2024-09989. Medicare Program; Alternative Payment Model Updates and the Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Model

-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 43518

AGENCY:

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

ACTION:

Proposed rule.

SUMMARY:

This proposed rule describes a new mandatory Medicare payment model, the Increasing Organ Transplant Access Model (IOTA Model), that would test whether performance-based incentive payments paid to or owed by participating kidney transplant hospitals increase access to kidney transplants for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) while preserving or enhancing the quality of care and reducing Medicare expenditures. This proposed rule also includes standard provisions that would apply to Innovation Center models whose first performance period begins on or after January 1, 2025, and also would apply, in whole or part, to any Innovation Center model whose first performance period begins prior to January 1, 2025 should such model's governing documentation incorporate the provisions by reference in whole or in part. The proposed standard provisions relate to beneficiary protections; cooperation in model evaluation and monitoring; audits and records retention; rights in data and intellectual property; monitoring and compliance; remedial action; model termination by CMS; limitations on review; miscellaneous provisions on bankruptcy and other notifications; and the reconsideration review process.

DATES:

To be assured consideration, comments must be received at one of the addresses provided below, by July 16, 2024.

ADDRESSES:

In commenting, please refer to file code CMS-5535-P.

Comments, including mass comment submissions, must be submitted in one of the following three ways (please choose only one of the ways listed):

1. Electronically. You may submit electronic comments on this regulation to http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the “Submit a comment” instructions.

2. By regular mail. You may mail written comments to the following address ONLY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services, Attention: CMS-5535-P, P.O. Box 8013, Baltimore, MD 21244-8013.

Please allow sufficient time for mailed comments to be received before the close of the comment period.

3. By express or overnight mail. You may send written comments to the following address ONLY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services,Department of Health and Human Services, Attention: CMS-5535-P, Mail Stop C4-26-05, 7500 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, MD 21244-1850.

For information on viewing public comments, see the beginning of the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION section.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

CMMItransplant@cms.hhs.gov for questions related to the Increasing Organ Transplant Access Model.

CMMI-StandardProvisions@cms.hhs.gov for questions related to the Standard Provisions for Innovation Center Models.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Inspection of Public Comments: All comments received before the close of the comment period are available for viewing by the public, including any personally identifiable or confidential business information that is included in a comment. We post all comments received before the close of the comment period on the following website as soon as possible after they have been received: http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the search instructions on that website to view public comments. CMS will not post on Regulations.gov public comments that make threats to individuals or institutions or suggest that the commenter will take actions to harm an individual. CMS encourages individuals not to submit duplicative comments. We will post acceptable comments from multiple unique commenters even if the content is identical or nearly identical to other comments.

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Copyright Notice

Throughout this proposed rule, we use CPT® codes and descriptions to refer to a variety of services. We note that CPT® codes and descriptions are copyright 2020 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. CPT® is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association (AMA). Applicable Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and Defense Federal Acquisition Regulations (DFAR) apply.

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose

Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (the Act) gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services the authority to test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditures in Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) while preserving or enhancing the quality of care furnished to individuals covered by such programs. This proposed rule describes a new mandatory Medicare payment model to be tested under section 1115A of the Act—the Increasing Organ Transplant Access Model (IOTA Model)—which would begin on January 1, 2025 and end on December 31, 2030. In this proposed rule, we propose payment policies, participation requirements, and other provisions to test the IOTA Model. We propose to test whether performance-based incentives (including both upside and downside risk) for participating kidney transplant hospitals can increase the number of kidney transplants (including both living donor and deceased donor transplants) furnished to End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) patients, encourage investments in care processes and patterns with respect to patients who need kidney transplants, encourage investments in value-based care and improvement activities, and promote kidney transplant hospital accountability by tying payments to value. The IOTA Model is also intended to advance health equity by improving equitable access to the transplantation ecosystem through design features such as a proposed health equity plan requirement to address health outcome disparities and a health equity performance adjustment.

This proposed rule also includes proposed standard provisions that would apply to Innovation Center models whose first performance periods begin on or after January 1, 2025, unless otherwise specified in a model's governing documentation, as well as to Innovation Center models whose first performance periods begin prior to January 1, 2025, provided the standard provisions are incorporated into such models' governing documentation. The proposed standard provisions address beneficiary protections; cooperation in model evaluation and monitoring; audits and record retention; rights in data and intellectual property; monitoring and compliance; remedial action; model termination by CMS; limitations on review; miscellaneous provisions on bankruptcy and other Start Printed Page 43519 notifications; and the reconsideration review process.

We seek public comment on these proposals, the alternatives considered, and the request for information (RFI) in section III.D. of this proposed rule.

B. Summary of the Proposed Provisions

1. Standard Provisions for Innovation Center Models

The proposed standard provisions for Innovation Center models would be applicable to all Innovation Center models whose first performance periods begin on or after January 1, 2025, subject to any limitations specified in a model's governing documentation. The proposed standard provisions also would apply to all Innovation Center models whose first performance periods begin prior to January 1, 2025, provided the standard provisions are incorporated into such models' governing documentation.

We are proposing to codify these standard provisions to increase transparency, efficiency, and clarity in the operation and governance of Innovation Center models, and to avoid the need to restate the provisions in each model's governing documentation. The proposed standard provisions include terms that have been repeatedly memorialized, with minimal variation, in existing models' governing documentation. The proposed standard provisions are not intended to encompass all of the terms and conditions that would apply to each Innovation Center model, because each model embodies unique design features and implementation plans that may require additional, more tailored provisions, including with respect to payment methodology, care delivery and quality measurement, that would continue to be included in each model's governing documentation. Model-specific provisions applicable to the IOTA Model proposed herein are described in section III of this proposed rule.

2. Model Overview—Proposed Increasing Organ Transplant Access Model

a. Proposed IOTA Model Overview

End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) is a medical condition in which a person's kidneys cease functioning on a permanent basis, leading to the need for a regular course of long-term dialysis or a kidney transplant to maintain life.[1] The best treatment for most patients with kidney failure is kidney transplantation. Nearly 808,000 people in the United States are living with ESRD, with about 69 percent on dialysis and 31 percent with a kidney transplant.[2] For ESRD patients, regular dialysis sessions or a kidney transplant is required for survival. Relative to dialysis, a kidney transplant can improve survival, reduce avoidable health care utilization and hospital acquired conditions, improve quality of life, and lower Medicare expenditures.[3] [4] However, despite these benefits, evidence shows low rates of ESRD patients placed on kidney transplant hospitals' waitlists, a decline in living donors over the past 20 years, and underutilization of available donor kidneys, coupled with increasing rates of donor kidney discards, and wide variation in kidney offer acceptance rates and donor kidney discards by region and across kidney transplant hospitals.[5] [6] Further, there are substantial disparities in both deceased and living donor transplantation rates among structurally disadvantaged populations. Strengthening and improving the performance of the organ transplantation system is a priority for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Consistent with this priority, and through joint efforts with HHS' Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the proposed IOTA Model would aim to reduce Medicare expenditures and improve performance and equity in kidney transplantation by creating performance-based incentive payments for participating kidney transplant hospitals tied to access and quality of care for ESRD patients on the hospitals' waitlists.

The proposed IOTA Model would be a mandatory model that would begin on January 1, 2025 and end on December 31, 2030, resulting in a 6-year model performance period (“model performance period”) comprised of 6 individual performance years (each a “performance year” or “PY”). The proposed IOTA Model would test whether performance-based incentives paid to, or owed by, participating kidney transplant hospitals can increase access to kidney transplants for patients with ESRD, while preserving or enhancing quality of care and reducing Medicare expenditures. CMS would select kidney transplant hospitals to participate in the IOTA Model through the methodology proposed in section III.C.3.d of this proposed rule. As this would be a mandatory model, the selected kidney transplant hospitals would be required to participate. CMS would measure and assess the participating kidney transplant hospitals' performance during each PY across three performance domains: achievement, efficiency, and quality.

