-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 61294

AGENCY:

Office of Head Start (OHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

This final rule modernizes the Head Start Program Performance Standards, last revised in 1998. In the Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, Congress instructed the Office of Head Start to update its performance standards and to ensure any such revisions to the standards do not eliminate or reduce quality, scope, or types of health, educational, parental involvement, nutritional, social, or other services programs provide. This rule responds to public comment, incorporates extensive findings from research and from consultation with experts, reflects best practices, lessons from program input and innovation, integrates recommendations from the Secretary's Advisory Committee Final Report on Head Start Research and Evaluation, and reflects the Obama Administration's deep commitment to improve the school readiness of young children. These performance standards will improve program quality, reduce burden on programs, and improve regulatory clarity and transparency. They provide a clear road map for current and prospective grantees to support high-quality Head Start services and to strengthen the outcomes of the children and families Head Start serves.

DATES:

Effective Date: Provisions of this final rule become effective November 7, 2016.

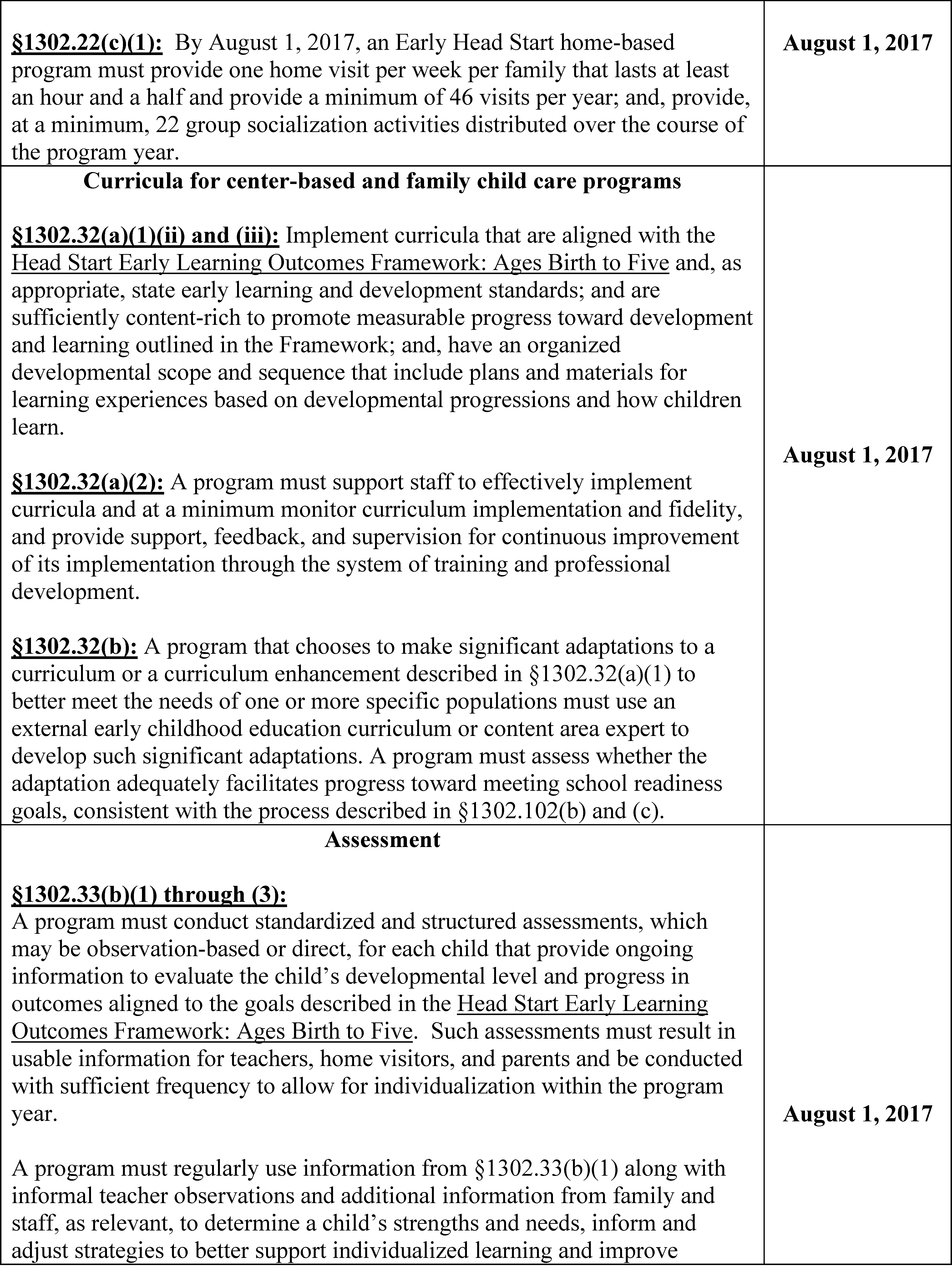

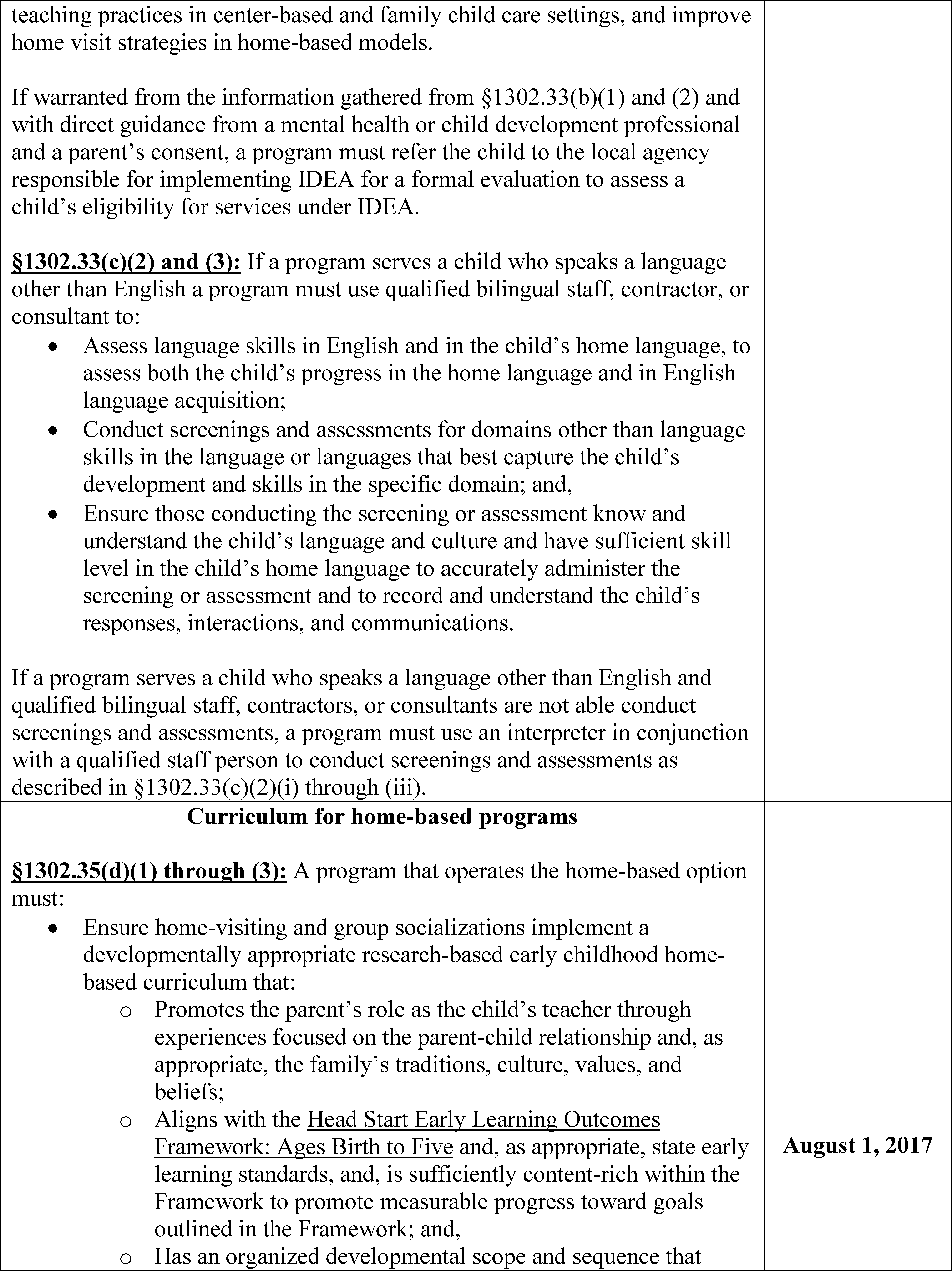

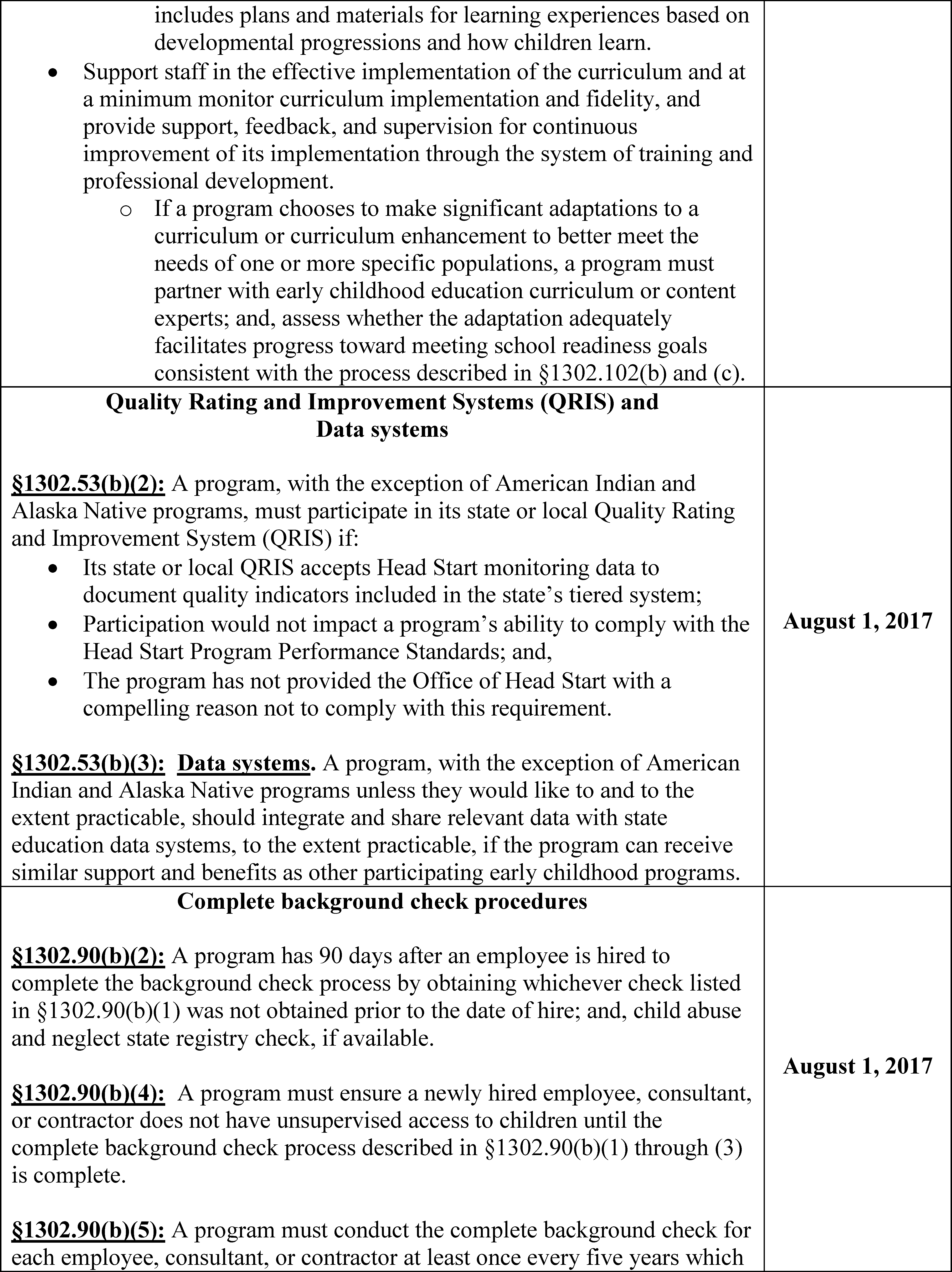

Compliance Date(s): To allow programs reasonable time to implement certain performance standards, we phase in compliance dates over several years after this final rule becomes effective. In the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION section below, we provide a table, Table 1: Compliance Table, which lists dates by which programs must implement specific standards.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Colleen Rathgeb, Division Director of Early Childhood Policy and Budget, Office of Early Childhood Development, at OHS_Final_Rule@acf.hhs.gov or (202) 401-1195 (not a toll free call). Deaf and hearing impaired individuals may call the Federal Dual Party Relay Service at 1-800-877-8339 between 8 a.m. and 7 p.m. Eastern Time.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

II. Tables

Table 1: Compliance Table

Table 2: Redesignation Table

III. Background

a. Statutory Authority

b. Purpose of This Rule

c. Rulemaking and Comment Processes

d. Overview of Major Changes From the NPRM

IV. Discussion of General Comments on the Final Rule

V. Discussion of Section by Section Comments on the Final Rule

a. Program Governance

b. Program Operations

1. Subpart A Eligibility, Recruitment, Selection, Enrollment and Attendance

2. Subpart B Program Structure

3. Subpart C Education and Child Development Program Services

4. Subpart D Health Program Services

5. Subpart E Family and Community Engagement Program Services

6. Subpart F Additional Services for Children With Disabilities

7. Subpart G Transition Services

8. Subpart H Services to Enrolled Pregnant Women

9. Subpart I Human Resources Management

10. Subpart J Program Management and Quality Improvement

c. Financial and Administrative Requirements

1. Subpart A Financial Requirements

2. Subpart B Administrative Requirements

3. Subpart C Protections for the Privacy of Child Records

4. Subpart D Delegation of Program Operations

5. Subpart E Facilities

6. Subpart F Transportation

d. Federal Administrative Procedures

1. Subpart A Monitoring, Suspension, Termination, Denial of Refunding, Reduction in Funding and Their Appeals

