack in others.

It is also expected that permanent snowpack and ice masses will decline and completely melt within the near future. The timing of their disappearance is expected to be before the majority of glacial melting (i.e., 2030), because permanent snowpack and ice masses are less dense than glaciers and typically have smaller volumes of snow and ice. However, alpine springs, at least those supplemented with groundwater, may continue to be present after complete glacial melting. We discuss the probable effects of declining meltwater from all sources on meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly habitat and populations in more detail below. Our analysis primarily focuses on effects to meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly populations within GNP. However, effects to meltwater lednian stonefly populations south of GNP are expected to be similar in magnitude and will likely occur sooner in time than those discussed for GNP, because the glaciers and ice/snow fields feeding occupied meltwater stonefly habitat in those areas are smaller in size, and thus likely to melt sooner than those in GNP.

Streamflows

Meltwater streams—Declines in meltwater sources are expected to affect flows in meltwater streams in GNP. Glaciers and other meltwater sources act as water banks, whose continual melt maintains streamflows during late summer or drought periods (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107). Following glacier loss, declines in streamflow and periodic dewatering events are expected to occur in meltwater streams in the northern Rocky Mountains (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 909). In similarly glaciated regions, intermittent stream flows have been documented following glacial recession and loss (Robinson et al. 2015, p. 8). By 2030, the modeled distribution of habitat with the highest likelihood of supporting meltwater lednian stonefly populations is predicted to decline by 81 percent in GNP, compared to present (Muhlfeld et al. 2011, p. 342). Desiccation (drying) of these habitats, even periodically, could eliminate entire populations of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly because nymphs need perennial flowing water to breathe and to mature before reproducing. Given that both stonefly species are believed to be poor dispersers, recolonization of previously occupied habitats is not expected following dewatering and extirpation events. Lack of recolonization by either stonefly species is expected to lead to further isolation between extant populations.

Fifty-three (of 58) meltwater lednian stonefly populations and one (of four) western glacier stonefly population occupy habitats supplied by seasonal snowpack, permanent snowpack, and ice masses, and some glaciers. Meltwater from these sources is expected to become inconsistent by 2030 (Hall and Fagre 2003, p. 137; Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Although the rate at which flows will be reduced or at which dewatering events will occur in these habitats is unclear, we expect, at a minimum, to see decreases in abundance and distribution of both species in those populations. By 2030, the remaining populations are expected to be further isolated and occupying marginal habitat.

Alpine springs—Declines in meltwater sources are also expected to affect flows in alpine springs, although likely on a longer time scale than for meltwater streams. Flow from alpine springs in the northern Rocky Mountains originates from glacial or snow meltwater in part, sometimes supplemented with groundwater (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107). For this reason, some alpine springs are expected to be more climate-resilient and persist longer than meltwater streams and may serve as refugia areas for meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, at least in the near-term (Ward 1994, p. 283). However, small aquifers feeding alpine springs are ultimately replenished by glacial and other meltwater sources in alpine environments (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 908).

Once glaciers in GNP melt, small aquifer volumes and the groundwater influence they provide to alpine springs are expected to decline. Thus by 2030, even flows from alpine springs supplemented with groundwater are expected to decline (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 910). This expected pattern of decline is consistent with observed patterns of low flow from alpine springs in the Rocky mountain region and other glaciated regions during years with little snowpack (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 910; Robinson et al. 2015, p. 9). Further, following complete melting of glaciers, Start Printed Page 68389drying of alpine springs in GNP might be expected if annual precipitation fails to recharge groundwater supplies. Changes in future precipitation levels due to climate change in the GNP region are predicted to range from relatively unchanged to a small (~10 percent) annual increase (IPCC 2014, pp. 20-21).

Only four populations of the meltwater lednian stonefly and two of the western glacier stonefly reside in streams originating from alpine springs. Thus, despite the potential for some alpine springs to provide refugia for both stonefly species even after glaciers melt, only a few populations may benefit from these potential refugia.

Glacial lake outlets—Similar to alpine springs, flow from glacial lake outlets is expected to diminish gradually following the complete melting of most glaciers around 2030. Glacial lakes are expected to receive annual inflow from melting snow from the preceding winter, although the amount by which it may be reduced after complete glacial melting is unknown. Reductions in flow from glacial lakes are expected to, at a minimum, decrease the amount of available habitat for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies.

One population each of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly occupies a glacial lake outlet (Upper Grinnell Lake; Giersch et al. 2015, p. 58, Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Thus, despite the fact that this habitat type may continue to provide refugia for both stonefly species even after the complete loss of glaciers, few populations may benefit from this potential refugia.