The achievement domain would assess each participating kidney transplant hospital on the overall number of kidney transplants performed during a PY, relative to a participant-specific target. The efficiency domain would assess the kidney organ offer acceptance rates of each participating kidney transplant hospital relative to the national rate. The quality domain would assess the quality of care provided by the participating kidney transplant hospitals across a set of proposed outcome metrics and quality measures. Each participating kidney transplant hospital's performance score across these three domains would determine its final performance score and corresponding amount for the performance-based incentive payment that CMS would pay to, or the payment that would be owed by, the participating kidney transplant hospital. The proposed upside risk payment would be a lump sum payment paid by CMS after the end of a PY to a participating kidney transplant hospital with a final performance score of 60 or greater. Conversely, beginning after PY 2, the downside risk payment would be a lump sum payment paid to CMS by any participating kidney transplant hospital Start Printed Page 43520 with a final performance score of 40 or lower. We are not proposing a downside risk payment for PY 1 of the model.

b. Model Scope

We propose that participation in the IOTA Model would be mandatory for 50 percent of all eligible kidney transplant hospitals in the United States. We anticipate that a total of approximately 90 kidney transplant hospitals will be selected to participate in the IOTA Model. As discussed in section III.C.3.b. of this proposed rule, we believe that mandatory participation is necessary to minimize the potential for selection bias and to ensure a representative sample size nationally, thereby guaranteeing that there will be adequate data to evaluate the model test.

We propose that eligible kidney transplant hospitals would be those that: (1) performed at least eleven kidney transplants for patients 18 years of age or older annually regardless of payer type during the three-year period ending 12 months before the model's start date; and (2) furnished more than 50 percent of the hospital's annual kidney transplants to patients 18 years of age or older during that same period. We propose to select the kidney transplant hospitals that will be required to participate in the IOTA Model from the group of eligible kidney transplant hospitals using a stratified random sampling of donation service areas (“DSAs”) to ensure that there is a fair selection process and representative group of participating kidney transplant hospitals. For the purposes of this proposed rule, a DSA has the same meaning given to that term at 42 CFR 486.302.

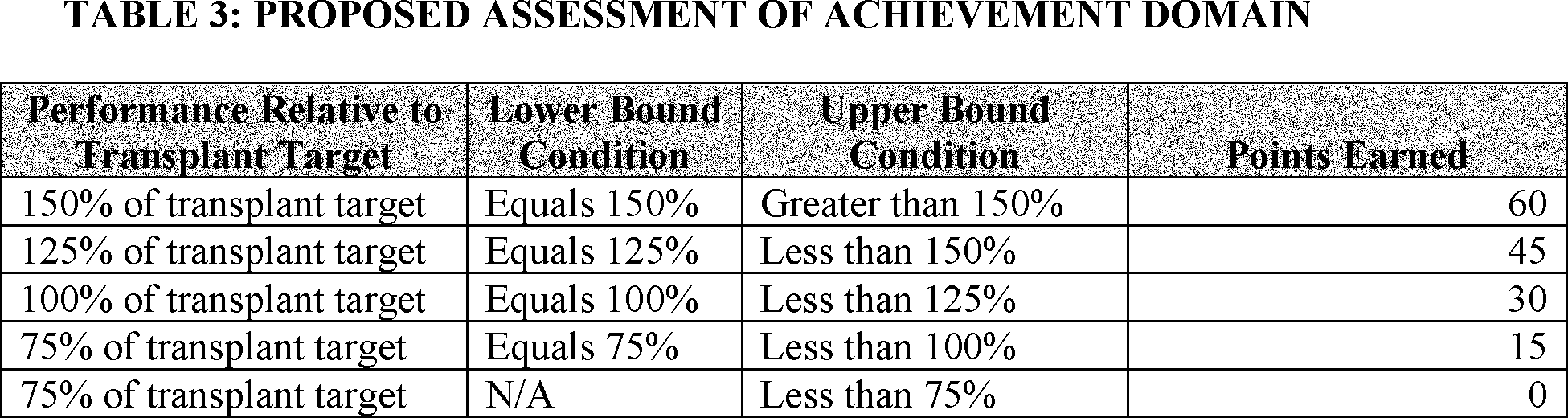

c. Performance Assessment

We propose to assess each IOTA participants' performance across three performance domains during each PY of the model, with a maximum possible final performance score of 100 points. The three performance domains would include: (1) an achievement domain worth up to 60 points, (2) an efficiency domain worth up to 20 points, and (3) a quality domain worth up to 20 points.

The achievement domain would assess the number of kidney transplants performed by each IOTA participant for attributed patients, with performance on this domain worth up to 60 points. The final performance score would be heavily weighted on the achievement domain to align with the IOTA Model's goal to increase access to kidney transplants. The IOTA Model theorizes that improvement activities, including those aimed at reducing unnecessary deceased donor discards and increasing living donors, may help increase access to kidney transplants.

We propose that CMS would set a target number of kidney transplants for each IOTA participant for each PY to measure the IOTA participant's performance in the achievement domain (the “transplant target”), as described in section III.C.5.c of this proposed rule. Each IOTA participant's transplant target for a given PY would be based on the IOTA participant's historical volume of deceased and living donor transplants furnished to attributed patients in the relevant baseline years, adjusted by the national trend rate in the number of kidney transplants performed and further adjusted by the proportion of transplants furnished by the IOTA participant to attributed patients who are low income. Section III.C.5.c. of this proposed rule describes the variation in the number of kidney transplants performed across kidney transplant hospitals, which would make it challenging to set transplant targets on a regional or national basis. The IOTA Model would therefore set a transplant target that is specific to each IOTA participant to address this concern, while still accounting for the national trend rate in the number of kidney transplants performed. It is expected that IOTA participants' transplant targets may change from PY to PY because of the way in which the transplant target would be calculated.

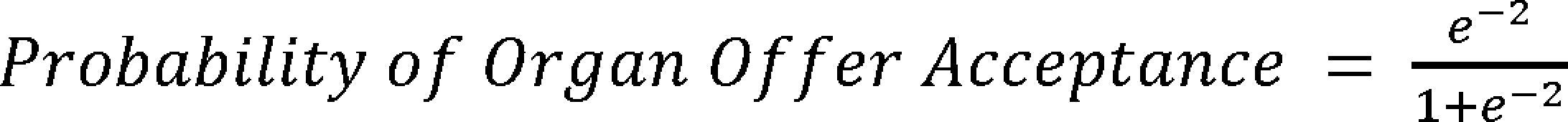

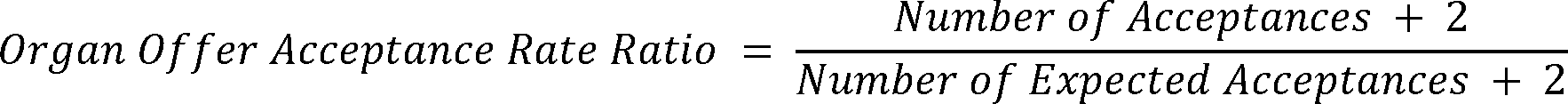

The efficiency domain would assess the kidney organ offer acceptance rate ratio for each IOTA participant. The kidney organ offer acceptance rate ratio measures the number of kidneys an IOTA participant accepts for transplant over the expected value, based on variables such as kidney quality. Points for the kidney organ offer acceptance rate ratio would be determined relative to either the kidney organ offer acceptance rate ratio across all kidney transplant hospitals, or the IOTA participant's own past kidney organ offer acceptance rate ratio, with performance on the efficiency domain being worth up to 20 points.