2. Subpart B Designation Renewal

3. Subpart C Selection of Grantees Through Competition

4. Subpart D Replacement of American Indian and Alaska Native Grantee

5. Subpart E Head Start Fellows Program

e. Definitions

VIII. Regulatory Process Matters

a. Regulatory Flexibility Act

b. Regulatory Planning and Review Executive Order 12866

1. Need for Regulatory Action: Increasing the Benefits to Society of Head Start

2. Cost and Savings Analysis

i. Structural Program Option Provisions

ii. Educator Quality Provisions

iii. Curriculum and Assessment Provisions

iv. Administrative/Managerial Provisions

3. Benefit Analysis

4. Accounting Statement

5. Distributional Effects

6. Regulatory Alternatives

c. Unfunded Mandates Reform Act

d. Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act of 1999

e. Federalism Assessment Executive Order 13132

f. Congressional Review

g. Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995

Tribal Consultation Statement

I. Executive Summary

Head Start currently provides comprehensive early learning services to more than 1 million children from birth to age five each year through more than 60,000 classes, home visitors, and family child care partners nationwide.[1] Since its inception in 1965, Head Start has been a leader in helping children from low-income families enter kindergarten more prepared to succeed in school and in life. Head Start is a central part of this Administration's effort to ensure all children have access to high-quality early learning opportunities and to eliminate the education achievement gap. This regulation is intended to improve the quality of Head Start services so that programs have a stronger impact on children's learning and development. It also is necessary to streamline and reorganize the regulatory structure to improve regulatory clarity and transparency so that existing grantees can more easily run a high-quality Head Start program and so that Head Start's operational requirements will be more transparent and seem less onerous to prospective grantees. In addition, this regulation is necessary to reduce the burden on local programs that can interfere with high-quality service delivery. We believe these regulatory changes will help ensure every child and family in Head Start receives high-quality services that will lead to greater success in school and in life.

In 2007, Congress mandated the Secretary to revise the program performance standards and update and raise the education standards.[2] Congress also prohibited elimination of, or any reduction in, the quality, scope, or types of services in the revisions.[3] Thus, these regulatory revisions are additionally intended to meet the statutory requirements Congress put forth in the bipartisan reauthorization of Head Start in 2007.

Start Printed Page 61295The Head Start Program Performance Standards are the foundation on which programs design and deliver comprehensive, high-quality individualized services to support the school readiness of children from low-income families. The first set of Head Start Program Performance Standards was published in the 1970s. Since then, they have been revised following subsequent Congressional reauthorizations and were last revised in 1998. The program performance standards set forth the requirements local grantees must meet to support the cognitive, social, emotional, and healthy development of children from birth to age five. They encompass requirements to provide education, health, mental health, nutrition, and family and community engagement services, as well as rules for local program governance and aspects of federal administration of the program.

