-

Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 9544

AGENCY:

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), DOT.

ACTION:

Notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM).

SUMMARY:

The FAA is proposing to amend its regulations to adopt specific rules to allow the operation of small unmanned aircraft systems in the National Airspace System. These changes would address the operation of unmanned aircraft systems, certification of their operators, registration, and display of registration markings. The proposed rule would also find that airworthiness certification is not required for small unmanned aircraft system operations that would be subject to this proposed rule. Lastly, the proposed rule would prohibit model aircraft from endangering the safety of the National Airspace System.

DATES:

Send comments on or before April 24, 2015.

ADDRESSES:

Send comments identified by docket number FAA-2015-0150 using any of the following methods:

- Federal eRulemaking Portal: Go to http://www.regulations.gov and follow the online instructions for sending your comments electronically.

- Mail: Send comments to Docket Operations, M-30; U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE., Room W12-140, West Building Ground Floor, Washington, DC 20590-0001.

- Hand Delivery or Courier: Take comments to Docket Operations in Room W12-140 of the West Building Ground Floor at 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE., Washington, DC, between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, except Federal holidays.

- Fax: Fax comments to Docket Operations at 202-493-2251.

Privacy: In accordance with 5 U.S.C. 553(c), DOT solicits comments from the public to better inform its rulemaking process. DOT posts these comments, without edit, including any personal information the commenter provides, to www.regulations.gov,, as described in the system of records notice (DOT/ALL-14 FDMS), which can be reviewed at www.dot.gov/privacy.

Docket: Background documents or comments received may be read at http://www.regulations.gov at any time. Follow the online instructions for accessing the docket or go to the Docket Operations in Room W12-140 of the West Building Ground Floor at 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE., Washington, DC, between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, except Federal holidays.

Start Further InfoFOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

For technical questions concerning this action, contact Lance Nuckolls, Office of Aviation Safety, Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration Office, AFS-80, Federal Aviation Administration, 490 L'Enfant Plaza East, SW., Suite 3200, Washington, DC 20024; telephone (202) 267-8447; email UAS-rule@faa.gov.

For legal questions concerning this action, contact Alex Zektser, Office of Chief Counsel, International Law, Legislation, and Regulations Division, AGC-220, Federal Aviation Administration, 800 Independence Avenue SW., Washington, DC 20591; telephone (202) 267-3073; email Alex.Zektser@faa.gov.

End Further Info End Preamble Start Supplemental InformationSUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Authority for This Rulemaking

This rulemaking is promulgated under the authority described in the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (Public Law 112-95). Section 333 of Public Law 112-95 directs the Secretary of Transportation [1] to determine whether “certain unmanned aircraft systems may operate safely in the national airspace system.” If the Secretary determines, pursuant to section 333, that certain unmanned aircraft systems may operate safely in the national airspace system, then the Secretary must “establish requirements for the safe operation of such aircraft systems in the national airspace system.” [2]

This rulemaking is also promulgated pursuant to 49 U.S.C. 40103(b)(1) and (2), which charge the FAA with issuing regulations: (1) To ensure the safety of aircraft and the efficient use of airspace; and (2) to govern the flight of aircraft for purposes of navigating, protecting and identifying aircraft, and protecting individuals and property on the ground. In addition, 49 U.S.C. 44701(a)(5), charges the FAA with prescribing regulations that the FAA finds necessary for safety in air commerce and national security.

Finally, the model-aircraft component of this rulemaking incorporates the statutory mandate in section 336(b) that preserves the FAA's authority, under 49 U.S.C. 40103(b) and 44701(a)(5), to pursue enforcement “against persons operating model aircraft who endanger the safety of the national airspace system.”

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms Frequently Used in This Document

AC Advisory Circular

AGL Above Ground Level

ACR Airman Certification Representative

ARC Aviation Rulemaking Committee

ATC Air Traffic Control

CAFTA-DR Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement

CAR Civil Air Regulation

CFI Certified Flight Instructor

CFR Code of Federal Regulations

COA Certificate of Waiver or Authorization

DPE Designated Pilot Examiner

FR Federal Register

FSDO Flight Standards District Office

ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization

NAFTA North American Free Trade Agreement

NAS National Airspace System

NOTAM Notice to Airmen

NPRM Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

NTSB National Transportation Safety Board

PIC Pilot in Command

Pub. L. Public Law

PMA Parts Manufacturer Approval

TFR Temporary Flight Restriction

TSA Transportation Security Administration

TSO Technical Standard Order

UAS Unmanned Aircraft System

U.S.C. United States Code

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose of the Regulatory Action