Finally, the quality domain would assess IOTA participants' performance on post-transplant outcomes in addition to three quality measures—the CollaboRATE Shared Decision-Making Score, Colorectal Cancer Screening, and the 3-Item Care Transition Measure, with performance on this domain being worth up to 20 points.

Each IOTA participant's final performance score would be the sum of the points earned for each domain: achievement, efficiency, and quality. The final performance score in a PY would be determinative of whether the IOTA participant would be eligible to receive an upside risk payment from CMS, fall into the neutral zone where no upside or downside risk payment would apply, or owe a downside risk payment to CMS for the PY as described in section III.C.6. of this proposed rule.

d. Performance-Based Incentive Payment Formula

Each IOTA participant's final performance score would determine whether: (1) CMS would pay an upside risk payment to the IOTA participant; (2) the IOTA participant would fall into a neutral zone, in which case no performance-based incentive payment would be paid to or owed by the IOTA participant; or (3) the IOTA participant would owe a downside risk payment to CMS. For a final performance score above 60, CMS would apply the formula for the upside risk payment, which we propose would be equal to the IOTA participant's final performance score minus 60, then divided by 60, then multiplied by $8,000, then multiplied by the number of kidney transplants furnished by the IOTA participant to attributed patients with Medicare as their primary or secondary payer during the PY. Final performance scores below 60 in PY 1 and final performance scores of 41 to 59 in PYs 2-6 would fall in the neutral zone where there would be no payment owed to the IOTA participant or CMS.

We propose to phase-in the downside risk payment beginning in PY2. We explain in section III.C.5.b. of this proposed rule that new entrants to value-based payment models may need a ramp up period before they are able to accept downside risk. Thus, the IOTA Model proposes an upside risk-only approach for PY 1 as an incentive in each of the three performance domains. This would give IOTA participants time to consider, invest in, and implement value-based care and quality improvement initiatives before downside risk payments would begin. Beginning in PY 2, for a final performance score of 40 and below, CMS would apply the formula for the downside risk payment, which would be equal to the IOTA participant's final performance score minus 40, then divided by 40, then multiplied by −$2,000, then multiplied by the number of kidney transplants furnished by the IOTA participant to attributed patients with Medicare as their primary or secondary payer during the PY.

CMS would pay the upside risk payment in lump sum to the IOTA participant after the PY. The IOTA participant would pay the downside Start Printed Page 43521 risk payment to CMS in a lump sum after the PY.

e. Data Sharing

We propose to collect certain quality, clinical, and administrative data from IOTA participants for model monitoring and evaluation activities under the authority in 42 CFR 403.1110(b). We would also share certain data with IOTA participants upon request as described in section III.C.3.a. of this proposed rule and as permitted by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule and other applicable law. We propose to offer each IOTA participant the opportunity to request certain beneficiary-identifiable data for their attributed Medicare beneficiaries for treatment, case management, care coordination, quality improvement activities, and population-based activities relating to improving health or reducing health care costs, as permitted by 45 CFR 164.506(c). The data uses and sharing would be allowed only to the extent permitted by the HIPAA Privacy Rule and other applicable law and CMS policies. We also propose to share certain aggregate, de-identified data with IOTA participants.

f. Other Requirements

We propose several other model requirements for selected transplant hospitals, including transparency requirements, public reporting requirements, and a health equity plan requirement which would be optional for PY1 and required for PY 2 through PY 6, as described in section III.C.8. of this proposed rule.

(1) Transparency Requirements

Patients are often unsure whether they qualify for a kidney transplant at a given kidney transplant hospital. We propose that IOTA participants would be required to publish on a public facing website the criteria they use when determining whether or not to add a patient to the kidney transplant waitlist. We also propose to add requirements to facilitate increased transparency for patients regarding the organ offers received on the patient's behalf while the patient is on the waitlist. Specifically, we propose that IOTA participants would be required to inform patients on the waitlist, on a monthly basis, of the number of times an organ was declined on each patient's behalf and the reason(s) why each organ was declined. We believe that notifying patients of the organs declined on their behalf would encourage conversations between patients and their providers regarding a patient's preferences for transplant and facilitate better shared decision-making.

(2) Health Equity Requirements

We propose that during the model's first PY, each IOTA participant would have the option to submit a health equity plan (“HEP”) to CMS. We propose that each IOTA participant would then be required to submit a HEP to CMS for PY 2 and to update its HEP for each subsequent PY. We propose that the IOTA participant's HEP would identify health disparities within the IOTA participant's population of attributed patients and outline a course of action to address them.

We also considered proposing to require IOTA participants to collect and report patient-level health equity data to CMS. Specifically, we considered proposing that IOTA participants would be required to conduct health related social needs screening for at least three core areas—food security, housing, and transportation. We recognize these areas as some of the most common barriers to kidney transplantation and the most pertinent health related social needs for the IOTA patient population.[7] We have included an RFI in this proposed rule to solicit feedback and comment on such a requirement.

g. Medicare Payment Waivers and Additional Flexibilities

We believe it is necessary to waive certain requirements of title XVIII of the Act solely for purposes of carrying out the testing of the IOTA Model under section 1115A of the Act. We propose to issue these waivers using our waiver authority under section 1115A(d)(1) of the Act. Each of the proposed waivers is discussed in detail in section III.C.10. of this proposed rule.

h. Overlaps With Other Innovation Center Models and CMS Programs

We expect that there could be situations where a Medicare beneficiary attributed to an IOTA participant is also assigned, aligned, or attributed to another Innovation Center model or CMS program. Overlap could also occur among providers and suppliers at the individual or organization level, such as where an IOTA participant or one of their providers would participate in multiple Innovation Center models. We believe that the IOTA Model would be compatible with existing models and programs that provide opportunities to improve care and reduce spending. The IOTA Model would not be replacing any covered services or changing the payments that participating hospitals receive through the inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) or outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS). Rather, the IOTA Model proposes performance-based payments separate from what participants would be paid by CMS for furnishing kidney transplants to Medicare beneficiaries. Additionally, we would work to resolve any potential overlaps between the IOTA Model and other Innovation Center models or CMS programs that could result in duplicative payments for services, or duplicative counting of savings or other reductions in expenditures. Therefore, we propose to allow overlaps between the IOTA Model and other Innovation Center models and CMS programs.

i. Monitoring

We propose to closely monitor the implementation and outcomes of the IOTA Model throughout its duration consistent with the monitoring requirements proposed in the Standard Provisions for Innovation Center models in section II of this proposed rule and the proposed requirements in section III.C.13. of this proposed rule. The purpose of this monitoring would be to ensure that the IOTA Model is implemented safely and appropriately, that the quality and experience of care for beneficiaries is not harmed, and that adequate patient and program integrity safeguards are in place.

j. Beneficiary Protections

As proposed in section III.C.10. of this proposed rule, CMS would not allow beneficiaries or patients to opt out of attribution to an IOTA participant; however, the IOTA Model would not restrict a beneficiary's freedom to choose another kidney transplant hospital, or any other provider or supplier for healthcare services, and IOTA participants would be subject to the Standard Provisions for Innovation Center Models outlined in section II. of this proposed rule protecting Medicare beneficiary freedom of choice and access to medically necessary services. We also would require that IOTA participants notify Medicare beneficiaries of the IOTA participant's participation in the IOTA Model by, at a minimum, prominently displaying informational materials in offices or facilities where beneficiaries receive care. Additionally, IOTA participants would be subject to the proposed Standard Provisions for Innovation Center Models regarding descriptive model materials and activities in section II. of this proposed rule. Start Printed Page 43522

C. Summary of Costs and Benefits

The IOTA Model aims to incentivize transplant hospitals to overcome system-level barriers to kidney transplantation. The chronic shortfall in kidney transplants results in poorer outcomes for patients and increases the burden on Medicare in terms of payments for dialysis and dialysis-based enrollment in the program. There is reasonable evidence that the savings to Medicare resulting from an incremental growth in transplantation would potentially exceed the payments projected under the model's proposed incentive structure.