This final rule builds upon extensive consultation with researchers, practitioners, recommendations from the Secretary's Advisory Committee Final Report on Head Start Research and Evaluation,[4] and other experts, public comment, as well as internal analysis of program data and years of program input. In addition, program monitoring has also provided invaluable experience regarding the strengths and weaknesses of the previous program performance standards. Moreover, research and practice in the field of early childhood education has expanded exponentially in the 15 years since the program performance standards governing service delivery were last revised, providing a multitude of new insights on how to support improved child outcomes.

The Secretary's Advisory Committee, which consisted of expert researchers and practitioners chartered to provide “recommendations for improving Head Start program effectiveness” concluded early education programs, including Head Start, are capable of reducing the achievement gap, but that Head Start is not reaching its potential.[5] As part of their work, the Committee provided recommendations for interpreting the results of both the Head Start Impact Study (HSIS),[6] a randomized control trial study of children in Head Start in 2002 and 2003 through third grade, and the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project (EHSREP),[7] which was initiated in 1996 and followed children who were eligible to participate in Early Head Start. The Committee concluded that these findings should be interpreted in the context of the larger body of research that demonstrates Head Start and Early Head Start “are improving family well-being and improving school readiness of children at or below the poverty line in the U.S. today.” [8] The Committee agreed the initial impact both Head Start and Early Head Start have demonstrated “are in line with the magnitude of findings from other scaled-up programs for infants and toddlers . . . and center-based programs for preschoolers . . .” but also acknowledged “larger impacts may be possible, e.g., by increasing dosage in [Early Head Start] and Head Start or improving instructional factors in Head Start.”[9] The Committee also addressed the finding that these impacts do not seem to persist into elementary school, stating the larger body of research on Head Start provides “evidence of long-term positive outcomes for those who participated in Head Start in terms of high school completion, avoidance of problem behaviors, avoidance of entry into the criminal justice system, too-early family formation, avoidance of special education, and workforce attachment.” Overall, the report determined a key factor for Head Start to realize its potential is “making quality and other improvements and optimizing dosage within Head Start [and Early Head Start].” The final rule aims to capitalize on the advancements in research, available data, program input, public comment, and these recommendations in order to accomplish the critical goal of helping Head Start reach its full potential so more children reach kindergarten ready to succeed.

This final rule reorganizes previous program performance standards to make it easier for grantees to implement them and for the public to understand the broad range of Head Start program services. Our previous program performance standards consisted of 1,400 provisions organized in 11 different sections that were amended in a partial or topical fashion over the past 40 years. This approach resulted in a somewhat opaque set of requirements that were unnecessarily challenging to interpret and overburdened grantees with process-laden rules.

This rule has four distinct sections: (1) Program Governance, which outlines the requirements imposed by the Head Start Act (the “Act”) on Governing Bodies and Policy Councils to ensure well-governed Head Start programs; (2) Program Operations, which outlines all of the operational requirements for serving children and families, from the universe of eligible children and the services they must be provided in education, health, and family and community engagement, to the way programs must use data to improve the services they provide; (3) Financial and Administrative Requirements, which lays out the federal requirements Head Start programs must adhere to because of overarching federal requirements or specific provisions imposed in the Act; and (4) Federal Administrative Procedures, which governs the procedures the responsible HHS official takes to determine the results of competition for all grantees, any actions against a grantee, whether a grantee needs to compete for renewed funding, and other transparency-related procedures required in the Act.

We also reorganized specific sections and streamlined provisions to make Head Start requirements easier to understand for all interested parties—grantees, potential grantees, other early education programs, and members of the general public. We reorganized subparts and their sections to eliminate redundancy, and we grouped together related requirements. Additionally, we systematically addressed the fact that many of our most critical provisions were buried in subparts that made them difficult to find and interpret, and did not reflect their centrality to the provision of high-quality services. For example, we created new subparts or sections to highlight and expand, where necessary, upon these important requirements.

We also streamlined requirements and minimized administrative burden on local programs. In total, we significantly reduced the number of regulatory requirements without compromising quality. We give programs greater flexibility to determine how best to Start Printed Page 61296achieve their goals and administer a high-quality Head Start program without reducing expectations for children and families. We anticipate these changes will help move Head Start away from a compliance-oriented culture to an outcomes-focused one. Furthermore, we believe this approach will support better collaboration with other programs and funding streams. We recognize that grantees deliver services through a variety of modalities including child care and state pre-kindergarten programs. Additionally, we removed other overly prescriptive requirements related to governing bodies, appeals, and audits.

We include several provisions to support local flexibility to meet community needs and to promote innovation and research. We give Head Start programs additional flexibility in the structural requirements of program models, such as group size and ratios. Further, we permit local variations for effective and innovative curriculum and professional development models, giving flexibility from some of these requirements if the Head Start program works with research experts and evaluates the effectiveness of their model. We also support local innovation through a process to waive individual eligibility verification requirements, which will allow better coordination with local early education programs without reducing quality. Collectively, these changes will allow for the development of innovative program models, alleviate paperwork burdens, and support mixed income settings.

We believe the benefits of these changes will be significant for the children and families Head Start serves. Strengthening Head Start standards will improve child outcomes and promote greater success in school as well as produce higher returns on taxpayer investment. Reorganizing, streamlining, and reducing the requirements in the regulation will make Head Start less burdensome for existing grantees and more approachable for potential grantees, which may result in more organizations competing for Head Start grants. These changes are central to the Administration's belief that every child deserves an opportunity to succeed.

II. Tables

Start Printed Page 61297 Start Printed Page 61298 Start Printed Page 61299 Start Printed Page 61300 Start Printed Page 61301 Start Printed Page 61302Table 2—Redesignation Table

This final rule reorganizes and redesignates the Head Start Program Performance Standards under subchapter B at 45 CFR chapter XIII. We believe our efforts provide current and prospective grantees an organized road map on how to provide high-quality Head Start services.

To help the public readily locate sections and provisions from the previous performance standards that are reorganized and redesignated, we included redesignation and distribution tables in the NPRM. The redesignation table listed the previous section and identified the section we proposed would replace it. The distribution table in the NPRM listed previous provisions and showed whether we removed, revised, or redesignated them. We believe the public may continue to find the redesignation table useful here, so we included an updated version of it below.

Table 2—Redesignation Table

Previous section New section 1301.1 1303.2 1301.20 1305 1301.10 1303.3 1301.11 1303.12 1301.20 1303.4 1301.21 1303.4 1301.30 1303.10 1301.31 1302.90, 1302.102 1301.32 1303.5 1301.33 1303.31 1301.34 1304.5, 1304.7 1302.1 1304.1 1302.2 1305 1302.5 1304.2, 1304.3, 1304.4 1302.10 1304.20 1302.11 1304.20 1302.30 1304.30 1302.31 1304.31 1302.32 1304.32 1303.1 1304.1, 1303.30 1303.2 1305 1303.10 1304.1 1303.11 1304.3 1303.12 1304.4 1303.14 1304.5 1303.21 1304.6 1303.22 1304.6 1304.1 1302.1 1304.3 1305 1304.20 1302.42, 1302.33, 1302.41, 1302.61, 1302.46, 1302.63 1304.21 1302.30, 1302.31, 1302, 1302.35, 1302.60, 1302.90, 1302.34, 1302.33, 1302.46, 1302.21 1304.22 1302.47, 1302.92, 1302.15, 1302.90, 1302.41, 1302.42, 1302.46 1304.23 1302.42, 1302.44, 1302.31, , 1302.90, , 1302.46 1304.24 1302.46, 1302.45 1304.40 1302.50, 1302.52, 1302.80, 1302.18, 1302.34, 1302.51, 1302.30, 1302.18, 1302.81, 1302.46, 1302.52, 1302.70, 1302.71, 1302.72, 1302.22, 1302.82 1304.41 1302.53, 1302.63, 1302.70, 1302.71 1304.50 1301.1, 1301.3 1302.102, , 1301.4 1304.51 1302.101, 1302.90, 1303.23, 1302.102, 1301.3, 1303.32 1304.52 1302.101, 1302.91, 1302.90, 1302.91, 1302.21, 1303.3, 1302.93, 1302.94, 1302.92, 1301.5 1304.53 1302.31, 1302.21, 1302.47, 1302.22, 1302.23 1304.60 1302.102, 1304.2 1305.1 1302.10 1305.2 1305 1305.3 1302.11, 1302.102, 1302.20 1305.4 1302.12 1305.5 1302.13, 1302.14, 1305.6 1302.14 1305.7 1302.12, 1302.15, 1302.70 1305.8 1302.16 1305.9 1302.18 1305.10 1304.4 1306.3 1305 1306.20 1302.101, 1302.21, 1302.90, 1302.23, 1302.20 1306.21 1302.91 1306.23 1302.92 1306.30 1302.20, 1302.21, 1302.22, 1302.23 1306.31 1302.20 1306.32 1302.21, 1302.24, 1302.17, 1302.102, 1302.34, 1302.18 1306.33 1302.22, 1302.101 , 1302.91, 1302.35, 1302.44, 1302.23, 1302.31, 1301.4, 1302.47, 1302.45, 1302.24 1307.1 1304.10 Start Printed Page 61303 1307.2 1305 1307.3 1304.11 1307.4 1304.12 1307.5 1304.13 1307.6 1304.14 1307.7 1304.15 1307.8 1304.16 1308.1 1302.60 1308.3 1305 1308.4 1302.101, 1302.61, 1302.63, 1303.75 1308.5 1302.12, 1302.13 1308.6 1302.33, 1302.42, 1302.34, 1302.33 1308.18 1302.47 1308.21 1302.61, 1302.62, 1302.34 1309.1 1303.40 1309.2 1303.41 1309.3 1305 1309.4 1303.42, 1303.44, 1303.45, 1303.48, 1303.50 1309.21 1305, 1303.51, 1303.48, 1303.50, 1303.46, 1303.47, 1303.48, 1303.55, 1303.3 1309.22 1303.49, 1303.51 1309.31 1303.44, 1303.47 1309.33 1303.56 1309.40 1303.53 1309.41 1303.54 1309.43 1303.43 1309.52 1303.55 1309.53 1303.56 1310.2 1303.70 1310.3 1305 1310.10 1303.70, 1303.71, 1303.72 1310.14 1303.71 1310.15 1303.72 1310.16 1303.72 1310.17 1303.72 1310.20 1303.73 1310.21 1303.74 1310.22 1303.75 1310.23 1303.70 III. Background