B. Summary of the Major Provisions of the Regulatory Action

C. Costs and Benefits

II. Background

A. Analysis of Public Risk Posed by Small UAS Operations

B. Current Statutory and Regulatory Structure Governing Small UAS

C. Integrating Small UAS Operations Into the NAS

III. Discussion of the Proposal

A. Incremental Approach and Privacy

B. Applicability

1. Air Carrier Operations

2. External Load and Towing Operations

3. International Operations

4. Foreign-Owned Aircraft That Are Ineligible for U.S. RegistrationStart Printed Page 9545

5. Public Aircraft Operations

6. Model Aircraft

7. Moored Balloons, Kites, Amateur Rockets, and Unmanned Free Balloons

C. Definitions

1. Control Station

2. Corrective Lenses

3. Operator and Visual Observer

4. Small Unmanned Aircraft

5. Small Unmanned Aircraft System (small UAS)

6. Unmanned Aircraft

D. Operating Rules

1. Micro UAS Classification

2. Operator and Visual Observer

i. Operator

ii. Visual Observer

3. See-and-Avoid and Visibility Requirements

i. See-and-Avoid

ii. Additional Visibility Requirements

iii. Yielding Right of Way

4. Containment and Loss of Positive Control

i. Confined Area of Operation Boundaries

ii. Mitigating Loss-of-Positive-Control Risk

5. Limitations on Operations in Certain Airspace

i. Controlled Airspace

ii. Prohibited or Restricted Areas

iii. Areas Designated by Notice to Airmen

6. Airworthiness, Inspection, Maintenance, and Airworthiness Directives

i. Inspections and Maintenance

ii. Airworthiness Directives

7. Miscellaneous Operating Provisions

i. Careless or Reckless Operation

ii. Drug and Alcohol Prohibition

iii. Medical Conditions

iv. Sufficient Power for the Small UAS

v. Registration and Marking

E. Operator Certificate

1. Applicability

2. Unmanned Aircraft Operator Certificate—Eligibility & Issuance

i. Minimum Age

ii. English Language Proficiency

iii. Pilot Qualification

a. Flight Proficiency and Aeronautical Experience

b. Initial Aeronautical Knowledge Test

c. Areas of Knowledge Tested on the Initial Knowledge Test

d. Administration of the Initial Knowledge Test

e. Recurrent Aeronautical Knowledge Test

i. General Requirement and Administration of the Recurrent Knowledge Test

ii. Recurrent Test Areas of Knowledge

iv. Issuance of an Unmanned Aircraft Operator Certificate With Small UAS Rating

v. Not Requiring an Airman Medical Certificate

4. Military Equivalency

5. Unmanned Aircraft Operator Certificate: Denial, Revocation, Suspension, Amendment, and Surrender

i. Transportation Security Administration Vetting and Positive Identification

ii. Drugs and Alcohol Violations

iii. Change of Name

iv. Change of Address

v. Voluntary Surrender of Certificate

F. Registration

G. Marking

1. Display of Registration Number

2. Marking of Products and Articles

H. Fraud and False Statements

I. Oversight

1. Inspection, Testing, and Demonstration of Compliance

2. Accident Reporting

J. Section 333 Statutory Findings

1. Hazard to Users of the NAS or the Public

2. National Security

3. Airworthiness Certification

IV. Regulatory Notices and Analyses

A. Regulatory Evaluation

1. Total Benefits and Costs of This Rule

2. Who is potentially affected by this Rule?

4. Benefit Summary

5. Cost Summary

B. Initial Regulatory Flexibility Determination (IRFA)

1. Description of Reasons the Agency Is Considering the Action

2. Statement of the Legal Basis and Objectives for the Proposed Rule

3. Description of the Recordkeeping and Other Compliance Requirements of the Proposed Rule

4. All Federal Rules That May Duplicate, Overlap, or Conflict With the Proposed Rule

5. Description and an Estimated Number of Small Entities To Which the Proposed Rule Will Apply

6. Alternatives Considered

C. International Trade Impact Assessment

D. Unfunded Mandates Assessment

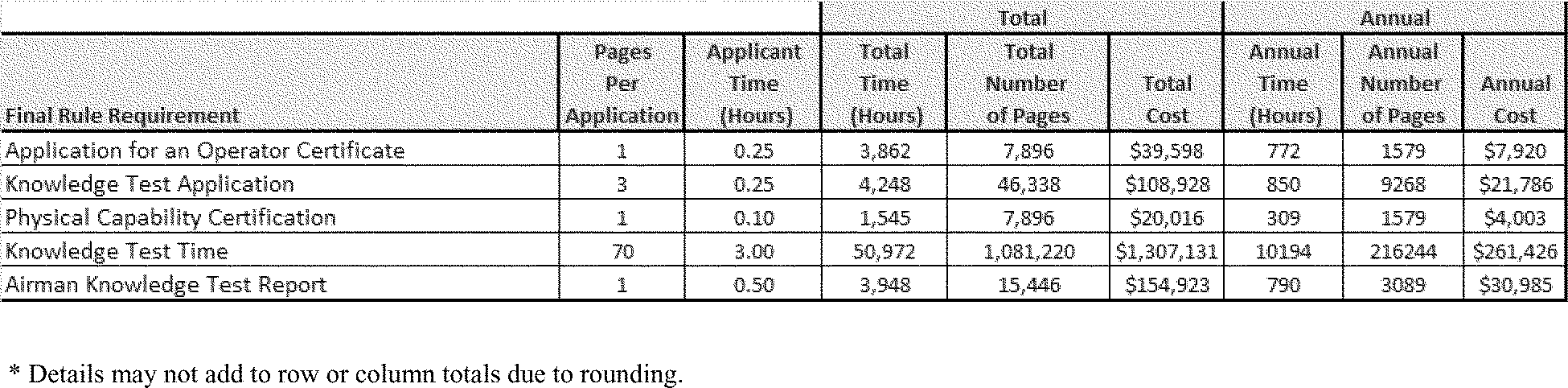

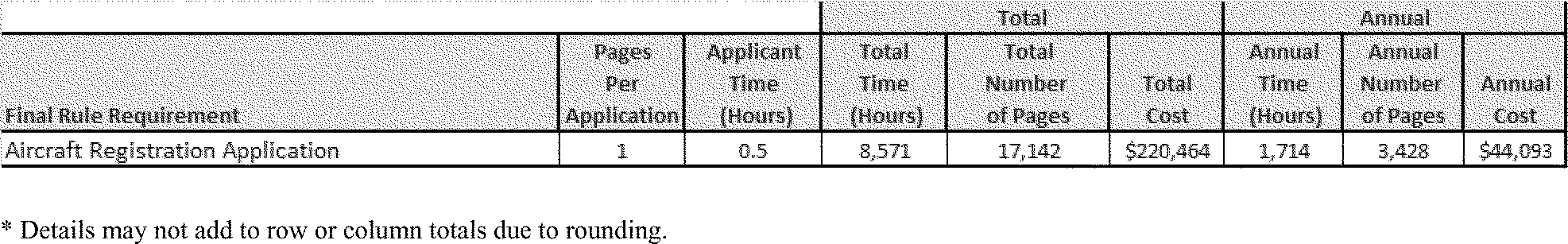

E. Paperwork Reduction Act

1. Obtaining an Unmanned Aircraft Operator Certificate With a Small UAS Rating

2. Registering a Small Unmanned Aircraft

3. Accident Reporting

F. International Compatibility and Cooperation

G. Environmental Analysis

H. Regulations Affecting Intrastate Aviation in Alaska

V. Executive Order Determinations

A. Executive Order 13132, Federalism

B. Executive Order 13211, Regulations That Significantly Affect Energy Supply, Distribution, or Use

VI. Additional Information

A. Comments Invited

B. Availability of Rulemaking Documents

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose of the Regulatory Action

This rulemaking proposes operating requirements to allow small unmanned aircraft systems (small UAS) to operate for non-hobby or non-recreational purposes. A small UAS consists of a small unmanned aircraft (which, as defined by statute, is an unmanned aircraft weighing less than 55 pounds [3] ) and equipment necessary for the safe and efficient operation of that aircraft. The FAA has accommodated non-recreational small UAS use through various mechanisms, such as special airworthiness certificates, exemptions, and certificates of waiver or authorization (COA). This proposed rule would be the next phase of integrating small UAS into the NAS.

The following are examples of possible small UAS operations that could be conducted under this proposed framework:

- Crop monitoring/inspection;

- Research and development;

- Educational/academic uses;

- Power-line/pipeline inspection in hilly or mountainous terrain;

- Antenna inspections;

- Aiding certain rescue operations such as locating snow avalanche victims;

- Bridge inspections;

- Aerial photography; and

- Wildlife nesting area evaluations.

Because of the potential societally beneficial applications of small UAS, the FAA has been seeking to incorporate the operation of these systems into the national airspace system (NAS) since 2008. In April 2008, the FAA chartered the small UAS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC). In April 2009, the ARC provided the FAA with recommendations on how small UAS could be safely integrated into the NAS. Since that time, the FAA has been working on a rulemaking to incorporate small UAS operations into the NAS.

In 2012, Congress passed the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (Pub. L. 112-95). Section 333 of Public Law 112-95 directed the Secretary to determine whether UAS operations posing the least amount of public risk and no threat to national security could safely be operated in the NAS and if so, to establish requirements for the safe operation of these systems in the NAS, prior to completion of the UAS comprehensive plan and rulemakings required by section 332 of Public Law 112-95. As part of its ongoing efforts to integrate UAS operations in the NAS in accordance with section 332, and as authorized by section 333 of Public Law 112-95, the FAA is proposing to amend its regulations to adopt specific rules for the operation of small UAS in the NAS.

Based on our experience with the certification, exemption, and COA process, the FAA has developed the framework proposed in this rule to enable certain small UAS operations to commence upon adoption of the final rule and accommodate technologies as they evolve and mature. This proposed framework would allow small UAS operations for many different non-recreational purposes, such as the ones discussed previously, without requiring airworthiness certification, exemption, or a COA.Start Printed Page 9546

B. Summary of the Major Provisions of the Regulatory Action

Specifically, the FAA is proposing to add a new part 107 to Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) to allow for routine civil operation of small UAS in the NAS and to provide safety rules for those operations. Consistent with the statutory definition, the proposed rule defines small UAS as those UAS weighing less than 55 pounds. To mitigate risk, the proposed rule would limit small UAS to daylight-only operations, confined areas of operation, and visual-line-of-sight operations. This proposed rule also addresses aircraft registration and marking, NAS operations, operator certification, visual observer requirements, and operational limits in order to maintain the safety of the NAS and ensure that they do not pose a threat to national security. Below is a summary of the major provisions of the proposed rule.