II. Standard Provisions for Innovation Center Models

A. Introduction

Section 1115A of the Act authorizes the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (the “Innovation Center”) to test innovative payment and service delivery models expected to reduce Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP expenditures, while preserving or enhancing the quality of care furnished to such programs' beneficiaries. We have designed and tested both voluntary Innovation Center models—governed by participation agreements, cooperative agreements, and model-specific addenda to existing contracts with CMS—and mandatory Innovation Center models that are governed by regulations. Each voluntary and mandatory model features its own specific payment methodology, quality metrics, and certain other applicable policies, but each model also features numerous provisions of a similar or identical nature, including provisions regarding cooperation in model evaluation; monitoring and compliance; and beneficiary protections.

On September 29, 2020, we published in the Federal Register a final rule titled “Medicare Program; Specialty Care Models To Improve Quality of Care and Reduce Expenditures” (85 FR 61114) (hereinafter the “Specialty Care Models final rule”), in which we adopted General Provisions Related to Innovation Center models at 42 CFR part 512 subpart A that apply to the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) Model and the Radiation Oncology (RO) Model.[8] The Specialty Care Models final rule codified general provisions regarding beneficiary protections, cooperation in model evaluation and monitoring, audits and record retention, rights in data and intellectual property, monitoring and compliance, remedial action, model termination by CMS, limitations on review, and bankruptcy and other notifications. These general provisions were adopted only for the ETC and RO Models (and, in practice, applied only to the ETC Model). However, we now believe the general provisions should apply to Innovation Center models more broadly. As we note, the Innovation Center models share numerous similar provisions, and codifying the general provisions into law to expand their applicability across models, except where otherwise explicitly specified in a model's governing documentation, would, we believe, promote transparency, efficiency, clarity, and ensure consistency across models to the extent appropriate, while avoiding the need to restate the provisions in each model's governing documentation.

We also propose a new provision pertaining to the reconsideration review process that would apply to Innovation Center models that waive the appeals processes provided under section 1869 of the Act.

B. General Provisions Codified in the Code of Federal Regulations That Would Apply to Innovation Center Models

Each Innovation Center model features many unique aspects that must be memorialized in its governing documentation, but each model also includes certain provisions that are common to most or all models. We believe that codifying these common provisions would facilitate their uniform application across models (except where the governing documentation for a particular model dictates otherwise) and promote program efficiency and consistency that would benefit CMS' program administration and model participants.

As such, we propose to expand the applicability of the 42 CFR part 512 subpart A “General Provisions Related to Innovation Center Models” to all Innovation Center models whose first performance periods begin on or after January 1, 2025, unless otherwise specified in the models' governing documentation, and also to any Innovation Center models whose first performance periods begin prior to January 1, 2025 if incorporated by reference into the models' governing documentation. To accomplish this, we propose that the provisions codified at 42 CFR part 512 subpart A for the ETC and RO Models, including those with respect to definitions, beneficiary protections, cooperation in model evaluation and monitoring, audits and record retention, rights in data and intellectual property, monitoring and compliance, remedial action, Innovation Center model termination by CMS, and limitations on review, would be designated as the newly defined “standard provisions for Innovation Center models” and would apply to all Innovation Center models as described Start Printed Page 43523 above. We propose specific revisions that would be necessary to expand the scope of several of the current general provisions, but otherwise propose that the general provisions (which would be referred to as the “standard provisions for Innovation Center models”) would not change. In particular, we propose that the substance of the following provisions would not change, except that they would apply to all Innovation Center Models as opposed to just the ETC and RO Models: § 512.120 Beneficiary protections; § 512.130 Cooperation in model evaluation and monitoring; § 512.135 Audits and record retention; § 512.140 Rights in data and intellectual property: § 512.150 Monitoring and compliance; § 512.160 Remedial action; § 512.165 Innovation center model termination by CMS; § 512.170 Limitations on review; and § 512.180 Miscellaneous provisions on bankruptcy and other notifications.

C. Proposed Revisions to the Titles, Basis and Scope Provision, and Effective Date

We propose to amend the title of part 512 to read “Standard Provisions for Innovation Center Models and Specific Provisions for the Radiation Oncology Model and the End Stage Renal Disease Model” so that it more closely aligns with the other changes proposed herein and to ensure that the title indicates that part 512 includes both standard provisions for Innovation Center models and specific provisions for the RO and ETC Models. We also propose to amend the title of subpart A to read “Standard Provisions for Innovation Center Models” to use the term we propose to define the provisions codified at 42 CFR part 512 subpart A.

Additionally, we propose to amend § 512.100(a) and (b) so that the standard provisions would take effect on January 1, 2025, and would apply to each Innovation Center model where that model's first performance period begins on or after January 1, 2025, unless the model's governing documentation indicates otherwise, as well as any Innovation Center model that begins testing its first performance period prior to January 1, 2025, if the model's governing documentation incorporates the provisions by reference in whole or in part. We propose to determine on a case-by-case basis, based on each model's unique features and design, whether the standard provisions would apply to a particular model, or whether we would specify alternate terms in the model's governing documentation.

We believe that these standard provisions are necessary for the testing of the IOTA model, regardless of whether they are finalized as proposed for all Innovation Center models. As such, as an alternative to the previous proposal, we would propose making these standard provisions for Innovation Center models applicable to, and effective for, the IOTA Model beginning on January 1, 2025, absent extending the standard provisions to all Innovation Center models. Under such an alternative, the general provisions in the Specialty Care Models final rule would also still be applicable to the ETC Model and the RO Model.

These proposed standard provisions would not, except as specifically noted in this section II. of this proposed rule, affect the applicability of other provisions affecting providers and suppliers under Medicare fee-for-service (FFS).

We invite public comment on these proposed changes.

D. Provisions Revising Certain Definitions

We propose to amend the definition of “Innovation Center model” at 42 CFR 512.110 by replacing the specific references to the RO and ETC Models with a definition consistent with section 1115A of the Act and intended to encompass all Innovation Center models. We propose to amend the definition for “Innovation Center model” to read as follows: “an innovative payment and service delivery model tested under the authority of section 1115A(b) of the Act, including a model expansion under section 1115A(c) of the Act.”

We propose to add a new definition of the term “governing documentation” at § 512.110 to mean, “the applicable Federal regulations, and the model-specific participation agreement, cooperative agreement, and any addendum to an existing contract with CMS, that collectively specify the terms of the Innovation Center model.” We propose to add a new definition, “standard provisions for Innovation Center models,” at § 512.110 to mean, “the provisions codified in 42 CFR 512 Subpart A.” We propose to add a new definition, “performance period,” at § 512.110 to mean, “the period of time during which an Innovation Center model is tested and model participants are held accountable for cost and quality of care; the performance period for each Innovation Center model is specified in the governing documentation.”

Further, we propose to amend the definitions of “Innovation Center model activities,” “model beneficiary,” and “model participant” to pertain to all “Innovation Center models,” as we propose to define that term, instead of just the models previously implemented under part 512. As such, we propose to define “Innovation Center model activities” to mean “any activities affecting the care of model beneficiaries related to the test of the Innovation Center model.” We propose to define “model beneficiary” to mean “a beneficiary attributed to a model participant or otherwise included in an Innovation Center model.” We propose to define “model participant” to mean “an individual or entity that is identified as a participant in the Innovation Center model.”

We invite public comment on these proposed changes to the definitions of “Innovation Center model,” “Innovation Center model activities,” “model beneficiary,” and “model participant” and the proposed definitions of “governing documentation,” “standard provisions for Innovation Center models,” and “performance period.”