a. Statutory Authority

This final rule is published under the authority granted to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services under sections 640, 641A, 642, 644, 645, 645A, 646, 648A, and 649 of the Head Start Act, Public Law 97-35, 95 Stat. 499 (42 U.S.C. 9835, 9836a, 9837, 9839, 9840, 9840a, 9841, 9843a, and 9844), as amended by the Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, Public Law 110-134, 121 Stat. 1363. In these sections, the Secretary is required to establish performance standards for Head Start and Early Head Start programs, as well as federal administrative procedures. Specifically, the Act requires the Secretary to “. . . modify, as necessary, program performance standards by regulation applicable to Head Start agencies and programs. . .” and explicitly directs a number of modifications, including “scientifically based and developmentally appropriate education performance standards related to school readiness that are based on the Head Start Child Outcomes Framework” and to “consult with experts in the fields of child development, early childhood education, child health care, family services . . ., administration, and financial management, and with persons with experience in the operation of Head Start programs.” [10] Not only did the Act mandate such significant revisions, there was also bipartisan and bicameral agreement in Congress that its central purpose was to update and raise the education standards and practices in Head Start programs.[11 12] As such, these program performance standards substantially build upon and improve the standards related to the education of children in Head Start programs.

b. Purpose of This Rule

This rule meets the statutory requirements Congress put forth in its 2007 bipartisan reauthorization of Head Start and addresses Congress's mandate that called for the Secretary to review and revise the Head Start Program Performance Standards.[13] Program performance standards are the foundation upon which Head Start programs design and deliver comprehensive, high-quality individualized services to support the school readiness of children from low-income families. They set forth requirements local grantees must meet to support the cognitive, social, emotional, and healthy development of children from birth to age five. They encompass requirements to provide education, health, mental health, nutrition, and family and community engagement services, as well as rules for local program governance and aspects of federal administration of the program. Start Printed Page 61304Program performance standards in this final rule build upon field knowledge and experience to codify best practices and ensure Head Start programs deliver high-quality services to the children and families they serve.

This final rule strengthens program standards so that all children and families receive high-quality services that will have a stronger impact on child development and outcomes and family well-being. The program performance standards set higher standards for curriculum, staff development, and program duration, all based on research and effective practice, while maintaining Head Start's core values of family engagement, parent leadership, and providing important comprehensive services to our nation's neediest children. At the same time, the final rule makes program requirements easier for current and future program leaders to understand and reduces administrative burden so that Head Start directors can focus on delivering high-quality early learning programs that help put children onto a path of success.

c. Rulemaking and Comment Processes

We sought extensive input to develop this final rule. We began the rulemaking process with consultations, listening sessions, and focus groups with Head Start staff, parents, and program administrators, along with child development and subject matter experts, early childhood education program leaders, and representatives from Indian tribes, migrant and seasonal communities, and other constituent groups. We heard from tribal leaders at our annual tribal consultations. We studied the final report of the Secretary's Advisory Committee on Head Start Research. We consulted with national organizations and agencies with particular expertise and longstanding interests in early childhood education. In addition, we analyzed the types of technical assistance requested by and provided to Head Start agencies and programs. We reviewed findings from monitoring reports and gathered information from programs and families about the circumstances of populations Head Start serves. We considered advances in research-based practices with respect to early childhood education and development, and the projected needs of expanding Head Start services. We also drew upon the expertise of federal agencies and staff responsible for related programs in order to obtain relevant data and advice on how to promote quality across all Head Start settings and program options. We reviewed the studies on developmental outcomes and assessments for young children and on the workforce by the National Academy of Sciences.[14 15] We also reviewed the standards and performance criteria established by state Quality Rating and Improvement Systems, national organizations, and policy experts in early childhood development, health, safety, maternal health, and related fields.

We published a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) on June 19, 2015 to solicit comments from the public. We extended the notice of proposed rulemaking comment period 30 days past our original deadline to September 17, 2015, to allow for more feedback from parents, grantees, and the Head Start community in general. We received, analyzed, and considered approximately 1,000 public comments to develop this final rule. Commenters included Head Start parents, staff, and management; national, regional, and state Head Start associations; researchers; early childhood, health, and parent organizations; policy think tanks; philanthropic foundations; Members of Congress; and other interested parties.

d. Overview of Major Changes From the NPRM

The public comments addressed a wide range of issues. We made many changes to the program performance standards in response to those comments, which range from minor to significant. The most significant changes fall under several categories: Service duration, the central and critical role of parents in Head Start, staff qualifications to support high-quality, comprehensive service delivery, and health promotion.

First, we made changes to this final rule in response to the many public comments we received on the proposal to increase the duration of services children receive in Head Start. The changes to the service duration requirements in the final rule reflect concerns about local flexibility and access to Head Start for low-income children and their families. Instead of requiring all Head Start center-based programs to operate for at least 6 hours per day and 180 days per year as proposed in the NPRM, we changed the requirement to a minimum of 1,020 annual hours of planned class operations, which grantees will phase in for all of their center-based slots over five years. Similarly for Early Head Start, we changed the requirement in the NPRM for center-based programs to operate at least 6 hours per day and 230 days per year to 1,380 annual hours in this rule, and allow two years for programs to plan and implement this increase in service duration. These requirements balance the importance of increasing service duration with allowing greater local flexibility and more time for communities to adapt and potential funding to be secured.

Research supports the importance of longer preschool duration in achieving meaningful child outcomes and preparing children for success in school.[16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] Shorter preschool programs may not have as much time to adequately support strong early learning outcomes for children and provide necessary comprehensive services.[24] [25] [26] In addition, the long Start Printed Page 61305summer break in most Head Start programs likely results in summer learning loss that undermines gains children make during the program year.[27] [28] [29] Furthermore, part-day programs can undermine parents' job search, job training, and employment opportunities.

In the NPRM, we proposed to increase the positive impact of Head Start programs serving three- to five-year-olds by increasing the minimum hours and days of operation and to codify long-standing interpretation of continuous services for programs that serve infants and toddlers, in concert with increasing standards for educational quality. Specifically, the NPRM proposed to require programs to serve three- to five-year-olds for at least 6 hours per day and 180 days per year and to require programs to serve infants and toddlers for a minimum of 6 hours per day and 230 days per year. Our proposal was consistent with research demonstrating the necessity of adequate instructional time to improve child outcomes and aligned with recommendations from the Secretary's Advisory Committee.[30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] However, though the research is clear that longer duration matters, there is no clarity on an exact threshold or combination of hours and days needed to achieve positive child outcomes. Therefore, in response to a significant number of public comments on the NPRM, including comments from the national, state, and regional Head Start associations, the final rule defines full school day and full school year services as 1,020 annual hours for Head Start programs and defines continuous services as 1,380 annual hours for Early Head Start programs, instead of setting a minimum number of hours per day and days per year for each program. These adjusted requirements will give programs more flexibility to design their program schedules to better meet children and community needs as well as align with local school district calendars, where appropriate.