Summary of Major Provisions of Proposed Part 107

Operational Limitations • Unmanned aircraft must weigh less than 55 lbs. (25 kg). • Visual line-of-sight (VLOS) only; the unmanned aircraft must remain within VLOS of the operator or visual observer. • At all times the small unmanned aircraft must remain close enough to the operator for the operator to be capable of seeing the aircraft with vision unaided by any device other than corrective lenses. • Small unmanned aircraft may not operate over any persons not directly involved in the operation. • Daylight-only operations (official sunrise to official sunset, local time). • Must yield right-of-way to other aircraft, manned or unmanned. • May use visual observer (VO) but not required. • First-person view camera cannot satisfy “see-and-avoid” requirement but can be used as long as requirement is satisfied in other ways. • Maximum airspeed of 100 mph (87 knots). • Maximum altitude of 500 feet above ground level. • Minimum weather visibility of 3 miles from control station. • No operations are allowed in Class A (18,000 feet & above) airspace. • Operations in Class B, C, D and E airspace are allowed with the required ATC permission. • Operations in Class G airspace are allowed without ATC permission • No person may act as an operator or VO for more than one unmanned aircraft operation at one time. • No operations from a moving vehicle or aircraft, except from a watercraft on the water. • No careless or reckless operations. • Requires preflight inspection by the operator. • A person may not operate a small unmanned aircraft if he or she knows or has reason to know of any physical or mental condition that would interfere with the safe operation of a small UAS. • Proposes a microUAS category that would allow operations in Class G airspace, over people not involved in the operation, and would require airman to self-certify that they are familiar with the aeronautical knowledge testing areas. Operator Certification and Responsibilities • Pilots of a small UAS would be considered “operators”. • Operators would be required to: ○ Pass an initial aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved knowledge testing center. ○ Be vetted by the Transportation Security Administration. ○ Obtain an unmanned aircraft operator certificate with a small UAS rating (like existing pilot airman certificates, never expires). ○ Pass a recurrent aeronautical knowledge test every 24 months. ○ Be at least 17 years old. ○ Make available to the FAA, upon request, the small UAS for inspection or testing, and any associated documents/records required to be kept under the proposed rule. ○ Report an accident to the FAA within 10 days of any operation that results in injury or property damage. ○ Conduct a preflight inspection, to include specific aircraft and control station systems checks, to ensure the small UAS is safe for operation. Aircraft Requirements • FAA airworthiness certification not required. However, operator must maintain a small UAS in condition for safe operation and prior to flight must inspect the UAS to ensure that it is in a condition for safe operation. Aircraft Registration required (same requirements that apply to all other aircraft). • Aircraft markings required (same requirements that apply to all other aircraft). If aircraft is too small to display markings in standard size, then the aircraft simply needs to display markings in the largest practicable manner. Model Aircraft • Proposed rule would not apply to model aircraft that satisfy all of the criteria specified in section 336 of Public Law 112-95. • The proposed rule would codify the FAA's enforcement authority in part 101 by prohibiting model aircraft operators from endangering the safety of the NAS. Operator Certification: Under the proposed rule, the person who manipulates the flight controls of a small UAS would be defined as an “operator.” A small UAS operator would be required to pass an aeronautical knowledge test and obtain an unmanned aircraft operator certificate with a small UAS rating from the FAA before operating a small UAS. In order to maintain his or her operator certification, the operator would be Start Printed Page 9547required to pass recurrent knowledge tests every 24 months subsequent to the initial knowledge test. These tests would be created by the FAA and administered by FAA-approved knowledge testing centers. Although a specific distant vision acuity standard is not being proposed, this proposed rule would require the operator to keep the small unmanned aircraft close enough to the control station to be capable of seeing that aircraft through his or her unaided (except for glasses or contact lenses) visual line of sight. The operator would also be required to actually maintain visual line of sight of the small unmanned aircraft if a visual observer is not used.

Visual Observer: Under the proposed rule, an operator would not be required to work with a visual observer, but a visual observer could be used to assist the operator with the proposed visual-line-of-sight and see-and-avoid requirements by maintaining constant visual contact with the small unmanned aircraft in place of the operator. While an operator would always be required to have the capability for visual line of sight of the small unmanned aircraft, this proposed rule would not require the operator to exercise this capability if he or she is augmented by at least one visual observer. No certification requirements are being proposed for visual observers. A small UAS operation would not be limited in the number of visual observers involved in the operation, but the operator and visual observer(s) must remain situated such that the operator and any visual observer(s) are all able to view the aircraft at any given time. The operator and visual observer(s) would be permitted to communicate by radio or other communication-assisting device, so they would not need to remain in close enough physical proximity to allow for unassisted oral communication.

Since the operator and any visual observers would be required to be in a position to maintain or achieve visual line of sight with the aircraft at all times, the proposed rule would effectively prohibit a relay or “daisy-chain” formation of multiple visual observers by requiring that the operator must always be capable of seeing the small unmanned aircraft. Such arrangements would potentially expand the area of a small UAS operation and pose an increased public risk if there is a loss of aircraft control.

Operational Scope: A small UAS operator would be required to see and avoid all other users of the NAS in the area in which the small UAS is operating. The proposed rule contains operating restrictions designed to help ensure that the operator is able to yield right-of-way to other aircraft at all times.

The proposed rule would limit the exposure of small unmanned aircraft to other users of the NAS by restricting small UAS operations in controlled airspace. Specifically, small UAS would be prohibited from operating in Class A airspace, and would require prior permission from Air Traffic Control to operate in Class B, C, or D airspace, or within the lateral boundaries of the surface area of Class E airspace designated for an airport. The risk of collision with other aircraft would be further reduced by limiting small UAS operations to a maximum airspeed of 87 knots (100 mph) and a maximum altitude of 500 feet above ground.

Further, in order to enable maximum visibility for small UAS operation, the proposed rule would restrict small UAS to daylight-only operations (sunrise to sunset), and impose a minimum weather-visibility of 3 statute miles (5 kilometers) from the small UAS control station.

Aircraft Maintenance: Under the proposed rule, the operator of a small UAS would be required to conduct a preflight inspection before each flight operation, and determine that the small UAS (aircraft, control station, launch and recovery equipment, etc.) is safe for operation.

Airworthiness: Pursuant to section 333(b)(2) of Public Law 112-95, the Secretary has determined that small UAS subject to this proposed rule would not require airworthiness certification because the safety concerns associated with small UAS operation would be mitigated by the other provisions of this proposed rule. Rather, this proposed rule would require the operator to ensure that the small UAS is in a condition for safe operation by conducting an inspection prior to each flight.

Registration and Marking: This proposed rule would apply to small unmanned aircraft the current registration requirements that apply to all aircraft. Once a small unmanned aircraft is registered, this proposed rule would require that aircraft to display its registration marking in a manner similar to what is currently required of all aircraft.

C. Costs and Benefits

This proposed rule reflects the fact that technological advances in small UAS have led to a developing commercial market for their uses by providing a safe operating environment for them and for other aircraft in the NAS. In time, the FAA anticipates that the proposed rule would provide an opportunity to substitute small UAS operations for some higher risk manned flights, such as inspecting towers, bridges, or other structures. The use of small unmanned aircraft would avert potential fatalities and injuries to those in the aircraft and on the ground. It would also lead to more efficient methods of performing certain commercial tasks that are currently performed by other methods. The FAA has not quantified the benefits for this proposed rulemaking because we lack sufficient data. The FAA invites commenters to provide data that could be used to quantify the benefits of this proposed rule.

For any commercial operation occurring because this rule is enacted, the operator/owner of that small UAS will have determined the expected revenue stream of the flights exceeds the cost of the flights operation. In each such case this rule helps enable new markets to develop.

The costs are shown in the table below.

Total and Present Value Cost Summary by Provision

[Thousands of current year dollars]

Type of cost Total costs (000) 7% P.V. (000) Applicant/small UAS operator: Travel Expense $151.7 $125.9 Knowledge Test Fees 2,548.6 2,114.2 Positive Identification of the Applicant Fee 434.3 383.7 Owner: Small UAS Registration Fee 85.7 70.0 Time Resource Opportunity Costs: Start Printed Page 9548 Applicants Travel Time 296.1 245.3 Knowledge Test Application 108.9 90.2 Physical Capability Certification 20.0 17.7 Knowledge Test Time 1,307.1 1,082.9 Small UAS Registration Form 220.5 179.7 Change of Name or Address Form 14.9 12.3 Knowledge Test Report 154.9 128.5 Pre-flight Inspection Not quantified Accident Reporting Minimal cost Government Costs: TSA Security Vetting 1,026.5 906.9 FAA—sUAS Operating Certificate 39.6 35.0 FAA—Registration 394.3 321.8 Total Costs 6,803.1 5,714.0 * Details may not add to row or column totals due to rounding. II. Background

This NPRM addresses the operation, airman certification, and registration of civil small UAS.