E. Proposed Reconsideration Review Process

We propose to add a new § 512.190 to part 512 subpart A to codify a reconsideration review process, based on processes implemented under current Innovation Center models. The process would enable model participants to contest determinations made by CMS in certain Innovation Center models, where model participants would not otherwise have a means to dispute determinations made by CMS. We propose at § 512.190(a)(1) that such a reconsideration process would apply only to Innovation Center models that waive section 1869 of the Act, which governs determinations and appeals in Medicare, or where section 1869 would not apply because model participants are not Medicare-enrolled. We propose at § 512.190(a)(2) that only model participants may utilize the dispute resolution process, unless the governing documentation for the Innovation Center model states otherwise. Such limitations with respect to such models are, we believe, appropriate, because with respect to such models, model participants do not have another means to dispute determinations made by CMS. We propose to codify a reconsideration review process in regulation in order to have a transparent and consistent method of reconsideration for model participants participating in models that do not utilize the standard reconsideration process outlined in section 1869 of the Act.

This proposed reconsideration review process would be utilized where a model-specific determination has been made and the affected model participant Start Printed Page 43524 disagrees with, and wishes to challenge, that determination. Each Innovation Center model features a unique payment and service delivery model, and, as such, requires its own model-specific determination process. Each Innovation Center model's governing documentation details the model-specific determinations made by CMS, which may include, but are not limited to, model-specific payments, beneficiary attribution, and determinations regarding remedial actions. Each Innovation Center model's governing documentation also includes specific details about when a determination is final and may be disputed through the model's reconsideration review processes.

We propose at § 512.190(b) that model participants may request reconsideration of a determination made by CMS in accordance with an Innovation Center model's governing documentation only if such reconsideration is not precluded by section 1115A(d)(2) of the Act, part 512 subpart A, or the model's governing documentation. A model participant may challenge, by requesting review by a CMS reconsideration official, those final determinations made by CMS that are not precluded from administrative or judicial review. We propose at § 512.190(b)(i) that the CMS reconsideration official would be someone who is authorized to receive such requests and was not involved in the initial determination issued by CMS or, if applicable, the timely error notice review process. We propose at § 512.190(b)(ii) that the reconsideration review request would be required to include a copy of CMS's initial determination and contain a detailed written explanation of the basis for the dispute, including supporting documentation. We propose at § 512.190(b)(iii) that the request for reconsideration would have to be made within 30 days of the date of CMS' initial determination for which reconsideration is being requested via email to an address as specified by CMS in the governing documentation. At § 512.190(b)(2), we propose that requests that do not meet the requirements of paragraph (b)(1) would be denied.

We propose at § 512.190(b)(3) that the reconsideration official would send a written acknowledgement to CMS and to the model participant requesting reconsideration within 10 business days of receiving the reconsideration request. The acknowledgement would set forth the review procedures and a schedule that would permit each party an opportunity to submit position papers and documentation in support of its position for consideration by the reconsideration official.

We propose to codify at § 512.190(b)(4) that, to access the reconsideration process for a determination concerning a model-specific payment where the Innovation Center model's governing documentation specifies an initial timely error notice process, the model participant must first satisfy those requirements before submitting a reconsideration request under this process. Should a model participant fail to timely submit an error notice with respect to a particular model-specific payment, we propose that the reconsideration review process would not be available to the model participant with regard to that model-specific payment.

We propose to codify standards for reconsideration at § 512.190(c). First, during the course of the reconsideration, we propose that both CMS and the party requesting the reconsideration must continue to fulfill all responsibilities and obligations under the governing documentation during the course of any dispute arising under the governing documentation. Second, the reconsideration would consist of a review of documentation timely submitted to the reconsideration official and in accordance with the standards specified by the reconsideration official in the acknowledgement at § 512.190(b)(3). Finally, we propose that the model participant would bear the burden of proof to demonstrate with clear and convincing evidence to the reconsideration official that the determination made by CMS was inconsistent with the terms of the governing documentation.

We propose to codify at § 512.190(d) that the reconsideration determination would be an on-the-record review. By this, we mean a review that would be conducted by a CMS reconsideration official who is a designee of CMS who is authorized to receive such requests under proposed § 512.190(b)(1)(i), of the position papers and supporting documentation that are timely submitted and in accordance with the schedule specified under proposed § 512.190(b)(3)(ii) and that meet the standards of submission under proposed § 512.190(b)(1) as well as any documents and data timely submitted to CMS by the model participant in the required format before CMS made the initial determination that is the subject of the reconsideration request. We propose at § 512.190(d)(2) that the reconsideration official would issue to the parties a written reconsideration determination. Absent unusual circumstances, in which the reconsideration official would reserve the right to an extension upon written notice to the model participant, the reconsideration determination would be issued within 60 days of CMS's receipt of the timely filed position papers and supporting documentation in accordance with the schedule specified under proposed § 512.190(b)(3)(ii). Under proposed § 512.190(d)(3), the determination made by the CMS reconsideration official would be final and binding 30 days after its issuance, unless the model participant or CMS were to timely request review of the reconsideration determination by the CMS Administrator in accordance with §§ 512.190(e)(1) and (2).

We propose to codify at § 512.190(e) a process for the CMS Administrator to review reconsideration determinations made under § 512.190(d). We propose that either the model participant or CMS may request that the CMS Administrator review the reconsideration determination. The request to the CMS Administrator would have to be made via email, within 30 days of the reconsideration determination, to an email address specified by CMS. The request would have to include a copy of the reconsideration determination, as well as a detailed written explanation of why the model participant or CMS disagrees with the reconsideration determination. The CMS Administrator would promptly send the parties a written acknowledgement of receipt of the request for review. The CMS Administrator would send the parties notice of whether the request for review was granted or denied. If the request for review is granted, the notice would include the review procedures and a schedule that would permit each party to submit a brief in support of the party's positions for consideration by the CMS Administrator. If the request for review is denied, the reconsideration determination would be final and binding as of the date of denial of the request for review by the CMS Administrator. If the request for review by the CMS Administrator is granted, the record for review would consist solely of timely submitted briefs and evidence contained in the record of the proceedings before the reconsideration official and evidence as set forth in the documents and data described in proposed § 512.190(d)(1)(ii); the CMS Administrator would not consider evidence other than information set forth in the documents and data described in proposed § 512.190(d)(1)(ii). The CMS Start Printed Page 43525 Administrator would review the record and issue to the parties a written determination that would be final and binding as of the date the written determination is sent.

We invite public comment on the proposed reconsideration review process for Innovation Center models.

III. Proposed Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Model

A. Introduction

In this proposed rule, we are proposing to test the IOTA Model, a new mandatory Medicare alternative payment model under the authority of the Innovation Center, that would begin on January 1, 2025, and end on December 31, 2030. The IOTA Model would test whether using performance-based incentive payments in the form of upside risk payments and downside risk payments to and from select transplant hospitals increases the number of kidney transplants furnished to patients with ESRD, thereby reducing Medicare expenditures while preserving or enhancing quality of care.

The goal of the proposed performance-based payments is: to increase the number of kidney transplants furnished to ESRD patients placed on a kidney transplant hospital's waitlist; encourage investments in value-based care and quality improvement activities, particularly those that promote an equitable kidney transplant process prior to, during, and post transplantation for all patients; encourage better use of the current supply of deceased donor organs and greater provider and community collaborations to address medical and non-medical needs of patients; and increased awareness, education, and support for living donations. The IOTA Model payment structure would also promote IOTA participant accountability by linking performance-based payments to quality. We theorize that increasing the number of kidney transplants furnished to ESRD patients on the participating hospitals' waitlists would reduce Medicare expenditures by reducing dialysis expenditures and avoidable health care service utilization and would improve the quality of life for patients with ESRD.