To further address the comments about service duration and ensure a smooth transition for children and families, the final rule also includes a staggered approach to increasing service duration for Head Start preschoolers over the next five years. This gradual transition will allow programs more time to plan and implement changes while also increasing families' access to full school day Head Start services and ensuring more children receive the high-quality early learning services to help them arrive at kindergarten ready to succeed. The final rule also gives the Secretary the authority to reduce the proportion of each grantee's center-based slots required to operate for a full school day and full school year if the Secretary determines that such a reduction is needed to avert a substantial reduction in slots. We believe the requirements in the final rule strike an appropriate balance between setting the policy research demonstrates will best support positive outcomes for children and families, while minimizing reduction in the number of children and families Head Start can serve.

Second, we received comments that expressed concern that the proposed changes to family engagement services and governance would result in a reduction in emphasis on family engagement processes, parent leadership, and parent influence on program policy. This was not our intent. The intent of the NPRM was for the family engagement standards to incorporate the changes made to governance in the 2007 reauthorization and align with the groundbreaking work Head Start has led through the development of the Parent, Family, and Community Engagement Framework. Family engagement has always been at the foundation of Head Start, and as such, the final rule retains many of the proposed improvements to family services that integrate research-based practices and provide greater local flexibility to help programs better meet family needs. However, given the perception that the changes would limit the role of parents and families in Head Start, the final rule includes several changes to more effectively reflect and maintain the important role of Head Start parents in leading Head Start programs, as well as the importance of family engagement to the growth and success of Head Start children. Specifically, we restore a requirement for parent committees, maintain and strengthen family partnership services (including goal setting), and strengthen the requirements for impasse procedures to make it clear that the policy council plays a leadership role in the administration of programs, rather than functioning in an advisory capacity. It is our expectation that the revisions to the final rule will ensure all grantees, programs, and parents understand the foundational role parents of Head Start children play in shaping the program at the local and national level.

Third, this final rule includes several changes in response to comments that suggested Head Start should use the revision of the program performance standards to set a higher bar for the delivery of quality comprehensive services. Specifically, this final rule includes a greater emphasis on staff qualifications and competencies for health, disabilities, and family services managers, as well as staff who work directly with children and families in the family partnership process. The qualification requirements represent minimum credentials we believe are critical to ensuring high-quality services. However, because we also recognize the important role of experience and community connections for such staff, these requirements are only for newly hired staff and, in some cases, give programs the flexibility to support staff in obtaining the credentials within 18 months of hire.

In response to public comments that the NPRM was not strong enough in addressing some serious public health issues, this final rule includes changes Start Printed Page 61306that place a greater emphasis on certain health concerns, including childhood obesity prevention, health and developmental consequences of tobacco products and exposure to lead and support for mental health and social and emotional well-being. Given the prevalence of childhood obesity across the nation, especially among low-income children, we maintained important health and nutrition requirements and made specific changes to ensure Head Start actively engage in its prevention in the classroom and through the family partnership process. Given the serious health and developmental consequences of children's exposure to tobacco products, including second and third hand smoke, and to lead, we have explicitly required that programs offer parents opportunities to learn about these health risks and safety practices they can employ in their homes. We significantly strengthened the breadth and clarity on the requirements for programs to use mental health consultants to ensure Head Start programs are supporting children's mental health and social and emotional well-being. The final rule includes new provisions in the requirements for health, education, and family engagement services that elevate the role of Head Start programs in addressing these public health problems.

Additionally, through ongoing tribal consultations and the public comment process, we received important feedback from the American Indian and Alaska Native community. We made a number of changes specifically related to American Indian and Alaska Native programs based on these public comments and the unique and important sovereign relations with tribal governments. We added a new provision that for the first time makes it explicit that programs serving American Indian and Alaska Native children may integrate efforts to preserve, revitalize, restore, or maintain tribal language into their education services. We also clarified that, due to tribal sovereignty, American Indian and Alaska Native programs only need to consider whether or not they will participate in early childhood systems and activities in the state in which they operate.

In addition to these changes, the final rule maintains numerous changes proposed in the NPRM to strengthen program performance standards so all children and families receive high-quality services that will improve child outcomes and family well-being. We maintained and made important changes to strengthen service delivery. For example, we updated the prioritization criteria for selection and recruitment; made improvements to promote attendance; prohibited expulsion for challenging behaviors; strengthened services for children who are dual language learners (DLLs); and ensured critical supports for children experiencing homelessness or in foster care. Throughout the final rule we have made changes in response to public comments to make language clearer or more focused on outcomes rather than processes.

IV. Discussion of General Comments on the Final Rule

We received approximately 1,000 public comments on the NPRM with many commenters supporting our overall approach to revising the Head Start Program Performance Standards. Commenters appreciated our reorganization and streamlining, and agreed this made the standards more transparent and easier to understand. Commenters generally supported our approach to systems-based standards that are more focused on outcomes and less prescriptive and process-laden. They did note that how OHS monitored these standards would affect their implementation and impact. Commenters also appreciated our research-based approach. They noted our education and child development standards focused on the elements most important for supporting strong child outcomes. Commenters supported standards in the NPRM to improve services to children who are DLLs and their families. Commenters also supported our emphasis on reducing barriers and improving services to children experiencing homelessness and children in foster care. Overall, commenters agreed our proposal would improve program quality, clarify expectations, and reduce burden on programs.

We received a range of comments on our proposal to increase the minimum service duration for Head Start and Early Head Start programs. Some commenters supported the proposal to increase duration, citing the research base and its importance to achieving strong child outcomes. Many commenters stated that without sufficient funds, this would lead to a reduction in the number of children and families Head Start served and this would be an unacceptable outcome. Other commenters raised concern or opposition for a variety of other reasons. We discuss and respond to these concerns in detail our discussion of part 1302, subpart B.

Many commenters were concerned that the NPRM overall reflected a reduced commitment to the role of parents in Head Start. They also pointed to specific proposals in different subparts and sections, which they stated contributed to a diminished role for parents. It was not our intent to diminish the role of parents in the Head Start program, and we have revised provisions in the final rule to ensure our intent for parent engagement is appropriately conveyed. We believe parent engagement is foundational to Head Start and essential to achieving Head Start's mission to help children succeed in school and beyond. We address specific comments on parent involvement and engagement and our responses in the discussions of the relevant sections.

Many commenters believed there were excessive references to the Act. They asked that the final regulation translate the references to the Act with specific language or brief excerpts from the Act. We maintained the same approach as we proposed in the NPRM to reference the provisions in the Act so that the regulation will not become obsolete if the provisions in the Act change. However, we intend to issue a training and technical assistance document that integrates language from the Act into the same document as the program performance standards to address commenters' interest in having a single document.

We also received other general comments or comments not tied to a specific section or provision of the rule. For example, some commenters offered general support for the Head Start program and noted it was important for Head Start to continue. One commenter thought we should have included examples of excellent Head Start programs. Commenters stated their overall opposition to the Head Start program or the NPRM as a whole, and others did not want Head Start program to continue to receive funding. Commenters stated that services for DLLs were emphasized too heavily in the regulation or that the standards for DLLs were too prescriptive. We believe DLLs are an appropriate priority in the regulation because the provisions reflect requirements in the Act and because it is important programs effectively serve DLLs because they are a rapidly growing part of both Head Start and the broader United States population. Commenters also offered specific suggestions on ways to clarify, enhance, or add language relevant to serving culturally and linguistically diverse children and families, including children who are DLLs throughout the NPRM. We incorporated some of the suggestions into the final rule but felt some were Start Printed Page 61307already adequately covered while others were not feasible to include in regulation. We discuss these comments as appropriate in the relevant sections of the preamble.

Commenters also pointed out technical problems, such as incorrect cross references, typographical errors, or small inconsistencies in related provisions. We corrected these errors and made other needed technical changes, including edits to ensure descriptive titles throughout the final rule. Commenters also requested that we update existing data collections to account for changes in the program performance standards. As we make changes to the Head Start Program Information Report (PIR) and other data collections we sponsor, we will consider the final rule, but this is not a regulatory issue.

V. Discussion of Section by Section Comments on the Final Rule

We received many comments about changes we proposed to specific sections in the regulation. Below, we identify each section, summarize the comments, and respond to them accordingly.