A small UAS consists of a small unmanned aircraft and associated elements that are necessary for the safe and efficient operation of that aircraft in the NAS. Associated elements that are necessary for the safe and efficient operation of the aircraft include the interface that is used to control the small unmanned aircraft (known as a control station) and communication links between the control station and the small unmanned aircraft. A small unmanned aircraft is defined by statute as “an unmanned aircraft weighing less than 55 pounds.” [4] Due to the size of a small unmanned aircraft, the FAA envisions considerable potential business and non-business applications, particularly in areas that are hard to reach for a manned aircraft.

The following are examples of possible small UAS operations that could be conducted under this proposed framework:

- Crop monitoring/inspection;

- Research and development;

- Educational/academic uses;

- Power-line/pipeline inspection in hilly or mountainous terrain;

- Antenna inspections;

- Aiding certain rescue operations such as locating snow avalanche victims;

- Bridge inspections;

- Aerial photography; and

- Wildlife nesting area evaluations.

The following sections discuss: (1) The public risk associated with small UAS operations; (2) the current legal framework governing small UAS operations; and (3) the FAA's ongoing efforts to incorporate small UAS operations into the NAS.

A. Analysis of Public Risk Posed by Small UAS Operations

Small UAS operations pose risk considerations that are different from the risk considerations associated with manned-aircraft operations. On one hand, certain operations of a small unmanned aircraft, discussed more fully in section III.D of this preamble, have the potential to pose significantly less risk to persons and property than comparable operations of a manned aircraft. The typical total takeoff weight of a general aviation aircraft is between 1,300 and 6,000 pounds. By contrast, the total takeoff weight of a small unmanned aircraft is less than 55 pounds. Consequently, because a small unmanned aircraft is significantly lighter than a manned aircraft, in the event of a mishap, the small unmanned aircraft would pose significantly less risk to persons and property on the ground. As such, a small UAS operation whose parameters are well defined so it does not pose a significant risk to other aircraft would also pose a smaller overall public risk or threat to national security than the operation of a manned aircraft.

However, even though small UAS operations have the potential to pose a lower level of public risk in certain types of operations, the unmanned nature of the small UAS operations raises two unique safety concerns that are not present in manned-aircraft operations. The first safety concern is whether the person operating the small unmanned aircraft, who would be physically separated from that aircraft during flight, would have the ability to see manned aircraft in the air in time to prevent a mid-air collision between the small unmanned aircraft and another aircraft. As discussed in more detail below, the FAA's regulations currently require each person operating an aircraft to maintain vigilance “so as to see and avoid other aircraft.” [5] This is one of the fundamental principles for collision avoidance in the NAS.

For manned-aircraft operations, “see and avoid” is the responsibility of persons on board an aircraft. By contrast, small unmanned aircraft operations have no human beings physically on the unmanned aircraft with the same visual perspective and the ability to see other aircraft in the manner of a manned-aircraft pilot. Thus, the challenge for small unmanned aircraft operations is to ensure that the person operating the small unmanned aircraft is able to see and avoid other aircraft.

In considering this issue, the FAA examined to what extent existing technology could provide a solution to this problem. The FAA notes that advances in technologies that use ground-based radar and aircraft sensors to detect the reply signals from aircraft ATC transponders have provided significant improvement in the ability to detect other aircraft in close proximity to each other. The Traffic Collision Avoidance System also has the ability to provide guidance to flight crews to maneuver appropriately to avoid a mid-air collision. Both of these technologies have done an excellent job in reducing the mid-air collision rate between manned aircraft. Unfortunately, the equipment required to utilize these widely available technologies is Start Printed Page 9549currently too large and heavy to be used in small UAS operations. Until this equipment is miniaturized to the extent necessary to make it viable for use in small UAS operations, existing technology does not appear to provide a way to resolve the “see and avoid” problem with small UAS operations without maintaining human visual contact with the small unmanned aircraft during flight.

The second safety concern with small UAS operations is the possibility that, during flight, the person operating the small UAS may become unable to use the control interface to operate the small unmanned aircraft due to a failure of the control link between the aircraft and the operator's control station. This is known as a loss of positive control. This situation may result from a system failure or because the aircraft has been flown beyond the signal range or in an area where control link communication between the aircraft and the control station is interrupted. A small unmanned aircraft whose flight is unable to be directly controlled could pose a significant risk to persons, property, or other aircraft.

B. Current Statutory and Regulatory Structure Governing Small UAS

Due to the lack of an onboard pilot, small unmanned aircraft are unable to see and avoid other aircraft in the NAS. Therefore, small UAS operations conflict with the FAA's current operating regulations codified in 14 CFR part 91 that apply to general aviation. Specifically, at the heart of the part 91 operating regulations is § 91.113(b), which requires each person operating an aircraft to maintain vigilance “so as to see and avoid other aircraft.”

The FAA created this requirement in a 1968 rulemaking that combined two previous aviation regulatory provisions, Civil Air Regulations (CAR) §§ 60.13(c) and 60.30.[6] Both of the provisions that were combined to create the “see and avoid” requirement of § 91.113(b) were intended to address aircraft collision-awareness problems by requiring that a pilot on board the aircraft look out of the aircraft during flight to observe whether other aircraft are on a collision path with his or her aircraft. Those provisions did not contemplate the use of technology to substitute for the human vision of a pilot on board the aircraft. Similarly, there is no evidence that those provisions contemplated a pilot fulfilling his or her “see and avoid” responsibilities from outside the aircraft. To the contrary, CAR section 60.13(c) stated that one of the problems it intended to address was “preoccupation by the pilot with cockpit duties,” which indicates that the regulation contemplated the presence of a pilot on board the aircraft.

Because the regulations that resulted in the see-and-avoid requirement of § 91.113(b) did not contemplate that this requirement could be complied with by a pilot who is outside the aircraft, § 91.113(b) currently requires an aircraft pilot to have the perspective of being inside the aircraft as that aircraft is moving in order to see and avoid other aircraft. Since the operator of a small UAS does not have this perspective, operation of a small UAS could not meet the see and avoid requirement of § 91.113(b) at this time.

In addition to currently being prohibited by § 91.113(b), there are also statutory considerations that apply to small UAS operations. Specifically, even though a small UAS is different from a manned aircraft, the operation of a small UAS still involves the operation of an aircraft. This is because the FAA's statute defines an “aircraft” as “any contrivance invented, used, or designed to navigate or fly in the air.” 49 U.S.C. 40102(a)(6). Since a small unmanned aircraft is a contrivance that is invented, used, and designed to fly in the air, a small unmanned aircraft is an aircraft for purposes of the FAA's statutes.[7]

Because a small UAS involves the operation of an “aircraft,” this triggers the FAA's registration and certification statutory requirements. Specifically, subject to certain exceptions, a person may not operate a civil aircraft that is not registered. 49 U.S.C. 44101(a). In addition, a person may not operate a civil aircraft in air commerce without an airworthiness certificate. 49 U.S.C. 44711(a)(1). Finally, a person may not serve in any capacity as an airman on a civil aircraft being operated in air commerce without an airman certificate. 49 U.S.C. 44711(a)(2)(A).[8]

The term “air commerce,” as used in the FAA's statutes, is defined broadly to include “the operation of aircraft within the limits of a Federal airway, or the operation of aircraft that directly affects, or may endanger safety in foreign or interstate air commerce.” 49 U.S.C. 40102(a)(3). Because of this broad definition, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has held that “any use of an aircraft, for purpose of flight, constitutes air commerce.” [9] Courts that have considered this issue have reached similar conclusions that “air commerce,” as defined in the FAA's statute, encompasses a broad range of commercial and non-commercial aircraft operations.[10]

Accordingly, because “air commerce” encompasses such a broad range of aircraft operations, a civil small unmanned aircraft cannot currently be operated, for purposes of flight, if: (1) It is not registered (49 U.S.C. 44101(a)); (2) it does not possess an airworthiness certificate (49 U.S.C. 44711(a)(1)); and (3) the airman operating the aircraft does not possess an airman certificate (49 U.S.C. 44711(a)(2)(A)). However, the FAA's current processes for issuing airworthiness and airman certificates were designed to be used for manned aircraft and do not take into account the considerations associated with civil small UAS.