As discussed in section III.B of this proposed rule, studies show that kidney transplant hospitals are underutilizing donor kidneys and have become more conservative in accepting organs for transplantation, with notable variation by region and across transplant hospitals.[9] The IOTA Model aims to address these access and equity problems through financial incentives that reward IOTA participants that improve their kidney organ offer acceptance rate ratios over time or hold them financially accountable for not doing so. The IOTA Model's proposed payment structure would include upside or downside performance-based incentive payments (“upside risk payment” or “downside risk payment”) for kidney transplant hospitals selected to participate in the IOTA Model (“IOTA participant”), with these payments being tied to performance on achievement, efficiency, and quality domains.

The achievement domain would assess the number of kidney transplants performed relative to a participant-specific target, with performance on this domain being worth up to 60 points. The efficiency domain would assess kidney organ offer acceptance rate ratios relative to a national rate for all kidney transplant hospitals, including those not selected to participate in the model, with performance on this domain being worth up to 20 points. The quality domain would assess performance based on post-transplant outcomes at one-year after transplant and a proposed set of quality measures, with performance on this domain being worth up to 20 points. The achievement domain would be weighted more heavily than the other two domains because increasing the number of transplants is a key goal of the model and would be a primary factor in determining the amount of the performance-based payment.

The final performance score for each IOTA participant would be the sum of the points earned across the achievement domain, efficiency domain, and quality domain. The final performance score would determine whether an upside risk payment or downward risk payment would be owed and the amount of such payment. Specifically:

- For PY 1, if an IOTA participant has a final performance score between 60 and 100 points, it would qualify for the upside risk payment in accordance with the proposed calculation methodology described in section III.C.6.c(a) of this proposed rule (final performance score minus 60, then divided by 60, then multiplied by $8,000, then multiplied by the number of kidney transplants furnished by the IOTA participant to beneficiaries with Medicare as a primary or secondary payer during the PY).

- For PY 1, if an IOTA participant has a final performance score below 60, it would fall into a neutral zone where no upside risk payment and no downside risk payment would apply.

- For PY 2 and each subsequent PY (PYs 2-6) if an IOTA participant achieves a final performance score of 41 to 59 points, it would fall into a neutral zone where no upside risk payment and no downside risk payment would apply.

- For PY 2 and each subsequent PY, if an IOTA participant achieves a final performance score of 40 points or below, it would qualify for the downside risk payment in accordance with the proposed calculation methodology described in section III.C.6.c.(b). of this proposed rule (final performance score minus 40, then divided by 40, then multiplied by −$2,000, then multiplied by the number of kidney transplants furnished by the IOTA participant to beneficiaries with Medicare as a primary or secondary payer during the PY).

We recognize the complexity of the transplant ecosystem, which requires coordination between transplant hospitals, other health care providers, organ procurement organizations (OPOs), patients, potential donors, and their families. The proposed IOTA Model does not prescribe or require specific processes or policy approaches that each selected IOTA participant must implement for purposes of the model test.

We believe the IOTA Model would complement other efforts in relation to the transplant ecosystem to enhance health and safety outcomes, increase transparency, increase the number of transplants, and reduce disparities. We also believe that the proposed payment methodology would act in concert with measures that are currently under development by HRSA to increase the numbers of both deceased and living donor organ transplants.

This proposed model falls within a larger framework of activities initiated by the Federal Government during the past several years and planned for the upcoming year to enhance the donation, procurement, and transplantation of solid organs. This Federal collaborative, called the Organ Transplantation Affinity Group (OTAG), is a coordinated group working together to strengthen accountability, equity, and performance in organ donation, procurement, and transplantation.[10]

Start Printed Page 43526B. Background

A review of the literature on kidney transplantation shows that the increasing numbers of kidney transplants is unable to keep pace with the increasing need for organs.[11] While more people die waiting for a kidney transplant, the short- and long-term outcomes of patients who undergo kidney transplantation have improved, despite both recipients and donors increasing in age and adverse health conditions.[12] Recent studies show that transplant hospitals have become more conservative in accepting organs for transplantation when offered for specific patients, avoiding the use of less-than-ideal organs on account of perceived risk.[13] Wide variation among geographic regions and transplant hospitals in rates of kidney transplantation, along with access and equity issues, raises the need to hold kidney transplant hospitals accountable for performance.[14] The IOTA Model proposes a two-sided performance-based payment structure that rewards IOTA participants for high performance in the achievement, efficiency, and quality domains, and imposes financial accountability on IOTA participants that perform poorly on those domains. We propose the IOTA Model as a complement to wider efforts aimed at transplant ecosystem performance and equity improvements. Ultimately, we seek a set of interventions that focus on ESRD patients in need of a kidney transplant. In this section of the proposed rule, we summarize the transplant ecosystem and HHS oversight within CMS and HRSA related to kidney transplantation, highlight related initiatives and priorities nationally, and outline our rationale for the proposed IOTA Model informed by literature, data, and studies.

1. The Transplant Ecosystem

Kidney transplantation occurs within an overall organ donation and transplantation system (also known and referred to as the transplant ecosystem) that comprises a vast network of institutions dedicated to ensuring that patients are evaluated and, if appropriate, placed onto the organ transplant waitlist, and that those on the organ transplant waitlist receive lifesaving organ transplants. Transplantation of livers, hearts, lungs, and other organs is also well established within the U.S. health care system. The transplant ecosystem includes the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN); Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs); transplant hospitals and providers; histocompatibility laboratories that provide blood, tissue, and antibody testing for the organ matching process; and patients, including ESRD patients in need of a transplant, their families, and caregivers.[15] For kidney transplantation, it also includes ESRD facilities, commonly known as dialysis facilities.

The National Organ Transplant Act of 1984, referred to herein as NOTA, established the OPTN, with HHS oversight, to manage and operate the national organ transplantation system (42 U.S.C. 274). The OPTN coordinates the nation's organ procurement, distribution, and transplantation systems. The OPTN is a network of clinical experts, patients, donor families, and community stakeholders who work collectively to develop, implement, and monitor organ allocation policy and performance of the organ transplant ecosystem.

Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs) are non-profit organizations operating under contract with the Federal Government that are charged, under section 371(b) of the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act, 42 U.S.C. 273(b)) with activities including, but not limited to, identifying potential organ donors, providing for the acquisition and preservation of donated organs, the equitable allocation of donated organs, and the transportation of donated organs to transplant hospitals. Section 371(b) of the Public Health Services Act requires that an OPO must have a defined service area, a concept that is defined at 42 CFR part 486 subpart G as the Donation Service Area (DSA). Section 1138(b) of the Act states that the Secretary may not designate more than one OPO to serve each DSA. There are currently 56 OPOs that serve the United States and Puerto Rico.

Section 1138(b) of the Act lays out the requirements that an OPO must meet to have its costs reimbursed by the Secretary. CMS sets out the components of allowable Medicare organ acquisition costs at 42 CFR 413.402(b). Allowable organ acquisition costs are those costs incurred in the acquisition of organs intended for transplant, and include, but are not limited to: costs associated with special care services, the surgeon's fee for excising the deceased donor organ from the donor patient (limited to $1,250 for kidneys), operating room and other inpatient ancillary services provided to the living or deceased donor, organ preservation and perfusion costs, donor and beneficiary evaluation, and living donor complications. OPOs and transplant hospitals may incur organ acquisition costs and include these and some additional administrative and general costs on the Medicare cost report.