Program Governance; Part 1301

This part describes program governance requirements for Head Start agencies. Program governance in Head Start refers to the formal structure in place “for the oversight of quality services for Head Start children and families and for making decisions related to program design and implementation” as outlined in section 642(c) of the Act. The Act requires this structure include a governing body and a policy council, or a policy committee at the delegate level. These groups have a critical role in oversight, design and implementation of Head Start and Early Head Start programs. The governing body is the entity legally and fiscally responsible for the program. The policy council is responsible for the direction of the program and must be made up primarily of parents of currently enrolled children. Parent involvement in program governance reflects the fundamental belief, present since the inception of Project Head Start in 1965, that parents must be involved in decision-making about the nature and operation of the program for Head Start to be successful in bringing about substantial change.[36]

We revised previous program governance requirements primarily to conform to the Act. We received many comments on part 1301. Below we discuss these comments and our rationale for any changes to the regulatory text in this subpart.

General Comments

Comment: Many commenters offered reactions to part 1301. Commenters expressed general support for the requirements, indicating they reflect the statutory requirements, improve transparency, maintain the important role of parents, and increase local flexibility.

Other commenters stated this part was unnecessarily complicated for parents, policy council members, and staff to follow as presented in the NPRM. Many commenters suggested all governance requirements be clearly stated in the rule rather than referenced with statutory citation in order to improve clarity and reduce burden for programs, parents, and others.

Response: As noted previously, we maintained the approach to cross reference to the Act so that the regulations will not become obsolete if the provisions in the Act change. However, we plan to issue a training and technical assistance document that incorporates the language from the Act with the regulatory language.

Comment: Some commenters suggested we failed to address the role of shared governance in the Head Start program, and that we relied too heavily on the Act, which is vague and ambiguous, and leaves grantees wondering about the proper balance between the role and responsibility of the governing body and the policy council. These commenters ask that we include more specificity about shared governance in the final rule.

Response: We continue to believe the best approach is to align the governance requirements in the rule with the language and requirements specified in the Act. The statutory language has directed the governance of Head Start programs since it was passed in 2007 and there have not been any significant problems with this approach.

Comment: Commenters asked that we include “Tribal Council” wherever the phrase “governing body” occurs.

Response: We do not believe this is necessary, since the tribal council is acting as the governing body.

Section 1301.1 Purpose

This section reiterates the requirement in section 642(c) of the Act regarding the structure and purpose of program governance. The structure as outlined in the Act includes a governing body, a policy council, and, for a delegate agency, a policy committee. We restored the requirement from the previous performance standards that programs also have parent committees as part of the governance structure, and we discuss this requirement in more detail in § 1301.4. This section emphasizes that the governing body has legal and fiscal responsibility to administer and oversee the program, and the policy council is responsible for the direction of the program including program design and operations and long- and short-term planning goals and objectives.

Comment: Commenters recommended that we revise the language in this section to state clearly that each agency must establish a policy council.

Response: We proposed in the NPRM to use the term “policy group” to encompass the policy council and the policy committee more concisely. We defined “policy group” to mean “the policy council and policy committee at the delegate level.” After further consideration and in response to comments, we reverted to using “policy council and policy committee at the delegate level.” It is lengthier but clearer. Instead of introducing a new term, we are remaining consistent with the Act.

Comment: Some commenters raised concerns with the policy council being responsible for the direction of the Head Start program. Commenters stated it was unclear how the policy council could be effective in that role. Others said both the governing body and the policy council should be responsible for the direction of the program or that this responsibility should rest solely with the governing body.

Response: We maintained the language proposed in the NPRM because it is the statutory requirement in the Act that the policy council is responsible for the direction of the Head Start and Early Head Start programs.

Section 1301.2 Governing Body

In the NPRM, this section described training requirements; however, we moved training requirements to § 1301.5 and this section now pertains to the governing body.

This section includes requirements for the composition of the governing body and its duties and responsibilities. It aligns with the Act's detailed requirements for the composition and responsibilities of the governing body. This section requires governing body members use ongoing monitoring results, data from school readiness goals, the information specified in section 642(d)(2) of the Act, and the information in § 1302.102 to conduct their responsibilities. Paragraph (c) Start Printed Page 61308permits a governing body, at its own discretion, to establish advisory committees to oversee key responsibilities related to program governance, consistent with section 642(c)(1)(E)(iv)(XI) of the Act. Below we address comments and requests for clarification.

Comment: We received some comments on the governing body's duties and responsibilities that addressed the duties and responsibilities of both the governing body and the policy council together. Some commenters requested we provide a clear illustration of the responsibilities and powers of the governing body and policy council by including a chart or diagram. Commenters also provided specific suggestions for revisions, such as: Add language from the previous performance standards on the duties and responsibilities of the governing body and policy council; remove language specific to ongoing monitoring and school readiness goals, as this is addressed in another section; and require that program goals inform the governing body and policy council.

Response: We did not include a diagram or chart in this rule because we believe the governance provisions in the rule and in the Act are clear. In response to comments, we added to paragraph (b)(2) a cross-reference to the requirement in § 1302.102 related to establishing and achieving program goals. By adding this cross reference, we are requiring governing bodies to use this information to conduct their responsibilities.

Comment: Some commenters offered support and raised concerns about the governing body's duties and responsibilities as laid out in paragraph (b). Some commenters supported the requirement that the governing body use ongoing monitoring results and school readiness goals to conducts it responsibilities, in addition to what is required in section 642(d)(2) of the Act. Some commenters suggested we enhance or clarify language about when programs needed to report to the responsible HHS official. Commenters also requested clarification about the governing body's responsibility to establish, adopt, and update Standards of Conduct, including reporting any violations to the regional office and about self-reporting requirements for immediate deficiencies.

Response: The Act specifies that the governing body is responsible for establishing, adopting, and periodically updating written standards of conduct, so we believe this is addressed because we incorporated this requirement from the Act. We revised § 1302.90(a) to clarify the role of the governing body in standards of conduct, which we had inadvertently left out of that standard. We did not revise the requirement about self-reporting because it is addressed in § 1302.102.

Comment: Many commenters stated the proposed rule was unclear about conflicts of interest. Commenters requested clarification about this provision and recommended adding language that mirrors the IRS Form 1023 Instructions, Appendix A, Sample Conflicts of Interest Policy.

Response: We did not make changes to this language. There is guidance in the nonprofit community about the various ways to structure and apply a conflict of interest policy. If an agency wants to adopt the IRS rules, that would be one option, but it might not be the right option for all programs. Additionally, the governing body is required to develop a written conflict of interest policy, which can provide greater clarity than the overarching federal requirements.

Comment: We received comments on advisory committees described in paragraph (c). Some commenters requested additional clarification, including who the advisory board is and what groups should be included and whether the governing body may establish more than one advisory committee. Others commenters suggested revisions to the advisory committee's role advisory committee with respect to the governing body. For example, commenters stated that all areas of program governance, especially supervision of program management, should be left in the hands of the Board of Directors or the established governing body. Some commenters noted that advisory committees should not make decisions about program governance because that is not advisory in nature. Other commenters made specific suggestions for the language related to advisory committees, such as eliminating the composition requirements, eliminating the requirement that advisory committees be established in writing, and differentiating between advisory committees that act as sub-boards versus other advisory committees.

Response: To improve clarity, we revised and streamlined paragraph (c). We clarified that governing bodies may establish one or more advisory committees. We removed some of the more prescriptive requirements, such as written procedures or composition requirements, and explicitly required that when the advisory committee is overseeing key responsibilities related to program governance, it is the responsibility of the governing body to establish the structure, communication and oversight in a way that assures the governing body retains its legal and fiscal responsibility for the Head Start agency. This allows the governing body flexibility to structure their advisory committee but requires that they retain legal and fiscal responsibility for the Head Start agency. We also require the governing body to notify the responsible HHS official of its intent to establish such an advisory committee.

Section 1301.3 Policy Council and Policy Committee

In this section, we retain a number of requirements from the previous program standards and included requirements to conform to the Act. In paragraph (a), we retain the requirement for agencies to establish and maintain a policy council at the agency level and a policy committee at the delegate level, consistent with section 642(c)(2) and (3) of the Act. Paragraph (b) outlines the composition of policy councils, and policy committees at the delegate level, consistent with the Act. Paragraph (c) outlines the duties and responsibilities for the policy council and the policy committee to conform to the Act and is largely unchanged from the NPRM. Paragraph (d) addresses the term of service for policy council and policy committee members.

Comment: Commenters recommended we include all of the statutory language from section 642(c)(2)(A) of the Act in this section, rather than summarizing that the policy council has responsibility for the direction of the program. Another recommended the policy committee at the delegate level be renamed to “Policy Action Committee” to eliminate programs from using “PC” for both policy council and policy committee.