Specifically, obtaining a type certificate and a standard airworthiness certificate, which permits the widest range of aircraft operation, currently takes about 3 to 5 years. Because the pertinent existing regulations do not differentiate between manned and unmanned aircraft, a small UAS is currently subject to the same airworthiness certification process as a manned aircraft. However, it is not practically feasible for many small UAS manufacturers to go through the certification process required of manned aircraft. This is because small UAS technology is rapidly evolving at this time, and consequently, if a small UAS manufacturer goes through a 3-to-5-year process to obtain a type certificate, which enables the issuance of a standard airworthiness certificate, the small UAS would be technologically outdated by the time it completed the certification process. For example, advances in lightweight battery technology may allow new lightweight transponders and power sources within the next 3 to 5 years that are currently unavailable for small UAS operations.

The FAA notes that there are several other certification options available to Start Printed Page 9550small UAS manufacturers and operators who do not wish to go through the process of obtaining a type certificate and standard airworthiness certificate. However, because each of these options has significant limitations, these options do not provide flexibility for most routine small UAS operations. These certification options are as follows:

- A special airworthiness certificate in the experimental category may be issued to UAS pursuant to 14 CFR 21.191-21.195. This certificate is time-limited, and cannot be used for any activities other than research and development, market surveys, and crew training.

- A special flight permit may be issued pursuant to 14 CFR 21.197. At this time, however, a special flight permit for a UAS is limited to production flight testing of new production aircraft.[11]

- A special airworthiness certificate in the restricted category is issued pursuant to 14 CFR 21.25(a). There are two options for obtaining this certificate.

First, pursuant to § 21.25(a)(2), a certificate may be issued for aircraft accepted by an Armed Force of the United States and later modified for a special purpose.

Second, pursuant to § 21.25(a)(1), a certificate may be issued for aircraft used in special purpose operations, which consist of:

(1) agricultural operations;

(2) forest and wildlife conservation;

(3) aerial surveying;

(4) patrolling (pipelines, power lines, and canals);

(5) weather control;

(6) aerial advertising; and

(7) any other operation specified by the FAA.

As can be seen from the above list, the current certification options are limited to very specific purposes. Accordingly, they do not provide sufficient flexibility for most routine civil small UAS operations within the NAS.

In addition to obtaining an airworthiness certificate, any person serving as an airman in the operation of a small UAS must obtain an airman certificate. 49 U.S.C. 44711(a)(2)(A). The statute defines an “airman” to include an individual who is “in command, or as pilot, mechanic, or member of the crew, who navigates aircraft when under way.” 49 U.S.C. 40102(a)(8)(A). Because the person operating the small UAS is in command and is a member of the crew who navigates the aircraft, that person is an airman and must obtain an airman certificate.

Under current pilot certification regulations, depending on the type of operation, the operator of the small UAS currently must obtain either a private pilot certificate or a commercial pilot certificate. A private pilot certificate cannot be used to operate a small UAS for compensation or hire unless the flight is only incidental to the operator's business or employment.[12] Typically, to obtain a private pilot certificate, the small UAS operator currently has to: (1) Receive training in specific aeronautical knowledge areas; (2) receive training from an authorized instructor on specific areas of aircraft operation; (3) obtain a minimum of 40 hours of flight experience; and (4) obtain a third-class airman medical certificate.[13] Conversely, holding at least a commercial pilot certificate allows the small UAS to generally be used for compensation or hire, but is more difficult to obtain. In addition to the requirements necessary to obtain a private pilot certificate, applicants for a commercial pilot certificate currently need to also obtain 250 hours of flight time, satisfy extensive testing requirements, and obtain a second-class airman medical certificate.[14]

While these airman certification requirements are necessary for manned aircraft operations, they impose an unnecessary burden for many small UAS operations. This is because a person typically obtains a private or commercial pilot certificate by learning how to operate a manned aircraft. Much of that knowledge would not be applicable to small UAS operations because a small UAS is operated differently than a manned aircraft. In addition, the knowledge currently necessary to obtain a private or commercial pilot certificate would not equip the certificate holder with the tools necessary to safely operate a small UAS. Specifically, applicants for a private or commercial pilot certificate currently are not trained in how to deal with the “see-and-avoid” and loss-of-positive-control safety issues that are unique to small unmanned aircraft. Thus, requiring persons wishing to operate a small UAS to obtain a private or commercial pilot certificate imposes the cost of certification on those persons, but does not result in a significant safety benefit because the process of obtaining the certificate does not equip those persons with the tools necessary to mitigate the public risk posed by small UAS operations.

Recognizing the problem of applying the operating rules of part 91 to small UAS operations and the cost imposed on small UAS operations by existing certification processes, the FAA fashioned a temporary solution. Specifically, the FAA issued an advisory circular (AC) 91-57 and a policy statement elaborating on AC 91-57, which provide guidance for the safe operation of “model aircraft.” The policy statement defines a “model aircraft” as a UAS that is used for hobby or recreational purposes.[15] The policy statement explains that AC 91-57:

[E]ncourages good judgment on the part of operators so that persons on the ground or other aircraft in flight will not be endangered. The AC contains among other things, guidance for site selection. Users are advised to avoid noise sensitive areas such as parks, schools, hospitals, and churches. Hobbyists are advised not to fly in the vicinity of spectators until they are confident that the model aircraft has been flight tested and proven airworthy. Model aircraft should be flown below 400 feet above the surface to avoid other aircraft in flight. The FAA expects that hobbyists will operate these recreational model aircraft within visual line-of-sight.[16]

Neither AC 91-57 nor the associated policy statement contains any registration or certification requirements.[17]

To date, the FAA has used its discretion[18] to not bring enforcement action against model-aircraft operations that comply with AC 91-57. However, the use of discretion to permit continuing violation of FAA statutes and regulations is not a viable long-term solution for incorporating UAS operations into the NAS. Additionally, because AC 91-57 and the associated policy statement are limited to model aircraft, they do not apply to non-recreational UAS operations. Thus, even with the use of enforcement discretion, because of the difficulty of obtaining the Start Printed Page 9551requisite certification for a small UAS and because operation of a small UAS would violate the see-and-avoid requirement of § 91.113(b), non-recreational civil small UAS operations are effectively prohibited at this time.

C. Integrating Small UAS Operations Into the NAS

To address the issues discussed above, the FAA chartered the small UAS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) on April 10, 2008. On April 1, 2009, the ARC provided the FAA with recommendations on how small UAS could be safely integrated into the NAS.[19] In 2013, the U.S. Department of Transportation issued a comprehensive plan and subsequently the FAA issued a roadmap of its efforts to achieve safe integration of UAS operations into the NAS.[20]

In 2012, Congress passed the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (Pub. L. 112-95). In section 332(b) of Public Law 112-95, Congress directed the Secretary to issue a final rule on small unmanned aircraft systems that will allow for civil operations of such systems in the NAS.[21] In section 333 of Public Law 112-95, Congress also directed the Secretary to determine whether “certain unmanned aircraft systems may operate safely in the national airspace system.” To make a determination under section 333, we must assess “which types of unmanned aircraft systems, if any, as a result of their size, weight, speed, operational capability, proximity to airports and populated areas, and operation within visual line of sight do not create a hazard to users of the national airspace system or the public or pose a threat to national security.” Public Law 112-95, Sec. 333(b)(1). The Secretary must also determine whether a certificate of waiver or authorization, or airworthiness certification is necessary to mitigate the public risk posed by the unmanned aircraft systems that are under consideration. Public Law 112-95, Sec. 333(b)(2). If the Secretary determines that certain unmanned aircraft systems may operate safely in the NAS, then the Secretary must “establish requirements for the safe operation of such aircraft systems in the national airspace system.” Public Law 112-95, Sec. 333(c). The flexibility provided for in section 333 did not extend to airman certification and security vetting, aircraft marking, or registration requirements.