The CMS conditions for coverage for OPOs at 42 CFR 486.322 require an OPO to have written agreements with 95 percent of the Medicare and Medicaid certified hospitals and critical access hospitals in its DSA that have a ventilator and an operating room and have not been granted a waiver to work with another OPO. These hospitals, known as donor hospitals, are required by the CMS conditions of participation for hospitals at 42 CFR 482.45 to have an agreement with an OPO under which the donor hospital must notify the OPO of patients who are expected to die imminently and of patients who have died in the hospital. (Under the hospital conditions of participation, such an agreement is required of all hospitals that participate in Medicare.) Also, under the hospital conditions of participation, donor hospitals are responsible for informing donor patient families of the option to donate organs, tissues, and eyes, or to decline to donate; and to work collaboratively with the OPO to educate hospital staff on donation, improve its identification of potential donors, and work with the OPO to manage the potential donor patient while testing and placement of the potential donor organ occurs.

At 42 CFR 482.70, CMS defines a transplant hospital as “a hospital that furnishes organ transplants and other medical and surgical specialty services Start Printed Page 43527 required for the care of transplant patients,” and a transplant program as “an organ-specific transplant program within a transplant hospital,” as so defined. In accordance with 42 CFR 482.98, a transplant program must have a primary transplant surgeon and a transplant physician with the appropriate training and experience to provide transplantation services, who are immediately available to provide transplantation services when an organ is offered for transplantation. The transplant surgeon is responsible for providing surgical services related to transplantation, and the transplant physician is responsible for providing and coordinating transplantation care.

In accordance with CMS' Conditions for Coverage (CfC) for ESRD Facilities at 42 CFR part 494, ESRD facilities are charged with delivering safe and adequate dialysis to ESRD patients, and, among other requirements, informing patients of their treatment modalities, including dialysis and kidney transplantation. The CfCs require ESRD facilities to conduct a patient assessment that includes evaluation of suitability for referral for transplantation, based on criteria developed by the prospective transplantation center and its surgeon(s). General nephrologists refer patients for evaluation for kidney transplants.[16] Candidates for kidney transplant undergo a rigorous evaluation by a transplant program prior to placement on a waitlist, involving evaluation by a multidisciplinary team for conditions pertaining to the potential success of the transplant, the possibility of recurrence, and surgical issues including frailty, obesity, diabetes and other causes of ESRD, infections, malignancies, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, peripheral arterial disease, neurologic disease, hematologic conditions, and gastrointestinal and liver disease and an immunological assessment; a psychosocial assessment; assessment of adherence behaviors; and tobacco counseling.[17]

Once placed on the waitlist, potential recipients must maintain active status to be eligible to receive a deceased donor transplant.[18] An individual may receive a status of `inactive' if they are missing lab results, contact information, or any of the other requirements that would be necessary for them to receive an organ transplant if offered. An individual may only receive an organ offer if they have a status of `active'.[19] Each transplant hospital has its own waitlist, and patients can attempt to be placed on multiple waitlists; OPTN maintains a national transplant waiting list that encompasses the waitlists for all kidney transplant hospitals.[20 21] Individuals already on dialysis continue to receive regular dialysis treatments while waiting for an organ to become available. After surgery, a transplant nephrologist manages the possible outcomes of organ rejection and infection, and other medical complications.[22]

2. HHS Oversight and Priorities

HRSA, which oversees the OPTN, and CMS play a vital role in protecting the health and safety of Americans as they engage with the U.S. health care system.[23] The OPTN operates a complex network of computerized interactions whereby specific deceased donor organs get matched to individual patients on the national transplant waiting list. The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), operated under contract with HRSA, is responsible for providing statistical and analytic support to the OPTN. Section 373 of the PHS Act requires the operation of the SRTR to support ongoing evaluation of the scientific and clinical status of solid organ transplantation.[24]

CMS oversees and evaluates OPO performance. OPOs must meet performance measures and participate in, and abide by certain rules of, the OPTN.[25] The PHS Act requires the Secretary to establish outcome and process performance measures to recertify OPOs (Part H section 371; 42 U.S.C. 273). CMS has promulgated the OPO CfCs at 42 CFR part 486 subpart G.

Additionally, the OPTN Bylaws specify that OPOs whose observed organ yield rates fall below the expected rates by more than a specified threshold would be reviewed by the OPTN Membership Professional Standards Committee (MPSC).[26] CMS also conducts oversight of transplant programs, located within transplant hospitals, which must abide by both the hospital and the transplant program conditions of participation (CoPs). CMS contracts with quality improvement entities such as the ESRD Networks and Quality Improvement Organizations to provide technical support to providers and patients seeking improvements in the transplant ecosystem.

Medicare covers certain transplant-related services when provided at a Medicare-approved facility. Medicare Part A covers the costs associated with a Medicare kidney transplant procedure received in a Medicare-certified hospital and any additional inpatient hospital care needed following the procedure, and organ acquisition costs including kidney registry fees and laboratory tests associated with the evaluation of a Medicare transplant candidate. The evaluation or preparation of a living donor, the living donor's donation of the kidney, and postoperative recovery services directly related to the living donor's kidney donation are covered under Medicare. In addition, deductible and coinsurance requirements do not apply to living donors for services furnished to an individual in connection with the donation of a kidney for transplant surgery. Medicare Part B coverage includes the surgeon's fees for performing the kidney transplant procedure and perioperative care. Medicare Part B also covers physician services for the living kidney donor without regard to whether the service would otherwise be covered by Start Printed Page 43528 Medicare. Part A and Part B share responsibility for covering blood, including packed red blood cells, blood components and the cost of processing and receiving blood.

Medicare Part B covers immunosuppressive drugs following an organ transplant for which payment is made under Title XVIII. Immunosuppressive drugs following an organ transplant are covered by Part D when an individual did not have Part A at the time of the transplant. Beneficiaries who have Medicare due to ESRD alone lose Medicare coverage 36 months following a successful kidney transplant. Section 402(a) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) of 2021 added section 1836(b) of the Act to provide coverage for immunosuppressive drugs beginning January 1, 2023, for eligible individuals whose eligibility for Medicare based on ESRD ends by reason of section 226A(b)(2) of the Act for those three-years post kidney transplant. Under section 1833 of the Act, the amounts paid by Medicare for immunosuppressive drugs are equal to 80 percent of the applicable payment amount; beneficiaries are thus subject to a 20 percent coinsurance for immunosuppressive drugs covered by both Part B and the Medicare Part B Immunosuppressive Drug Benefit (Part B-ID).

3. Federal Government Initiatives To Enhance Organ Transplantation

a. CMS Regulatory Initiatives To Enhance Organ Transplantation

On September 30, 2019, we published the final rule, “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Regulatory Provisions To Promote Program Efficiency, Transparency, and Burden Reduction; Fire Safety Requirements for Certain Dialysis Facilities; Hospital and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Changes To Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care” (84 FR 51732). The rulemaking, in part, aimed to address the concern that too many organs are being discarded that could be transplanted successfully, including hearts, lungs, livers, and kidneys. This rule implemented changes to the transplant program regulations, eliminating requirements for re-approval of transplant programs pertaining to data submission, clinical experience, and outcomes. We believed that the removal of these requirements aligned with our goal of increasing access to kidney transplants by increasing the utilization of organs from deceased donors and reducing the organ discard rate (84 FR 51749). We sought improved organ procurement, greater organ utilization, and reduction of burden for transplant hospitals, while still maintaining the importance of safety in the transplant process.

On December 2, 2020, we issued a final rule titled, “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Organ Procurement Organizations Conditions for Coverage: Revisions to the Outcome Measure Requirements for Organ Procurement Organizations” (85 FR 77898), which revised the OPO CfCs by replacing the previous outcome measures with new transparent, reliable, and objective outcome measures. In modifying the metrics used for assessing OPO performance, we sought to promote greater utilization of organs that might not otherwise be recovered or used due to perceived organ quality.[27]

While these regulatory changes recently went into effect with the goal of improving the performance of transplant hospitals and OPOs and to promote the procuring of organs and delivering them to prospective transplant recipients, we acknowledged the need for improvements in health, safety, and outcomes across the transplant ecosystem, including in transplant programs, OPOs, and ESRD facilities.[28 29] In particular, we recognize that further action must be taken to address disparities and inequities observed across transplant hospitals.