Response: We did not revise the concise reference to the policy council having responsibility for the direction of the program, although the Act's more expansive language is still part of the requirement. We maintain the terminology as it exists in the Act and did not rename “policy committee” at the delegate level.

Comment: Commenters supported the standard in paragraph (b) to require proportional representation on the policy council by program option but also recommended revisions and asked for additional clarification. For example, commenters requested clarification on what proportional representation means and how to implement it within different program types.

Other commenters expressed support for the requirement that the majority of Start Printed Page 61309policy council members be parents but requested that language be added to the rule, rather than just citing the Act. Others requested clarification on how appropriate composition will be maintained and consistent with the Act when parents drop out.

Response: We revised paragraph (b) to clarify that parents of children currently enrolled in “each” program option must be proportionately represented on the policy council or the policy committee. We believe programs should have the flexibility to specify in their policies and procedures how the composition requirements will be maintained when parents drop out and did not make revisions to address this.

Comment: Commenters expressed disagreement with language in the preamble to the NPRM stating, “We propose to remove current § 1304.50(b)(6) which excludes staff from serving on policy councils or policy committees with some exceptions. . .”. Commenters expressed confusion and stated this language has been interpreted to mean staff would be allowed to participate as a policy council or policy committee member. Though one commenter expressed support for allowing staff to serve on the policy council because they have field experience and skills to make informed decision, the commenters generally stated it is a conflict of interest and could inhibit parent driven decision-making.

Response: In the NPRM, we proposed to remove § 1304.50(b)(6), which excludes staff from serving on policy councils or policy committees with some exceptions, because it is superseded by the Act. In other words, the conflict of interest language in the Act, as well as the Act's clarity on who can serve on the policy council, means we no longer need the prohibition on staff serving on policy council or policy committee. However, commenters noted the exception related to substitute teachers is helpful and clarifying for programs. Therefore, we added the majority of the language on this topic from the previous performance standards back into paragraph (b)(2) to ensure clarity.

Comment: Commenters stated the Act gives the policy council responsibilities outside its scope of authority, and that the final rule should be modified to include language from the previous regulation related to duties and responsibilities. Commenters recommended we instead should focus the responsibilities of the policy council on program issues.

Response: In the final rule, we maintained the alignment with the Act with respect to the duties and responsibilities of the policy council. We did not add the requested language from the previous regulation because it has been superseded by the Act.

Comment: Some commenters requested that we clarify in the final rule the role of the policy council in hiring and terminating staff.

Response: We did not include a specific provision on the role of policy council in hiring and terminating program staff because we rely on the language in section 642(c)(2)(D)(vi) of the Act.

Comment: Many commenters supported allowing programs to establish in their bylaws five one-year terms for policy council members as opposed to three. Commenters said the change would support continuity, increase understanding of the complexities of the Head Start program and regulation, and promote investment in the policy council.

Some commenters opposed the option of extending policy council terms from three one-year terms to five. They stated that five years is too long, that parents may not have children in the program for five years, and that a shorter term would allow for more new members.

Response: We did not revise this provision. This rule provides programs the discretion to establish in their bylaws the number of one-year terms of policy council members up to five one-year terms. Programs have the discretion of setting a lower limit.

Comment: We received comments about the term “reasonable expenses” in paragraph (e). Commenters recommended we add a definition of “reasonable expenses,” allow that all participants on the policy council/committee be reimbursed for “reasonable expenses,” and allow agencies to develop their own policies and procedures to determine eligibility based on the need of their communities.

Response: We did not clarify the definition of “reasonable” but allow programs to make a determination. We clarified that eligibility for the reimbursement is only for low-income members.

Section 1301.4 Parent Committees

Comment: We received many comments about our proposal to remove the requirement for the parent committee. Some commenters supported the proposal to remove the parent committee requirement. They emphasized that there are more meaningful and inclusive ways to engage parents that could allow for individual program flexibility and innovation. These commenters suggested that the focus should instead be on providing opportunities for parents to learn about their children and engage them in teaching and learning and on family engagement outcomes.

Some commenters supported the removal of the parent committee requirement with reservations, but were concerned about the challenges it would pose for electing policy council representatives, about the loss of the benefits to parents previously derived from participation in parent committees, and about the perceived erosion of a core philosophy of Head Start. Others asked that the revised requirement ensure a structure for representing parent views and offering parents other opportunities for engagement.

Many commenters opposed the removal of parent committees. Commenters urged that we reinstate the parent committee requirement as it existed in the previous standards. These commenters stressed that parents are foundational to Head Start and that parent committees are a long-standing cornerstone of the program. They stated removing the requirement for parent committees would weaken Head Start parent engagement and diminish parents' role. Commenters noted that parent committees stimulate parent participation in the program, help parents develop leadership, advocacy and other useful skills, and are critical to developing membership for policy council. Commenters disagreed with our statement in the NPRM that parent committees do not work in all models, such as Early Head Start—Child Care Partnership (EHS-CCP) grantees, and suggested we help these grantees learn how to incorporate this valuable experience for parents in order to infuse a higher level of quality into child care settings. Commenters were also concerned that the removal of parent committee would result in the loss of in-kind contributions from parent involvement.

Some commenters opposed the removal of the parent committee requirement and asked that we make modifications or recommended alternative language in the final rule if the parent committee requirement is removed. These commenters stated similar concerns to those who requested that we reinstate the requirement, but made suggestions for the final rule, such as to allow individual programs to determine the design and structure of parent committees, or to support flexibility in local design of parent committees and proposals for alternate mechanisms to engage families. Some of these commenters believed that parent committees are not for all parents. These Start Printed Page 61310commenters asked that programs be required to have a process in place that ensures all parents of enrolled children have local site opportunities to actively share their ideas, that parents understand the process for elections or nominations to serve on the policy council, and that a communication system exist to share information between parents attending local sites and the policy council and governing body.

Response: We restored a requirement for a parent committee in this part and in a new § 1301.4. We also note that a parent committee is part of the formal governance structure in § 1301.1. This section clearly outlines the requirements for a program in establishing a parent committee and the minimum requirements for parent committees, which are consistent with all of the substantive requirements from the previous performance standards. We maintain the requirement that a program must establish a parent committee comprised exclusively of parents of currently enrolled children as early in the program year as possible and that the parent committee must be at the center level for center-based programs and at the local program level for other program options. In addition, in response to comments, we require programs to ensure parents of currently enrolled children understand the process for elections to policy council or policy committee or other leadership roles. Also as suggested by commenters, we allow programs flexibility within the structure of parent committees to determine the best methods and strategies to engage families that are most effective in their communities as long as the parent committee carries out specific minimum responsibilities. It requires that parent committees (1) advise staff in developing and implementing local program policies, activities, and services to ensure they meet the needs of children and families, and (2) participate in the recruitment and screening of Early Head Start and Head Start employees, both of which are retained from the previous performance standards. In response to comments we have added a requirement that the parent committee have a process for communication with the policy council and policy committee at the delegate level.

Section 1301.5 Training

This section describes the training requirements for the governing body, advisory committee members, and the policy council. It reflects section 642(d)(3) of the Act that requires governing body and policy council members to have appropriate training and technical assistance to ensure they understand the information they received and can oversee and participate in the agency's programs effectively. We moved this section from § 1301.2 in the NPRM to this placement in the final rule to improve overall clarity of part 1301. We discuss comments and our responses below.

Comment: We received comments that requested clarification or suggested ways to improve clarity. We also received comments that expressed opposition for the requirement. For example, commenters requested clarification on what is considered “appropriate” training and what is included in training. One commenter requested clarification on the inclusion of advisory committee members in the training. Commenters recommended we move this section out of § 1301.2, and others recommended we improve clarity by cross-referencing training requirements in another section. Some commenters opposed our requirement that governing bodies be trained on the standards because they thought it was unrealistic to expect Boards to have knowledge of all the operating standards and it detracted from getting input from governing bodies on program outcomes.

Response: We retained this requirement because it is required by the Act and because we believe governing bodies cannot effectively fulfill their program management responsibilities unless they have an understanding of the broader program requirements. Since governing bodies can choose to establish advisory committees, we included advisory committee members, who may be different individuals than governing body members, in this requirement.

To improve clarity, we moved these standards from § 1301.2 to this section so that it follows sections with the requirements for all components of an agency's formal governance structure. We revised the section to include a cross reference to training requirements in § 1302.12.