As noted above, section 333(b)(2) provided the Secretary of Transportation with discretionary power as to whether airworthiness certification should be required for certain small UAS.[22] As discussed previously, the FAA's statute normally requires an aircraft being flown outdoors to possess an airworthiness certificate.[23] However, subsection 333(b)(2) allows for the determination that airworthiness certification is not necessary for certain small UAS. The key determinations that must be made in order for UAS to operate under the authority of section 333 are: (1) The operation must not create a hazard to users of the national airspace system or the public; and (2) the operation must not pose a threat to national security.[24] In making these determinations, we must consider the following factors: Size, weight, speed, operational capability, proximity to airports and populated areas, and operation within visual line of sight. Of these factors, operation within visual line of sight is a primary factor for evaluation. At this point in time, we have determined that technology has not matured to the extent that would allow small UAS to be used safely in lieu of visual line of sight without creating a hazard to other users of the NAS or the public, or posing a threat to national security.

This construction of section 333 is a reasonable interpretation that is consistent with the statutory text and reflects Congressional intent in adopting the provision. We invite comments on whether there are well-defined circumstances and conditions under which operation beyond the line of sight would pose little or no additional risk to other users of the NAS, the public, or national security. Finally, we invite comments on the technologies and operational capabilities or procedures needed to allow UAS flights beyond visual line of sight, and how such technologies, capabilities and procedures could be accommodated under this rule or in a future rulemaking.

As a result of its ongoing integration efforts, the FAA seeks to change its regulations to take the first step in the process of integrating small UAS operations into the NAS. This proposal would utilize the airworthiness-certification flexibility provided by Congress in section 333 of Public Law 112-95, and allow some small UAS operations to commence in the NAS.[25]

In addition, to further facilitate the integration of UAS into the NAS, the FAA has selected six test sites to test UAS technology and operations. As of August 2014, all of the UAS test sites, which were selected based on geographic and climatic diversity, are operational and will remain in place for the next 5 years to help us gather operational data to foster further integration, as well as evaluate new technologies. In addition, the FAA is in the process of selecting a new UAS Center of Excellence which will also serve as another resource for these activities. The FAA invites comments on how it can improve or further leverage its test site program to encourage innovation, safe development and UAS integration into the NAS.

III. Discussion of the Proposal

As discussed in the previous section, in order to determine whether certain UAS may operate safely in the NAS pursuant to section 333, the Secretary must find that the operation of the UAS would not: (1) Create a hazard to users of the NAS or the public; or (2) pose a threat to national security. The Secretary must also determine whether small UAS operations subject to this proposed rule pose a safety risk sufficient to require airworthiness certification. The following preamble sections discuss the specific components of this proposed rule, and in section III.J below, we explain how these components work together and allow the Secretary to make the statutory findings required by section 333.

A. Incremental Approach and Privacy

The FAA began its small UAS rulemaking in 2005. In its initial approach to this rulemaking, which the FAA utilized from 2005 until November 2013, the FAA attempted to implement the ARC's recommendations and craft a rule that encompassed the widest possible range of small UAS operations. This approach utilized a regulatory structure similar to the one that the FAA uses for manned aircraft. Specifically, small UAS operations that pose a low risk to people, property, and other Start Printed Page 9552aircraft would have been subject to less stringent regulation while small UAS operations posing a greater risk would have been subject to more stringent regulation in order to mitigate the greater risk.

In exploring this approach, the FAA found that, as discussed previously, there are two unique safety issues associated with UAS: (1) Extending “see and avoid” anti-collision principles to a pilot that is not physically present on the aircraft; and (2) loss of positive control of the unmanned aircraft. In addition, at the time that it was considering this approach, the FAA did not have the discretion necessary to exempt these aircraft from the statutory requirement for airworthiness certification, as the section 333 authority did not come into effect until February 14, 2012. As a result of these issues, the FAA's original broadly-scoped approach to the rulemaking effort took significantly longer than anticipated. Consequently, the FAA decided to proceed with multiple incremental UAS rules rather than a single omnibus rulemaking in order to utilize the flexibility with regard to airworthiness certification that Congress provided in section 333.

Accordingly, at this time, the FAA is proposing a rule that, pursuant to section 333 of Public Law 112-95, will integrate small UAS operations posing the least amount of risk. Because these operations pose the least amount of risk, this proposed rule would treat the entire spectrum of operations that would be subject to this rule in a similar manner by imposing less stringent regulatory burdens that would ensure that the safety and security of the NAS would not be reduced by operation of these UAS. In the meantime, the FAA will continue working on integrating UAS operations that pose greater amounts of risk, and will issue notices of proposed rulemaking for those operations once the pertinent issues have been addressed, consistent with the approach set forth in the UAS Comprehensive Plan for Integration and FAA roadmap for integration.[26] Once the entire integration process is complete, the FAA envisions the NAS populated with UAS that operate well beyond the operational limits proposed in this rule. Those UAS will be regulated differently than the UAS that would be integrated through this rule, and will be addressed in subsequent rulemakings. The FAA has selected this approach because it would allow lower-risk small UAS operations to be incorporated into the NAS immediately instead of waiting until the issues associated with higher-risk UAS operations are resolved.

The approach of this proposal is meant to address low risk operations; to the greatest extent possible, it takes a data-driven, risk-based approach to defining specific regulatory requirements for small UAS operations. It is well understood that regulations that are articulated in terms of the desired outcomes (i.e., “performance standards”) are generally preferable to those that specify the means to achieve the desired outcomes (i.e., “design” standards). According to Office of Management and Budget Circular A-4 (“Regulatory Analysis”), performance standards “give the regulated parties the flexibility to achieve the regulatory objectives in the most cost-effective way.” [27]

Design standards have a tendency to lock in certain approaches that limit the incentives to innovate and may effectively prohibit new technologies altogether. The distinction between design and performance standards is particularly important where technology is evolving rapidly, as is the case with small UAS.

In this proposal, the regulatory objectives are to enable integration of small UAS into the NAS in a manner that does not impose unacceptable risk to other aircraft, people, or property. The FAA seeks comment on whether there are additional requirements that could be specified in ways that are more performance-oriented in order to minimize any disincentives to develop new technologies that achieve the regulatory objectives at lower cost.

Recently, the FAA, with the approval of the Secretary, has been issuing exemptions in accordance with 14 CFR part 11 and section 333 of Public Law 112-95 to accommodate an increasing number of small UAS operations that are not for hobby or recreational purposes. If adopted, this rule will eliminate the need for the vast majority of these exemptions. The exemption process will continue to be available for UAS operations that fall outside the parameters of this rule. Such operations may involve the use of more advanced technologies that are not yet mature at the time of this rulemaking.

The FAA also notes that, because UAS-associated technologies are rapidly evolving at this time, new technologies could come into existence after this rule is issued or existing technologies may evolve to the extent that they establish a level of reliability sufficient to allow those technologies to be relied on for risk mitigation. These technologies may alleviate some of the risk concerns that underlie the provisions of this rulemaking like the line of sight rule. Accordingly, the FAA invites comments as to whether the final rule should relax operating restrictions on small UAS equipped with technology that addresses the concerns underlying the operating limitations of this proposed rule, for instance through some type of deviation authority (such as a letter of authorization or a waiver).

The FAA also notes that privacy concerns have been raised about unmanned aircraft operations. Although these issues are beyond the scope of this rulemaking, recognizing the potential implications for privacy and civil rights and civil liberties from the use of this technology, and consistent with the direction set forth in the Presidential Memorandum, Promoting Economic Competitiveness While Safeguarding Privacy, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties in Domestic Use of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (February 15, 2015), the Department and FAA will participate in the multi-stakeholder engagement process led by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) to assist in this process regarding privacy, accountability, and transparency issues concerning commercial and private UAS use in the NAS. We also note that state law and other legal protections for individual privacy may provide recourse for a person whose privacy may be affected through another person's use of a UAS.

The FAA conducted a privacy impact assessment (PIA) of this rule as required by section 522(a)(5) of division H of the FY 2005 Omnibus Appropriations Act, Public Law 108-447, 118 Stat. 3268 (Dec. 8, 2004) and section 208 of the E-Government Act of 2002, Public Law 107-347, 116 Stat. 2889 (Dec. 17, 2002). The assessment considers any impacts of the proposed rule on the privacy of information in an identifiable form. The FAA has determined that this proposed rule would impact the FAA's handling of personally identifiable information (PII). As part of the PIA that the FAA conducted as part of this rulemaking, the FAA analyzed the effect this impact might have on collecting, storing, and Start Printed Page 9553disseminating PII and examined and evaluated protections and alternative information handling processes in developing the proposed rule in order to mitigate potential privacy risks.