As such, we conclude that habitat degradation in the form of reduced streamflows due to the effects of climate change is a threat to the persistence of 89 percent of meltwater lednian stonefly and 25 percent of western glacier stonefly populations now and into the future.

Water Temperature

Meltwater streams— Glaciers act as water banks, whose continual melting maintains suitable water temperatures for meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly during late summer or drought periods (Hauer et al. 2007, p. 107; USGS 2010). As glaciers melt and contribute less volume of meltwater to streams, water temperatures are expected to rise (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 909). Aquatic invertebrates have specific temperature needs that influence their distribution (Fagre et al. 1997, p. 763; Lowe and Hauer 1999, pp. 1637, 1640, 1642; Hauer et al. 2007, p. 110); complete glacial melting may result in an increase in water temperatures above the physiological limits for survival or optimal growth for the meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies. As a result of melting glaciers and a lower volume of meltwater input into streams, we expect upward elevational shifts of meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly populations, as they track their optimal thermal preferences. However, both meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly already occupy the most upstream portions of these habitats and can move upstream only to the extent of the receding glacier/snowfield. Once the glaciers and snowfields completely melt, meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly will have no physical habitat left to which to migrate upstream. The likely result of this scenario would be the extirpation of these populations. If meltwater from seasonal precipitation accumulation remained after the complete loss of glaciers, displacement or extirpation of populations of both stonefly species could still occur due to thermal conditions that become unsuitable, encroaching aquatic invertebrate species that may be superior competitors, or changed thermal conditions that may favor the encroaching species in competitive interactions between the species (condition-specific competition).

The majority of meltwater lednian stonefly populations and one western glacier stonefly population occupy habitats that may warm significantly by 2030, due to the predicted complete melting of glaciers and snow/ice fields. Increasing water temperatures may be related to recent distributional declines of western glacier stoneflies within GNP (Giersch et al. 2015, p. 61). Thus, it is plausible that only those populations [6 meltwater lednian (11 percent of total known populations) and 3 western glacier stonefly (75 percent of total known populations)] occupying more climate-resilient habitat (e.g., springs, lake outlets, Sperry Glacier) may persist through 2030.

Alpine springs—Although meltwater contributions to alpine springs are expected to decline as glaciers and permanent snow melt, water temperature at the springhead may remain relatively consistent due to the influence of groundwater, at least in the short term. The springhead itself may provide refugia for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, although stream reaches below the actual springhead are expected to exhibit similar increases in water temperature in response to loss of glacial meltwater as those described for meltwater streams. However, as described above, some alpine springs may eventually dry up after glacier and snowpack loss, if annual precipitation fails to recharge groundwater supplies (Hauer et al. 1997, p. 910; Robinson et al. 2015, p. 9).

Only four populations of the meltwater lednian stonefly (7 percent of total known populations) and two of the western glacier stonefly (50 percent of total known populations) reside in streams originating from alpine springs. Thus, despite the fact that alpine springs may be more thermally stable than meltwater streams and provide thermal refugia to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly, only a few populations may benefit from this potential refugia.

Glacial lake outlets—Similar to alpine springs, glacial lake outlets are more thermally stable habitats than meltwater streams. This situation is likely due to the buffering effect of large volumes of glacial lake water supplying these habitats. It is anticipated that the buffering effects of glacial lakes will continue to limit increases in water temperature to outlet stream habitats, even after loss of glaciers. However, water temperatures are still expected to increase over time following complete glacial loss in GNP. It is unknown whether water temperature increases in glacial lake outlets will exceed presumed temperature thresholds for meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly in the near future. However, given the low water temperatures recorded in habitats where both species have been collected, even small increases in water temperature of glacial lake outlets may be biologically significant and detrimental to the persistence of both species.

One population each of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly occupies a glacial lake outlet (Upper Grinnell Lake; Giersch et al. 2015, p. 58, Giersch and Muhlfeld 2015, in progress). Thus, despite the fact that glacial lake outlets may be more thermally stable than meltwater streams and provide thermal refugia to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly, a small percentage of the overall population of each species may benefit from these potential refugia. Consequently, we conclude that changes in water temperature from climate change are a threat to most populations of both stonefly species now and into the future.Start Printed Page 68390

Maintenance and Improvement of Glacier National Park Infrastructure

Glacier National Park is managed to protect natural and cultural resources, and the landscape within the park is relatively pristine. However, the GNP does include a number of human-built facilities and structures that support visitor services, recreation, and access, such as the Going-to-the-Sun Road (which bisects GNP) and numerous visitor centers, trailheads, overlooks, and lodges (e.g., NPS 2003a, pp. S3, 11). Maintenance and improvement of these facilities and structures could conceivably lead to disturbance of the natural environment.