Section 1301.6 Impasse Procedures

This section on impasse procedures was found in § 1301.5 in the NPRM and is now § 1301.6 in the final rule. It describes procedural requirements for resolving disputes between an agency's governing body and policy council. We received many comments on our proposed impasse procedures. Many commenters believed our proposed impasse procedures weakened the role of parents in the Head Start program. They stated that we relegated the policy council, the majority of which is comprised of parents, to an advisory role by allowing the governing body the final decision when an impasse remained unresolved. In response to comments, we revised the impasse procedures. A discussion of the comments and our response is below.

Comment: Many commenters opposed our proposal for the dispute resolution and impasse procedures. Commenters stated our impasse procedure proposal contributed to a broader weakening of the role of parents in Head Start because it tilted the power balance toward the governing body and away from the policy council. They also stated that the standards conflicted with other program performance standards in this section and requirements in the Act. For example, they stated the proposal conflicted with the requirement for “meaningful consultation and collaboration about decisions of the governing body and policy council.” Commenters stated that conflicts often result from issues related to the direction of the program, which is the responsibility of the policy council. These commenters suggested that the proposed requirements amount to capitulation to the will of the governing body and are not actually impasse procedures, in contradiction with the Act's requirement. Others commenters noted further contradiction given the standards would require the governing body and policy council to work together yet exclude the policy council and allow the governing body to make the final decision. Some commenters stated that they embrace shared governance and provided examples of how the voice of parents has been critical to their decision-making during, for example, sequestration or previous impasses. Commenters made recommendations, such as adding formal mediation, strengthening the language related to “meaningful consultation and collaboration about decisions of the governing body and the policy council,” referring to the impasse procedures as a consensus-building process, and establishing an independent arbitrator or third party to resolve disputes between the governing body and policy council.

We also received comments supporting the impasse procedures proposed in the NPRM. Some of these commenters stated that it is appropriate for the governing body, since they bear legal and fiscal responsibility, to make the ultimate decisions on issues related to the Head Start program after taking into consideration the recommendations of the policy council and policy committee, if applicable. Further, commenters asked for additional Start Printed Page 61311clarification about our proposed requirements, including the timeline for resolution.

Response: For clarity, we included the statutory language that requires “meaningful consultation and collaboration about decisions of the governing body and policy council,” and we maintained requirements from the previous performance standards about these bodies jointly establishing written procedures for resolving internal disputes. We revised the requirements in this section to clarify the role of policy councils in the governance of Head Start programs, including processes to resolve conflicts with the governing body in a timely manner, and we included more specificity about what impasse procedures must include in order to better articulate the balanced process. In paragraph (b), we included a new standard that requires that in the event the decision-making process does not result in a resolution of the impasse, the governing body and policy council must select a mutually agreeable third party mediator and participate in a formal process that leads to a resolution. In paragraph (c), we require the governing body and policy council to select a mutually agreeable arbitrator, whose decision will be final, if no resolution resulted from mediation. Due to tribal sovereignty, we excluded American Indian and Alaska Native programs from the requirement in paragraph (c) to use an arbitrator.

Program Operations; Part 1302

Overview

In § 1302.1, we made a technical change to remove paragraph (a) because the content of this paragraph was already included in the statutory authority for this rule and for this part and is therefore unnecessary to repeat here. Therefore what was paragraph (b) in the NPRM is an undesignated paragraph in the final rule.

Eligibility, Recruitment. Selection, Enrollment and Attendance; Subpart A

In this subpart, we combined all previous requirements related to child and family eligibility, and program requirements for the recruitment, selection, and enrollment of eligible families. We updated these standards to reflect new priorities in the Act, including a stronger focus on children experiencing homelessness and children in foster care. We added new standards to reflect the importance of attendance for achieving strong child outcomes. Further, we included new standards to clarify requirements for children with persistent and disruptive behavioral issues as well as new standards to support programs serving children from diverse economic backgrounds, when appropriate. Commenters supported our reorganization of these requirements and our emphasis on special populations. Commenters were particularly appreciative of the standards throughout the section that were designed to reduce barriers to the participation of children experiencing homelessness. We made technical changes for improved clarity. We discuss additional comments and our responses below.

General Comments

Comment: Commenters recommended adding language that specifically encouraged the recruitment and enrollment of children who are culturally and linguistically diverse, and/or prioritizing linguistically diverse children for enrollment.

Response: We do not think it is necessary to explicitly encourage recruitment or prioritization of culturally and linguistically diverse children. Twenty-nine percent of Head Start children come from homes where a language other than English is the primary language.[37] Additionally, as described in § 1302.11(b)(1)(i), the community assessment requires programs to examine the eligible population in their service area, including race, ethnicity, and languages spoken. A program must then use this information when it establishes selection criteria and prioritization of participants, as described in § 1302.14(a)(1).

Section 1302.10 Purpose

This section provides a general overview of the content in this subpart. We received no comments directly for this section but made changes to be consistent with revisions in § 1302.11.

Section 1302.11 Determining Community Strengths, Needs, and Resources

This section includes the requirements for how programs define a service area for their grant application and the requirements for a community assessment. We streamlined the standards to improve clarity and reduce bureaucracy. In addition, we eliminated a prohibition on overlapping service areas, added new data as required by the Act for consideration in the community assessment to ensure community needs are met, and aligned the community assessment to a program's five-year grant cycle. We also required that programs consider whether they could serve children from diverse economic backgrounds in addition to the program's eligible funded enrollment in order to support mixed-income service delivery, which research suggests benefits children's early learning.[38 39] Below, we summarize and respond to the comments we received.

Comment: Many commenters opposed or expressed concern about our proposal to eliminate the prohibition on overlapping service areas. For example, commenters stated that overlapping service areas will be confusing and will cause conflict because of competition between grantees. Many commenters suggested we include a process for mediation when there are disputes. Commenters supported our decision to remove the prohibition on overlapping service areas.

Response: We believe removing the prohibition on overlapping service areas gives greater flexibility to local programs in a manner that will benefit the children and families they serve. Grantees may request additional guidance through the system of training and technical assistance. Therefore, we did not reinstate the prohibition on overlapping service areas in this rule.

Comment: We received a few different recommendations for additional criteria for defining service area. For example, many commenters recommended we include parents' job locations as part of the service area.

Response: While the service area is based on children's residence, this rule, as well as the previous regulation, is silent on whether a program can enroll a child that lives outside of the service area if their parents work in that area. We believe programs already have the flexibility to determine whether a child should be enrolled at a program closer to a parent's workplace and will clarify any existing sub-regulatory guidance to reflect this flexibility. We made no changes to this provision.

Comment: We received suggestions for paragraph (b)(1) to more explicitly address the purpose and the goal of the community needs assessment, to add additional or change criteria to the data (either on the five-year cycle or annually), and to provide more guidance on how programs should Start Printed Page 61312obtain data for the community needs assessment.

Response: We made changes to the section title and clarified that the community assessment should be strengths-based. We think these changes, together with using the full name of the community assessment—“community wide strategic planning and needs assessment”—better reflect the purpose of the assessment. We revised paragraph (b)(1) to clarify that this list is not exhaustive, and reorganized the list to make it more logically flow. We also revised paragraph (b)(1)(ii) to also include prevalent social or economic factors that impact their well-being. We did not believe additional data requirements were necessary because programs already have the flexibility to include other relevant data in their community assessments. We clarified in paragraph (b)(1)(ii) that homelessness data should be obtained in collaboration with McKinney-Vento liaisons to the extent possible, but it is important that all programs consider the prevalence of homelessness in their community, however possible. The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness has identified data gaps in tribal communities on young children experiencing homelessness, so we recognize tribal programs may need to utilize alternative methods to ensure they fully consider the prevalence of homelessness in their communities.

Comment: We received comments about our proposal in paragraph (b)(1) to change the community assessment from a three-year to a five-year timeline that would align with a program's five-year grant cycle. Some commenters supported this change because it removed unnecessary burden on programs. Commenters expressed concern that communities change rapidly and that five years is not frequent enough to review community needs.

Response: We think we strike the right balance between ensuring programs regularly assess and work to meet their community needs through an annual re-evaluation of particular criteria described in paragraph (b)(2) and § 1302.20(a)(2) and reduction of undue burden through alignment of the community assessment to the five-year grant cycle. We made no revisions to this timeline.

Comment: Many commenters recommended we change the requirement in paragraph (b)(2) that programs must annually review and update the community assessment to reflect any significant changes to the availability of publicly-funded full-day pre-kindergarten. These commenters expressed concern that public pre-kindergarten programs may not meet the needs of at-risk families because they do not offer a full spectrum of comprehensive services. Commenters offered specific suggestions for other community demographics to be considered in the annual review.