As proposed, the process for granting unmanned aircraft operator certificates with a small UAS rating would be brought in line with the process for granting traditional airman certificates. Thus, the privacy implications of this rule to the privacy of the information that would be collected, maintained, stored, and disseminated by the FAA in accordance with this rule are the same as the privacy implications of the FAA's current airman certification processes. These privacy impacts have been analyzed by the FAA in the following Privacy Impact Assessments for the following systems: Civil Aviation Registry Applications (AVS Registry); the Integrated Airman Certification and Ratings Application (IACRA); and Accident Incident Database. These Privacy Impact Assessments are available in the docket for this rulemaking and at http://www.dot.gov/individuals/privacy/privacy-impact-assessments#Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

B. Applicability

To integrate small UAS operations into the NAS, this proposed rule would create a new part in title 14 of the CFR: Part 107. Subject to the exceptions discussed below, proposed part 107 would prescribe the rules governing the registration, airman certification, and operation of civil small UAS within the United States. As mentioned previously, a small UAS is a UAS that uses an unmanned aircraft weighing less than 55 pounds. This proposed rule would allow non-recreational small UAS to operate in the NAS. The operations enabled by this proposed rule would include business, academic, and research and development flights, which are hampered by the current regulatory framework.

Under this proposal, the regulations of part 107, which are tailored to address the risks associated with small UAS operations, would apply to small UAS operations in place of certain existing FAA regulations that impede civil small UAS operations. Specifically, for small UAS operations, the requirements of proposed part 107 would generally replace the airworthiness provisions of part 21, the airman certification provisions of part 61, and the operating limitations of part 91.

However, proposed part 107 would not apply to all small UAS operations. For the reasons discussed below, proposed part 107 would not apply to: (1) Air carrier operations; (2) external load and towing operations; (3) international operations; (4) foreign-owned aircraft that are ineligible to be registered in the United States; (5) public aircraft; (6) certain model aircraft; and (7) moored balloons, kites, amateur rockets, and unmanned free balloons.

1. Air Carrier Operations

When someone is transporting persons or property by air for compensation, that person is considered an air carrier by statute and is required to obtain an air carrier operating certificate.[28] Because there is an expectation of safe transportation when payment is exchanged, air carriers are subject to more stringent regulations to mitigate the risks posed to persons or non-operator-owned property on the aircraft.

The FAA notes that some industries may desire to transport property via UAS.[29] Proposed part 107 would not prohibit this type of transportation so long as it is not done for compensation and the total weight of the aircraft, including the property, is less than 55 pounds. For example, research and development operations transporting property could be conducted under proposed part 107, as could operations by corporations transporting their own property within their business under the other provisions of this proposed rule.

The FAA seeks comment on whether UAS should be permitted to transport property for payment within the other proposed constraints of the rule, e.g., the ban on flights over uninvolved persons, the requirements for line of sight, and the intent to limit operations to a constrained area. The FAA also seeks comment on whether a special class or classes of air carrier certification should be developed for UAS operations.

2. External Load and Towing Operations

The FAA considered allowing small unmanned aircraft to conduct external-load operations and to tow other aircraft or objects. These operations involve a greater level of public risk due to the dynamic nature of external-load configurations and inherent risks associated with the flight characteristics of a load that is carried, or extends, outside the aircraft fuselage and may be jettisonable. These types of operations may also involve evaluation of the aircraft frame for safety performance impacts, which may require airworthiness certification.

Given the risks associated with external load and towing operations, the FAA cannot find that a certification is not required. However, the FAA invites comments, with supporting documentation, on whether external-load UAS operations and towing UAS operations should be permitted, whether they would require airworthiness certification, whether they would require higher levels of airman certification, whether they would require additional operational limitations, and on other relevant issues.

3. International Operations

At this time, the FAA also proposes to limit this rulemaking to small UAS operations conducted entirely within the United States. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) recognizes that:

The safe integration of UAS into non-segregated airspace will be a long-term activity with many stakeholders adding their expertise on such diverse topics as licensing and medical qualification of UAS crew, technologies for detect and avoid systems, frequency spectrum (including its protection from unintentional or unlawful interference), separation standards from other aircraft, and development of a robust regulatory framework.[30]

ICAO has further stated that “[u]nmanned aircraft . . . are, indeed aircraft; therefore existing [ICAO standards and recommended practices] SARPs apply to a very great extent. The complete integration of UAS at aerodromes and in the various airspace classes will, however, necessitate the development of UAS-specific SARPs to supplement those already existing.” [31] ICAO has begun to issue and amend SARPs to specifically address UAS operations. For example, the standard contained in paragraph 3.1.9 of Annex 2 (Rules of the Air) to the Convention on International Civil Aviation states that “A remotely piloted aircraft shall be operated in such a manner as to minimize hazards to persons, property or other aircraft and in accordance with the conditions specified in Appendix 4.” This appendix sets forth detailed conditions ICAO Member States must require of civil UAS operations for the ICAO Member State to comply with the Annex 2, paragraph 3.1.9 standard. ICAO standards in Annex 7 (Aircraft Nationality and Registration Marks) to the Convention also require remotely Start Printed Page 9554piloted aircraft to “carry an identification plate inscribed with at least its nationality or common mark and registration mark” and be “made of fireproof metal or other fireproof material of suitable physical properties.” For remotely piloted aircraft, this identification plate must be “secured in a prominent position near the main entrance or compartment or affixed conspicuously to the exterior of the aircraft if there is no main entrance or compartment.”

While we embrace the basic principle that UAS operations should minimize hazards to persons, property or other aircraft, we believe that it is possible to achieve this goal with respect to certain small UAS operations in a much less restrictive manner than current ICAO standards require. Accordingly, the FAA proposes, for the time being, to limit the applicability of proposed part 107 to small UAS operations that are conducted entirely within the United States. The FAA envisions that international operations would be dealt with in a future FAA rulemaking. The FAA believes that the experience that the FAA will gain with UAS operations under this rule will assist with future rulemakings. The FAA also anticipates that ICAO will continue to revise and more fully develop its framework for UAS operations to better reflect the diversity of UAS operations and types of UAS and to distinguish the appropriate levels of regulation in light of those differences.

The FAA notes that under Presidential Proclamation 5928, the territorial sea of the United States, and consequently its territorial airspace, extends to 12 nautical miles from the baselines of the United States determined in accordance with international law. Thus, UAS operating in the airspace above the U.S. territorial sea would be operating within the United States for the purposes of this proposed rule.

The FAA also emphasizes that proposed part 107 would not prohibit small UAS operators from operating in international airspace or in other countries; however, the proposed rule also would not provide authorization for such operations. UAS operations that do not take place entirely within the United States would need to obtain all necessary authorizations from the FAA and the relevant foreign authorities outside of the part 107 framework, as that framework would not apply to operations that do not take place entirely within the United States. It is important to note that Article 8 of the Convention on International Civil Aviation, to which the U.S. is a party, provides:

No aircraft capable of being flown without a pilot shall be flown without a pilot over the territory of a contracting State without special authorization by that State and in accordance with the terms of such authorization. Each contracting State undertakes to insure that the flight of such aircraft without a pilot in regions open to civil aircraft shall be so controlled as to obviate danger to civil aircraft.

Accordingly, UAS operations in foreign countries may not take place without the required authorizations and permission of that country.

4. Foreign-Owned Aircraft That Are Ineligible for U.S. Registration

The FAA proposes to limit the scope of this rulemaking to U.S.-registered aircraft. Under 49 U.S.C. 44103 and 14 CFR 47.3, an aircraft can be registered in the United States only if it is not registered under the laws of a foreign country and meets one of the following ownership criteria:

- The aircraft is owned by a citizen of the United States;

- The aircraft is owned by a permanent resident of the United States;

- The aircraft is owned by a corporation that is not a citizen of the United States, but that is organized and doing business under U.S. Federal or state law and the aircraft is based and primarily used in the United States; or

- The aircraft is owned by the United States government or a state or local governmental entity.