We are aware of one water diversion on Logan Creek that supplies water to the Logan Pass Visitor Center. This diversion is located several feet under the streambed in a segment of Logan Creek in which meltwater lednian stonefly is found. While the diversion has been operated for decades, recent surveys indicate relatively high densities of meltwater lednian stonefly in Logan Creek, particularly upstream of the diversion (NPS 2009, entire; Giersch 2016, pers. comm.). The diversion is scheduled to be retrofitted in 2017, in part to decrease instream withdrawals and increase efficiency. The diversion retrofit will likely include dewatering a short section of stream surrounding the intake structure, by diverting streamflow around the construction site. Minimization measures expected to be implemented as part of the diversion retrofit include relocation of meltwater lednian stoneflies out of the construction zone and using appropriate sedimentation control measures. Given the recent survey information indicating high densities of meltwater lednian stonefly in Logan Creek and the use of appropriate minimization measures, we have no evidence that the existing water diversion or retrofit project are a threat to meltwater lednian stonefly at the population level.

We do not have any information indicating that maintenance and improvement of other GNP facilities and structures is affecting either meltwater lednian or western glacier stoneflies or their habitat. While roads and trails provide avenues for recreationists (primarily hikers) to access backcountry areas, most habitats for both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly are located in steep, rocky areas that are not easily accessible, even from backcountry trails. Most documented occurrences of both species are in remote locations upstream from human-built structures, thereby precluding any impacts to stonefly habitat from maintenance or improvement of these structures. Given the above information, we conclude that maintenance and improvement of GNP facilities and structures, and the resulting improved access into the backcountry for recreationists, does not constitute a threat to the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly or their habitat now or in the near future.

Glacier National Park Visitor Impacts

In 2015, GNP hosted 2.3 million visitors (NPS 2015). Many of the recent collection sites for the meltwater lednian stonefly (e.g., Logan and Reynolds Creeks) are near visitor centers or adjacent to popular hiking trails. Theoretically, human activity (wading) in streams by anglers or hikers could disturb meltwater lednian stonefly habitat. However, we consider it unlikely that many GNP visitors would actually wade in stream habitats where the species has been collected, because the sites are in small, high-elevation streams situated in rugged terrain, and most would not be suitable for angling due to the absence of fish. In addition, the sites are typically snow covered into late July or August (Giersch 2010a, pers. comm.), making them accessible for only a few months annually. We also note that the most accessible collection sites in Logan Creek near the Logan Pass Visitor Center and the Going-to-the-Sun Road are currently closed to public use and entry to protect resident vegetation (NPS 2010, pp. J5, J24). We conclude that impacts to the meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly and their habitat from visitors to GNP do not constitute a threat now or in the near future.

Wilderness Area Visitor Impacts

Three populations of meltwater lednian stonefly are located in wilderness areas adjacent to GNP. Visitor activities in wilderness areas are similar to those described for GNP, namely hiking and angling. No recreational hiking trails are present near the two populations of meltwater lednian stonefly in the Bob Marshall wilderness and Great Bear wilderness (USFS 2015, p. 1) or near the population occurring in the Mission Mountain Tribal Wilderness. Similar to GNP, stream reaches that harbor the meltwater lednian stonefly in these wilderness areas are fishless, so wade anglers are not expected to disturb stonefly habitat. Given the remote nature of and limited access to meltwater stonefly habitat in wilderness areas adjacent to GNP, we do not anticipate any current or future threats to meltwater lednian stoneflies or their habitat from visitor use.

Summary of Factor A

In summary, we expect climate change to fragment or degrade all habitat types that are currently occupied by meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies, albeit at different rates. Flows in meltwater streams are expected to be affected first, by becoming periodically intermittent and warmer. Drying of meltwater streams and water temperature increases, even periodically, are expected to reduce available habitat for the meltwater lednian stonefly by 81 percent by 2030. After 2030, flow reductions and water temperature increases due to continued warming are expected to further reduce or degrade remaining refugia habitat (alpine springs and glacial lake outlets) for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies. Predicted habitat changes are based on observed patterns of flow and water temperature in similar watersheds within GNP and elsewhere where glaciers have already melted.