We published a request for information in the Federal Register on December 3, 2021, titled “Request for Information: Health and Safety Requirements for Transplant Programs, Organ Procurement Organizations, and End-Stage Renal Facilities” (86 FR 68594) (hereafter known as the “Transplant Ecosystem RFI”). This RFI solicited public comments on potential changes to the requirements that transplant programs, OPOs, and ESRD facilities must meet to participate in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Specifically, we solicited public comments on ways to:

- Continue to improve systems of care for all patients in need of a transplant;

- Increase the number of organs available for transplant for all solid organ types;

- Encourage the use of dialysis in alternate settings or modalities over in-center hemodialysis where clinically appropriate and advantageous;

- Ensure that the CMS and HHS policies appropriately incentivize the creation and use of future new treatments and technologies; and

- Harmonize requirements across government agencies to facilitate these objectives and improve quality across the organ donation and transplantation ecosystem.

We also solicited information related to opportunities, inefficiencies, and inequities in the transplant ecosystem and what can be done to ensure all segments of our healthcare systems are invested and accountable in ensuring improvements to organ donation and transplantation rates (86 FR 68596). The Transplant Ecosystem RFI focused on questions in the areas of transplantation, kidney health and ESRD facilities, and OPOs. For transplant programs, specific topics included transplant program CoPs, patient rights, and equity in organ transplantation and organ donation (86 FR 68596). For kidney health and ESRD facilities, topics included maintaining and improving health of patients, ways to identify those at risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD), improving detection rates of CKD, and ways to close the CKD detection, education, and care health equity gap (86 FR 68599). Other topics included home dialysis, dialysis in alternative settings such as nursing homes and mobile dialysis, and alternate models of care (86 FR 68600). For OPOs, specific topics included assessment and recertification, organ transport and tracking, the donor referral process, organ recovery centers, organ discards, donation after cardiac death, tissue banks, organs for research, and vascular composite organs. (86 FR 68601 through 68606)

The Transplant Ecosystem RFI followed three executive orders addressing health equity that were issued by President Biden on January 20 and January 21, 2021—

- Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government (E.O. 13985, 86 FR 7009, January 20, 2021); Start Printed Page 43529

- Executive Order on Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation (E.O. 13988, 86 FR 7023, January 25, 2021); and

- Executive Order on Ensuring an Equitable Pandemic Response and Recovery (E.O. 13995, 86 FR 7193, January 26, 2021).

The RFI was among several issued by CMS in 2021 to request public comment on ways to advance health equity and reduce disparities in our policies and programs.

CMS's regulatory initiatives since 2018 pertaining to organ donation and transplantation have included final rules modifying CoPs and CfCs for transplant programs (84 FR 51732) and OPOs (85 FR 77898), respectively, and our recent RFI on transplant program CoPs, OPO CfCs, and the ESRD facility CfCs (86 FR 68594). These regulations and RFIs have sought to foster greater health and safety for patients, greater transparency for all patients, increases in organ donation and transplantation, and reduced disparities in organ donation and transplantation. Through these regulations, we are working to attain these goals by designing and implementing policies that improve health for all people affected by the transplant ecosystem.

b. CMS Innovation Center Payment Models

The Innovation Center is currently pursuing complementary alternative payment model tests—the ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) Model and the Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model—aimed at enhancing kidney transplantation and improving health-related outcomes for patients with late-stage CKD and ESRD, thereby reducing costs to the Medicare program. The impetus for the ETC and KCC Models originated with evaluation findings for the earlier Comprehensive ESRD Care (CEC) Model, which ran from October 2015 through March 2021, that showed large dialysis organizations achieving positive clinical and financial outcomes relating to services to Medicare beneficiaries receiving dialysis, though the CEC Model did not achieve net savings to Medicare.[30] The CEC Model focused on patients being treated in ESRD facilities, with no explicit incentives to encourage increases in kidney transplantation.

The ETC and KCC Models have engaged a broader range of health care providers beyond ESRD facilities, including nephrology professionals and transplant providers, and address transplantation. Each model includes direct financial incentives for increasing the number of kidney transplants.

The ETC Model, which began January 1, 2021, and which is scheduled to end on June 30, 2027, is a mandatory model that tests whether greater use of home dialysis and kidney transplantation for Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD reduces Medicare expenditures while preserving or enhancing the quality of care furnished to those beneficiaries. We established requirements for the ETC Model in the Medicare Program; Specialty Care Models to Improve Quality of Care and Reduce Expenditures final rule (85 FR 61114 through 61381). These requirements are codified at 42 CFR subpart C. The ETC Model tests the effects of certain Medicare payment adjustments to participating ESRD facilities and Managing Clinicians (clinicians who manage ESRD beneficiaries and bill the Monthly Capitation Payment (MCP)). The payment adjustments are designed to encourage greater utilization of home dialysis and kidney transplantation, support beneficiary modality choice, reduce Medicare expenditures, and preserve or enhance quality of care. Under the ETC Model, CMS makes upward adjustments to certain payments under the ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS) to certain dialysis facilities on home dialysis claims, and upward adjustments to the MCP paid to certain Managing Clinicians on home dialysis-related claims (85 FR 61117). In addition, CMS makes upward and downward adjustments to PPS payments to participating ESRD facilities and to the MCP paid to participating Managing Clinicians based on the Participant's home dialysis rate and transplant waitlisting and living donor transplant rate (85 FR 61117). The ETC Model's objectives, as described in the final rule, include supporting paired donations and donor chains, and reducing the likelihood that potentially viable organs are discarded (85 FR 61128). The ETC Model was updated by the final rule dated November 8, 2021, titled “Medicare Program; End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System, Payment for Renal Dialysis Services Furnished to Individuals With Acute Kidney Injury, End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program, and End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices Model” and the final rule dated November 7, 2022, titled “Medicare Program; End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System, Payment for Renal Dialysis Services Furnished to Individuals With Acute Kidney Injury, End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program, and End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices Model” (87 FR 67136). We finalized further modifications to the ETC Model related to the availability of administrative review of an ETC Participant's targeted review request in the final rule issued on November 6, 2023, titled “Medicare Program; End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System, Payment for Renal Dialysis Services Furnished to Individuals With Acute Kidney Injury, End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program, and End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices Model” (88 FR 76345).

CMS is also operating the ETC Learning Collaborative, which is focused on increasing the availability of deceased donor organs for transplantation.[31] The ETC Learning Collaborative regularly convenes ETC Participants, transplant hospitals, OPOs, and large donor hospitals, with the goal of using learning and quality improvement techniques to systematically spread the best practices of the highest performing organizations. CMS is employing quality improvement approaches to improve performance by collecting and analyzing data to identify the highest performers, and to help others to test, adapt and spread the best practices of these high performers throughout the entire national organ recovery system (85 FR 61346).

The KCC Model, which began its performance period on January 1, 2022, and is scheduled to end on December 31, 2026, is a voluntary model that also builds upon the CEC Model structure to encourage health care providers to better manage the care for Medicare beneficiaries with CKD stages 4 and 5 and ESRD, delay the onset of dialysis, and incentivize kidney transplantation. Various entities are participating in the KCC Model, including nephrologists and nephrology practices, dialysis facilities, and other health care providers. The participating entities receive a bonus payment for each aligned beneficiary who receives a Start Printed Page 43530 kidney transplant, so long as the transplant remains successful over a certain time period. CMS plans to continue to evaluate the effectiveness of the ETC and KCC Models in achieving clinical goals, improving quality of care, and reducing Medicare costs.[32]