An aircraft that does not satisfy the above criteria is typically owned by a foreign person or entity and is subject to special operating rules.[32] As previously noted, the ICAO framework for international UAS operations is at a relatively early stage in its development. Accordingly, proposed part 107 would only apply to small unmanned aircraft that meet the criteria specified in § 47.3, which must be satisfied in order for an aircraft to be eligible for U.S. registration. The FAA notes existing U.S. international trade obligations do permit certain kinds of operations, known as specialty air services. Specialty air services are generally defined as any specialized commercial operation using an aircraft whose primary purpose is not the transportation of goods or passengers, including but not limited to aerial mapping, aerial surveying, aerial photography, forest fire management, firefighting, aerial advertising, glider towing, parachute jumping, aerial construction, helilogging, aerial sightseeing, flight training, aerial inspection and surveillance, and aerial spraying services. The FAA will consult with the Secretary to determine the process through which it might permit foreign-owned small unmanned aircraft to operate in the United States. The FAA invites comments on the inclusion of foreign-registered small unmanned aircraft in this new framework.

As provided by 49 U.S.C. 40105(b)(1)(A), the FAA Administrator must carry out his responsibilities under Part A (Air Commerce and Safety) of title 49, United States Code, consistently with the obligations of the U.S. Government under international agreements. The FAA invites comments regarding whether the proposed rule needs to be modified to ensure that it is consistent with any relevant obligations of the United States under international agreements.

5. Public Aircraft Operations

This proposed rule would also not apply to public aircraft operations with small UAS that are not operated as civil aircraft. This is because public aircraft operations, such as those conducted by the Department of Defense, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, are not required to comply with civil airworthiness or airman certification requirements to conduct operations. However, these operations are subject to the airspace and air-traffic rules of part 91, which include the “see and avoid” requirement of § 91.113(b). Because unmanned aircraft operations currently are incapable of complying with § 91.113(b), the FAA has required public aircraft operations that use unmanned aircraft to obtain an FAA-issued Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) providing the public aircraft operation with a waiver/deviation from the “see and avoid” requirement of § 91.113(b).

The existing COA system has been in place for over eight years, and has not caused any significant human injuries or other significant adverse safety impacts.[33] Accordingly, this proposed rule would not abolish the COA system. However, this proposed rule would provide public aircraft operations with greater flexibility by giving them the option to declare an operation to be a civil operation and comply with the provisions of proposed part 107 instead Start Printed Page 9555of seeking a COA from the FAA. Because proposed part 107 would address the risks associated with small UAS operations, there would be no adverse safety effects from allowing public aircraft operations to be voluntarily conducted under proposed part 107.[34]

6. Model Aircraft

Proposed part 107 would not apply to model aircraft that satisfy all of the criteria specified in section 336 of Public Law 112-95. Section 336 of Public Law 112-95 defines a model aircraft as an “unmanned aircraft that is—(1) capable of sustained flight in the atmosphere; (2) flown within visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft; and (3) flown for hobby or recreational purposes.” [35] Because section 336 of Public Law 112-95 defines a model aircraft as an “unmanned aircraft,” a model aircraft that weighs less than 55 pounds would fall into the definition of small UAS under this rule.

However, Public Law 112-95 specifically prohibits the FAA from promulgating rules regarding model aircraft that meet all of the following statutory criteria: [36]

- The aircraft is flown strictly for hobby or recreational use;

- The aircraft is operated in accordance with a community-based set of safety guidelines and within the programming of a nationwide community-based organization;

- The aircraft is limited to not more than 55 pounds unless otherwise certified through a design, construction, inspection, flight test, and operational safety program administered by a community-based organization;

- The aircraft is operated in a manner that does not interfere with and gives way to any manned aircraft; and

- When flown within 5 miles of an airport, the operator of the aircraft provides the airport operator and the airport air traffic control tower (when an air traffic facility is located at the airport) with prior notice of the operation.

Because of the statutory prohibition on FAA rulemaking regarding model aircraft that meet the above criteria, model aircraft meeting these criteria would not be subject to the provisions of proposed part 107. Likewise, operators of model aircraft excepted from part 107 by the statute would not need to hold an unmanned aircraft operator's certificate with a small UAS rating. However, the FAA emphasizes that because the prohibition on rulemaking in section 336 of Public Law 112-95 is limited to model aircraft that meet all of the above statutory criteria, model aircraft weighing less than 55 pounds that fail to meet all of the statutory criteria would be subject to proposed part 107.

In addition, although Public Law 112-95 excepted certain model aircraft from FAA rulemaking, it specifically states that the law's exception does not limit the Administrator's authority to pursue enforcement action against those model aircraft operators that “endanger the safety of the national airspace system.” [37] This proposed rule would codify the FAA's enforcement authority in part 101 by prohibiting model aircraft operators from endangering the safety of the NAS.

The FAA also notes that it recently issued an interpretive rule explaining the provisions of section 336 and concluding that “Congress intended for the FAA to be able to rely on a range of our existing regulations to protect users of the airspace and people and property on the ground.”[38] In this interpretive rule, the FAA gave examples of existing regulations the violation of which could subject model aircraft to enforcement action. Those regulations include:

- Prohibitions on careless or reckless operation and dropping objects so as to create a hazard to persons or property (14 CFR 91.13 and 91.15);

- Right-of-way rules for converging aircraft (14 CFR 91.113);

- Rules governing operations in designated airspace (14 CFR part 73 and §§ 91.126 through 91.135); and

- Rules relating to operations in areas covered by temporary flight restrictions and notices to airmen (NOTAMs) (14 CFR 91.137 through 91.145).[39]

The FAA notes that the above list is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all existing regulations that apply to model aircraft meeting the statutory criteria of Public Law 112-95, section 336. Rather, as explained in the interpretive rule, “[t]he FAA anticipates that the cited regulations are the ones that would most commonly apply to model aircraft operations.” [40]

7. Moored Balloons, Kites, Amateur Rockets, and Unmanned Free Balloons

Lastly, proposed part 107 would not apply to moored balloons, kites, amateur rockets, and unmanned free balloons. These types of aircraft currently are regulated by the provisions of 14 CFR part 101. Because these aircraft are already incorporated into the NAS through part 101 and because the safety risks associated with these specific aircraft are already mitigated by the regulations of part 101, there is no need to make these aircraft subject to the provisions of proposed part 107.

C. Definitions

Proposed part 107 would create a new set of definitions to address the unique aspects of a small UAS. Those proposed definitions are as follows.

1. Control Station

Proposed part 107 would define a “control station” as an interface used by the operator to control the flight path of the small unmanned aircraft. In a manned aircraft, the interface used by the pilot to control the flight path of the aircraft is a part of the aircraft and is typically located inside the aircraft flight deck. Conversely, the interface used to control the flight path of a small unmanned aircraft is typically physically separated from the aircraft and remains on the ground during aircraft flight. Defining the concept of a control station would clarify the interface that is considered part of the small UAS under this regulation.

2. Corrective Lenses

Proposed part 107 would also define “corrective lenses” as spectacles or contact lenses. As discussed in the Operating Rules section of this preamble, this proposed rule would require the operator and/or visual observer to have visual line of sight of the small unmanned aircraft with vision that is not enhanced by any device other than corrective lenses. This is because spectacles and contact lenses do not restrict a user's peripheral vision while other vision-enhancing devices may restrict that vision. Because peripheral vision is necessary in order for the operator and/or visual observer to be able to see and avoid other air traffic in the NAS, this proposed rule would limit the circumstances in which vision-enhancing devices other than spectacles or contact lenses may be used.Start Printed Page 9556

3. Operator and Visual Observer

Because of the unique nature of small UAS operations, this proposed rule would create two new crewmember positions: The operator and the visual observer. These positions are discussed further in section III.D.1 of this preamble.

4. Small Unmanned Aircraft

Public Law 112-95 defines a “small unmanned aircraft” as “an unmanned aircraft weighing less than 55 pounds.” [41] This statutory definition of small unmanned aircraft does not specify whether the 55-pound weight limit refers to the total weight of the aircraft at the time of takeoff (which would encompass the weight of the aircraft and any payload on board), or simply the weight of an empty aircraft.