In addition, we have observed a declining trend in western glacier stonefly distribution over the last 50 years, as air temperatures have warmed in GNP. We expect the meltwater lednian stonefly to follow a similar trajectory, given the similarities between the two stonefly species and their meltwater habitats. Consequently, we conclude that habitat fragmentation and degradation resulting from climate change is a threat to both the meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies now and into the near future. Given the minimal overlap between stonefly habitat and most existing infrastructure or backcountry activities (e.g., hiking), we conclude any impacts from these activities do not constitute a threat to either the meltwater lednian stonefly or the western glacier stonefly. The sole water diversion present on Logan Creek and the upcoming retrofit project also do not appear to be threats to meltwater lednian stonefly, given that recent surveys have documented high densities of meltwater lednian stonefly near the diversion, and the expected use of appropriate minimization measures for the retrofit project.

Factor B. Overutilization for Commercial, Recreational, Scientific, or Educational Purposes

We are not aware of any threats involving the overutilization or collection of the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly for any commercial, recreational, or educational purposes at this time. We are aware that specimens of both species are Start Printed Page 68391occasionally collected for scientific purposes to determine their distribution and abundance (e.g., Baumann and Stewart 1980, pp. 655, 658; NPS 2009; Muhlfeld et al. 2011, entire; Giersch et al. 2015, entire). However both species are comparatively abundant in remaining habitats (e.g., NPS 2009; Giersch 2016, pers. comm.), and we have no information to suggest that past, current, or any collections in the near future will result in population-level effects to either species. Consequently, we do not consider overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes to be a threat to the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly now or in the near future.

Factor C. Disease or Predation

We are not aware of any diseases that affect the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly. Therefore, we do not consider disease to be a threat to these species now or in the near future.

We presume that nymph and adult meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies may occasionally be subject to predation by bird species such as American dipper (Cinclus mexicanus) or predatory aquatic insects. Fish and amphibians are not potential predators because these species do not occur in the stream reaches containing the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly. The American dipper prefers to feed on aquatic invertebrates in fast-moving, clear alpine streams (MNHP 2010b), and the species is native to GNP. As such, predation by American dipper on these species would represent a natural ecological interaction in the GNP (see Synergistic Effects section below for analysis on potential predation/habitat fragmentation synergy). Similarly, predation by other aquatic insects would represent a natural ecological interaction between the species. We have no evidence that the extent of such predation, if it occurs, represents any population-level threat to either meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly, especially given that densities of individuals within many of these populations are high. Therefore, we do not consider predation to be a threat to these species now or in the near future.

In summary, the best available scientific and commercial information does not indicate that the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly is affected by any diseases, or that natural predation occurs at levels likely to negatively affect either species at the population level. Therefore, we do not find disease or predation to be threats to the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly now or in the near future.

Factor D. The Inadequacy of Existing Regulatory Mechanisms

Section 4(b)(1)(A) of the Endangered Species Act requires the Service to take into account “those efforts, if any, being made by any State or foreign nation, or any political subdivision of a State or foreign nation, to protect such species....” We consider relevant Federal, State, and Tribal laws and regulations when evaluating the status of the species. Only existing ordinances, regulations, and laws that have a direct connection to a law are enforceable and permitted are discussed in this section. No local, State, or Federal laws specifically protect the meltwater lednian or western glacier stonefly.

National Environmental Policy Act

All Federal agencies are required to adhere to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1970 (42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq.) for projects they fund, authorize, or carry out. NEPA is a procedural statute, which requires Federal agencies to formally document and publicly disclose the environmental impacts of their actions and management decisions. Documentation for NEPA is provided in an environmental impact statement, an environmental assessment, or a categorical exclusion. NEPA does not require that adverse impacts be mitigated. Our review finds that it is likely that there would be very few activities that would trigger NEPA's disclosure requirements. However, NEPA does not require protection of a species or its habitat, and does not require the selection of a particular course of action.

National Park Service Organic Act

The NPS Organic Act of 1916 54 U.S.C. 100101 (et seq.), as amended, states that the NPS “shall promote and regulate the use of the National Park System by means and measures that conform to the fundamental purpose of the System units, which purpose is to conserve the scenery, natural and historic objects, and wild life in the System units and to provide for the enjoyment of the scenery, natural and historic objects, and wild life in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Given that the vast majority of occurrences of the meltwater lednian stonefly (>90 percent) and all occurrences of the western glacier stonefly are within the boundaries of GNP, the NPS Organic Act is one Federal law of particular relevance to both species. Although the GNP does not have a management plan specific to either stonefly species, the habitats occupied by the species remain relatively pristine and generally free from direct human impacts from Park visitors (see Threat Factor A). We also note that the most accessible meltwater lednian stonefly collection sites in Logan Creek near the Logan Pass Visitor Center and the Going-to-the-Sun Road are currently closed to public use and entry to protect resident vegetation pursuant to GNP management regulations (NPS 2010, pp. J5, J24).

Regulatory Mechanisms To Limit Glacier Loss

National and international regulatory mechanisms to comprehensively address the causes of climate change are continuing to be developed. Domestic U.S. efforts relative to climate change focus on implementation of the Clean Air Act, and continued studies, programs, support for developing new technologies, and use of incentives for supporting reductions in emissions. While not regulatory, international efforts to address climate change globally began with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted in May 1992. The stated objective of the UNFCCC is the stabilization of GHG concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. However, we note that greenhouse gas loading in the atmosphere can have a considerable lag effect on climate, so that what has already been emitted will have impacts out to 2100 and beyond (IPCC 2014, pp. 56-57).

National Forest Management Act

The National Forest Management Act (NFMA; 16 U.S.C. 1600-1614, as amended) requires the Secretary of the Department of Agriculture to develop and implement resource management plans for each unit of the National Forest System. The Forest Service has developed a land management plan for the Flathead National Forest, including the wilderness portions containing meltwater stonefly populations, that designates conservation of sensitive, endangered and threatened species as a high priority (USFS 2001, p. III-109). In addition, only natural agents (fire, wind, insects, etc.) are permitted to alter the vegetation or habitat within the wilderness portions of the Flathead National Forest (USFS 2001, p. III-109). As such, the wilderness areas on Flathead National Forest are managed for natural ecological processes to maintain wilderness character.Start Printed Page 68392

Wilderness Act

The Wilderness Act of 1964 (16 U.S.C. 1131-1136, 78 Stat. 890) provides that areas designated by Congress as “wilderness areas” “shall be administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness. . . .” The Act also directed the Secretary of the Interior to review and make recommendations to the President about the suitability of particular lands for preservation as wilderness, with the final decision being made by Congress (16 U.S.C. 1132(c)). These lands are managed under the nonimpairment standard to ensure that they retain their wilderness character until Congress makes a decision. Areas where the meltwater lednian stonefly occurs within Flathead National Forest are designated as wilderness. Areas where the meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies occur within GNP were nominated for protection as wilderness in 1974, but Congress has not rendered a decision. Pursuant to NPS policy, the proposed wilderness lands are managed as wilderness (NPS Management Policy § 6.3 (2006)).

The Wilderness Act establishes restrictions on land use activities that can be undertaken on a designated area. In particular, such lands are managed to preserve their wilderness character, and many activities that might otherwise be permitted are prohibited on lands designated as wilderness (e.g., commercial enterprise, roads, logging, mining, oil/gas exploration) (16 U.S.C. 1133(c)).

Flathead Indian Reservation Fishing, Bird Hunting, and Recreation Regulations

The Confederated Kootenai Salish Tribes manage land on the Flathead Reservation and are currently implementing “Flathead Indian Reservation Fishing, Bird Hunting, and Recreation Regulations,” which, in part, regulate recreation in the Mission Mountain Tribal Wilderness Area (MMTW), where one population of the meltwater lednian stonefly occurs. Some relevant regulations preclude the removal of natural items from the MMTW and restrict certain activities within 30 m (100 ft) of water sources.

Factor E. Other Natural or Manmade Factors Affecting Its Continued Existence

Small Population Size

A principle of conservation biology is that the presence of larger and more productive (resilient) populations can reduce overall extinction risk. To minimize extinction risk, genetic diversity should be maintained (Fausch et al. 2006, p. 23; Allendorf et al. 1997, entire). Both meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly populations exist as presumably isolated populations, given that most populations are separated by considerable distances (i.e., miles) and stoneflies in general are poor dispersers (on the order of tens of meters). Population isolation can limit or preclude genetic exchange between populations (Fausch et al. 2006, p. 8). However, densities within many of these populations are high (Giersch 2016, pers. comm.), which may offset or delay, at least in part, deleterious genetic effects from population isolation. Given the lack of genetic information for both meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly, and the relatively high densities observed in many of the populations, we conclude that the effects of small population size (as a standalone issue) is not a threat now or in the near future.

Restricted Range and Stochastic (Random) Events

Narrow endemic species, such as the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly, can be at risk of extirpation from random events such as fire, flooding, or drought. Random events occurring within the narrow range of endemic species have the potential to disproportionately affect large numbers of individuals or populations, relative to a more widely dispersed species. The risk to meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly populations from fire appears low, given that most alpine environments in GNP have few trees and little vegetation to burn. The risk to both species from flooding also appears low, given the relatively small watershed areas available to capture and channel precipitation upslope of most stonefly populations.

The risk to the meltwater lednian stonefly from drought appears moderate in the near term because 20 of the 58 known populations occupy habitats supplied by seasonal snowmelt, which would be expected to decline during drought. For the western glacier stonefly, the threat of drought is also moderate because one of the four known populations is likely to be affected by variations in seasonal precipitation and snowpack. The risk of drought in the longer term (after 2030 and when complete loss of glaciers is predicted) appears high for both stonefly species. Once glaciers melt, drought or extended drought could result in dewatering events in some habitats. Dewatering events would likely extirpate entire populations almost instantaneously. Natural recolonization of habitats affected by drought is unlikely, given the poor dispersal abilities of both stonefly species and general isolation of populations relative to one another (Hauer et al. 2007, pp. 108-110). Thus, we conclude that drought (a stochastic event) will be a threat to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly in the near future.

Summary of Factor E

The effect of small population size does not appear to be a current or future threat to the meltwater lednian stonefly or the western glacier stonefly, given the high densities of individuals within most populations. However, the restricted range of the meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly make both species vulnerable to the stochastic threat of drought. Although not considered a current threat, drought will likely affect both species negatively within the near future. There is potential for extirpation of entire populations of both species as a result of dewatering events caused by drought, after the complete loss of glaciers predicted by 2030. Thus, drought is considered a threat to both the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly within the near future.

Synergistic Effects

Climate change may interact with other potential stressors and compound negative effects on meltwater lednian stonefly and western glacier stonefly populations. We limit our discussion here to factors that are not implicitly linked, and whose effects are not accounted for, in our previous analysis regarding climate change.

Climate Change and Predation

Previously, we presumed that nymph and adult meltwater lednian and western glacier stoneflies may occasionally be subject to predation by bird species such as American dipper or predatory aquatic insects. As such, predation by American dipper or predatory aquatic insects on these species would represent a natural ecological interaction in the GNP and surrounding areas. However, habitat fragmentation and degradation resulting from climate change may create different scenarios where populations of the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly remain in isolated pockets of habitat, in thermally marginal habitat, or both, and are Start Printed Page 68393exposed to relative increased levels of predation. In such cases, the ability of the meltwater lednian stonefly or the western glacier stonefly to persist could theoretically be compromised by the cumulative effects resulting from the two pressures acting synergistically. Below, we evaluate the possibility of these scenarios in more detail.

In the first scenario, the meltwater lednian stonefly or the western glacier stonefly may occupy small, isolated pockets (or pools) of habitat resulting from fragmentation (e.g., springheads). Under this scenario, predation from both American dippers and aquatic predatory insects could result in population-level effects of either species in these habitats. However, this situation appears unlikely for several reasons. First, the microhabitat features (rocks, bark) present that allow the meltwater lednian stonefly and the western glacier stonefly to evade predation would likely still be present, albeit in smaller quantities. Thus, even with increased predation pressure within a confined stream pool, both species would likely still utilize available habitat features to survive and fulfill life-history needs. Second, assuming thermal regimes are still within physiological limits, both stonefly species would likely use the same behavioral strategies they currently use to persist (e.g., timing of foraging, resting, and reproducing). In this scenario, population densities could potentially be reduced beyond what would be expected in more contiguous habitat, but population-level effects from predation appear unlikely, especially given the high densities of individuals within many of these populations.

In a second scenario, physical habitat extent may remain intact, but thermal conditions may be altered (e.g., water temperature has increased significantly). In this case, increased water temperatures may interfere with the ability of the meltwater lednian stonefly or the western glacier stonefly to rely on behavioral strategies to evade predation effectively. Individuals may be forced to forage or move at inopportune times, resulting in higher predation levels and likely lower reproductive success. However, increases in water temperature may also affect the behavioral strategies (foraging) of aquatic predatory insects similar to that of the meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly. It appears unlikely that the predatory abilities of American dipper would be affected by increased water temperature. However, it is unclear how efficient American dippers are as stonefly predators and whether they could exert enough predation pressure to rise to a population-level effect for the meltwater lednian and western glacier stonefly.